This policy brief is based on a recently published paper: Otrachshenko, V., and O. Popova (2026). Environment vs. economic growth: Do environmental preferences translate into support for Green parties? Ecological Economics 239, 108779, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2025.108779. The views expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the organizations with which the authors are affiliated.

Abstract

This policy brief summarizes key findings from a forthcoming paper by Otrachshenko and Popova (2026), which shows that individuals who prioritize environmental protection over economic growth are more likely to vote for Green parties globally. However, this support is not uniform and is strongly influenced by individual economic security. Economically disadvantaged individuals, including those with lower education, lower income, and rural residents, show less pronounced support for Green parties, even when they hold strong environmental preferences. This highlights a crucial insight: To gain public support for environmental policies and ensure their long-term feasibility, particularly among economically vulnerable populations, it is essential to balance environmental protection and economic security measures.

Global environmental concerns are growing, with a substantial majority of the population demanding stronger governmental action on climate change (UNDP, 2024). At the same time, environmental policies frequently encounter legislative and public opposition, often rooted in their perceived economic costs to both businesses and households (Otrachshenko and Popova, 2026). Historically, Green parties have struggled to achieve stable electoral success and widespread policy influence, suggesting that environmental protection is frequently viewed as a “secondary policy issue,” meaning support may be more robust during periods of economic prosperity (e.g., McAlexander and Urpelainen, 2020). As a result, implementing environmental policies consistently becomes a challenging yet urgent task.

The impacts of natural disasters and extreme weather events are becoming increasingly severe globally, making governmental action on climate change an integral part of economic policymaking (Botzen et al., 2019; IPCC, 2023). This requires stable public support for environmental policies and Green parties that promote these policies. At the same time, the costs of climate change prevention and mitigation borne by both businesses and households grow, deterring potential voters from supporting Green parties and environmental actions (Otrachshenko and Popova, 2026).

Recent survey evidence suggests that while European citizens support governmental action on climate change, they are less likely to perceive themselves as personally accountable for such action. Specifically, more than 70% of respondents surveyed in 8 European countries (Czech Republic, Germany, France, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the UK) think that the national governments, the European Union, and large international firms should be responsible for climate action, but only 30 to 50% feel personally responsible, with the highest personal responsibility being in Germany, Sweden, and the UK, and the lowest in the Czech Republic and Poland (Eichhorn et al., 2020). Similarly, about 45% are not willing to pay higher taxes, and about 35% are willing to pay only a small amount (one hour of monthly salary) for climate action (Eichhorn et al., 2020). In other words, by voting for Green parties, individuals indirectly express their willingness to pay for costly environmental policies (Otrachshenko and Popova, 2026). Therefore, a deeper understanding of the factors driving public support for environmental policies is essential for their effective implementation.

In Otrachshenko and Popova (2026), we utilize individual-level survey data from 60 countries between 2017 and 2022, encompassing approximately 60,000 individuals globally, to investigate the key drivers of public support for Green parties and the environmental policies they advocate.

We demonstrate that individual priorities for environmental protection over economic growth affect support for Green parties. Individuals who explicitly prioritize environmental protection over economic growth are 3.1 percentage points more likely to vote for Green parties compared to those who prioritize economic growth. This highlights a direct, quantifiable trade-off between environment and economic growth in voter preferences. The magnitude of this effect is non-negligible. For instance, the effect of environmental preferences in voting for Green parties is approximately three times greater than the effect of a higher education and twice as high as the effect of individual income on the likelihood of voting for Green parties1. Even more strikingly, parties that balance environmental protection with economic concerns (“pro-Green” parties) are likely to gain significantly more support than purely “Green” parties. We show that environmentally inclined individuals are more likely to vote for pro-Green parties by 8.5 percentage points, compared to those who prefer economic growth. This impact is almost three times greater than the effect of preferences for environmental protection on voting for Green parties.

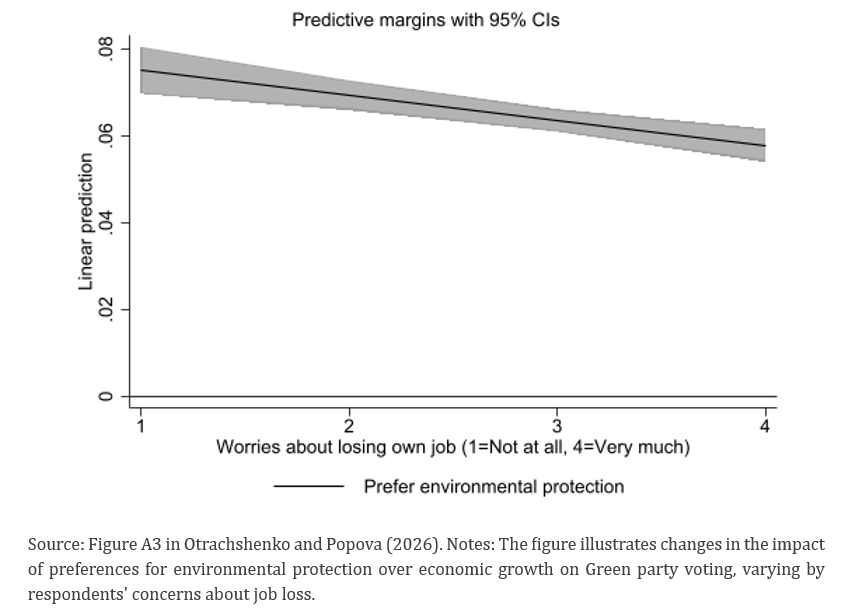

Another finding is that the support for Green parties is not uniform and is heavily influenced by individual economic security. Economically disadvantaged individuals, including those with lower education, lower income, and rural residents, show less pronounced support for Green parties, even when they hold strong environmental preferences. In addition, economic insecurity can be measured by individual worries about losing one’s own job. As shown in Figure 1, with the higher worries about one’s own job loss, the impact of environmental preferences on voting for Green parties is diminishing.

Figure 1. Worries about a job loss reduce the impact of environmental preferences on the support for Green parties

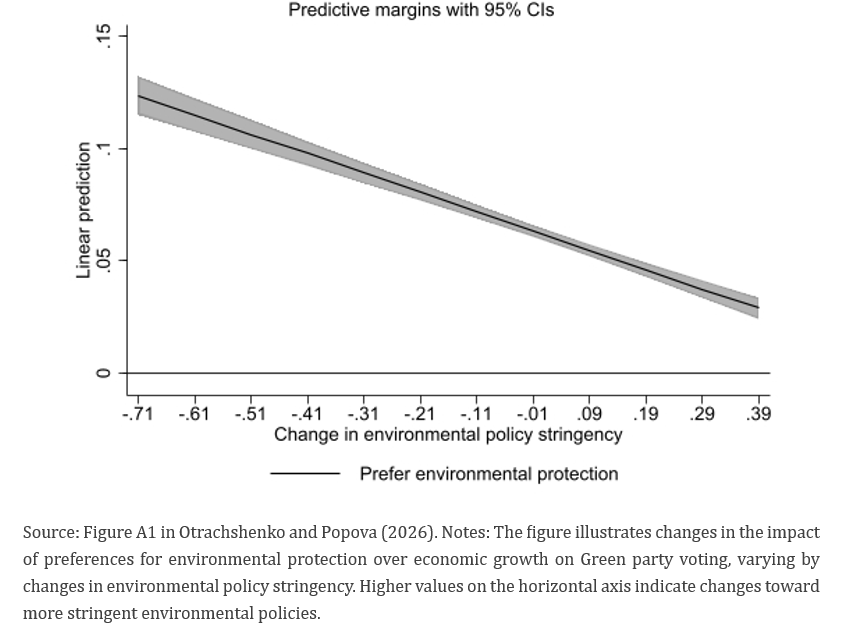

Individual economic insecurity can be attributed to concerns about increased financial contributions and taxes associated with implementing climate change mitigation measures. Indeed, the full-scale introduction of the Emission Trading System II (ETS2) by the European Union from 2027 is expected to boost household energy expenses by 30-40% (Bloomberg, 2025). As shown in Figure 2, strengthening environmental policy regulations also reduces the impact of environmental preferences on voting for Green parties.

Figure 2. Environmental policy stringency reduces the impact of environmental preferences on the support for Green parties

In Otrachshenko and Popova (2026), we show that the salience of environmental changes and the income losses they bring also play a role. By exacerbating economic insecurity concerns, country-level GDP losses from natural disasters diminish the impact of environmental preferences on voting for Green parties, particularly among occupations more exposed to nature, such as farmers and farm workers. At the same time, we find that stronger social safety nets in a country may help address economic insecurity concerns and reinforce the role of individual priorities for environmental protection in the Green parties’ support.

These findings emphasize that addressing the economic concerns of vulnerable population groups is key to gaining broader public support for environmental policies, especially in developing countries that are more vulnerable to climate change. In addition, raising environmental awareness among the population is important for maintaining strong public support for environmental policies.

To gain public support for environmental policies and ensure their long-term feasibility, particularly among economically vulnerable populations, an integrated economic approach is essential. It implies several important policy measures that need to be considered:

Bloomberg, 2025. Europe’s new Emissions Trading System expected to have world’s highest carbon price in 2030 at €149, BloombergNEF forecast reveals, March 6. Available at: https://about.bnef.com/insights/commodities/europes-new-emissions-trading-system-expected-to-have-worlds-highest-carbon-price-in-2030-at-e149-bloombergnef-forecast-reveals/ (last accessed on September 3, 2025).

Botzen, W.J.W., Deschenes, O., and M. Sanders, 2019. The economic impacts of natural disasters: A review of models and empirical studies. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 13(2), 167-188. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rez004.

Eichhorn, J., Molthof, L., and S. Nicke, 2020. From climate change awareness to climate crisis action: Public perceptions in Europe and the United States. Open Society European Policy Institute. Available at: http://wordpress.dpart.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Comparative_report.pdf (last accessed on August 31, 2025).

IPCC, 2023. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 184 pp. DOI: https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.

McAlexander, R.J., and J. Urpelainen, 2020. Elections and policy responsiveness: evidence from environmental voting in the U.S. Congress. Review of Policy Research 37(1), 39–63. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12368.

Otrachshenko, V., and O. Popova, 2026. Environment vs. economic growth: Do environmental preferences translate into support for Green parties? Ecological Economics 239, 108779. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2025.108779.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2024. The People’s Climate Vote 2024. Available at: https://www.undp.org/publications/peoples-climate-vote-2024 (last accessed on July 30, 2024).

The calculation is based on Table A2 in Otrachshenko and Popova (2026).