This policy brief is based on IFC Bulletin no 63 on “Addressing climate change data needs: the central banks’ contribution”. The views expressed in this brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bank of France, the BIS, the CBRT, the Deutsche Bundesbank, the ECB, the IFC or the OECD.

Abstract

Improving climate risk data has become an acknowledged imperative, including for central banks, which are increasingly integrating climate considerations into their policymaking frameworks. While significant progress has been made through national and international initiatives, challenges persist in terms of data availability, reliability and comparability, in particular for the development of forward-looking indicators for physical and transition risks. Central banks, as both producers and users of statistics, can play a pivotal role in addressing these challenges. By fostering global collaboration, promoting harmonised methodologies, and leveraging technological innovation, they can help bridge critical data gaps and enhance climate resilience strategies. This paper (and the corresponding IFC Bulletin (Nefzi et al 2025)) highlights the key data challenges faced, reviews central banks’ contributions to national and international efforts, and explores the potential of emerging data sources and tools to better inform climate-related policymaking.

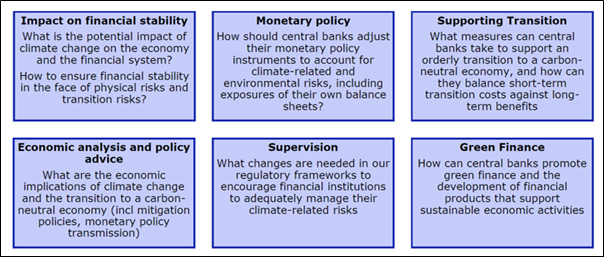

Central banks increasingly rely on robust evidence to assess climate-related risks as part of their public mandates. Climate change is expected to impact their monetary and financial stability goals, as well as the microprudential supervision of financial institutions for those central banks tasked with this specific role. Additionally, many central banks, depending on their mandate, are actively supporting green finance to mitigate climate change (Graph 1).

Climate risks may significantly affect monetary policy by disrupting supply chains, reducing output, and increasing production costs, which can lead to inflationary pressures. Extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods, can cause transitory price increases, while the transition to a low-carbon economy may result in structural price shifts due to factors like carbon pricing and regulatory changes. These dynamics will challenge central banks’ ability to maintain price stability, potentially requiring adjustments to monetary policy frameworks and operations, such as asset purchase programmes (NGFS (2021)).

Climate risks may also pose issues in terms of financial stability. Physical risks, such as extreme weather, can lead to asset devaluations, insurance losses, and borrower defaults, particularly in sectors like real estate and agriculture. Transition risks, such as shifts in policies or technology, may increase stranded assets in carbon-intensive industries, destabilising financial markets. To address these risks, central banks are integrating climate risk analysis into their macroprudential and microprudential frameworks, using scenario analyses and monitoring vulnerabilities (ECB (2023) and Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2024)). Enhanced climate-related disclosure requirements are also essential to improve information quality for authorities and stakeholders.

Central banks are supporting green finance by improving data availability and tracking investments in environmentally-friendly activities. Granular data from security-by-security (SBS) databases are being used to identify green bonds and sustainability-linked instruments, helping policymakers understand the scale and direction of green finance. Efforts are also under way to standardise methodologies for compiling green finance statistics. For example, the ECB uses SBS databases to measure green equity and debt instruments, revealing a rapid increase in the issuance of green securities and the importance of relying on external certification for data assurance (Fusero et al (2025)).

Graph 1. Central banks’ activities related to climate change

Source: Fortanier (2025).

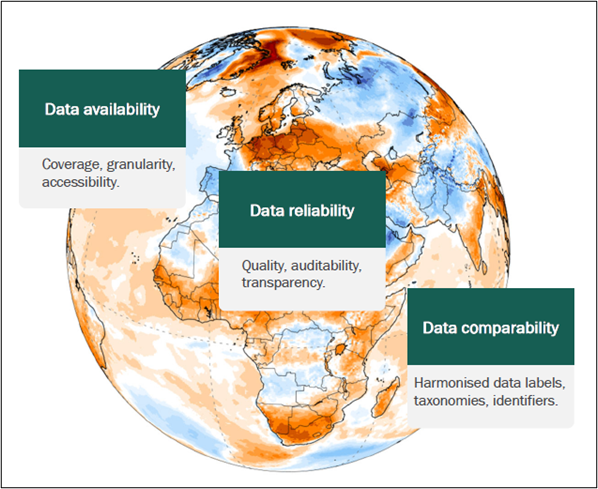

Addressing climate risks requires data at various aggregation levels to meet diverse stakeholder needs. At the micro level, companies are increasingly required to disclose climate-related reports to measure the carbon content of economic output (IFC (2024)) as well as for supervisory purposes, such as stress tests. At the macro and global level, comprehensive, publicly available data are needed for various purposes, for example on country emissions. However, three key data challenges persist: data availability, reliability and comparability (Graph 2).

Significant data gaps exist, particularly for non-listed financial instruments, loans and private equity, especially in emerging markets. Even for well-covered instruments like listed corporate debt, data availability is uneven, with better coverage in Europe and North America compared to other regions. Addressing these gaps requires enhanced corporate disclosure requirements, capacity-building efforts and leveraging emerging technologies like geospatial data and artificial intelligence (AI). For instance, satellite data are already being used to assess physical risks and to monitor methane emissions.

Reliable data are critical for meaningful policy action and limiting greenwashing. However, transparency and credibility of methodologies are often lacking. For example, carbon offset markets suffer from weak data quality due to underdeveloped methodological concepts. Clear standards, guidance, and certification are therefore needed to ensure data reliability.

Comparing climate-related data across jurisdictions and sectors is challenging due to differing methodologies, assumptions and metrics. For instance, climate ratings for the same companies vary widely across providers due to differences in emissions coverage, timeframes and metrics. Greater transparency and international convergence on taxonomies and disclosure standards are essential to improve comparability.

Graph 2. Addressing climate-related information needs – main data challenges

Source: IFC Bulletin no 63.

Physical risk measurement would ideally require granular, asset-level data, but such information is often unavailable or difficult to allocate to specific asset owners. Current analyses thus have to rely on a mix of micro and aggregate data, which limits their scope. Transition risk analysis is equally challenging due to disparities in data availability and methodologies, complicating the development of forward-looking metrics. These gaps can significantly hinder central banks and supervisors in estimating the financial impact of transition risks.

Combining physical and transition risks over extended timeframes remains a significant obstacle for developing comprehensive scenario analyses. This is critical for simulating short- and long-term impacts on financial institutions and improving climate risk assessments (eg Schmieder et al (2025)).

Central banks are playing an increasingly critical role in addressing climate risk data gaps, leveraging their unique position as both producers of statistics and users of robust, reliable evidence. They are in particular taking a multifaceted approach to improve the availability, reliability and comparability of climate risk data, thereby catering to their own and others policy needs.

Central banks have already initiated numerous activities to tackle climate data issues in supporting their key tasks:

Looking ahead, central banks appear well-positioned to advance global efforts to close climate risk data gaps, either on their own initiative or together with other interested stakeholders:

1. Compiling and enhancing climate data

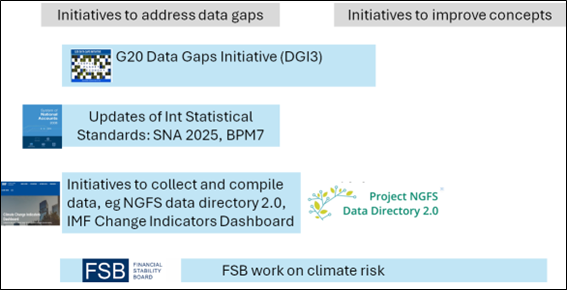

Central banks can consolidate and make sense of the growing volume of climate-related data from diverse sources and formats. They may also develop analytical indicators, particularly in their oversight roles, to better assess risks and opportunities. For example, they have been fostering coordinated data work on climate risk within national ecosystems, collaborating closely with statistical offices to improve data collection and analysis (eg in the context of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) work, see Graph 3).

2. Leveraging technological innovation to compile data

Emerging technologies, such as geospatial data and AI/machine learning, are being utilised by central banks and other stakeholders to bridge data gaps. For example:

3. Supporting green finance with granular data

Central banks are using tools like SBS databases to identify and track green financial instruments, such as green bonds and sustainability-linked bonds. Efforts are also under way to better measure green equity and assess the environmental impact of global supply chains, particularly through foreign direct investment (FDI).

4. Participating in international initiatives

Central banks are actively contributing to global efforts, such as the G20 Data Gaps Initiative (DGI – Graph 3), to improve climate-related data. These initiatives focus on:

5. Promoting global collaboration

Central banks are fostering cooperation among key stakeholders, including multilateral institutions, financial regulators, finance ministries, academia and the private sector. This collaboration is essential to develop interoperable taxonomies, harmonised sustainability disclosure standards and innovative solutions to tackle climate data challenges.

6. Facilitating information sharing

Enhanced sharing of data, methodologies and frameworks is essential for accurately assessing the environmental footprint of economic activities. Central banks are encouraging the exchange of experiences and best practices to address this global issue, ensuring that stakeholders benefit from collective knowledge and insights.

7. Developing statistical strategies

Central banks are working to bridge data gaps by developing clear and ambitious statistical strategies. This includes identifying the most relevant indicators, creating technical solutions and advancing international collaborations to improve data collection. To this end, the Irving Fisher Committee on Central Bank Statistics (IFC) of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) organised a dedicated workshop on “Addressing climate change data needs: the global debate and central banks’ contribution” with the Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye, the Bank of France and Deutsche Bundesbank in May 2024.1

Graph 3. Key climate data-related initiatives at the global level

Source: Harutyunyan et al (2025).

In sum, central banks have emerged as key players in addressing climate risk data gaps. Through their efforts to compile and enhance data, foster international collaboration, leverage technology and promote green finance, they are helping to build a more resilient global financial system. By continuing to work with other relevant stakeholders and adopting innovative approaches, they can significantly contribute to bridging critical information gaps and supporting the transition to a sustainable economy.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2024): Pilot climate scenario analysis (CSA) exercise: summary of participants’ risk-management practices and estimates, May.

European Central Bank (ECB) (2023): “Climate change considerations in monetary policy implementation”, Monetary Dialogue Papers, November.

Fortanier, F (2025): “Central banks and climate risk initiatives”, IFC Bulletin, no 63, March.

Fusero, F, J Kleibl and D Theleriti (2025): “Compiling climate finance statistics from security-by-security data”, IFC Bulletin, no 63, March.

Harutyunyan, A, P Hurree-Gobin, M Kutlukaya and F Fareed (2025): “Going green in finance: bridging data gaps for enhanced financial risk and opportunities assessment”, IFC Bulletin, no 63, March.

Irving Fisher Committee on Central Bank Statistics (IFC) (2024)): “Empowering carbon accounting: from data to action”, IFC Report, no 16, October.

Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) (2021): Adapting central bank operations to a hotter world.

Schmieder, C, A Srivastav and M Petkov (2025): “A framework for macro-financial analysis of climate risks”, IFC Bulletin, no 63, March.

The workshop built upon previous IFC work in this area (IFC (2021)); the proceedings were published in IFC Bulletin no 63.