This policy brief is based on the article “Rethinking currency internationalisation: offshore money creation and the EU’s monetary governance” in the Journal of European Public Policy.

Abstract

Currency internationalisation has been one of International Political Economy’s (IPE) “perennial questions” (Germain and Schwartz 2014, 196). In this policy brief, we introduce a new account of currency internationalisation that emphasises the crucial role of the state in successful internationalisation, in particular for fostering the offshore creation of private credit money. We use this account to better understand the limited international role of the euro to date. We also identify three neglected modalities for promoting EU internationalisation: endorsing cross-border value chains through offshore euro payment chains, more ex-ante clarity on access to euro swap lines for states with large reliance on offshore euros, as well as improving the safe asset status of euro-denominated public debt.

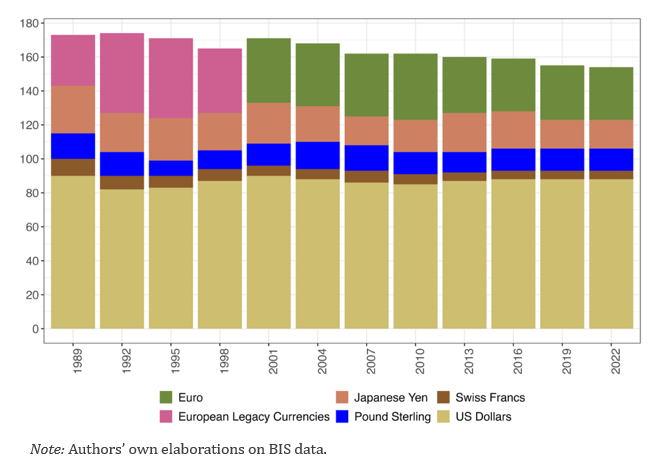

Internationalisation of the euro has for decades eluded EU policymakers. In spite of more than 30 years of European debates to establish the euro as a systemic rival to the U.S. dollar, the euro has only made marginal progress beyond what the European currencies that preceded the euro had already achieved (see Figure 1). Efforts to actively promote the international euro remain virtually non-existent. In fact, until 2018, the ECB did not treat internationalisation as a genuine objective. As the ECB’s first President Wim Duisenberg famously argued, the ECB should accept the international role of the euro as it develops as a result of market forces. To the extent that the Eurosystem is successful in meeting its mandate and maintaining price stability, it will also automatically foster the use of the euro as an international currency (Duisenberg 1999).

This remained the ECB’s stated policy until 2018, when the first Trump administration triggered a flurry of reports and good intentions (Juncker 2018; EC 2019; 2021).

Figure 1. Turnover of over-the-counter foreign exchange instruments for selected instruments, 1989–2022 (percentage of total)

Since then, the ECB has acknowledged the importance of the euro’s international role but remains reluctant to promote it: the international role of the euro is primarily supported by a deeper and more complete Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), including advancing the capital markets union, in the context of the pursuit of sound economic policies in the euro area. The Eurosystem supports these policies and emphasises the need for further efforts to complete EMU (ECB 2024, 2).

Taking a market-led approach, EU policymakers continue to ignore what is at the core of decades of IPE scholarship: the role of the state in “monetary governance”, understood as the combined practices through which political actors promote the issuance of monetary instruments in their currency.

This policy brief introduces a new conceptual framework for currency internationalisation that emphasizes the credit nature of money and the crucial role of offshore monetary governance. We use this framework to develop a novel explanation of the euro’s failure to internationalise and to highlight three neglected areas of offshore monetary governance:

In each case, we argue that the EU has failed to incentivise, and sometimes even discouraged, the expansion of offshore euro creation and thus undermined the objective of euro internationalisation. European policymakers’ deference to the decisions of firms, investors, and other states to determine the international status of the euro neglects the vital role of monetary authorities in promoting their currencies’ international use, as evidenced by the Fed’s long-standing backing for USD internationalisation (Murau, Pape, and Pforr 2022; Bateman and van ’t Klooster 2024). Unless the EU develops a serious strategy for offshore monetary governance, the euro is likely to remain subordinate to the U.S. dollar and subject to the whims of the incumbent U.S. president.

From a credit theory perspective, contemporary money is debt instruments (e.g. bank notes and bank deposits) within a complex global system of interlocking balance sheets. We distinguish three categories of monetary instruments, each issued on a specified balance sheet:

Moneyness is a matter of degree. It depends on the debt retaining a stable one-to-one value for its currency (‘trading at par’) and usability for payments denominated in that currency.

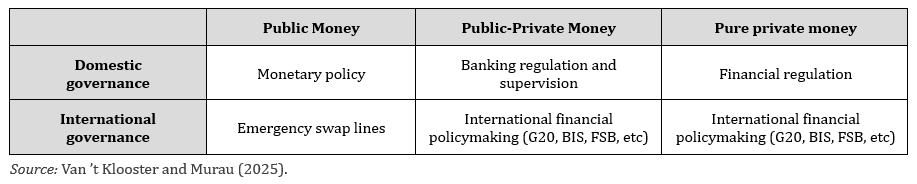

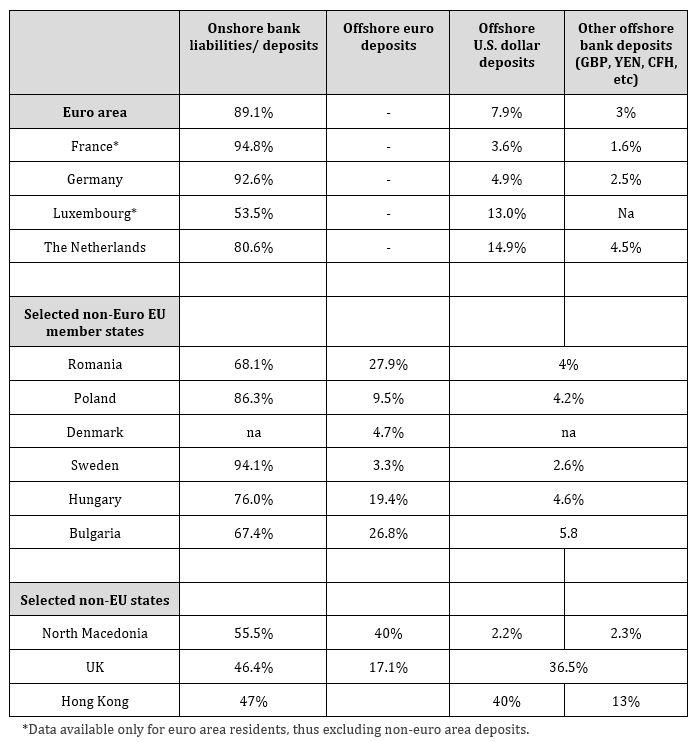

Since money creation is nothing more than issuing high-quality debt denominated in a specific unit of account, banks can issue such debt in foreign jurisdictions (Murau and van ’t Klooster 2023). Money can be issued “onshore” in the jurisdiction that issues the currency, as when a U.S. dollar deposit is issued inside the United States. Offshore money is issued in one jurisdiction but denominated in another jurisdiction’s unit of account. For instance, around 9.5% of deposits issued by the Polish banking system are denominated in euros and another 4.2% are denominated in U.S. dollars or other currencies. Offshore money creation constitutes a complex challenge for monetary governance because it falls between two jurisdictions: the one where the institution issuing it is domiciled and the jurisdiction of the international currency. Table 1 illustrates the domestic (onshore) and international (offshore) levels of monetary governance. These international fora all bestow geopolitical power on the U.S. as the issuer of the global currency.

Table 1. Domestic and international monetary governance

Table 2. Offshore bank deposits in selected jurisdictions (2023 Q4)

Source: Van ’t Klooster and Murau (2025); for euro area countries, the deposits are calculated as a ratio of the sum of deposits of MFIs excluding the ESCB in the selected country vis-à-vis euro area and non-euro area MFIs and non-MFIs denominated in euro to the same sum in all currencies.1

Taking offshore credit money seriously adds an important piece to the puzzle of why the EU has failed to internationalise the euro (Mundell 1961; 2002; Cohen 2011; McNamara 2008; Germain and Schwartz 2014; Eichengreen, Mehl, and Chiţu 2017). We highlight three neglected areas of offshore monetary governance. We argue that in each case, the EU’s actions have failed to incentivise, and even discouraged, the expansion of offshore euro creation and thus undermined the objective of euro internationalisation.

Creation of offshore euros in cross-border value chains

A crucial factor for currency internationalisation is the use of a given currency in cross-border value chains, which determines the need for the creation of offshore money denominated in this currency (Shin 2023): “the supply chain is a payment chain in reverse” (Pozsar and Sweeney 2020). For example, a Spanish importer of oil from Saudi Arabia could ask for a USD-denominated loan at a German bank in London, after which the Spanish firm will receive offshore U.S. dollar deposits which it can pay the Saudi exporter. The Saudi exporter may retain the payment on a U.S. dollar deposit issued by a Japanese bank in London or pay down a dollar denominated bond issued there (cf. He and McCauley 2012). Only at the Spanish pump does the oil get a price tag in euro. The current dominant role of the U.S. dollar in cross-border value chains rests on an international monetary order in which U.S. dollars can be created offshore, thereby facilitating an expansion of trade.

This structure of financial globalization is the result of at least 80 years of purposeful U.S. policy to establish U.S. dollars as the unit of account for trade in key global commodities, most notably in oil. While discussions emerged after the introduction of the euro that the new currency could increasingly be used as an alternative to the U.S. dollar in the global oil trade, no supportive measures materialised. As the global trading system has been rocked by the Trump administration’s tarriff policies and talk of further weaponisation of the U.S. dollar, the EU has a window of opportunity to promote the use of offshore euros in value chains it shares with trade partners in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, for example for clean energy. This could be coordinated with monetary measures to increase the safety of offshore euros trading partners.

International lender of last resort facilities for offshore euros

Successful currency internationalisation requires appropriately defined liquidity backstops to approximate the conditions for offshore money to those of onshore money. Like onshore banks, institutions that issue offshore money are vulnerable to bank runs. No jurisdiction will want extensive creation of euro denominated offshore money without ex ante guarantees for adequate swap lines.

The crucial role of backstops in an inherently unstable system of global offshore credit can be seen in the provision of swap lines to partner central banks by the Federal Reserve during the 2007-2009 Financial Crisis (McDowell 2012; 2016) and more recently during the COVID-19 Crisis in March 2020. The now institutionalised C6 swap network allows the ECB, the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, and the Swiss Central Bank to borrow an unlimited amount of U.S. dollars from the Fed while using their domestic currency as collateral, which they can create at will, while nine additional central banks have limited swap lines.

Compared to the U.S., the Eurosystem has been much less generous in providing international lender of last resort facilities to non-euro area countries, which operate on the use of offshore euro deposits (Vallée 2010; Tooze 2018; Spielberger 2023). The ECB could promote the euro offshore by making its lender of last resort facilities more predictable and transparent through extending its collateral framework to allow central banks with formal swap line agreements to more easily provide quality collateral (for example, foreign currency collateral).

Provision of euro-denominated safe assets to promote offshore euro creation

“Safe assets” are debt instruments that can be reasonably expected to keep their value during adverse systemic events (Caballero, Farhi, and Gourinchas 2017). Safe assets facilitate offshore money creation by enabling the creation of repos, stablecoins and other money-like claims issued against collateral. Safe assets also function as a secondary reserve abroad, complementing international lender of last resort facilities. US Treasuries are seen as the quintessential safe asset in the contemporary global financial system, as they are backed by the Fed and can be widely traded on repo markets, allowing non-US financial market participants to hold USD-denominated instruments abroad, while being able to convert them into deposits or reserves on short notice.

The ECB has repeatedly failed to back other European treasury securities, with the eligibility of public debt as collateral for its monetary policy operations being conditional on a sufficiently high credit rating issued by private ratings agencies (van ’t Klooster 2023). Due to this policy choice, the EU has a chronic lack of safe assets (Gabor and Vestergaard 2018; Hill 2019; Leandro & Zettelmeyer 2019; Van Riet 2017).

A persistent misunderstanding remains that the issuance of more EU common debt is the only way to create large volumes of euro-denominated safe assets. This reflects a confusion between safe asset and “benchmark asset” status (i.e. that a debt’s value is used to price other assets). Since safe asset status merely depends on stable market value, any measure to reduce spreads between public debt of different EU issuers will increase the volume of euro-denominated safe assets. The ECB should abandon its policy of deference to U.S.-based credit rating agencies for risk screening euro-denominated public debt. It should also increase the effectiveness of its Transmission Protection Instrument for reducing spreads.

By approaching internationalisation as a market-driven process and neglecting offshore monetary governance, the combined activities of European actors have discouraged rather than incentivised the expansion of offshore euro creation and this undermined the objective of euro internationalisation. Our findings on the causes of the persistent failure of euro internationalisation may inform EU policymakers in their strategic thinking on which policies to pursue to achieve their objectives, a task all the more urgent in an era of crisis and change in the global monetary order.

Bateman, Will, and Jens van ’t Klooster. 2024. “The Dysfunctional Taboo: Monetary Financing at the Bank of England, the Federal Reserve, and the European Central Bank.” Review of International Political Economy, 31 (2), 413–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2023.2205656.

Caballero, Ricardo, Emmanuel Farhi, and Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas. 2017. “The Safe Assets Shortage Conundrum.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31 (3), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.3.29.

Cohen, Benjamin J. 2011. The Future of Global Currency. The Euro versus the Dollar. London: Routledge.

EC. 2019. “Strengthening the International Role of the Euro.” Commission Staff Working Document SWD (2019) 600 final. Brussels: European Commission.

———. 2021. “The European Economic and Financial System. Fostering Openness, Strength and Resilience.” COM(2021) 32/3. Brussels: European Commission (COM). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0032&from=EN.

Eichengreen, Barry, Arnaud Mehl, and Livia Chiţu. 2017. How Global Currencies Work. Past, Present and Future. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Gabor, Daniela, and Jakob Vestergaard. 2018. “Chasing Unicorns. The European Single Safe Asset Project.” Competition and Change 22 (1), 139–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/102452941875963.

Germain, Randall, and Herman Schwartz. 2014. “The Political Economy of Failure: The Euro as an International Currency.” Review of International Political Economy 21 (5), 1095–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2014.891242.

He, Dong, and Robert McCauley. 2012. “Eurodollar Banking and Currency Internationalisation.” BIS Quarterly Review June 2012. Bank for International Settlements.

Hill, Andy. 2019. “The Search for a Euro Safe Asset.” London: International Capital Markets Association (ICMA).

Juncker, Jean-Claude. 2018. “The Hour of European Sovereignty.” State of the Union Address 2018. Brussels: European Commission.

Leandro, Álvaro, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer. 2019. “The Search for a Euro Safe Asset.” Working Paper 18–3. Washington D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

McDowell, Daniel. 2012. “The US as ‘Sovereign International Last-Resort Lender’. The Fed’s Currency Swap Programme during the Great Panic of 2007-09.” New Political Economy 17 (2), 157–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2010.542235.

———. 2016. Brother, Can You Spare a Billion? The United States, the IMF, and the International Lender of Last Resort. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

McNamara, Kathleen R. 2008. “A Rivalry in the Making? The Euro and International Monetary Power.” Review of International Political Economy 15 (3), 439–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290801931347.

Mundell, Robert A. 1961. “A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas.” The American Economic Review 51 (4), 657–65.

———. 2002. “Monetary Unions and the Problem of Sovereignty.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 579,123–52.

Murau, Steffen, and Jens van ’t Klooster. 2023. “Rethinking Monetary Sovereignty. The Global Credit Money System and the State.” Perspectives on Politics 21 (4), 1319–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S153759272200127X.

Murau, Steffen, Fabian Pape, and Tobias Pforr. 2022. “International Monetary Hierarchy through Emergency US-Dollar Liquidity. A Key Currency Approach.” Competition and Change 27 (3-4), 495–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529422111866.

Pozsar, Z., & Sweeney, J. (2020). Covid-19 and Global Dollar Funding (Global Money Notes No. #27). New York: Credit Suisse.

Shin, Hyun Song. 2023. “Global Value Chains under the Shadow of Covid.” Speech at Columbia University 24 February 2023. Bank for International Settlements.

Spielberger, Lukas. 2023. “The Politicisation of the European Central Bank and Its Emergency Credit Lines Outside the Euro Area.” Journal of European Public Policy 30 (5), 873–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2037688.

Tooze, Adam. 2018. Crashed. How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World. New York: Viking.

Vallée, Shahin. 2010. “Behind Closed Doors at the ECB.” Financial Times Alphaville (blog). March 30, 2010. https://www.ft.com/content/bc9dde63-31ad-3caf-9b29-d66a8e768489.

Van ’t Klooster, Jens. 2023. “The Politics of the ECB’s Market-Based Approach to Government Debt.” Socio-Economic Review 21 (2), 1103–23, https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwac014.

Van ’t Klooster, Jens, and Steffen Murau. 2025. “Rethinking Currency Internationalisation. Offshore Money Creation and the EU’s Monetary Governance.” Journal of European Public Policy. Online First, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2025.2497357.

Van Riet, Ad. 2017. “Addressing the Safety Trilemma. A Safe Sovereign Asset for the Eurozone.” Working Paper Series No 35. Frankfurt am Main: European Systemic Risk Board.

Example for the sum in any currency of denomination (euro, dollar, or all) from the ECB database: Deposit liabilities vis-a-vis euro area MFIs reported by MFIs excl. ESCB in Germany (stocks) + Deposit liabilities vis-a-vis non euro area MFIs reported by MFIs excl. ESCB in Germany (stocks) + Deposit liabilities vis-a-vis non euro area Non-MFIs reported by MFIs excl. ESCB in Germany (stocks) + Deposit liabilities vis-a-vis euro area Non-MFIs reported by MFIs excl. ESCB in Germany (stocks).