This Policy Brief is based on Banco de España, Working Paper No 2515. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

What happens when more than one country simultaneously joins a trade bloc? Using the EU as a case study, we identify three key forces shaping trade and welfare: 1) integration between new and existing members; 2) new members adopting the bloc’s external trade policy; 3) integration among the new members themselves. Simulations show that the third force, the intra-candidate liberalization, can account at least for a third of trade and welfare gains, and in certain cases it can even exceed the effects of the other two forces combined. These findings highlight the importance of considering the different implications of trade integration and offer timely insights for the EU enlargement process, the EU-Mercosur agreement, and, more broadly, for many aspects of geoeconomic fragmentation.

The world is increasingly shaped by geoeconomic fragmentation – the global trend of countries rethinking trade ties due to geopolitical tensions (Campos et al., 2023; Attinasi et al., 2024). In this context, the European Union is actively considering the accession of several new members, including countries in the Western Balkans and Eastern Europe. At the same time, the EU has also reached several trade deals in the last few months, including the blockbuster deal with Mercosur, a trade bloc formed by four Latin American countries. In this context, understanding the real effects of trade bloc enlargement has never been more urgent.

In recent work (Campos and Timini, 2025), we explore what happens when more than one country simultaneously joins a trade bloc, using the European Union (EU) as a case study. We identify three key forces that shape trade flows and welfare outcomes in such scenarios:

The third force is the paper’s central insight. When more than one country joins a trade bloc (as in most EU enlargement episodes) the boost to trade among them can be just as important—or even more so—than their new access to the bloc’s existing members. The same logic applies when two trade blocs sign a trade agreement between them. For example, the EU-Mercosur agreement could trigger similar dynamics, in a scenario where South American countries will align more closely with the EU’s trade rules.

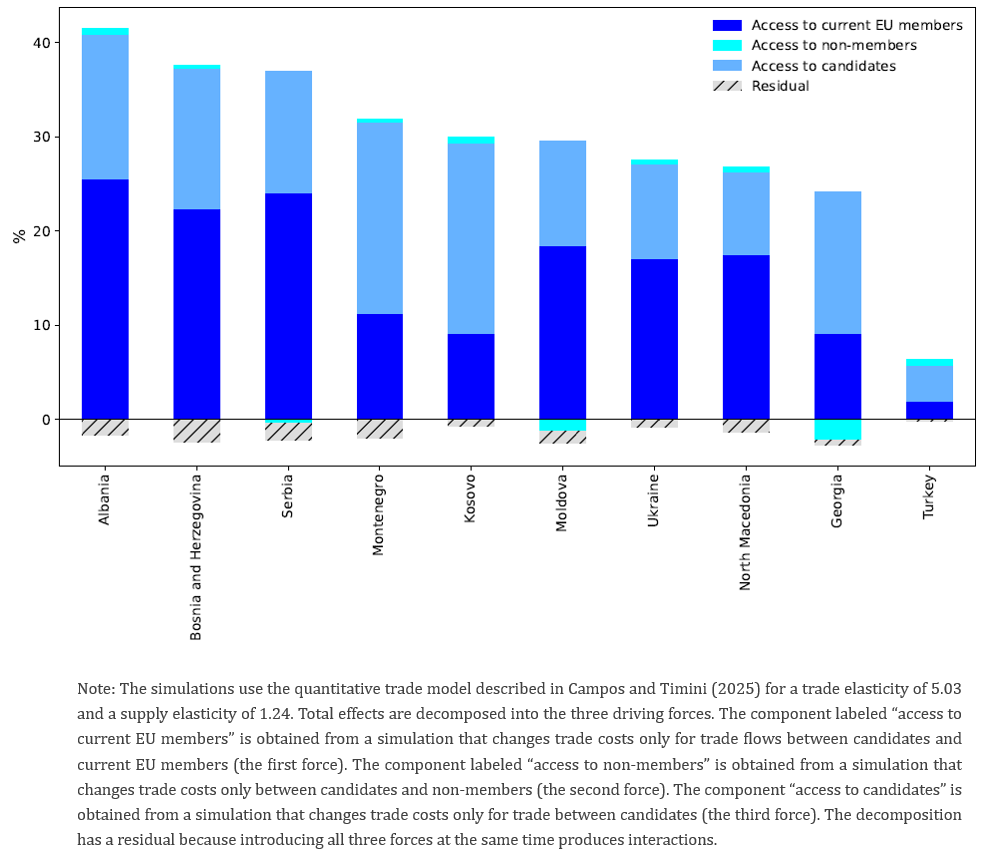

Simulations reveal a rich and nuanced picture of how trade and welfare evolve when more than one country joins a trade bloc like the EU simultaneously (see Figure 1).

The first force – easier access to the EU market – remains important. This is especially true for countries that faced high tariff and non-tariff barriers when trading with the EU before the enlargement. In such cases, the reduction in trade barriers with current EU members drives a significant portion of the gains.

The second force – adopting the EU’s external trade policy – has small effects. While generally positive, this component contributes only to a very minor portion of the trade and welfare gains (about 1% for the median candidate). In certain cases, its contribution might even turn negative, for countries that would have to renounce to established preferential access to key non-EU partners. For example, Georgia and Moldova would lose preferential access to countries such as Russia, China, and Kazakhstan.

The third force – easier access to new members’ markets – can be a game-changer. We calculate that for current candidates, this force accounts for at least one-third of total trade and welfare gains, and, in some cases, it can exceed that of the other two forces combined.

Figure 1. Trade gains from joining the EU for candidates

Importantly, these findings are not limited to EU enlargement. Similar dynamics would emerge in other contexts, such as the EU-Mercosur agreement, where cumulation of rules of origin or harmonization of standards1 among Mercosur countries could lower trade costs not just with the EU, but also among themselves (see e.g. Berganza et al., 2025; Cornejo et al., 2025).

For policymakers and analysts navigating today’s fragmented global landscape, this research therefore emphasizes the growing importance of a comprehensive ex-ante analysis of new association agreements and trade policy in general.

Attinasi M.G. and M. Mancini (eds.) (2024), “Navigating a fragmenting global trade system: insights for central banks”, ECB Occasional Paper Series n.365, December.

Berganza J.C., Campos R.G., A. Estevadeordal, E. Talvi, and J. Timini (2025), “UE-Mercosur: ¿plataforma hacia una nueva era de integración transatlántica e intrarregional”, Blog, Real Instituto Elcano.

Campos R.G.. J. Estefania-Flores, D. Furceri, and J. Timini (2023), “Geopolitical fragmentation and trade”, Journal of Comparative Economics, 51:1289-1315

Campos R.G. and J. Timini (2025), “Trade bloc enlargement when many countries join at once”, Banco de España Working Paper Series n.2515.

Cornejo R., A. Estevadeordal, and E. Talvi (2025), “Hacia un espacio económico integrado UE-América Latina”, Blog, Real Instituto Elcano.

Cumulation of rules of origin refers to the possibility for countries within a trade agreement to share production steps with other non-member countries, so that certain inputs are originating outside the agreement, but still benefit from preferential treatment granted by the agreement. Harmonization of standards means aligning technical regulations and product requirements across countries.