This policy brief is based on ECB Working Paper Series, No 3140. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

How do banks manage the behavioural maturity of non-maturing deposits (NMDs)? Although NMDs are contractually floating-rate liabilities with zero maturity, banks allocate them across different maturity buckets using models that reflect past depositor behaviour. Notably, only 20% of NMDs are treated as having zero maturity, while about 10% are assigned maturities beyond seven years. We assess whether these modelling assumptions are consistent with banks’ deposit structures. Results show that banks with more volatile, interest rate-sensitive, and digitalised deposit bases tend to assign shorter maturities, in line with the underlying risks. Yet during the recent monetary policy tightening, banks with more sensitive NMDs did not shorten assumed maturities or update their models to reflect changing market conditions. These findings underscore the critical importance of timely and accurate calibration of NMD assumptions for effective asset-liability management and financial stability.

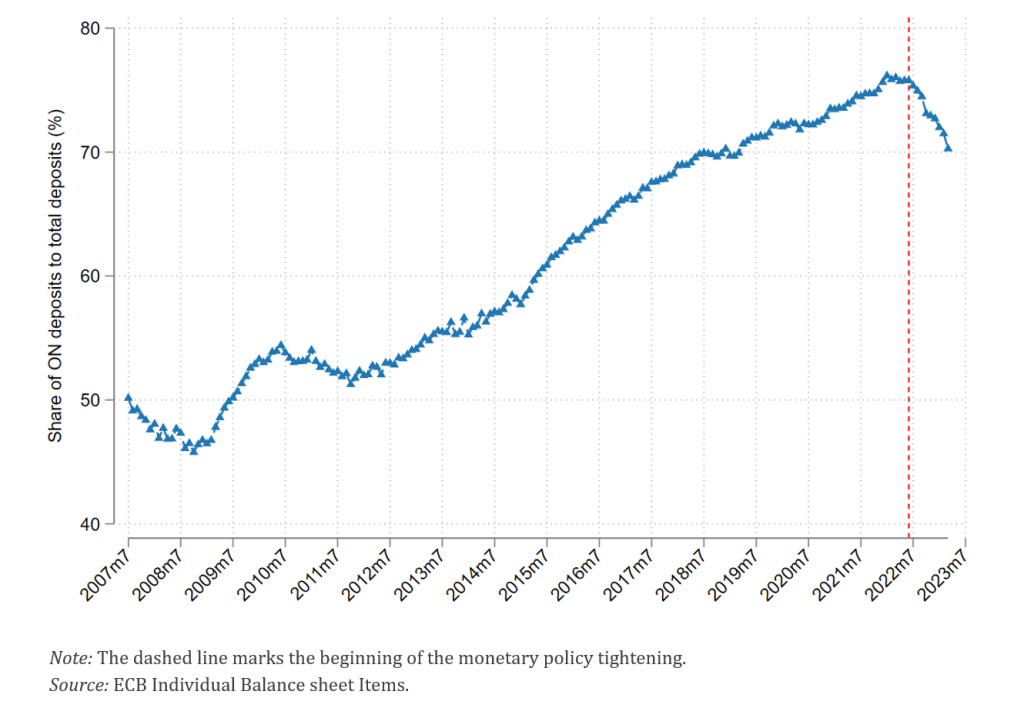

Deposit-taking is a core function unique to the banking sector, which relies critically on depositor confidence in the stability of the system. Since the 2007 global financial crisis, non-maturing deposits (NMDs), such as overnight deposits, have become an increasingly important source of bank funding (Figure 1). NMDs also play a central role in managing interest rates in the banking book (IRRBB) due to their distinctive features. More specifically, under contractual terms, NMDs are floating-rate liabilities with no stated maturity, allowing depositors to withdraw funds at any time without notice or penalty. In practice, however, these deposits tend to be very stable and are often held for extended periods (Drechsler, Savov, & Schnabl, 2021; Greenwald, Schulhofer-Wohl, & Younger, 2023; Jermann & Haotian, 2023).

Figure 1. Share of overnight deposits (July 2007-July 2023)

To estimate the actual maturity of NMDs, banks use statistical models grounded in assumptions about depositor behaviour drawn from historical data (the so-called behavioural assumptions). Depositors’ withdrawal decisions reflect a trade-off between immediate liquidity and the future, risk-adjusted benefits of keeping funds in the account, causing NMDs to behave more like long-term debt (Jermann & Haotian, 2023). As a result, behavioural maturities can diverge substantially from contractual maturities, offering a more realistic representation of the stability of NMDs. As such, they can help banks in managing maturity mismatches between assets and liabilities (Coulier, Pancaro, & Reghezza, 2024).

However, the unpredictability of depositor behaviour can challenge the assumption of sticky or stable NMDs. This became evident in recent episodes such as the 2023 U.S. bank failures and the sharp rise in interest rates in the euro area between 2022Q3 and 2023Q3, when depositors rapidly adjusted their behaviour in response to changing market conditions. Moreover, the ongoing digitalization of financial services may amplify these dynamics by enabling depositors to swiftly reallocate funds toward alternatives offering higher yields or lower perceived risks (Koont, Santos, & Zingales, 2024; Fascione, Jacoubian, Scheubel, Stracca, & Wildmann, 2025).

In Coulier, Pancaro, Pancotto, & Reghezza (2025), we draw on granular and confidential ECB supervisory data covering 67 significant institutions—representing around 72% of the euro area banking sector—from 2019Q2 to 2023Q3 to offer a comprehensive view of how banks model NMD maturities.

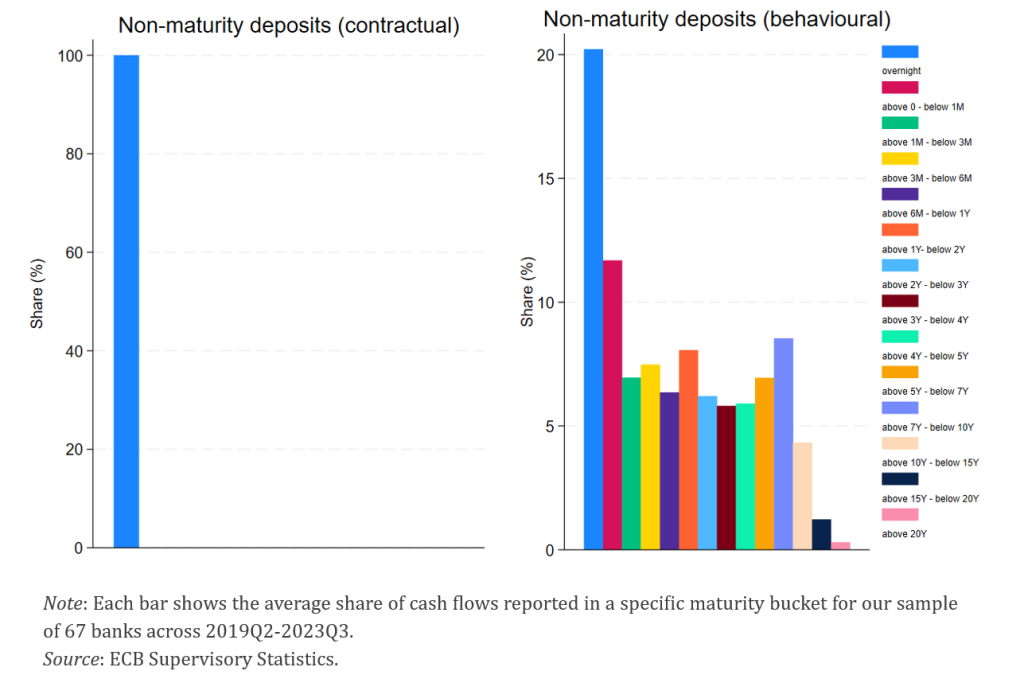

First, we provide descriptive evidence on how banks model NMD maturities. By comparing contractual and behavioural maturities, we uncover substantial differences. Figure 2 shows that only 20% of NMDs are effectively treated as floating-rate liabilities with zero maturity. A non-negligible portion (around 10%) of NMDs is assigned maturities exceeding 7 years and 1.5% are placed in maturity buckets above 15 years, suggesting that some banks consider these deposits as highly stable. On average, banks estimate behavioural NMD maturity at 1.99 years, with considerable variation across institutions (standard deviation of 1.33). Interestingly, we do not find such pronounced gaps in contractual versus behavioural maturities for deposits other than NMDs, such as term and redeemable-at-notice deposits.

Figure 2. NMDs – contractual versus behavioural assumptions

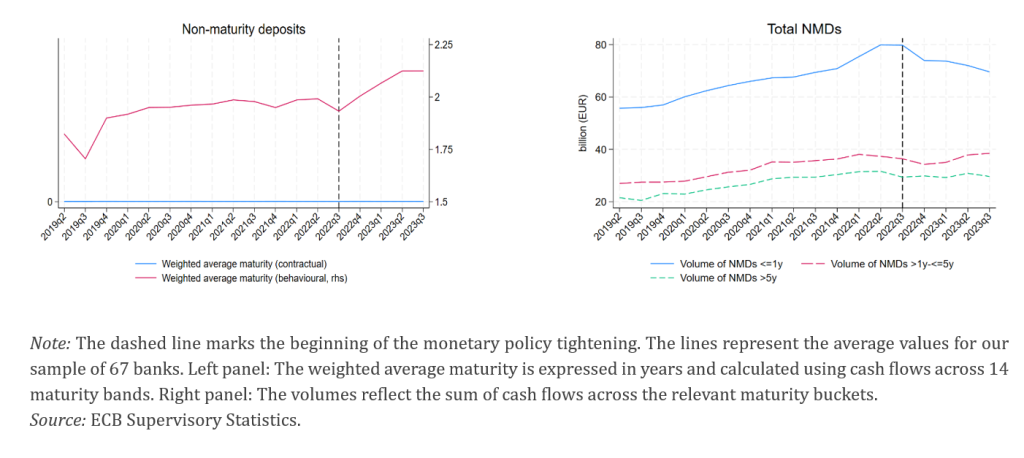

Looking at NMD maturities over time, the left panel of Figure 3 shows that the average behavioural maturity increases from 2 to 2.15 years following the onset of monetary policy tightening, despite the increase in deposit volatility. This pattern reflects a compositional effect where banks lost more volatile deposits (i.e., NMDs with behavioural maturities below 1 year) while retaining those deemed longer-term and more stable (above 1 year), as shown in the right panel of Figure 3.

Figure 3. NMD maturities over time

A key follow-up question is whether banks’ assumptions on NMD maturities accurately reflect the structure of their deposit bases. For instance, if banks with a higher share of unstable deposits—such as uninsured or digital deposits—assign longer behavioural maturities to NMDs (suggesting greater deposit stability), this may indicate an underestimation of outflow risks or, in extreme cases, “window-dressing” practices. Such behaviour could allow banks to mask asset-liability vulnerabilities by banking on NMD assumptions, which in turn could raise important financial stability concerns. To investigate this issue, we estimate bank-quarter panel regressions that regress behavioural NMD maturity on multiple deposit funding structure variables, while including a comprehensive set of bank-specific control variables along with bank business model and quarter fixed effects.

Importantly, we find no evidence of banks underestimating these risks over the full sample period. Banks with more volatile or interest rate-sensitive deposit bases consistently assign shorter maturities for NMDs. In particular, banks with a higher share of uninsured deposits report shorter behavioural NMD maturities. The same holds for banks with greater deposit sensitivity, as captured by the deposit beta, or a history of frequent deposit outflows. By contrast, banks with a higher share of household deposits—typically a more stable funding source—tend to assume longer NMD maturities.

Digitalization is another factor that can influence deposit stability. More specifically, digitalization can reduce deposit stickiness and increase rate sensitivity by allowing depositors to compare returns more easily and transfer funds quickly to alternative providers, including non-bank financial institutions. Consistent with this hypothesis, we find that banks with a larger share of digital deposits report shorter estimated NMD maturities. Finally, asset-side characteristics do not appear to influence how banks model NMD maturities.

Beyond confirming that banks account for the stability and interest rate-sensitivity of their deposit bases when estimating NMD maturities, it is also important to assess whether they adjust these assumptions in response to sudden changes in market conditions.

The sharp and largely unexpected increase in interest rates in the euro area between 2022Q3 and 2023Q3, which triggered a shift from overnight to term deposits, effectively reducing the stickiness of NMDs, offers a clear example of a sudden change in market conditions. In principle, banks with more volatile or interest rate-sensitive deposits should therefore face greater pressure to shorten their assumed NMD maturities to reflect an environment where deposits have become less stable. However, our results show no evidence of a differential adjustment in the assumed NMD maturity during this tightening episode. Specifically, banks with more volatile or interest rate-sensitive deposits did not reallocate their NMDs toward shorter-term maturity buckets.1

Generally, one would also expect swift updates of the internal models in this environment to account for changes in depositor behaviour. This is especially relevant given that these models were largely calibrated during a prolonged period of low interest rates, when the opportunity cost of switching to higher-yielding instruments or withdrawing funds was low and NMDs tended to be highly sticky. Descriptively, our confidential data indicate that only about half of the banks in the sample reported a change in their modelling assumptions between 2019Q2 and 2023Q3, while the other half made no such adjustments. Moreover, we find no significant difference in the share of banks reporting model updates before versus after the onset of monetary policy tightening.

Our regression analysis further shows that banks with more volatile or interest rate-sensitive deposits were not more likely to update their internal models following the onset of the monetary policy tightening. This finding suggests either that banks underestimated the potential risks associated with deposit volatility in a rapidly rising interest rate environment or that their internal models are adjusted only slowly in response to new conditions. Both explanations carry important implications for banks’ asset-liability and liquidity management and, ultimately, for financial stability if NMDs turn out to be more volatile than anticipated.

Our findings provide valuable insights for supervisors and policymakers. On the one hand, banks in our sample do not appear to underestimate deposit outflow risks or engage in window-dressing to mask asset-liability mismatches. Instead, they tend to calibrate their modelling assumptions in line with their balance sheet structures, with particular attention to liability-side characteristics linked to deposit stability. On the other hand, our results highlight that internal models used to estimate deposit stability are updated only infrequently. Given that renewed variability in policy rates and increased digitalization may have structurally altered depositor behaviour, banks may need to reassess their internal models to ensure that the estimated maturity of NMDs adequately reflects the evolving characteristics of their deposit bases.

Coulier, L., Pancaro, C., & Reghezza, A. (2024). Are low interest firing back? Interest rate risk in the banking book and bank lending in a rising interest rate environment. ECB Working Paper Series, 2950.

Coulier, L., Pancaro, C., Pancotto, L., & Reghezza, A. (2025). Banking on assumptions? How banks model deposit maturities. ECB Working Paper Series, 3140.

Drechsler, I., Savov, A., & Schnabl, P. (2021). Banking on deposits: Maturity transformation without interest rate risk. The Journal of Finance, 76(3), 1091-1143.

Fascione, L., Jacoubian, J. I., Scheubel, B., Stracca, L., & Wildmann, N. (2025). Mind the App: do European deposits react to digitalisation? ECB Working Paper Series, 3092.

Greenwald, E., Schulhofer-Wohl, S., & Younger, J. (2023). Deposit convexity, monetary policy, and financial stability. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Working Paper, 2315.

Jermann, U., & Haotian, X. (2023). Dynamic banking with non-maturing deposits. Journal of Economic Theory, 209, 105644.

Koont, N., Santos, T., & Zingales, L. (2024). Destabilizing Digital “Bank Walks”. NBER Working Paper, 32601.

We find similar results, albeit over a shorter period, when examining the period around the collapse of the Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023.