The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the institutions the author is affiliated with.

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally altered the relationship between the location of (knowledge) work and leisure, precipitating a global shift in housing preferences. This study investigates the “remote work shock” on urban housing markets, utilising Vienna as a high-resolution case study. By analysing a dataset of over 120,000 real-time rental listings from 2018 to 2022, we document a structural decoupling of housing value from traditional measures of “centrality.” The analysis reveals a significant “catch-up effect” where rents in Vienna’s peripheral districts have risen 50% faster than in the historic city centre, driven by a surge in demand for amenities conducive to remote work, such as outdoor spaces and additional rooms. These findings suggest that the monocentric city model is giving way to a polycentric or “flat” urban hierarchy. We argue that traditional, static housing policies are ill-equipped to manage this transition and instead propose to leverage real-time data to monitor gentrification, incentivise adaptive reuse, and ensure housing resilience in an era of hybrid work.

The modern metropolis was forged in the fires of the Industrial Revolution, organised around a singular logic: the separation of the home from the workplace. For nearly two centuries, this geographic schism dictated the rhythm of urban life, the engineering of mass transit systems, and, most critically, the valuation of real estate. The economic geography of the 20th-century city was defined by the “Bid-Rent Theory”— a foundational tenet of urban economics which posits that the price of land and housing is inversely proportional to its distance from the Central Business District (CBD). In this monocentric model, the city centre was the gravitational sun around which all economic value orbited. Residents faced a trade-off: pay a premium for accessibility and proximity to the workplace or accept the friction of a commute in exchange for more space and lower costs in the suburbs.

The COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally changed this relationship, as it was not merely a public health crisis but a spatial revolution. By forcing a global experiment in remote work, the pandemic shattered the assumption of physical necessity that underpinned the monocentric city. For the “knowledge economy” — the primary driver of wealth in global cities — production ceased to be a place one went to and became a digital state one entered. As office towers emptied and digital platforms like Zoom and Teams replaced physical boardrooms, the premium on centrality evaporated with startling speed. The home was transformed from a site of consumption and rest into a primary site of economic production, effectively collapsing the factory into the living room.

This shift has created a unique challenge for policymakers. As hybrid work stabilises into a permanent feature of the labour market, the mismatch between existing housing stock (designed for commuters) and emerging demand (from remote workers) is widening. Cities risk “data lag” — attempting to solve a 2025 housing crisis with 2019 maps.

This brief leverages Vienna as a “living laboratory” to study how the pandemic has changed housing demand, based on our recent study published in PloS One (the study provides more details on the research methodology). Vienna’s robust social housing infrastructure and historically stable market allow us to isolate the effects of changing preferences for individual amenities and locations. Using a dataset of 120,000 online rental listings, we map how the city’s value structure is being rewritten in real-time.

Our analysis reveals that the “remote work shock” seems to have inverted traditional gentrification patterns, driving a significant revaluation of the urban periphery.

The periphery outpaces the core

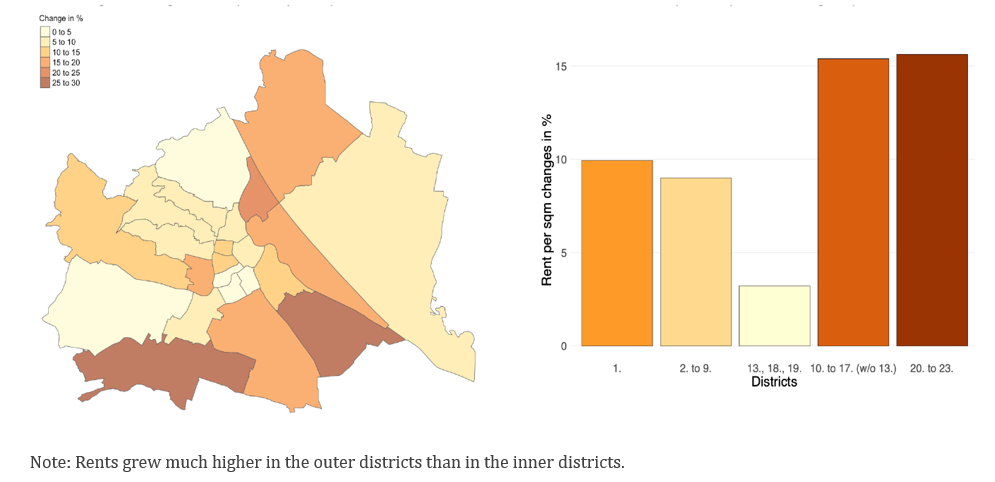

A striking empirical finding is the differential growth in rents. The premium on “centrality” has eroded as workers trade longer commutes for more living space. For example, the rent growth in the inner city districts (districts 1 to 9) rose by just under 10% from 2018 to 2022, while the average rent growth in the outer districts (districts 10 to 23) grew 50% more in the observation period.

This higher growth rate in the periphery indicates a “catch-up effect”. The outer districts, previously discounted due to commute costs, are closing the valuation gap, possibly because the necessity of daily commuting declined.

Figure 1. Rent growth in Vienna during the observation period

Not only the value of location changed during the pandemic, but also the use of residential space, possibly indicating a shift from “status” to “utility.” Our statistical models show that amenities conducive to remote work have seen their value double.

For example, outdoor spaces such as balconies, terraces, and gardens are no longer “nice-to-haves” but essential features for remote workers. Listings with these amenities commanded significantly higher premiums in 2022 compared to 2018.

Similarly, the number of rooms has become a stronger price predictor than pure square metres. This reflects the need for acoustic separation — the “Zoom Room” — over open-plan living in the hybrid work era.

The transition from a monocentric to a polycentric city, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, requires modernising urban planning to account for new spatial usage and commuting patterns.

Use all available data points

Our study shows that shifts in urban housing preferences can be isolated from price signals in online listing data. Urban planners should therefore aim to incorporate real-time data from alternative data sources, such as online listing platforms, to be informed about rent fluctuations and trends. Such data is available with very high temporal and spatial granularity. Data alliances and private-public partnerships should be established to make these privately held data points available and to tap into the data know-how of the real estate platforms.

Still, online listing data also comes with biases. Most importantly, they report asking prices rather than transactions. Such biases can be controlled for by micro-censuses and the use of available administrative data.

All these data points should be aggregated into an “urban housing dashboard” and made publicly available (while maintaining data privacy). A publicly available real-time data dashboard can help guide evidence-based discussions around housing and rent levels. It will help to make planning decisions and processes more transparent and, thus, contribute to more trust in public institutions.

Read price signals and development where the demand is

Price signals can only indicate scarcity and the need for new developments if they are not distorted by static rent caps that freeze the housing market in neighbourhoods. Urban planners should therefore focus more on identifying demand hotspots and targeting incentives for development there, rather than freezing the market structure in place.

Our analysis shows that particular types of dwellings are in higher demand in times of hybrid work than they were previously. Concretely, we find that family-sized, multi-room apartments with outdoor space in outer districts are in greater demand. As a reaction to data-driven demand shifts such as this one, city planners should pivot from “densifying the core” to “upgrading the periphery.” Zoning laws in outer districts should be relaxed to allow for slightly higher density if it includes amenities like balconies and shared workspaces that are needed for remote worker populations.

At the same time, there should be more incentives to convert obsolete office buildings (which face declining demand) into residential units. The same could go for ground-floor retail units in outer districts that are less in demand due to the constant hype around e-commerce, which could be developed into co-working spaces for the work-from-home population.

Managing “outward gentrification”

The “catch-up” in peripheral rents might indicate that a new form of gentrification poses a threat to lower-income residents who have historically found affordable housing in the suburbs.

As people who can work from home move outward to parts of the city that are attractive for remote workers, they might contribute to higher rents in these neighbourhoods and, hence, to the possible displacement of populations with lower income levels, who would normally have moved in the peripheral areas of metropolitan areas and commuted to the city centre for work.

To help vulnerable populations, housing allowances, energy subsidies, and targeted support programmes for long-term residents might help to prevent displacement in these rapidly changing districts.

The case study on the changing housing preferences in Vienna in reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic shows that urban landscapes are flattening. The traditional hierarchy between the city centre and the residential periphery is eroding, driven by a structural shift in how we live and work in times of hybrid work and ultra-connectivity. Real-time online data is available to track demand shifts related to this structural shift. Leveraging this data to understand the evolving spatial structure of housing demand, policymakers can foster a resilient, polycentric city that meets the needs of a post-pandemic population.