All authors are affiliated with the Andersen Institute for Finance and Economics. Alessandro Rebucci is a Professor at Johns Hopkins Carey Business School and an Andersen Institute Scholar.

Abstract

A future where global finance runs on-chain with stablecoins as the medium of exchange may be closer than we imagined a few months back. Following the recent passage of the GENIUS Act, major international organizations (e.g, Bhatt, 2025; BIS, 2025; IMF 2025) have started to focus on the promises of tokenization. In a new Andersen Institute white paper (ACNRS, 2025), we have analyzed the potential benefits and risks of dollar-backed stablecoins both under and outside the GENIUS Act1. In this brief, we broaden that discussion to the evolving nature of stablecoins and asset tokenization in a world that is increasingly fragmented. We argue that diverging international regulatory standards have the potential to undercut some of the benefits of tokenized finance by limiting portability, absent a private sector-led drive toward adopting compatible standards and protocols or a public sector-led harmonization of the regulatory frameworks.

Stablecoins are cryptocurrencies – virtual currencies living encrypted on decentralized ledgers – that are designed to maintain a stable value against a reference asset. These reference assets can be fiat currencies, comm to the U.S. dollar (USD stablecoins).

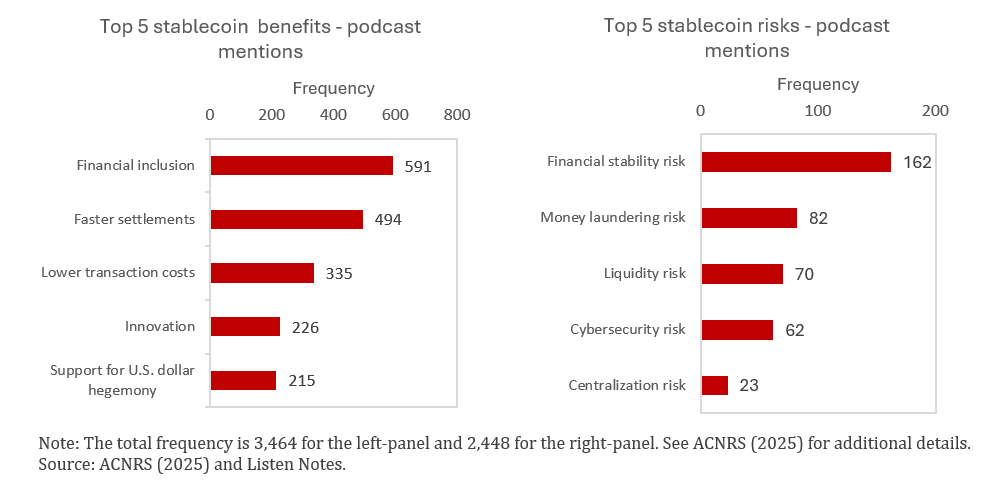

Survey evidence, case studies, and empirical analysis in ACNRS (2025) underscore the promises of stablecoins. For example, our LLM-based survey of expert opinions finds that stablecoins offer benefits which include faster and cheaper transactions and settlement, global and 24/7 portability, enhanced efficiencies from programmability, and increased financial inclusion (Figure 1, left-panel). Unlike volatile cryptocurrencies, stablecoins are more suited to serve as the settlement medium in tokenized markets. And unlike the traditional two-tiered banking system, stablecoin payments can settle directly, essentially instantaneously and 24/7 between digital wallets without reliance on interbank or central bank infrastructure.

However, the same experts recognize that stablecoins can carry risks, especially those that are not regulated (Figure 1, right-panel). Regulated stablecoins will have much lower risk once the GENIUS Act is implemented, but will continue to be subject to fraud, cyber and operational risk, and could increase the overall interconnectedness of the financial system.

Figure 1. Frequencies of podcast speaker mentions of stablecoin benefits (left) and risks (right)

Asset tokenization is the digital representation of real-world assets (RWAs) as programmable tokens on distributed ledgers.2 Asset tokenization could bring additional capital market activities on-chain through the tokenization of a variety of assets, including bank deposits, government and corporate bonds, loans, equities, commodities, and even real estate assets. Like stablecoins, other tokenized assets promise greater portability, lower transaction costs, shorter settlement times, but are similarly exposed to cyber, operational and fraud risk.

Tokenization also offers distinct benefits. By enabling fractional ownership, it can mitigate important indivisibility frictions in asset markets. It can also support high-frequency interest accrual and more efficient, near-continuous collateral management for both end investors and financial institutions. Particularly promising are applications in centrally cleared markets, where trades are novated to central counterparties (CCPs), as well as in real-time corporate cash and liquidity management, potentially resulting in deeper and more liquid markets. The programmability of tokenized assets can further reduce counterparty risk and search frictions. Trade finance is another area that appears ripe for tokenization. More generally, a future in which tokenized assets are used seamlessly in smart contracts, platform-based finance, and various DeFi applications is increasingly plausible. For these reasons, some international institutions view tokenization as poised to “improve the old by overcoming the frictions and inefficiencies of the current architecture, and enable the new” (BIS, 2025).

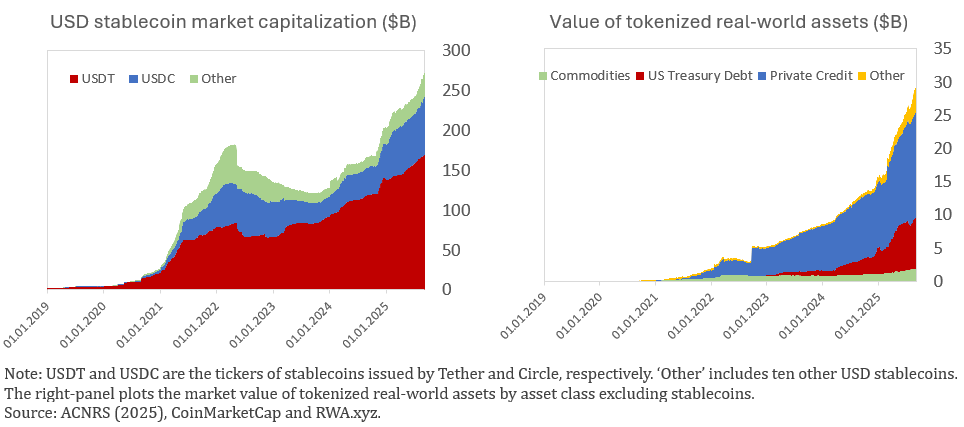

Stablecoins and tokenized asset markets are small and barely nascent. But there is widespread expectation that they will rapidly grow. USD stablecoins in circulation stand near $300 billion, with projections of a multi-trillion dollar market by decade’s end (Figure 2, left-panel).3 While the market for other tokenized assets is smaller, it is gaining momentum in both the U.S. and abroad (Figure 2, right-panel).4 Despite some regulatory uncertainty, major financial institutions are starting to issue tokenized funds on public blockchains. For example, BlackRock’s tokenized money market fund (MMF), although currently restricted to qualified institutional investors, was launched on the Ethereum blockchain in March 2024 and has surpassed $1 billion in AUM within a year. This past Summer, trading platform Robinhood began offering tokenized U.S. public and private equities to EU-based users.

Figure 2. Market capitalizations of USD-pegged stablecoins (left) and tokenized RWAs (right)

In light of tokenization’s potential, it is possible to envision a system in which stablecoins serve as the base medium-of exchange layer of a global ecosystem of tokenized assets. While tokenized RWAs are currently a very small share of the financial market, market participants anticipate that the combination of broader means of digital payment (especially for U.S. retail investors) and greater legal clarity will likely accelerate both the demand for and supply of tokenized assets, especially for more liquid instruments like MMFs and possibly equities.

Portability, which is increasingly seen in markets as crucial to the value proposition of stablecoins, refers to the degree to which stablecoins and tokenized assets can be seamlessly accessed, transferred, and used across networks, applications, and jurisdictions by users located around the world, without having to liquidate and re-establish their positions (and ideally without losing legal enforceability or tax attributes). Interoperability, which refers to one entity in one location working together with an entity in another location so that moving or using tokenized asset across them is seamless and legally enforceable, increases portability (Agur, 2025).5

Insofar as they live on public blockchains that share interoperable standards, stablecoins and tokenized assets are portable, that is to say borderless, and can contribute to increased international financial integration. Not surprisingly, demand for tokenized MMFs is currently coming mostly from countries in which access to international financial diversification is more costly.

However, if national jurisdictions fail to converge on common standards and protocols, then the benefits of tokenization will depend on the extent to which national borders impede portability. Consider for example stablecoins and tokenized assets at the time of conversion to fiat currency or if used for cross-border settlements. If a tokenized asset is legally prohibited from being offered in some jurisdictions, then users in those jurisdictions would have to pay significantly higher costs for obtaining, transferring, or converting that asset. Moreover, users outside those jurisdictions would also face barriers to sending the asset to users within those jurisdictions. As a result, diverging standards in even one jurisdiction could adversely affect portability, and at the extreme result in a loss of portability for everyone, thereby reducing the potential benefits from tokenization.

Fragmentation across national jurisdictions is a first-order obstacle to portability and interoperability in stablecoins and tokenized assets that can manifest itself along at least three different fault lines. First, geopolitical fragmentation reflects the fact that the United States, China and Europe have long had different approaches to managing financial innovation, and these differences may be amplified at times of geopolitical tensions. Second, regulatory fragmentation emerges when different authorities and jurisdictions impose heterogeneous and sometimes incompatible regulatory frameworks, divergences that normally would be worked out through international cooperation. Third, liquidity fragmentation results from liquidity siloed within platforms, trading venues, and payment systems, limiting fungibility and reducing the ease with which stablecoins and tokenized assets can fulfill their functions and promises.

Early signs of geopolitical and regulatory fragmentation can be seen in the diverging standards for stablecoins and digital finance across jurisdictions. The current geopolitical climate and marked differences in the role of the government in regulating financial activities are likely to make regulatory convergence more challenging than during previous periods of financial innovation under globalization. In fact, signs of such divergence have already emerged in the case of stablecoins.6 While history suggests that convergence toward common standards and protocols is still possible through private-sector led efforts, those episodes took place when broader international policy coordination was at its peak.

The United States continues to support an open capital account policy and the U.S. government has halted investigation of a central bank digital currency (CBDC), opting instead to support the development and widespread adoption of privately-issued stablecoins. Meanwhile, China remains committed to state-controlled, closed-border finance with efforts focused on CBDC development, or possibly, a stablecoin framework limited to the offshore yuan market. Europe appears squeezed in the middle, aiming to preserve an open financial system while attempting a dual approach to digital finance, with the adoption of a CBDC and regulated USD and euro stablecoins. In addition, an offshore, unregulated USD tokenized financial system is continuing to grow very rapidly.

As a result, under today’s deepening and likely persistent geopolitical fragmentation, regulatory divergence could accelerate, and international financial integration could significantly decline. Consider the case of stablecoins, where the GENIUS Act provides the foundations of the regulatory framework, although rulemaking is still being finalized. Further assume that the favorable regulatory stance in the U.S. will broadly extend to digital assets. In the current geopolitical environment, it is unlikely that formal international policy coordination (such as under the Basel framework for banks) could help resolve the existing differences. As a result, in the emerging segmented regime, the prospect of diminished portability and interoperability of stablecoins and tokenized assets across jurisdictions will likely add greater liquidity, settlement, and legal risks compared to a scenario resembling the integrated pre-pandemic period or before the global financial crisis.

In an alternative, more benign scenario, the lack of formal regulatory convergence could be overcome by private sector solutions, at least within geopolitically-aligned blocks. The U.S. has traditionally adopted a policy of “substitute compliance” and “mutual recognition” mechanisms in securities markets, which in the past has contributed to asset market regulatory convergence on U.S. standards even in the absence of formal coordination.7 Previous episodes of standard and protocol convergence were achieved through voluntary private-sector led adoption of U.S. norms, given the prominent position of the U.S. in global finance. Examples include the tightening of U.S. corporate governance and accounting standards following the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. In response, many countries adopted similar governance and disclosure rules to maintain access to global capital markets, including the UK, EU, Canada, Japan and Australia. And non-U.S. firms listed in the U.S. had to comply with comparable standards, effectively exporting U.S. regulatory norms globally. However, these episodes occurred when broader international policy cooperation was the norm and globalization was a common shared objective among most countries in the world economy.

While international policy cooperation may be losing its appeal, financial market infrastructures such as financial market utilities (FMUs) and central counterparties (CCPs), could play a critical role in lessening the risk of liquidity fragmentation by supporting cross-platform collateral mobility, harmonized margining, and more integrated liquidity pools. Ultimately, the effective degree of liquidity fragmentation in digital financial markets will depend on whether the market tips toward one or a small number of dominant infrastructures that benefit from scale and network effects or whether it remains structurally segmented.

It is possible that the financial dominance of the U.S. dollar system continues to create incentives strong enough for international participants to converge toward the U.S. regulatory standard for stablecoins and tokenized markets, or for financial market infrastructures to reduce costs of fragmentation by promoting common standards and putting in place adequate financial plumbing, thus facilitating portability and interoperability. Nonetheless, it is unavoidable to acknowledge that the policy environment has significantly moved away from the degree of international policy cooperation experienced during the peak of globalization.

As ACNRS (2025) concluded, regulatory frameworks such as the GENIUS Act or MiCA significantly lower financial stability risks associated with major financial innovations. However, a fragmented world along geopolitical and ideological lines, divergent regulatory approaches, without coordinating financial market infrastructures, all else equal, implies lower portability and interoperability because of the potential loss of common financial plumbing, raising the prospects of liquidity fragmentation within blocks and across jurisdictions. Barriers to portability create “islands” where some tokens move easily within a regime-compliant ecosystem but face liquidity, operational, or legal frictions when crossing regimes, especially when reserve disclosure standards, redemption rights, or interest treatment differ.

Under fragmentation, users desiring portability may seek out offshore tokenized systems. But this portability comes with much greater financial stability risks. Offshore stablecoins, such as Tether, are backed by different, often riskier reserve mixes and transmit shocks differently. Recently, ratings agency S&P Global downgraded Tether’s stability rating to the weakest possible grade, citing risky reserve assets, persistent reporting gaps and limited transparency.8

Stress from offshore markets could also spill over to regulated jurisdictions via redemption channels, potentially triggering runs or necessitating implicit cross-border bailouts. Moreover, the lack of public backstops and the absence of widely adopted CBDCs linking central bank liquidity to tokenized markets may compound these problems both inside and outside the United States.

In a highly fragmented world, the result is a higher likelihood that offshore market liquidity looks abundant on-screen but becomes non-fungible and non-transferable when it is most needed, a dynamic like the phantom liquidity within the banking sector described in Acharya and Rajan (2024). The absence of common regulatory guardrails could leave offshore tokenized markets opaque, fraud-prone, and manipulated.

To reap the full benefits of tokenization, the financial system must offer cross-jurisdiction portability and interoperability, while having appropriate prudential standards and financial infrastructures. Paradoxically, under a scenario of fragmentation, users may seek out unregulated tokenized markets that offer greater portability but carry much greater financial stability risks as we discussed in ACNRS (2025). As a result, the global financial system could also evolve into a collection of onshore and offshore, privately issued forms of tokenized money and assets with varying degrees of credibility, transparency, and portability, which would cut into the promised benefits of stablecoins and digital finance (Rey, 2025).

ACNRS (2025) explored the opportunities and risks of a global stablecoin ecosystem. In this brief, we broadened that discussion to asset tokenization and digital finance, emphasizing that a fragmented system may undermine the full benefits of digital finance.

Divergence between the GENIUS Act, MiCA, national CBDC efforts, and the persistence of offshore stablecoins risk creating a patchwork of only partially portable ecosystems that could undermine the benefits of digital finance, possibly introducing a trade-off between the portability and financial stability of tokenized markets.

The benefits of digital finance require both portability and financial stability. Portability and stability could be jointly sustained through regulatory convergence across jurisdictions. This includes common standards on reserves, redemption, disclosure, interoperability, and supervision. Historically, some episodes of financial regulatory harmonization came about through voluntary convergence toward the U.S. standard. Those episodes, however, took place at the peak of the globalization era of the 2000s characterized by an exceptional degree of broader international policy coordination.

Acharya, Viral V., and Raghuram Rajan. “Liquidity, liquidity everywhere, not a drop to use: Why flooding banks with central bank reserves may not expand liquidity.” The Journal of Finance 79, no. 5 (2024): 2943-2991.

Agur, Mr Itai, Mr German Villegas Bauer, Mr Tommaso Mancini-Griffoli, Maria Soledad Martinez Peria, and Brandon Tan. Tokenization and financial market inefficiencies. International Monetary Fund, 2025.

Ahmed, Rashad, James Clouse, Fabio Natalucci, Alessandro Rebucci, and Geyue Sun. “Stablecoins: A Revolutionary Payment Technology with Financial Risks.” Andersen Institute Whitepaper. Andersen Institute for Finance and Economics (2025). https://anderseninstitute.org/stablecoins-whitepaper/

Bank for International Settlements. “III. The Next-Generation Monetary and Financial System.” In BIS Annual Economic Report 2025, 24 June 2025. https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2025e3.pdf

Bhatt, Gita. “Technology, Payments, and the Rise of Stablecoins.” Finance & Development (2025).

International Monetary Fund. “Tokenization and the Financial System: Adapting to the New Landscape.” IMF Spring Meetings, 23 April 2025. https://www.imfconnect.org/content/imf/en/annual-meetings/calendar/open/2025/04/23/195251.html

Rey, Hélène. “Stablecoins, Tokens, and Global Dominance.” Finance & Development (2025).

Ahmed, Rashad, James Clouse, Fabio Natalucci, Alessandro Rebucci, and Geyue Sun. “Stablecoins: A Revolutionary Payment Technology with Financial Risks.” Andersen Institute Whitepaper. Andersen Institute for Finance and Economics (ACNRS, 2025).

Indeed, payment stablecoins are a form of tokenization. A broader definition of tokenization also includes blockchain-native instruments and crypto assets.

Citi Institute projects a $2 to $4 trillion stablecoin market by 2030: https://www.citigroup.com/rcs/citigpa/storage/public/GPS_Report_Stablecoins_2030.pdf.

Standard Chartered forecasts a $30 trillion tokenized asset market by 2034: https://www.swift.com/news-events/news/live-trials-digital-asset-transactions-swift-start-2025.

Put it simply, interoperability is about different systems being able to talk to each other and work together. Technically it means that protocols, blockchains, or platforms can exchange messages, settle transfers, or execute joint workflows because they share standards (messaging formats, token standards, APIs, etc.). Legally it refers to the rights embodied in a token being recognized and enforceable when the token moves across systems, jurisdictions, or infrastructures (e.g., a tokenized asset that can be used as collateral on another platform with the pledge being legally valid).

While stablecoin regulation has passed in the U.S., the Clarity Act, which provides guidelines for tokenized RWAs, is not approved yet.

Substitute compliance allows a foreign firm to comply with its home country’s regulation instead of the host country’s regulations, if the host regulator determines that the foreign rules are comparable to the host country’s rules. Mutual recognition is a reciprocal arrangement between jurisdictions, where each agrees to accept the other’s regulatory standards as sufficient for market access.

See: https://www.ft.com/content/974926ba-d295-4679-a4ed-7846b7f4242e.