This policy brief is based on OeNB Working Paper 268. The views expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank or the Eurosystem.

Abstract

The European Central Bank (ECB) is preparing to launch a digital euro. To achieve broad consumer adoption, policymakers must understand consumer preferences and the design features that matter most. Evidence from a choice experiment among Austrian consumers shows which features encourage uptake — and which do not. For most Austrians, security (protection against loss) and financial incentives matter most. Enhanced privacy — beyond what debit card payments offer — has little impact.

As the European Central Bank moves closer to launching a digital euro, one critical question remains: will consumers actually use it? While technical readiness is advancing, the success of a central bank digital currency (CBDC) hinges on widespread public adoption. This policy brief explores which features — such as privacy, security, cost savings, and offline functionality — matter most to consumers. By quantifying preferences across diverse demographic groups, our research (Elsinger et al., 2025) offers insights for policymakers and regulators.

Studying consumer preferences for a product that does not yet exist presents methodological challenges. Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) offer a rigorous approach by simulating realistic trade-offs and eliciting behavioral intentions. Building on recent applications of DCEs in South Korea (Choi et al., 2023) and Australia (Fairweather et al., 2024), our study contributes a European perspective to the growing literature on CBDC adoption.1

The sample consists of around 1,400 randomly selected Austrian residents aged 16 and older. Each respondent completed 10 consecutive choice tasks. In each task, they chose between two variants of a digital euro or their current payment instrument. Respondents could also opt out of the experiment, e.g., due to a lack of interest in a digital euro.

The digital euro variants presented to respondents were bundles of the following five attributes:

These attributes broadly align with the design features currently being discussed by the ECB and the legislative proposals by the European Commission. Salient features like convenience of use, payment speed, etc. have been pre-emptied by showing respondents a video clarifying that a digital euro will be convenient, easy to use and fast. We disregard the store of value function (as it will be limited) and interest rates. We informed respondents that the digital euro will be universally accepted (in line with the legislative proposal of the European Commission).

The observed choices allow us to infer respondents’ underlying preferences and assess the relative importance of these attributes. By estimating mixed logit models, we identify significant heterogeneity in adoption likelihood across socio-demographic groups, payment preferences, and satisfaction with existing payment methods.

The results are clear: security and financial incentives are the most important drivers of acceptance.

Although privacy is a major topic in public debate, the experiment shows that increased transaction privacy plays only a secondary role in actual decision-making. Specifically, a fully anonymous digital euro increases adoption likelihood by just 1 percentage point, on average, compared to a model where the user’s bank can see transaction data (similar to current debit card payments).

The average masks significant heterogeneity: for about two-thirds of respondents, financial incentives outweigh privacy concerns. These consumers trade-in lower privacy for monetary incentives – a behavior addressed as privacy paradox in the literature (see e.g. Acquisti et al. 2016).

For the remaining third of respondents, however, privacy is paramount: The adoption level is lower, and consumers are not willing to give up privacy in exchange for monetary compensation.

The ability to use the digital euro without an internet connection had a modest effect (+4 percentage points). Access via card increases adoption likelihood by 6 percentage points compared to an app. This reflects population heterogeneity: about two-thirds of respondents prefer a card. Van der Horst and van Gent (2025) also report a card preference for the Netherlands. This may be attributable to the fact that smartphone-based payment apps are used by only a relatively small fraction of Austrians at present.

Simulations suggest that around 45% of respondents would be willing to use a digital euro — assuming an implementation we consider realistic: no financial incentives, limited privacy (e.g., banks can access transaction data), no protection against loss or theft, card-based access, and offline functionality.

In contrast, in an idealized (but unrealistic) scenario — full privacy, €10 monthly savings, full loss protection, and card access — 74% would be willing to use it.

These figures suggest that there is genuine interest in a digital euro — even if it does not meet all ideal criteria.

Unsurprisingly, younger, more educated, and tech-savvy individuals are more likely to adopt the digital euro. For example, a 20-year-old is 18 percentage points more likely to use it than a 50-year-old. Trust in the central bank also plays a major role: those who trust the Oesterreichische Nationalbank are 15 percentage points more likely to adopt.

Another key factor is satisfaction with current payment methods. Those who cannot always use their preferred method are 13 percentage points more likely to adopt the digital euro.

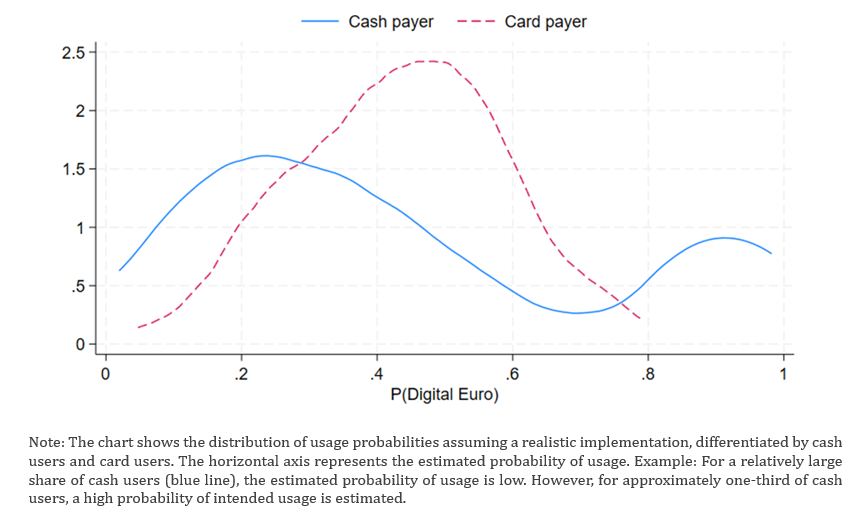

On average, there is no significant difference in adoption likelihood between those who currently pay mostly by card/app and those who prefer cash. Again, the average masks an important heterogeneity: about one-third of cash users show high willingness to adopt the digital euro — especially if they are dissatisfied with current options. The remaining two-thirds show little interest.

Figure 1. What is the likelihood that cash and card payers will use a digital euro?

Our findings offer valuable guidance for policymakers and CBDC designers:

Our study shows that a well-designed digital euro could gain broad acceptance — even in a cash-friendly country like Austria. The key is to offer real benefits, ensure security, and build trust. These insights provide a solid foundation for further discussion and for shaping a digital payment system that meets people’s needs. On a methodological note, the discrete choice experiments delivered robust results which are helpful for understanding the heterogeneities among the population. Running the same experiment in other euro-area countries would reveal whether these patterns generalize Additionally, it would be interesting to analyze whether other attributes are valued by consumers, such as the contribution of a digital euro to the autonomy of the euro area.

Acquisti, A., Taylor, C. R. and L. Wagman (2016). The Economics of Privacy, Journal of Economic Literature 54(2), 442–492.

Choi, S., Kim, B., Kim, Y. S. and O. Kwon (2023). Predicting the Payment Preference for CBDC: A Discrete Choice Experiment. BIS Working Papers No. 1147. https://www.bis.org/publ/work1147.pdf.

Elsinger, H., H. Stix, and M. Summer (2025). Consumer Preferences for a Digital Euro: Insights from a Discrete Choice Experiment in Austria. OeNB Working Paper No. 268.

Fairweather, Z., Fiebig, D., Gorajek, A., Guttmann, R., Ma, J. and J. Mulqueeney (2024). Valuing Safety and Privacy in Retail Central Bank Digital Currency. Reserve Bank of Australia Research Discussion Paper No. 2024-02.

Georgarakos, D., Kenny, G., Laeven, L. and J. Meyer (2025). Consumer Attitudes Towards a Central Bank Digital Currency. ECB Working Paper No. 3035.

Van der Horst, F. and A. van Gent (2025). The Offline Digital Euro and Holding Limits: A User-centred Approach. De Nederlandsche Bank Occasional Studies No. 25-2.

Other survey experiments on the digital euro have been conducted by van der Horst and van Gent (2025) and Georgarakos et al. (2025).