Climate change poses large economic costs to governments and societies. Reducing individuals’ CO2 footprints is central in mitigating climate change. In a new paper, we show that providing information on combating climate change motivates individuals to take costly actions to offset CO2 emissions. Presenting the information as the result of scientific research is as effective as framing it as the behaviour of other people. Individuals’ responses vary depending on their socio-demographic characteristics and attitudes towards climate change. Furthermore, individuals choose information that aligns with their views. Individuals who actively gather information about climate change have a higher willingness to pay for carbon offsets.

Climate change poses large economic costs to governments and societies. Individuals substantially contribute to the increase in greenhouse gases through their everyday consumption choices (Hertwich and Peters, 2009). Hence, they can help mitigate climate change by taking actions that reduce their CO2 footprints. The extent to which individuals take action to fight climate change may depend on various factors such as their views towards society and the environment, the behavior of their peers, and their information on ways to reduce emissions. Yet, so far little evidence exists on how individuals react to information about climate change. Understanding the impact of climate information on individuals’ behaviour is crucial for the design of effective information campaigns aimed at motivating people to reduce their CO2 footprints.

In a new paper, we shed light on how the provision of information about climate change induces survey participants to take costly actions to fight climate change. Using data from a large survey representative for the German population, we administer an experiment in which we randomly expose participants to information on ways to reduce individual CO2 emissions. We then study whether subjects in the treatment groups adjust their willingness to purchase carbon offsets (WTP) differentially compared to those in the control group that did not receive any information. Additionally, we aim to understand whether individuals would actively acquire information on climate change in real life. To this end, we conduct an endogenous information experiment, in which survey participants face an information selection choice.

In our first experiment, we randomly assign individuals to four treatment groups and one control group. The treatment groups receive truthful information on ways an individual may reduce her own CO2 emissions, that is, through adjusting daily consumption choices but also through reducing travel by air and car. We vary the framing of the information between the treatment groups to study whether different framings of identical information are differentially effective in changing individuals’ behaviour: Two groups receive information framed as scientific research (scientific framing) and two groups receive information on the behavior of people like them (peer framing). The control group receives some sentences without any substantive information content. We elicit individuals’ willingness to purchase carbon offsets both before and after the information provision. In order to avoid repeating the same question twice in the survey, we elicit prior and posterior willingness to pay (WTP) in different formats, for intra-European flights for the prior and for transatlantic flights for the posterior.

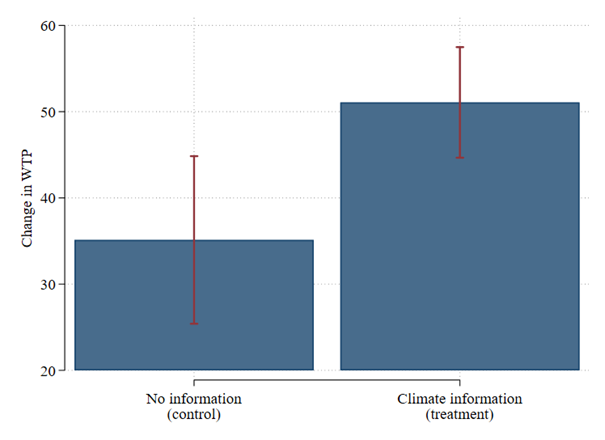

Figure 1 shows that providing information on actions to fight climate change increases individuals’ WTP for voluntary carbon offsetting. Respondents in the treatment groups increase their WTP by EUR 15 on average relative to the control group. The effect is substantial as it corresponds to about one-third of the overall difference between the posterior and prior WTP.

We find that framing the climate information as the behavior of peers is just as effective as framing it as scientific research. All treatments result in an economically and statistically significant increase in WTP relative to the control group. While the point estimates of the peer framing are larger than the scientific framing, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that they are statistically identical.

Figure 1: Effect of providing information about climate change on willingness to pay (WTP) to offset CO2 emissions

Source: Bundesbank Online Panel Households (BOP-HH), August 2020.

Note: This figure shows the effect of providing information about climate change on individuals’ willingness to pay (WTP) for offsetting carbon emissions. The bars indicate the average change in WTP for respondents in the treatment and control group. The change in WTP is defined as the difference between prior and posterior WTP. Solid lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Results are weighted.

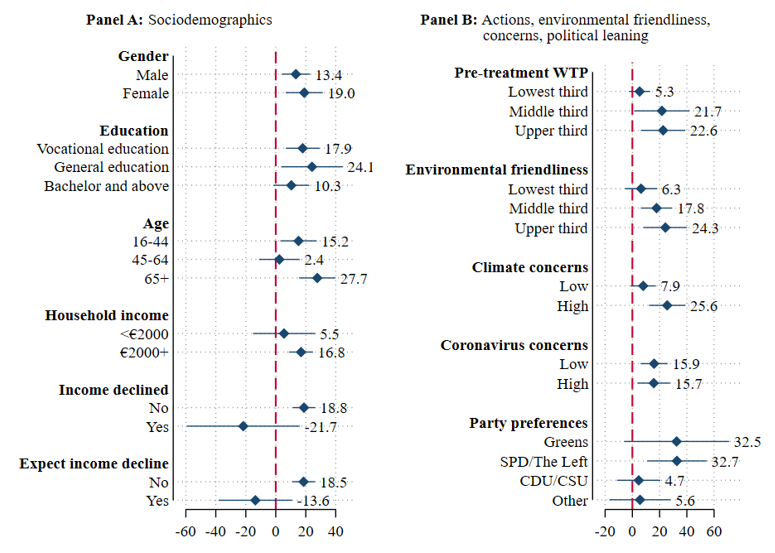

The treatment effect varies systematically across socio-demographic groups. Figure 2 illustrates that women react more strongly to the provided signal. Moreover, individuals with secondary but no tertiary education are most responsive, as are older survey participants. Financial constraints also matter. Participants with lower earnings (below EUR 2,000) do not adjust their WTP after the treatments, similar to participants who lost or expect to lose income due to the pandemic.

Participants that were ex ante more positively disposed towards fighting climate change display a stronger reaction to the information treatments. Individuals with a higher pre-treatment WTP, a higher degree of climate concerns, and those with a strong environmental stance are more responsive. In contrast, individuals with a high degree of coronavirus concerns react slightly less. Further, political preferences play an important role. Supporters of the center-right party (CDU/ CSU) do not react at all, nor do supporters of other smaller parties including the far-right party (AfD). In contrast, supporters of center-left and far-left parties (SPD/ Die Linke) increase their WTP by more than EUR 30 in response to the information treatments. The treatment effect for supporters of the Green party is similar in magnitude though less precisely estimated. Overall, these results indicate that increasing people’s WTP by informing them about how to fight climate change is contingent on people’s ideological orientation and prior stance towards the environment.

Figure 2: Treatment effect heterogeneity by respondents’ characteristics

Source: BOP-HH, August 2020.

Note: This figure illustrates heterogeneity in responses to the provision of information, showing point estimates of the pooled treatment effect (T1-T4) for different subsamples. Solid lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. “Income declined” and “expect declining income” refer to individuals who report they have reduced their consumption during the coronavirus crisis due to realized or expected income losses. The point estimates of the treatment coefficients are statistically different from each other across subgroups for the following variables: Age (45-64 vs. 65+), income declined, expect declining income, pre-treatment WTP (bottom vs. top third), environmental friendliness (bottom vs. top third), climate concerns, party preferences (SPD/The Left vs. CDU/CSU & Other).

Individuals in real life have a choice of whether or not to actively acquire information about climate change. We administer an endogenous information experiment to study whether survey participants are interested in acquiring information about the climate. We offer them the choice between short articles about climate change and population ageing, or no information at all.

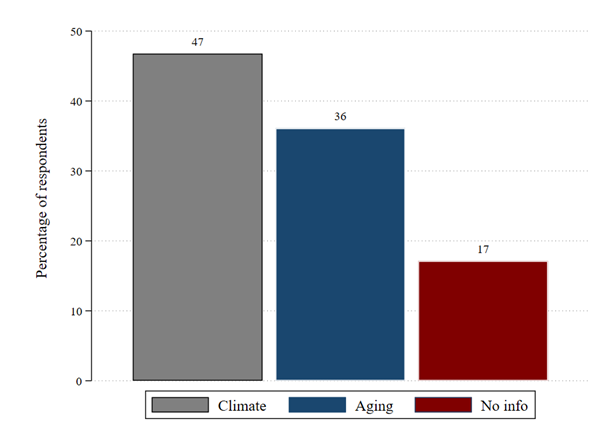

Figure 3: Selected information

Source: BOP-HH, March 2021.

Note: This figure reports the percentage of respondents that chose to read information on climate change, aging of society, and no information, respectively. Results are weighted.

We document widespread interest in climate change as about half of the survey population (47%) choose the climate change article (Figure 3). However, the other half of the population does not want to acquire further information on climate change. 36% choose the article about ageing, and 17% do not want to read any article.

We explore the heterogeneity in information selection by studying multivariate relationships between the choice of a certain topic and sociodemographics, as well as attitudinal factors. Attitudes towards the environment and population ageing significantly predict article choices: Respondents scoring high on a scale measuring the stance towards the environment or the aging of society are more likely to choose the article on the respective topic. Further, university educated and younger survey participants are more likely to choose the climate change article and less likely to choose the aging article than others. Women, on the other hand, display a higher propensity to choose the article about population aging. Last, supporters of the Green party and those with a higher prior WTP are more likely to select the article about climate change, than others. In sum, these correlations suggest individuals choose articles that largely align with their prior stance towards certain topics and avoid information that might challenge their existing beliefs, in line with motivated beliefs, and dissonance avoidance in particular.

Our study demonstrates that providing information about measures to combat climate change increases individuals’ willingness to pay for voluntary carbon offsetting. Framing the information as the behavior of peers is just as effective as framing it as scientific research. Furthermore, individuals with more positive environmental attitudes are more likely to select information about climate change, suggesting that individuals choose information that largely aligns with their prior stance towards a topic and disregard information that might challenge their existing beliefs. Overall, our results suggest that informing individuals of ways to combat climate change can be a powerful tool in persuading them to reduce their carbon footprint. However, successful information campaigns aimed at mitigating climate change have to find creative ways to reach individuals that would normally not actively seek information on climate change.

Bernard R., P. Tzamourani and M. Weber (2021). “Climate Change and Individual Behavior”, Bundesbank Discussion Paper No 01/2022, February 2022.

Hertwich, E. and G. Peters (2009). Carbon footprint of nations: a global, trade-linked analysis. Environmental Science & Technology 43(16), 6414–6420.