This policy brief is based on IMFS Working Paper No. 218 (2025).

Abstract

Payment costs for consumers are difficult to determine, are not recorded in an internationally harmonized manner and vary significantly from country to country. They are incurred in many forms, for example as fees for account management, for cash withdrawals at ATMs or for payment cards and also as financial damage in the event of loss or fraud. In addition, these costs include time costs, e.g. for cash withdrawals or the payment process, and costs of data disclosure. To determine the total costs and facilitate international comparisons, different key figures on a comparable basis are calculated, such as the cost per transaction and as a percentage of the transaction value. The focus of the paper is on a critical review of the literature on cost studies at the consumer level. In particular, the results of existing work are compared, and the most important cost categories are identified. We find some key cost drivers and show how the results are driven by key assumptions.

Costs play a central role in the decision which means of payment to use. Banks, consumers and retailers are likely to give priority to offering, using and accepting means of payment that incur relatively low costs. There are a number of studies that examine the costs of means of payment for different countries and currency areas. Most of them focus on the retail sector and payment service providers. So far, only a few have looked at the costs at consumer level although it is finally the consumers who make a choice between the available means of payment.

Due to the specifics of national payment systems, cost studies usually focus on individual countries. In what follows, we present these cost calculations on a harmonized and comparable basis. Moreover, we carry out some sensitivity analyses with respect to underlying assumptions and identify main cost drivers. We focus on private costs (which are essential for individual decision making) incurred by consumers when making payments by cash, debit card or credit card.1 These range from fees (e.g., for card payments, ATM withdrawals), financial losses due to the loss of a means of payment or fraud, opportunity costs of time (e.g., payment time, ATM withdrawals, checking of account statements) to costs incurred by consumers through data disclosure.2 Private costs also include implicit costs when costs of other sectors are passed on to consumers by retailers and banks, thereby increasing product prices. It is, for instance, conceivable that merchants pass on the costs of a relatively expensive payment method to product prices and increase them for all consumers because surcharging is not allowed for the use of a particular payment method.

We concentrate on papers published in the last 25 years which include the costs of means of payments for consumers. These cover 12 countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Norway, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, USA, Uruguay) and one multi-country study with data on 52 countries from all continents. The calculated and harmonized metrics are the private costs per transaction and the costs as a percentage of the transaction amount (see figs. 1 and 2 where the year refers to the year of investigation).

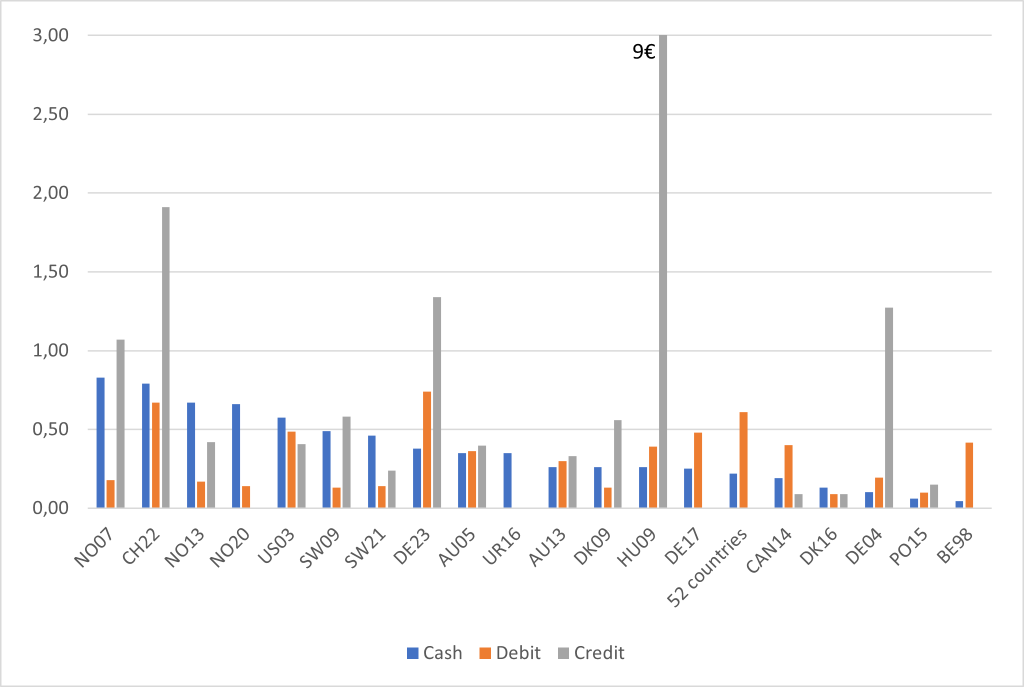

Figure 1. Private costs per transaction (in euros)

Note: DE17 from multi-country study (refers to ATM transactions); DK09/DK09eCom: face-to-face/distance selling; US03 (AU05): for selected transaction amounts: Cash $10 ($11), card $50 ($54). Conversion to € using the average exchange rate for the survey year.

In their multi-country study, Carbo-Valverde & Rodriguez-Fernandez (2019) compare the costs of cash and debit cards. The lowest per-transaction cash costs for consumers can be found in Europe, Africa and the Asia-Pacific region, while the highest costs are in North, Central and South America. No such clustering can be observed for debit cards where high costs exist in the US, Sweden, Poland and Russia. However, for all countries included, cash is cheaper than debit cards and the costs are driven by fees.3

The results of the individual country studies differ significantly from year to year and country to country, regardless of the indicator used. The wide range of results is also striking, even for estimates for one country (see Australia, Denmark, Norway, Switzerland). Based on the costs per transaction (see fig. 1), there are considerable differences for all payment instruments. For example, private cash costs range from €0.05 to €0.83, while the extreme values for debit cards are €0.13 and €0.67. For credit cards, the differences are particularly extreme, with a minimum of €0.09 and a maximum of almost €9. It should also be emphasized that there is no uniform picture with regard to the relative costs of the three payment instruments. In some studies, cash is associated with the highest costs for consumers (e.g. Norway, Sweden 2021, US 2003). In other countries, the three instruments are roughly on par (e.g. Australia). Finally, there are also countries where cash is least costly for consumers (e.g. Hungary, DE23, DE17, Poland). Looking at the costs over time and per country, there appears to have been a downward trend in costs.

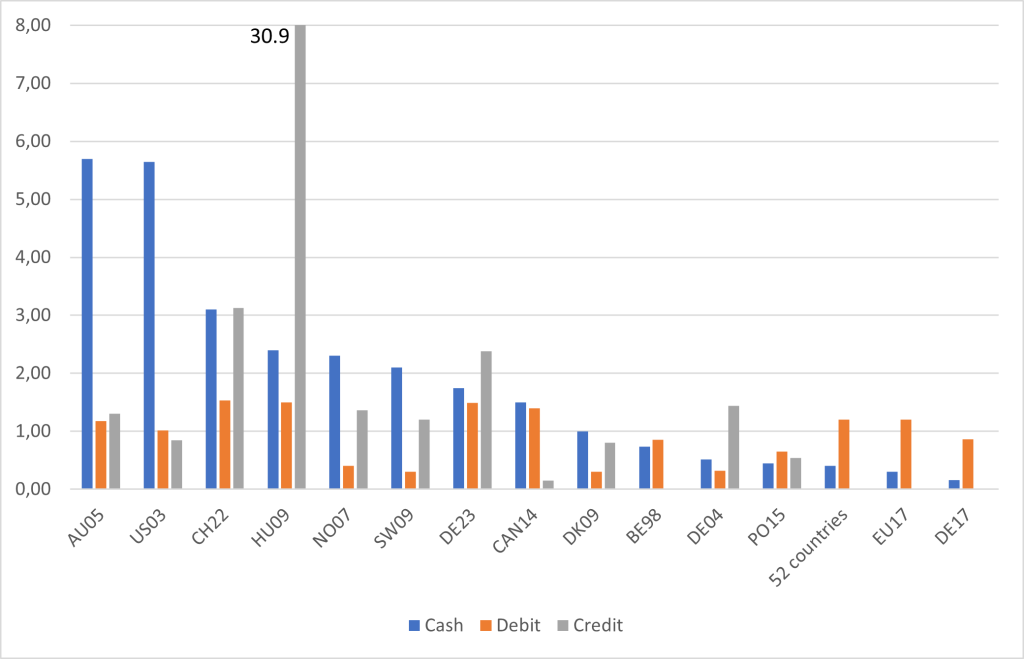

When the costs are set in relation to the transaction amount, there are again considerable differences between countries and payment instruments (see fig. 2). They range from 0.16 % to 5.7 % for cash, from 0.3 % to 1.5 % for debit cards and from 0.15 % to 30.9 % for credit cards.4 In many cases, however, a clear ranking of costs can be determined for this indicator. In most countries, cards, especially debit cards, are cheaper than cash. The widest ranges can be found in Australia (2005), the USA (2003), Sweden (2009) and Norway (2007). This is due to the fixed cost element, which has a greater impact the smaller the transaction values are. And many small amounts are paid with cash in particular. In order to eliminate the effects of different transaction values, the Australian and US studies work with predefined standard amounts. Nevertheless, there are also some rare cases in which cash is the most cost-efficient means of payment (e.g. DE17, EU17, PO15).

In addition to differences in methodologies, the status and development of the national payment systems and the respective cost types considered, the following factors are the main contributors to this pronounced variability in results:

The share of payment costs borne by consumers varies from 3 % in Canada (credit cards) to almost 75 % in Hungary (credit cards). Cash accounts for between around 14 % (Norway 2020) and up to 80 % (Uruguay) of consumers’ total means of payment costs.

Figure 2. Private costs as a percentage of the transaction amount

Note: DE17(EU17) from multi-country study (refers to ATM transactions); US03 (AU05): for selected transaction amounts: Cash $10 ($11), card $50 ($54).

A particularly important cost driver are time costs, which are included in the cash procurement costs and payment time as well as the checking of payment receipts and account statements. The time required must be estimated and valued. Depending on which of these time costs are included, how the necessary amount of time is measured and how time valuation is carried out, the results differ significantly.

Estimation and valuation of transaction times is not trivial, as the example of a cash withdrawal at an ATM shows. It initially seems plausible to determine the time it takes to get to an ATM and then assign a price to this in terms of opportunity costs (“Approach 1”). Many studies follow this approach (e.g. Sveriges Riksbank, 2023; Trütsch, 2024). In this case, the time spent withdrawing cash is simply multiplied by a “representative” hourly wage rate and the total number of ATM withdrawals made per year. However, the question arises as to whether the consumers really have the choice between increasing their working hours and making a payment. Under certain circumstances, the actual opportunity costs of leisure time would be much lower. Therefore, in many cases only part of the hourly wage is recognized as an opportunity cost of time (see, e.g., Knümann et al., 2024). But even in this case, estimates of time costs are relatively large.

However, when observing actual behaviour (withdrawal amounts and the frequency of withdrawals), these costs do not appear to be substantial for consumers. Otherwise, they could simply reduce these costs by going to the ATM less often and withdrawing higher amounts each time. Moreover, in many cases, people do not necessarily make an extra trip to the ATM, but rather get cash when they are already nearby. In addition, there are also the possibilities for cash-back.

The revealed preferences thus show that consumers apparently do not consider the (opportunity) costs of ATM withdrawals to be too severe. Therefore, some authors follow a model-led approach (“Approach 2”), e.g. based on the Baumol-Tobin model, to determine the cost per cash withdrawal from the number of ATM transactions per person and an interest rate (opportunity cost of holding cash), see e.g. Carbo-Valverde & Rodriguez-Fernandez (2019). A major difficulty with this approach is estimating the opportunity cost of holding cash. Should a credit or debit interest rate be applied? It should also be considered that cash is subject to a risk of loss and that this is a decision under uncertainty, including a risk premium.

Approach 1 generally leads to significantly higher costs than approach 2 (see Knümann et al., 2024, 30ff.). Accordingly, the time costs dominate the total cash costs for consumers in case 1. In approach 2, on the other hand, they are negligible, i.e. the costs are dominated by fees (see Carbo-Valverde & Rodriguez-Fernandez, 2019).

There are even major uncertainties when it comes to calculating the fees. The basic problem is that access to and deposit of cash are closely linked to the current account. Most customers use their debit card to obtain cash. This raises the question of how account fees and card fees should be split. In any case, a portion should be allocated to cash. However, such a procedure is inevitably arbitrary. In the case of credit cards, there are usually explicit (annual) fees. In the case of debit cards, this is often not the case and a portion of the account fees would therefore have to be distributed between cash and cards.

Another challenge is comparing the costs of different payment instruments. This is problematic because the typical payment amount differs from instrument to instrument. The average card payment is generally much higher than the average cash payment. In addition, there are also differences between the average value of debit and credit card payments. For this reason, Garcia-Swartz et al. (2006a, b) calculate the costs for fixed payment amounts. Methodologically more convincing is the approach of establishing cost functions for each payment instrument. However, the results of such estimates rely on strong assumptions. In addition, such estimates often do not include consumer costs or do not show them separately. One exception is Kosse et al. (2017) for Canada. This allows to estimate threshold values above which one payment method becomes more costly than the other for the consumer.

Only a few studies attempt to also integrate the benefits of payment instruments. “Benefit” in this case means that other useful services are provided in addition to pure payment processing. These are, for example,

Most of the benefit categories relate to cashless payments. However, “data protection, protection of privacy” is a particular benefit of cash (in contrast, data collection represents a cost of non-cash payments). The first exemplary experiments in this respect can be found in Garcia-Swartz et al. (2006a, b), who try to estimate the marginal benefit (in monetary units) of “privacy” for consumers. The benefit of anonymity of cash payments and the protection of privacy is measured by the discounts granted under loyalty card programs (“loyalty card discounts”). According to the authors, these represent the implicit benefit of disclosing private information. Knümann et al. (2024, section 3.2.4) go one step further to quantify this effect. On the one hand, they evaluate questions on the willingness to pay for the deletion of data generated during a standard card payment as part of a survey on payment behavior. On the other hand, they refer to the bonuses within the German Payback program. Taking the average of both approaches, Knümann et al. (2024) calculate that the costs of data disclosure account for almost 60% of the total costs for debit cards and around one third for credit cards.

Distributional aspects and socio-economic differences are additional factors to be taken into account. Felt et al. (2021) quantify the private costs (net) incurred by consumers for the use of cash, credit cards and debit cards for the USA and Canada for various income classes. The net costs considered include bank fees (card and account maintenance fees, cash withdrawal fees), reward programs from credit or debit card companies, and merchant costs of accepting payment instruments, which are reflected in higher consumer prices. The authors find that credit card transactions are cross-subsidized by cheaper debit cards and cash payments. Of the three types of costs, the (non-transparent) pass-through to consumer prices represents the largest block for consumers. Measured in terms of the respective transaction value, consumers in the lowest income bracket bear the highest net costs, while those in the highest income cohort bear the lowest. The pricing of means of payment and the passing on of means of payment costs to (payment means independent) sales prices therefore have regressive distributional effects.

Estimating the costs of different payment instruments for consumers on a comparable and harmonized basis is a challenging task. There is considerable scope for discretion, particularly when recording and evaluating time, estimating data disclosure costs and with respect to pricing. Costs are important, but ultimately a broader cost-benefit analysis must be carried out. In a market economy, the focus should be on consumers as long as they have complete freedom of choice. Consumers react to price signals and changes in cost-benefit ratios. However, preferences also matter and a clear and convincing price signal must be given to trigger a change in the choice of payment instruments. Overall, there should be cost transparency for consumers when it comes to payment methods. A well-functioning payment infrastructure in terms of acceptance of, access to and affordability of means of payment and an efficient payment cycle are expedient in this context. This is not least the task of central banks and governments, as a functioning and cost-efficient payment system is an essential infrastructure, just like the water and electricity supply.

Carbo-Valverde, S. & F. Rodriguez-Fernandez (2019), An International Approach to the Cost of Payment Instruments: The case of cash, May.

Felt, M.-H., F. Hayashi, J. Stavins & A. Welte (2021), Distributional Effects of Payment Card Pricing and Merchant Cost Pass-through in Canada and the United States, Bank of Canada, Staff Working Paper 2021-8, February.

Garcia-Swartz, D. D., R.W. Hahn, & A. Layne-Farrar (2006a), The Move Toward a Cashless Society: A Closer Look at Payment Instrument Economics, Review of Network Economics 5, 175-197.

Garcia-Swartz, D. D., R.W. Hahn, & A. Layne-Farrar (2006b), The Move Toward a Cashless Society: Calculating the Costs and Benefits, Review of Network Economics 5, 198-228.

Knümann, F., M. Krueger & F. Seitz (2024), Costs and Benefits of Cash and Cashless Payment Instruments – Module 3: Costs of cash and card payments from a consumer perspective, study commissioned by the Deutsche Bundesbank.

Kosse, A., H. Chen, M.-H. Felt, V. Dongmo Jiongo, K. Nield & A. Welte (2017), The Costs of Point-of-Sale Payments in Canada, Bank of Canada, Staff Discussion Paper 2017-4, March.

Krueger, M. & F. Seitz (2025), Costs of Means of Payment for Consumers: Literature review and some sensitivity analyses, IMFS Working Paper Series No. 218, March.

Sveriges Riksbank (2023), Cost of Payments in Sweden, Riksbank Studies, NR 1 2023, March.

Trütsch, T., J. Huber & N. Bralovic (2024), The Cost of Point-of-Sale Payments in Switzerland, University of St. Gallen.

For more details and different cost concepts see Krueger & Seitz (2025).

In the EU and with the European Directive on Digital Content and Services, the costs in the form of data disclosure by consumers are legally equivalent to a payment.

The cost advantage of cash is understated, as the cash costs in this study relate to an average ATM transaction. As larger amounts are withdrawn at ATMs, these costs are spread over several payment transactions.

The high value of 30.9 % for Hungary is an outlier. The second-highest value is only 3.13 %.