This policy brief is based on ECB Working Paper Series, No 3108. This paper should not be reported as representing the views of the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Deutsche Bundesbank. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB and the Deutsche Bundesbank.

Abstract

In contrast to the conventional Fisherian view that inflation can directly support financial stability by reducing real debt positions, we show that significant increases in inflation are strongly associated with financial crises. In the spirit of Jorda et al. (2020), countries with free and fixed exchange rates can be compared to difference out the confounding reaction of monetary policy. Across a dataset of 18 advanced economies over 151 years, we show that the impact of inflation extends beyond its indirect effect via monetary policy, already documented in the literature. To further corroborate causality, we instrument inflation with oil supply shocks, finding that a 1 percentage point rise in inflation doubles the probability of financial crisis from its sample average. We give evidence for the redistribution channel, where inflationary shocks directly cut real incomes, as a possible mechanism. In conjunction with recent literature on the dangers of rapidly tightening monetary policy, our results point to a difficult trade-off for central banks once inflation has risen.

The year 2022 saw the beginning of a rapid change in monetary policy around the world. This renewed an interest in the trade-off between rising interest rates and financial stability. New research began to unearth a pattern of interest rates that was particularly destabilising, that is, rates rising after a period of low or declining rates. Such a pattern has been proven to facilitate an unravelling of previously built-up financial vulnerabilities and therefore typifies many financial crises throughout history (Schularick et al., 2021; Jimenez et al., 2023).

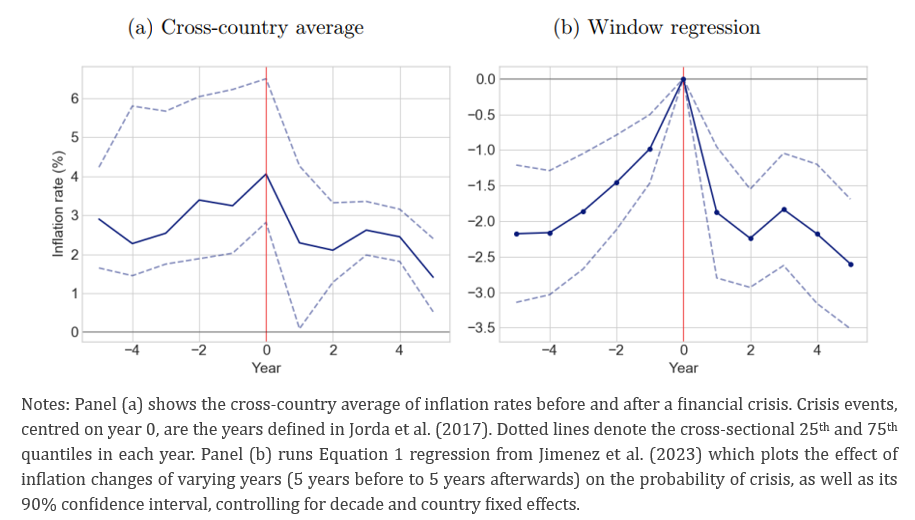

However, interest rate hikes are usually a central bank response to inflationary pressures. Indeed, the average inflation rate tends to rise in the years preceding a crisis (Figure 1, Panel a). A replication of reduced-form regressions in the spirit of Jimenez et al. (2023) and looking at inflation illustrates this result more formally (Figure 1, Panel b). This raises an important question: does inflation itself undermine financial stability, or is it merely a trigger for the monetary tightening that follows?

Figure 1. Inflation around financial crises – post- WWII

This research sheds light on these crucial aspects by providing novel evidence for the causal effects of inflation on financial instability. To do this, we make use of the Jorda-Schularick-Taylor Macrohistory Database (Jorda et al., 2017), which combines many different historical sources to form a continuous, annual record of macro-finance from 1870 to 2020 for 18 advanced economies.

From a theoretical standpoint, one significant channel through which high inflation contributes to financial instability is its pronounced adverse redistributive repercussions (Auclert, 2019). According to this perspective, inflationary shocks can create financial vulnerabilities for households by reducing real income through the so-called inflation tax. This income erosion hampers households’ ability to meet debt obligations, particularly affecting the poorest groups, whose consumption is more sensitive to income changes due to the larger share of basic necessities in their consumption basket. As a result, these households may struggle financially until their incomes gradually recover through second-round effects.

Another hypothesis we can consider involves the credibility of central banks. In the aftermath of significant inflation surges, the risk of inflation spiralling out of control and leading to a full-fledged de-anchoring of expectations becomes tangible, particularly if the central bank lacks strong credibility (Blinder, 2000). When inflation expectations become de-anchored, the effectiveness of monetary policy interventions is severely affected. This can also undermine the central bank’s ability to fulfil its critical role as the ‘lender of last resort’, as bank runs might swiftly escalate into runs on the domestic currency (Kaminsky & Reinhart, 1999). Consequently, the economy is left without a crucial financial stability backstop (Freixas et al., 1999; Robatto, 2019; Albertazzi et al., 2022).

Identifying the causal effect of inflation on financial stability is challenging because inflation and interest rate changes usually occur together. To control for this indirect effect we exploit that, under certain conditions, countries are forced to track the monetary policy of another country. The monetary policy reaction from an inflationary shock should therefore be experienced across multiple countries. By comparing countries with differing inflation outlooks but the same monetary policy, we can gauge the causal effect of inflation on financial stability.

The results show a clear pattern: rising inflation significantly increases the probability of financial crises, even for given monetary policy. A further analysis distinguishes between inflation driven by supply shocks (for instance, energy price surges) and demand shocks (strong spending, financial exuberance). Both types of inflation episodes are associated with heightened financial risk. The study also uses oil supply shocks as an instrument variable to further verify causality.

Finally, the effects vary across countries. An interesting result is that inflationary shocks appear more dangerous in episodes where the mortgage-to-GDP ratio is elevated and wage growth is low. Other factors, such as central bank independence and the fragility bank-funding, also tend to amplify the impact, albeit to a lesser extent. This heterogeneity is indicative of the prevailing mechanisms explaining the existence of a direct link between inflation and financial stability.

These results complement the Fisherian view that inflation can help reduce debt burdens through debt deflation (Brunnermeier et al (2025)), suggesting that the Fisherian and benign effects taking place at the micro-level are accompanied by systemic adverse mechanisms.

In terms of policy implications, our findings, together with those available from the related literature, indicate that both higher inflation and higher rates are detrimental to financial stability. This raises the question of what effect might dominate. Comparing estimates from Jimenez et al. (2023) and Schularick et al. (2021), both based on the same dataset as this paper, offers some insights. To make our results directly comparable with Jiménez et al. (2023), we define a financial crisis as one occurring within the next 3 years. Under this definition, our estimates show that a 1 percentage point rise in inflation increases the probability of a financial crisis within 3 years by about 7 percentage points. To put this into perspective, we can compare the effect of inflation with that of an interest rate hike large enough to offset it. According to existing research, such as Schularick and Taylor (2012), countering a 1 percentage point rise in inflation would typically require roughly a 1 percentage point rate increase. Jiménez et al. (2023) suggests that this rate hike would raise the probability of a crisis by about 7 percentage points if it followed a long period of low or declining rates, and by about 3 percentage points otherwise.

Taken together, these findings imply that letting inflation rise can be more damaging for financial stability than the raise in rates to contain it and that it tends to be equally damaging when the rate increase follows an extended phase of monetary easing that has already fuelled financial imbalances. In such cases, the risks of acting or not acting may be broadly balanced. Central banks therefore may face tough trade-offs when strong inflationary pressures emerge after years of very low or declining interest rates. Overall, this analysis once again confirms the importance of a resilient banking sector, as is currently the case in the European Union (Buch, 2025), for both financial stability and monetary policy.

Albertazzi, U., Burlon, L., Jankauskas, T., & Pavanini, N. (2022). The shadow value of unconventional monetary policy. CEPR Discussion Paper (DP17053).

Auclert, A. (2019). Monetary policy and the redistribution channel. American Economic Review, 109(6), 2333–2367.

Blinder, A. S. (2000). Central-bank credibility: Why do we care? how do we build it? American economic review, 90(5), 1421–1431.

Brunnermeier, M, S. Correia, S. Luck, E. Verner, and T. Zimmermann (2025). The Debt-Inflation Channel of the German (Hyper) Inflation. The American Economic Review, 115(7), 2111–50.

Buch, C. (2025). Stress tests in uncertain times: assessing banks’ resilience to external shocks. European Central bank, The Supervision Blog.

Freixas, X., C. Giannini, G. Hoggarth & F. Soussa. (1999). Lender of last resort. Financial Stability Review, November.

Jimènez, G., Kuvshinov, D., Peydró, J.-L., & Richter, B. (2023). Monetary policy, inflation, and crises: Evidence from history and administrative data, forthcoming Journal of Finance.

Jordà, O., Schularick, M., & Taylor, A. M. (2017). Macrofinancial history and the new business cycle facts. NBER macroeconomics annual, 31(1), 213–263.

Kaminsky, G. L., & Reinhart, C. M. (1999). The twin crises: the causes of banking and balance-of-payments problems. American economic review, 89(3), 473–500.

Robatto, R. (2019). Systemic banking panics, liquidity risk, and monetary policy. Review of Economic Dynamics, 34, 20-42.

Schularick, M., Steege, L. t., & Ward, F. (2021). Leaning against the wind and crisis risk. American Economic Review: Insights, 3(2), 199–214.

Schularick, M., & Taylor, A. M. (2012). Credit booms gone bust: monetary policy, leverage cycles, and financial crises, 1870–2008. American Economic Review, 102(2), 10291061.