The views expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), its Executive Board, IMF management, or the Central Bank of Ireland. Any remaining errors are the authors’ sole responsibility. Affiliations are for identification purposes only.

Abstract

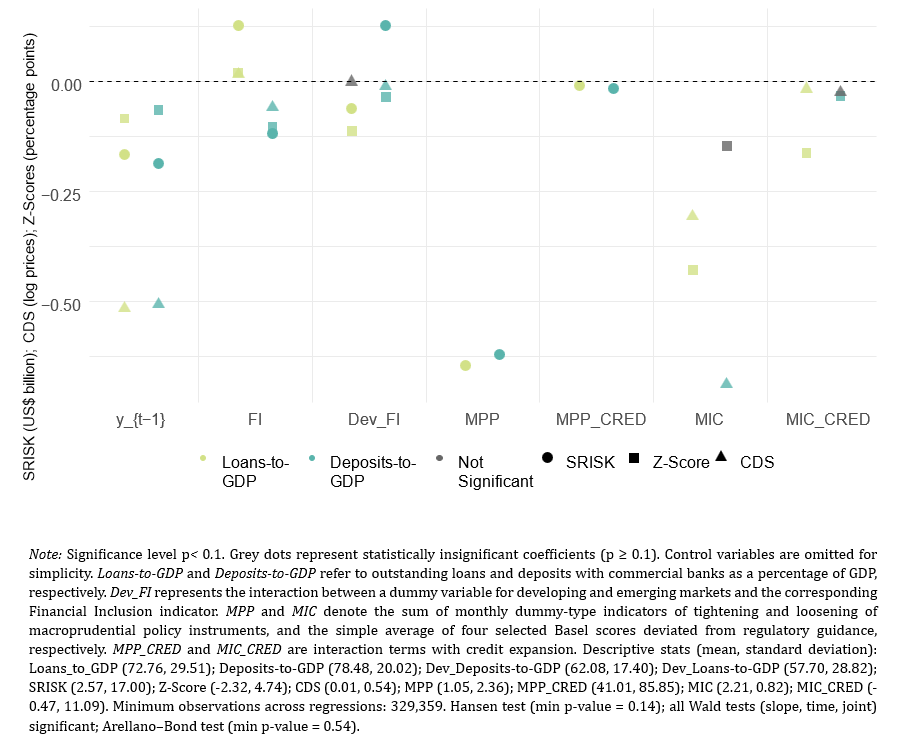

Financial inclusion (FI) can support stability by broadening access to formal finance, yet it may also increase systemic vulnerabilities when expansion is concentrated or accompanied by looser lending standards. Using bank-level data for 574 commercial banks across 31 countries during 2009–2021, Naceur et al., 2024 examine how different dimensions of FI relate to both systemic risk (SRISK) and idiosyncratic risk (Z-Score and CDS). Three robust messages emerge. First, credit inclusion measured as borrowers per adult is associated with lower systemic and idiosyncratic risks, consistent with diversification through reaching new, previously underserved clients. Second, credit expansion measured as loans-to-GDP correlates with higher risks, indicating that volume growth without dispersion may mask concentration. Third, when tighter macroprudential policy (MPP) and stronger Basel compliance accompany credit expansions, they mitigate these effects. Finally, we observe that the advancement of non-banks in the provision of financial services raises risks for the banking sector.

Policy debates commonly emphasize the benefits of financial inclusion, yet its effects on stability are not always straightforward. The literature, however, suggests heterogeneous effects depending on the service type (loans versus deposits), providers (banks versus non-banks), and the prudential environment. Deposit inclusion can stabilize funding by mobilizing small, persistent balances, whereas rapid credit growth under competition can erode credit standards. In emerging and developing economies, fewer opportunities for asset diversification may dilute the stabilizing role of deposits at the systemic level. At the same time, growth of non-bank credit intermediation intensifies competitive pressure on banks and may shift risks outside the core regulatory perimeter.

We assemble a panel covering 574 listed commercial banks in 31 advanced and emerging economies from 2009 to 2021. Systemic risk is proxied by SRISK (Brownlees and Engle, 2017), while idiosyncratic risk is captured by the bank Z-Score (signed-reversed) and the firm-specific idiosyncratic component of CDS spreads. FI is proxied using two complementary dimensions: the share of outstanding loans and deposits in GDP, which captures financial deepening, and the number of borrowers and depositors per 1,000 adults, which captures the breadth of participation. To address competitive dynamics, we also include the market share of non-banks in loan and deposit provision.

We estimate dynamic specifications with bank and time fixed effects using Arellano–Bond GMM, controlling for bank fundamentals (size, ROA, equity), macro conditions (GDP growth, portfolio equity flows, deposit rates, stock volatility), and prudential stances: country-level macroprudential tightening and bank-level Basel III compliance, including interactions with credit expansions to capture policy synchronization.

Credit inclusion that raises the number of borrowers per adult lowers both systemic and idiosyncratic risks, supporting the diversification channel. By contrast, higher loans-to-GDP is associated with greater risks, consistent with concentration dynamics. Deposit inclusion generally reduces risks, but in developing economies the effect on SRISK is weaker or can even reverse when banks lack asset diversification opportunities. A higher market share of non-banks in either lending or deposit services raises banks’ systemic and idiosyncratic risks, pointing to competitive pressures and potential regulatory arbitrage. Macroprudential tightening and stronger Basel compliance are independently stabilizing; critically, when these prudential tools are synchronized with phases of FI-driven credit growth, the risk-reducing effect is amplified.

Policy should steer FI toward diversifying credit access rather than merely expanding aggregate loan volumes. Monitoring loans-to-GDP alone is insufficient; supervisors should track the dispersion of borrowers and concentration by sector and borrower type. Where deposit inclusion grows quickly, especially in developing economies, banks should pair it with asset-side diversification. Authorities should ensure that non-banks are subject to proportional regulatory standards, so that risks do not migrate outside the regulated banking sector. Finally, macroprudential cycles should be explicitly linked to FI dynamics, tightening when credit inclusion accelerates in ways that could relax standards, and recognizing that synchronized Basel compliance at the bank level strengthens system-wide resilience.

Figure 1. Estimated Coefficients and Significance Levels

Brownlees, C., & Engle, R. F. (2017). Srisk: A conditional capital shortfall measure of systemic risk. The Review of Financial Studies, 30 (1), 48–79.

Ben Naceur, S.., Candelon, B., & Mugrabi, F. (2024). Systemic implications of financial inclusion. International Monetary Fund.