This policy brief is based on Bank of Finland Research Discussion Papers, No. 9/2024. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

Policymakers face significant uncertainty when implementing countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) rules. Different models often provide conflicting guidance, and relying on a single framework may result in policy errors. Using twelve state-of-the-art Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models with banking frictions, we identify CCyB rules that perform well across models. These robust rules suggest only moderate increases in capital buffers of around 10–20 basis points for a one-percentage-point increase in the credit-to-GDP ratio. This cautious approach balances financial stability with growth while reducing risks from model uncertainty. Our findings can guide policymakers in implementing macroprudential policy: robust CCyB rules exist, and they favor prudence over activism.

Introduced under Basel III, countercyclical capital buffers strengthen the resilience of the banking sector by requiring banks to build additional capital during credit booms. These buffers can then be released during economic downturns, thereby dampening the financial cycle and limiting spillovers to the real economy. Despite their importance, policymakers face challenges in calibrating the buffers. Academic studies propose a wide range of approaches, often with conflicting recommendations. Without a benchmark model for macroprudential policy, authorities must make decisions amid considerable uncertainty. The key question is how to design effective rules when it is unclear which model best represents economic reality.

To address this challenge, we employ twelve modern DSGE models featuring banking frictions. These models differ in their representation of financial intermediation, featuring monopolistic competition, costly state verification, or moral hazard. Our model suite covers both closed and open economies. In our analysis, the macroprudential authority is assumed to prioritize financial stability, macroeconomic stability, and smooth policy implementation. We model the CCyB as a simple rule responding to the credit-to-GDP gap.

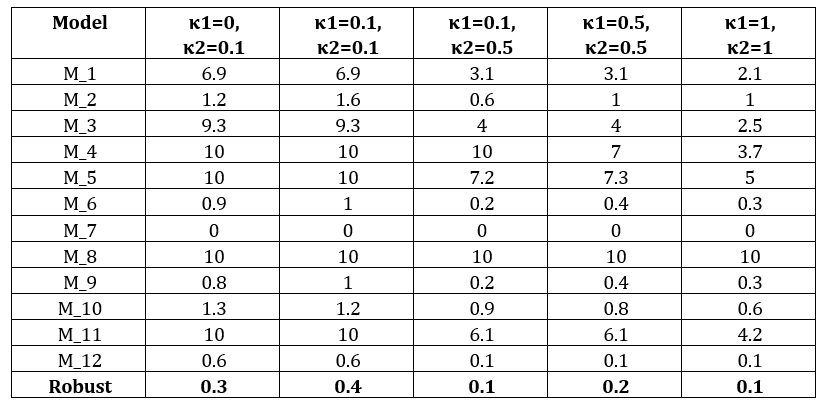

For each model, we compute the optimal CCyB response and then identify rules that perform well across all models. This mirrors the real-world dilemma of policymakers, who must act without knowing which (if any) of these models is the most accurate. Table 1 reports the results.

Table 1. Optimized model-specific and model-robust φccyb coefficients

Note: The table reports the optimized model-specific φccyb coefficients for models M_1–M_12, and the model-robust coefficients in the last row, for different loss functions of the macroprudential authority. All loss functions stabilize the volatility of credit-to-output with a unit weight. κ1 refers to the weight attached to stabilizing output volatility and κ2 the weight attached to stabilizing volatility of the policy instrument.

Our results consistently point toward moderation. Across the models, robust rules recommend only small increases in the capital buffer, typically 10–20 basis points for each one-percentage-point deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from its steady state. While larger responses may be beneficial in some models, they can prove destabilizing in others. The broader the set of models considered, the more cautious the robust response becomes, reflecting the principle that greater model uncertainty calls for greater prudence.

Importantly, the cost of insuring against model uncertainty is relatively low. Although the robust rule is rarely the optimum of a single model, it performs adequately across all models. The additional volatility from adopting a cautious rule is modest and falls within the range considered acceptable in related monetary policy debates. Even when interest-rate shocks drive the cycle, robust CCyB rules remain effective and cautious.

The message is clear: countercyclical buffers should be adjusted prudently rather than aggressively. Small, steady increases in capital requirements strengthen resilience without unnecessarily constraining credit. Policymakers do not need to identify the “true” model to act effectively; robust rules provide reliable guidance, even under considerable uncertainty. In short, prudence, not activism, is the path to macro-financial stability.