The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Italy or the Eurosystem. This policy brief is based on Bank of Italy, Occasional Paper No 974.

Abstract

This policy brief reviews recent evidence on how geopolitical tensions and political divides affect cross-border capital flows. Geopolitical risk systematically reduces flows across asset classes, with the sharpest effects on those towards emerging economies. Political alignment also matters and increasingly shapes the geography of international investment, with signs of bloc-based allocations, especially in strategic sectors and, to some extent, in Europe after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These findings underscore the growing influence of geopolitics on global finance and raise important policy and research questions about the implications of fragmentation for macroeconomic and financial stability.

Recent geopolitical developments—including the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the resulting sanctions on Russia, the conflict in the Middle East, and rising trade frictions following President Trump’s announcement of “reciprocal tariffs”—have renewed concerns about the economic consequences of geopolitics. A central question is whether strategic policy choices may reverse decades of economic integration, leading to what Aiyar et al. (2023) define geoconomic fragmentation. In financial markets, this fragmentation would imply that countries increasingly lend and borrow within politically aligned blocs, reducing exposure to rival ones (Bianchi and Sosa-Padilla, 2023). Understanding how geopolitics reshapes capital flows is therefore essential for policymakers seeking to preserve financial stability, safeguard market integration, and anticipate structural shifts in the global financial architecture.

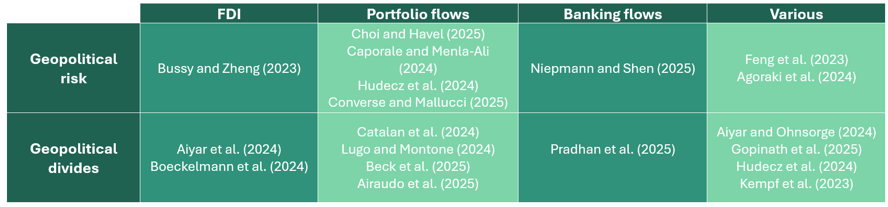

In Albori (2025), I survey the fast-growing literature on the fragmentation of international capital flows, distinguishing between the effects of geopolitical risk shocks and more persistent geopolitical divides rooted in political alignment (Table 1).1 Although often analysed separately, these phenomena are deeply intertwined. Rising diplomatic tensions can escalate into threats, sanctions, or conflict—shocks that raise geopolitical risk—while also deepening long-term ideological divides that underpin geoeconomic decoupling.2 The tools upon which empirical works rely reflect this distinction. Geopolitical risk is typically measured using the news-based index developed by Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) – which captures the share of articles reporting adverse geopolitical events or related threats. Political similarity between countries is instead proxied by the Ideal Point Distance (Bailey et al., 2017), derived from voting patterns in the United Nations General Assembly and used either directly as a regressor or to classify countries into geopolitical blocs according to their relative alignment with the United States or China.

The empirical evidence shows that geopolitical risk dampens all major forms of cross-border capital flows—foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio investment, and bank lending. Higher geopolitical risk raises the likelihood of adverse events such as sanctions, expropriations, or disruptions to trade and payments systems, lowering expected returns and increasing uncertainty. As a result, shocks to geopolitical risk systematically trigger retrenchment and flight-to-safety dynamics, with investors withdrawing from riskier countries in response to both global and country-specific shocks, looking for safer destinations. The deterring effect is significant not only for more volatile flows like portfolio investment and bank loans but also for FDI, given the sunk costs and long-term horizons involved. Emerging market economies tend to be more exposed, though strong institutions and sound governance are shown to mitigate the negative impact of heightened risk. Moreover, the effects of geopolitical risk spill over regionally: when geopolitical risk rises in one emerging market, investors also withdraw from neighbouring countries, mirroring the contagion patterns observed after natural disasters and documented in Ferriani et al.(2023).

Geopolitical risk also interacts with and amplifies other global shocks, increasing the risk of weaker capital inflows. It strengthens the negative effect of economic policy uncertainty on fund investments (Agoraki et al., 2024), magnifies monetary policy tightening (Pradhan et al., 2025), and intensifies the transmission of the global financial cycle via political ties (Ambrocio et al., 2024).

Beyond short-term retrenchment, political alignment influences the structural allocation of international capital. Recent evidence suggests an increasing role of ideological distance in shaping cross-border investment across asset classes. This tendency has strengthened since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the more so in European investment, particularly FDIs. Importantly, these patterns are not limited to a few expected bilateral relationships involving geopolitical contenders like Russia, China, or major Western economies, but instead reflect a broader, systemic shift.

The effect is more pronounced when the investment is in a strategic sector, stressing how national security concerns, and the policies they inform, are relevant determinants of cross-border investment decisions.

As with the immediate retrenchment triggered by geopolitical risk, emerging market economies appear more sensitive to fragmentation dynamics. Institutional quality partly mitigates the impact on portfolio positions, yet these countries are generally more vulnerable due to their greater misalignment between the geopolitical stance and creditor composition (Aiyar and Ohnsorge, 2024). A cross-border investment diversion effect also appears to be at play: a recipient country may experience higher inflows when geopolitical distance increases between its source countries and their other financial partners.

Crucially, political distance matters well beyond episodes of acute tension. Even in tranquil periods, ideological proximity shapes capital allocation decisions: it influences cross-border bank lending and fund investments (Kempf et al., 2023), is associated with stronger and more persistent spillovers from US financial volatility to stock market returns in non-OECD economies (Ambrocio et al., 2024), particularly in those where political alignment with major powers (the US, EU, and China) is more unbalanced. Again, this finding echo broader evidence of emerging markets’ heightened sensitivity to geopolitical factors. Finally, geopolitical divides could be amplified by local narratives shaped by domestic media (Agarwal et al., 2024).

Table 1. Papers on the effects of geopolitical risks and divides on capital flows

The evidence consistently shows that geopolitical tensions and political divides concur to shape the direction and size of cross-border capital flows. Geopolitical risk induces broad retrenchment and flight-to-safety dynamics, with emerging market economies particularly exposed both to direct and contagion effects. Moreover, geopolitical risk interacts with other economic forces, such as monetary policy and economic uncertainty, amplifying their transmission across borders. At the same time, rising geopolitical divides influence the allocation of international capital, affecting all kinds of cross-border investment, with a tendency toward bloc-based investment patterns. While the two strands of the literature have generally treated geopolitical shocks and ideological distance separately, they may be capturing responses to similar underlying shifts in international relations.

As in other works on capital flows, the role of offshore financial centres is a challenge. Better identifying the true source and destination of cross-border positions remains essential to determine whether observed reallocations reflect genuine shifts in financial relationships or simply the use of intermediating jurisdictions.

Looking ahead, several broader, interrelated, and crucial questions for policy makers remain open. Do trade and financial fragmentation evolve jointly or along separate lines? What are the macroeconomic consequences of financial fragmentation? And how might a more polarized world reshape the role of reserve currencies and the demand for safe assets?

Agarwal, I., W. Chen, and E. S. Prasad (2024): “Beyond the Fundamentals: How Media-Driven Narratives Influence Cross-Border Capital Flows”, NBER Working Papers 33159.

Ambrocio, G., I. Hasan, and X. Li (2024): “Global political ties and the global financial cycle”, Bank of Finland Research Discussion Papers 1/2024, Bank of Finland.

Agoraki, M.-E. K., H. Wu, T. Xu, and M. Yang (2024): “Money never sleeps: Capital flows under global risk and uncertainty”, Journal of International Money and Finance, 141.

Aiyar, M. S., M. J. Chen, M. C. H. Ebeke, M. R. Garcia-Saltos, T. Gudmundsson, M. A. Ilyina, M. A. Kangur, T. Kunaratskul, M. S. L.

Rodriguez, M. Ruta, T. Schulze, G. Soderberg, and J.P. Trevino (2023): “Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism”, IMF Staff Discussion Notes 2023/001, International Monetary Fund.

Aiyar, S. and F. Ohnsorge (2024): “Geoeconomic Fragmentation and Connector Countries”, MPRA Paper 121726.

Airaudo, F., F. De Soyres, K. Richards, and A. M. Santacreu (2025): “Measuring Geopolitical Fragmentation: Implications for Trade, Financial Flows, and Economic Policy”, Working Papers 2025-006, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Albori M. (2025), “Politics will tear us apart, again. Geopolitical risk, fragmentation, and capital flows“, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers) 974, Bank of Italy.

Bailey, M. A., A. Strezhnev, and E. Voeten (2017): “Estimating Dynamic State Preferences from United Nations Voting Data”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61, 430–456.

Bianchi, J. and C. Sosa-Padilla (2023): “The Macroeconomic Consequences of International Financial Sanctions”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, 113, 29–32.

Caldara, D. and M. Iacoviello (2022): “Measuring Geopolitical Risk”, American Economic Review, 112, 1194–1225.

Converse, N. and E. Mallucci (2025): “Geopolitical Risk: When it Matters; Where it Matters. Evidence from International Portfolio Allocations”.

Ferriani, F., A. Gazzani, and F. Natoli (2023): “Flight to climatic safety: local natural disasters and global portfolio flows”, Temi di discussione (Economic working papers) 1420, Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area.

Kempf, E., M. Luo, L. Schäfer, and M. Tsoutsoura (2023): “Political ideology and international capital allocation”, Journal of Financial Economics, 148, 150–173.

Pradhan, S.-K., V. Stebunovs, E. Takáts, and J. Temesvary (2025): “Geopolitics Meets Monetary Policy: Decoding Their Impact on Cross-Border Bank Lending”, International Finance Discussion Papers 1403, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

For the complete list of references upon which the review draws from, see the Bibliography in my work. The following sections summarize their findings without direct reference to each individual contribution.

Converse and Mallucci (2025) is a notable exception as, in the context of exploring the effects of geopolitical risk on funds allocations, it shows how shock-induced shifts in portfolio compositions may lead to fragmentation.