Although monetary policy rates have increased rapidly in recent quarters, in response to the rise in energy prices and inflation, it can be expected that price stability will be restored in the medium term. At that point, monetary policy rates will return to their neutral level – the level consistent with stable inflation and the real rates at their long-run, natural level. Empirical estimates suggest that the long-run natural rate has drifted towards values close to zero in recent decades, and is expected to remain low for quite some time. For example, Holston et al. (2017) finds that, in 2016, the long-run natural rate was around 0.5% in the US and possibly slightly negative in the Euro Area. The future evolution of the long-run natural rate is also uncertain. Platzer and Peruffo (2022) forecast the natural rate in the US to reach a trough of 0.38% by 2030, and then rise again to 1% in the very long run. How is the neutral policy rate affected by the expected, low value of the long-run natural rate, given the zero lower bound on nominal rates? What is the optimal conduct of monetary policy in view of the prevailing uncertainty as to the future level of the long-run natural rate?

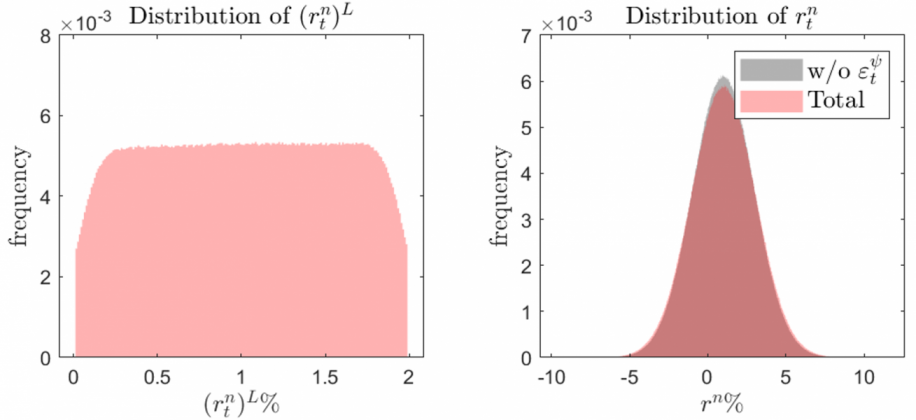

Compared to the benchmark new Keynesian model, four new parameters emerge: the boundaries and the standard deviation of shocks to the trend productivity growth rate, and the convenience yield on treasuries. For the productivity trend growth rate, we set the value range between 1% and 3% and the standard deviation of shocks to about one tenth that of transitory real rate shocks. This reflects both the value range that we obtain for the US economy and the value range that Holston et al. (2017) obtain for the Euro Area. The standard deviation is based on the estimate in Fiorentini et al. (2018), which uses historical data for a set of 17 economies. Finally, the subjective discount factor and the convenience yield are calibrated so as to replicate the features of the long-run natural rate in recent years, i.e., to drift towards values around zero. For the convenience yield on treasuries, we follow Del Negro et al. (2017), which finds that it might have reached 3% in the US in 2016. For the subjective discount factor, we follow Platzer and Peruffo (2022) which forecasts a natural rate of 1% in the US in the very long run.

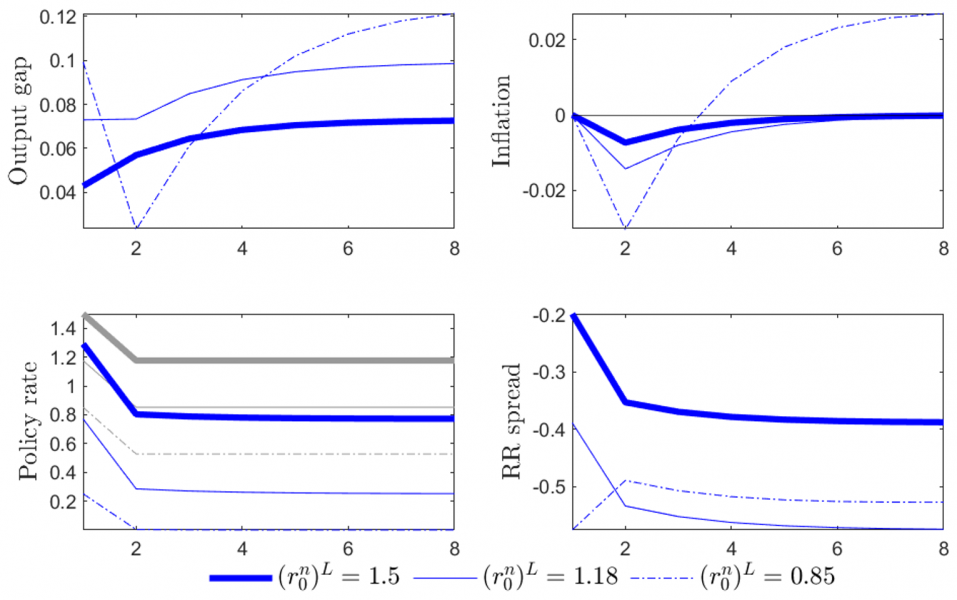

Outcomes change for lower initial values of the long-run natural rate. Figure 2 illustrates the case when this is equal to 0.85% and the initial value of the neutral rate is slightly larger than 0.2%. The policy reaction described above is no longer feasible due to the lower bound. In the new risky steady state, the neutral rate reaches zero, but this amount of easing is insufficient to offset the deflationary bias in expectations. The central banker mitigates the deflationary bias by committing to create inflation and an output boom in reaction to future positive shocks. This promise exerts an expansionary effect on both actual output (IS curve) and actual inflation (Phillips curve) and translates into positive actual inflation.

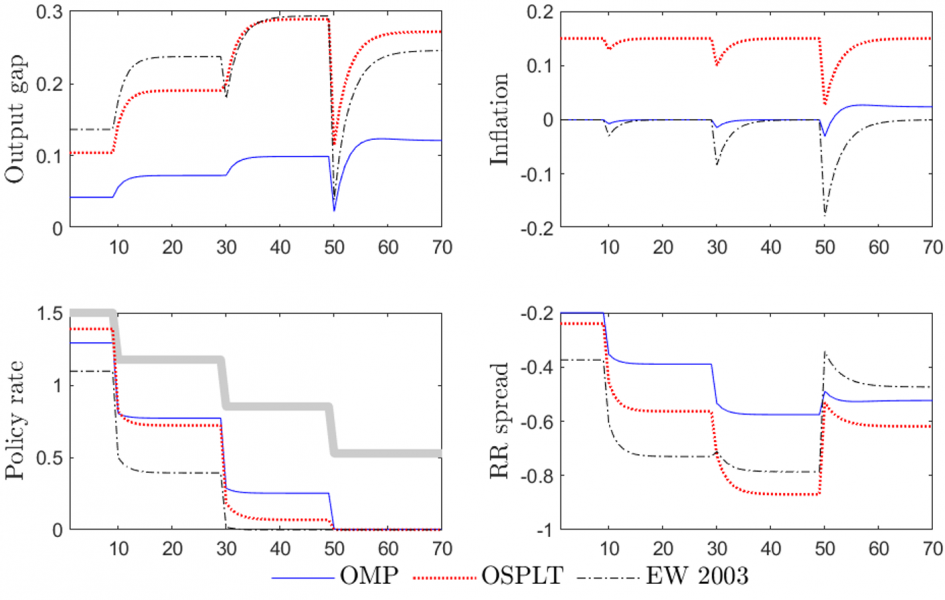

Figure 4 displays impulse responses to a sequence of three large negative permanent shocks to the long-run natural rate, which bring it from 1.5% to 0.5%, under optimal policy (blue), the constant price level targeting rule of Eggertsson and Woodford (black dotted line), and the optimal simple price level targeting rule (red). It shows that the neutral policy rate reaches zero earlier under price level targeting than under optimal policy. For the constant price level targeting rule, this is the case already when the long-run natural rate falls below 1%. This is due to the fact that simple rules are less sophisticated than optimal policy in their ability to manage expectations in reaction to adverse shocks. When the economy contracts and the GAPL undershoots the target, optimal policy prescribes to increase the target by an amount proportionate to the actual target shortfall, which commits the central bank to conduct a more expansionary policy in the future than what is needed to undo deflation. By contrast, under simple rules, the target is exogenous. A constant target for example would commit the central bank to “just” undo deflation. This policy is less effective in mitigating economic contractions. For a given value of the long-run natural rate, the negative skew in expectations induced by the ZLB constraint is therefore larger, the output gap needed to offset the deflationary bias in inflation expectations is higher, and the neutral policy rate is lower.

The euro area experience has demonstrated that the effective lower bound on nominal interest rates is not zero, but somewhat negative due to cash storage costs. We abstract from this feature in our simple model.