Labor productivity, measured as output per hour worked, is more procyclical in countries with lower employment volatility. To capture this new stylized fact, we propose a business cycle model with employment adjustment costs, variable hours per worker and labor effort. We show that variations in work effort help to replicate the procyclicality of labor productivity observed in many OECD countries. In contrast, the constant-effort model fails to replicate the observed cross-country pattern in the data. By implication, labor market deregulation – a reduction in firms’ employment adjustment costs – reduces the cyclicality of labor productivity by more when effort can vary. Variable effort is thus relevant for evaluating the effect of such a reform. More fundamentally, we argue that the cyclicality of labor productivity in itself is not a reliable indicator of which type of shock – technology or demand – drives the business cycle.

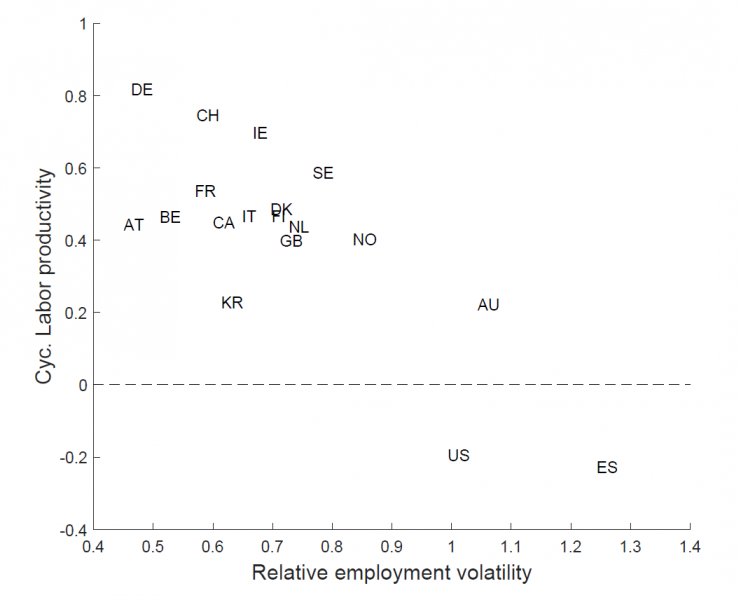

Using data from 1984 to 2019, Figure 1 shows that countries with lower employment volatility are characterized by more procyclical labor productivity, that is, by a higher correlation between output and measured labor productivity (i.e. output per hour worked).

Figure 1: Relative employment volatility and cyclicality of labor productivity

Notes: Sample period 1984q1-2019q4. Labor productivity measured as quarterly real output per hour. Employment volatility measured relative to output. Cyclical component of log productivity, log employment and log output extracted with HP filter (Hodrick and Prescott, 1997). Volatility measured as standard deviation, cyclicality measured as correlation between cyclical components of output and labor productivity. Data sources: OECD, Eurostat, Ohanian and Raffo (2012), ILO, National Offices of Statistics.

This pattern holds also for the Great Recession period 2008 to 2013, which is widely believed to have been driven by deficient demand. Replacing employment volatility with unemployment volatility does not alter our key empirical message, suggesting that the participation margin does not play a large role for the stylized fact shown here.

Economic models struggle to explain the procyclicality of labor productivity when demand shocks are important drivers of business cycles. This is because those shocks lead to countercyclical movements in labor productivity, while technology (or supply-side) shocks give rise to a comovement of output and labor productivity.

First, a natural candidate explanation for the pattern in Figure 1 is that technology shocks are the dominant source of business cycle fluctuations in countries with highly procyclical productivity, while demand shocks are more important in countries where the cyclicality of labor productivity is low. This is consistent with employment being rather stable in the former group of countries, and more variable in the latter. However, the Great Recession was a large shock that hit several countries simultaneously and, arguably, in similar ways. This suggests that the large cross-country variation in business cycle moments shown in Figure 1 can be traced to structural differences across economies, which in turn led to differences in shock transmission, rather than the shock mix itself being idiosyncratic.

Second, the Great Recession is widely believed to have been driven by deficient demand, see for instance Christiano et al. (2015). In a demand-driven recession, a drop in labor productivity is difficult to explain with standard business cycle models in the absence of variable factor utilization. With unchanged technology, we expect firms to cut back their labor input as demand for their products declines. Labor productivity goes down only if labor falls by less than output. With capital fixed in the short run, this means that labor is utilized less intensively – i.e. effort falls – during the downturn. Variable capital utilization as in Christiano et al (2005) could, as an alternative model feature, generate procyclical labor productivity without the necessity to endogenize labor effort. However, Lewis et al (2019) show that effort clearly outperforms capital utilization in terms of explaining the Euro Area business cycle.

In Dossche et al (2021), our aim is thus to develop a model that can replicate the evidence in Figure 1 without relying on cross-country differences in the relative importance of technology versus demand shocks. Rather, we focus on differences in labor market adjustment, coupled with variable labor utilization, as the key candidate explanation. In particular, we attribute the procyclicality of labor productivity to variations in effort, which in turn result from a reluctance of firms to adjust the workforce. This idea of labor hoarding dates back to Okun (1963) and Oi (1962). To model labor adjustment adequately, two ingredients are important: labor market rigidities and variable hours per worker.

Employment protection remains restrictive in many countries, especially in the Euro Area. The OECD’s employment protection legislation (EPL) index is defined over a range from 0 (very little protection) to 5 (very stringent protection). Its value for 2019 ranges from 0.09 in the US to 3.6 in the Netherlands. Spain is a special case. While workers on permanent contracts enjoy a high degree of employment protection, temporary contracts with low firing costs are widespread. This dual labor market gives rise to US-style labor market flexibility, reflected in high employment volatility (see Figure 1). There is also large variation in redundancy pay across countries; data from the World Bank’s Doing Business Report 2017 range from zero in the US to 27 weeks of salary in South Korea, and yet higher numbers for non-OECD countries.

High costs of laying off employees in times of low demand discourage labor adjustment along the extensive margin. Already Nickell (1979) found that hours fluctuations were higher and employment fluctuations lower after the 1966 Redundancy Payments Act increased the cost of dismissal in the UK. In a sample of 20 OECD countries over the period 1975-1997, Nunziata (2003) shows that stricter employment protection and looser working time regulations were associated with a lower variability of employment over the cycle. This finding is confirmed in more recent data by Gnocchi et al (2015).

Today, around one half of the adjustment in total hours worked in the Euro Area is through changes in hours per employee rather than changes in employment (Dossche et al, 2019). Short-time work (STW) schemes and working time accounts, used extensively e.g. in Germany, make hours worked more flexible. Lydon et al. (2019) show that the STW take-up rate among firms is positively related to greater firing costs and more stringent employment protection.

Our final crucial model ingredient is variable labor utilization, or effort. Labor effort cannot be observed directly. However, several indirect measures suggest that it is positively correlated with the business cycle: workplace accidents, sick leave, indicators of bad health outcomes are all pro-cyclical. Firms report that they pay more for labor in recessions than is strictly necessary. Evidence from workers’ time use surveys and self-reported effort point in the same direction. According to the prominent ‘shirking’ theory, effort results from the fear of being laid off when caught slacking off at work. Workers exert more effort during downturns when the probability of finding another job is relatively low. Indeed, a couple of papers find evidence of countercyclical effort in a single firm, suggesting that shirking might play a role at the micro level. At the macro level, though, the evidence overwhelmingly supports procyclical effort.

We develop a business cycle model with capital and three labor margins: employment, hours per worker and effort per hour. Importantly, firms face employment adjustment costs, which use up part of their output. Workers are expected to provide a certain amount of effective labor; they choose the combination of hours and effort per hour that minimizes their disutility from working.

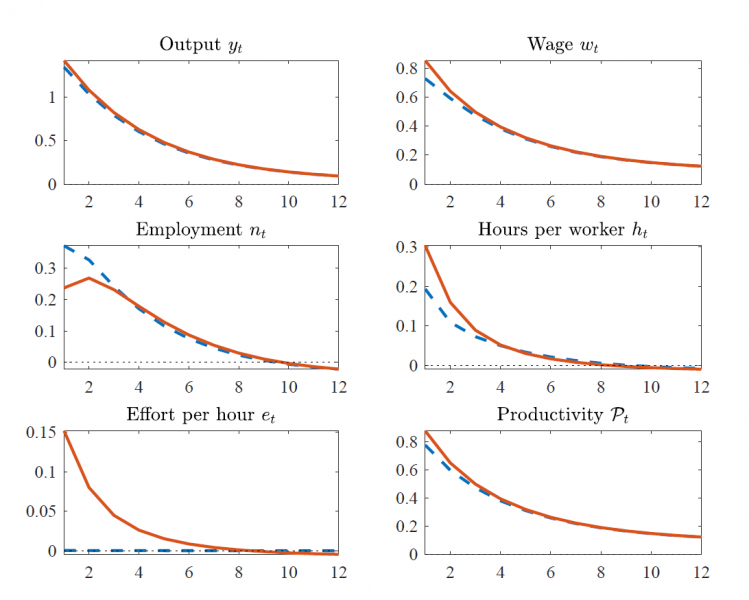

Figure 2: Baseline model responses to one-percent technology shock

Notes: Blue dashed lines show constant-effort model, red solid lines show model with variable labor effort. Impulse responses measured as percentage deviation from steady state. Horizontal axis shows time horizon in quarters.

Consider Figure 2. In the standard model without effort, depicted by the blue dashed lines, employment and hours rise in response to a positive technology shock, while measured labor productivity increases. In the presence of variable labor effort (red solid lines), also effort expands. Hours increase by more, and employment by less, than in the constant-effort model. This allows firms to economize on employment adjustment costs. Labor productivity responds in a procyclical fashion, rising by more in the model with effort.

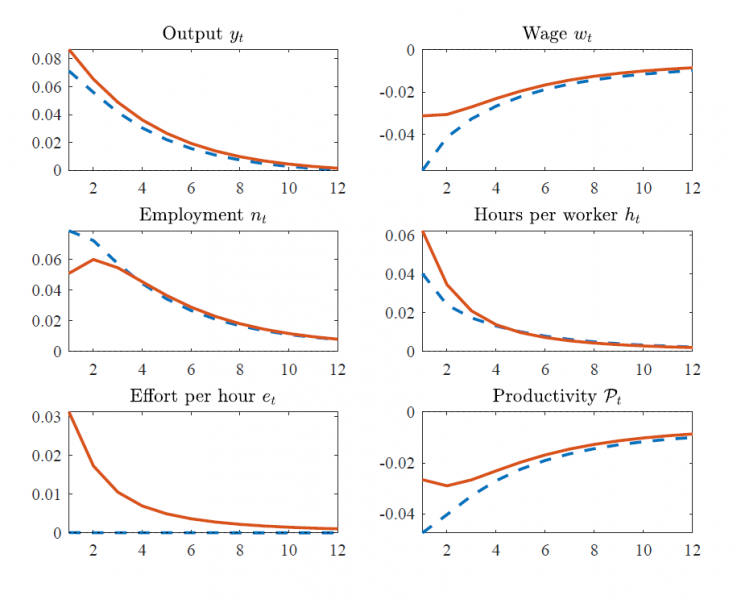

Figure 3: Baseline model responses to one-percent demand shock

Notes: Blue dashed lines show constant-effort model, red solid lines show model with variable labor effort. Impulse responses measured as percentage deviation from steady state. Horizontal axis shows time horizon in quarters.

An expansionary demand shock is depicted in Figure 3. Also here, the presence of variable effort shifts part of the adjustment away from the extensive margin and towards the intensive labor margin. Employment moves by less, while hours and effort adjust by more in response to the shock. Labor productivity is countercyclical conditional on the demand shock. With variable effort, measured productivity drops by less than in the constant-effort model. As a result, the drop in the wage is visibly reduced.

We show that, in a model with labor effort, greater employment adjustment frictions imply more procyclical labor productivity along with more stable employment, consistent with the observed cross-country heterogeneity. The constant-effort model fails to replicate the pattern in the data. As a consequence, labor market deregulation – a reduction in firms’ employment adjustment costs – reduces the cyclicality of labor productivity by more when effort can vary than in the case where effort is constant. Variable effort is thus relevant for evaluating the effect of such a reform. An important lesson from this exercise is that the cyclicality of labor productivity does not in itself reveal the relative importance of technology versus demand shocks as the dominant source of fluctuations.

The labor adjustment process with its associated costs is complex, multi-faceted, and heterogeneous across countries. Further research – ideally focusing on individual countries – is needed to analyze how different types of labor market institutions affect both employment volatility and the cyclicality of labor productivity.

Christiano, L., Eichenbaum, M., and Evans, C. (2005). Nominal rigidities and the dynamic effects of a shock to monetary policy. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1):1-45.

Christiano, L. J., Eichenbaum, M. S., and Trabandt, M. (2015). Understanding the Great Recession. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 7(1):110-67.

Gazzani, A. Dossche, M., and Lewis, V. (2021), Labor Adjustment and Productivity in the OECD, May 2021. CEPR Discussion Paper n° 16202, ECB Working Paper n° 2571, Bundesbank Discussion Paper 22/2021.

Dossche, M., Lewis, V., and Poilly, C. (2019). Employment, hours and the welfare effects of intra-firm bargaining. Journal of Monetary Economics, 104:67-84.

Gnocchi, S., Lagerborg, A., and Pappa, E. (2015). Do labor market institutions matter for business cycles? Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 51:299-317.

Hodrick, R. J. and Prescott, E. C. (1997). Postwar U.S. business cycles: an empirical investigation. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 29(1):1-16.

Lewis, V., Villa, S., and Wolters, M. H. (2019). Labor productivity, effort and the euro area business cycle. Discussion Papers 44/2019, Deutsche Bundesbank.

Lydon, R., Mathä, T. Y., and Millard, S. (2019). Short-time work in the Great Recession: Firm-level evidence from 20 EU countries. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 8(1):2.

Nickell, S. (1979). Unemployment and the structure of labor costs. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 11:187-222.

Nunziata, L. (2003). Labour market institutions and the cyclical dynamics of employment. Labour Economics, 10(1):31-53.

Ohanian, L. E. and Raffo, A. (2012). Aggregate hours worked in OECD countries: New measurement and implications for business cycles. Journal of Monetary Economics, 59(1):40-56.

Oi, W. Y. (1962). Labor as a quasi-fixed factor. Journal of Political Economy, 70:538-538.

Okun, A. M. (1963). Potential GNP: Its measurement and significance. Cowles foundation paper. Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics at Yale University.