This policy brief draws on ECB Working Paper Nr. 3005 “Why do we need to strengthen climate adaptations? Scenarios and financial lines of defence”, see also “Euro foreign exchange reference rates”. The authors wish to thank Hans-Martin Füssel, Marguerite O’Connell, Eric Ruscher, Christian Buelens, Irene Heemskerk, Quentin Dupriez, Ariana Gilbert-Mongelli, and participants to a presentation at DG Ecfin and DG Clima in Brussels for their comments. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB.

Abstract

In previous notes, we argue that geophysical processes are likely to be accompanied by further climate warming and rising extreme climate events with growing damages and losses. The case for climate adaptation is strong and potential benefits are well established. Yet current adaptation financing is fragmented and inadequate. We also argue that climate adaptation in Europe is held back by three connected limitations: a lack of a unified understanding of what it encompasses, “legal adaptation” still being loosely defined and insufficiently prescriptive, and a growing financing gap stemming from a lack of clear guidance for financial markets. This note discusses two crucial aspects. First, what we know about the possible adaptation financing needs and gaps in Europe. Second, while mitigation and adaptation are stepped up, there is an urgent need to absorb uninsured rising climate damages. Innovative financial instruments, such as catastrophe and climate bonds, could support challenged insurance coverages.

Estimating prospective adaptation financing needs. Data on adaptation financing needs is more fragmented and less systematic than data on mitigation financing needs. According to a meta study by the IMF, global adaptation needs in 2030 are estimated to reach approximately 0.25% of world GDP per year, but with great uncertainties and disparities across countries.1 The estimated global total is the equivalent of US$260 billion per year. Given that the EU and the UK represent a bit less than 20% of global GDP, a tentative ballpark estimation for EU + UK could be circa € 50 Billion annually based on the IMF meta-study. To put these figures into perspective, the UNEP (2023) Adaptation Gap Report estimated that annual costs of adaptation in Developing Countries alone could range from about US$215 billion to US$387 billion annually by 2030 and rise significantly further by 2050.2 According to UNEP these projections represent 10-18 times more than current financing flows. This gap is expected to increase to US$ 315-565 billion by 2050.

How much should the European Union invest in adaptation? One fundamental difficulty lay in the lack of assessments of the effective costs of various forms of adaptation. This impedes raising and allocating adequate financing, ultimately hindering the implementation of effective climate change adaptation across Europe. Although it is not clear how much countries, regions and sectors should invest in adaptation, several complementary approaches are progressing based on recent country studies (World Bank (2024)).3

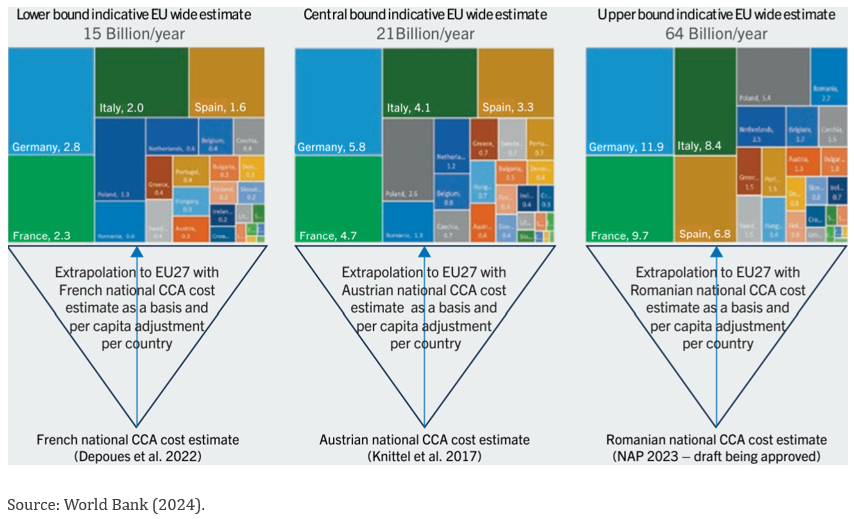

A set of low bounds estimates of adaptation financing needs. Three ranges of EU-wide costs estimate of incremental “no-regret” adaptation measures are extrapolated on a per capita basis from three country specific adaptation studies (Figure 1). The left panel shows a lower-bound estimate of yearly costs of adaptation extrapolated from a French assessment, i.e., €15 Billion EU-wide. The central panel is based on a per capita basis from the Austrian PACINAS study, i.e., €21 Billion EU-wide. Instead, the right panel presents an upper-bound estimate of adaptation costs based on the Romanian National Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan, i.e., €64 Billion EU-wide (which is still preliminary, as the National Adaptation Plan was not yet finalized). These estimates can only be considered as indicative as they do not take account of vulnerabilities or impediments in scaling up from the national level (World Bank (2024)).

Summing up, estimates of adaptation financing need for the EU are still at an early stage but vary widely, ranging between €15 Billion and €64 Billion EU-wide. These estimates can only be considered as indicative because not many European countries have conducted such studies, they do not take account rising vulnerabilities, or impediments in scaling up from the national level, and other obstacles. UNEP 2023 warns that adaptation financing gap for developed countries represent 10-18 times more than current financing flows. Thus, the adaptation financing gap is already staggering and is expected to increase. Given the past, the public sector might be faced with the lion share of financial coverage, yet some novel schemes might crowd-in private financing as well.

Figure 1. EU-27 adaptation financing costs to 2030 extrapolated on basis of country studies

Europe will be faced with more frequent and intense extreme weather events, stretching current preparedness and response capacity. The EU governance framework will need to promote structural changes to deal with systemic impacts on all economic sectors (EEA (2024)).4 The EU economic governance framework — that has evolved over many decades — comprises both institutions and procedures the EU has set up to coordinate member states’ economic policies and to achieve its economic objectives. The framework contains an elaborate system of policy coordination and surveillance. It relies on the principles of monitoring, preventing, and correcting economic trends that could weaken individual member states’ economies or cause spillovers to other economies.5 Climate change is impacting all layers of the governance framework.

Governments generally cover a large share of the uninsured costs of climate disasters relief, recovery and reconstruction. This will likely pose a growing challenge for public finances. As discussed in previous sections, unabated climate change is expected to amplify the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events weighing on national budgets. This could have significant implications for national budgets as well as the EU’s budget and financial facilities. Adaptation efforts require substantial additional investments in infrastructures, technology and innovation, and other measures to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change.

To enhance adaptive capacity, the reformed economic governance framework is encouraging proactive “green budgeting.” To improve budgetary planning and redirect public revenue and expenditure to green priorities, the Council Directive on national budgetary frameworks has been updated.6 The new provisions introduced into the Council Directive on national budgetary frameworks requires Member States to report current and past macro fiscal risks from climate change, climate-related contingent liabilities, and fiscal costs of disasters. In their national budgetary strategies, Member States should pay attention to the macro-fiscal risks of climate change and their impact on public finances and limit and manage the risks which can have environmental and distributional impacts. Moreover, under the new Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) Preventive Arm Regulation,7 Member States are required to prepare national medium-term fiscal structural plans. These plans must, inter alia, explain how Member States will address the objectives set out in the European Climate Law through the planned reforms and investments included in their national plans.

In recent decades, the European Union has created new financial facilities to address various worthy policy priorities. Over time these initiatives also address challenges stemming from the impact of unabated climate change. In its long-term budget for 2021 – 2027, the European Union has increased the spending target for climate actions to 30% including funding that supports climate adaptation and resilience building. Financial support for climate adaptation as well as other climate policies is becoming available via, inter alia the Recovery and Resilience Fund, the Just Transition Fund and the European Structural and Investment Funds.

European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIFs). For the financial period 2021 – 2027, there are five ESIFs whose objectives include the promotion of climate change adaptation, risk management and prevention. All ESIFs pursue the EU’s goal of economic, social, and territorial cohesion (Article 3 of the Treaty of the European Union and Article 174 of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union). ESIFs include:

Additional facilities might support recovery after climate disasters and climate adaptation:

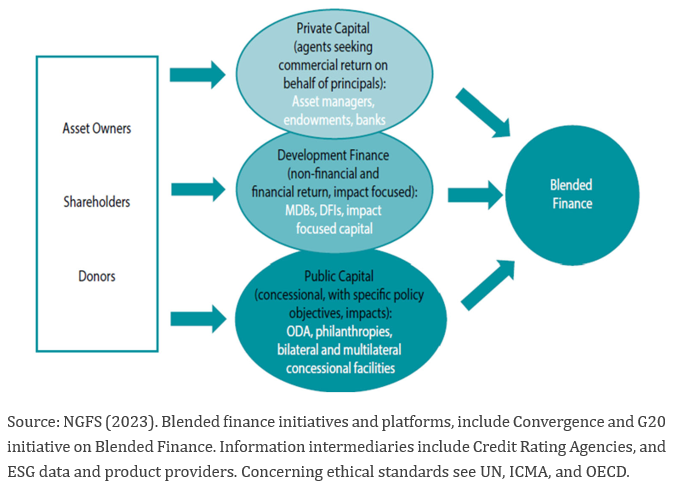

Given the paucity of financing of climate adaptation, are there additional approaches being tested? Yes, by means of a blended finance approach (Figure 2). The NGFS defines blended finance as “… the strategic use of a limited amount of concessional resources to mobilize financing from public and private financial institutions to achieve climate impacts.” (NGFS (2023)).8 Since its early adoption, a growing number of new initiatives have been supporting the mainstreaming and scaling up of blended finance as a tool to attract private financing. According to the OECD, blended finance needs to attract commercial capital towards projects that contribute to sustainable development, while providing financial returns to investors.

Figure 2. Blended Finance Ecosystems

Summing up, the empirical evidence on financing of climate adaptation is patchy and fragmented. Adaptation financing is currently dwarfed by mitigation financing and the public sector is today the principal source of scarce adaptation financing. Thus, seeking ways to attract private investment is important. On the other hand, the EU has over the decades created several financial facilities to address various policy priorities such as cohesion, convergence, solidarity and so on. Over time these initiatives might be aimed at also addressing challenges stemming from the impact of unabated climate change.

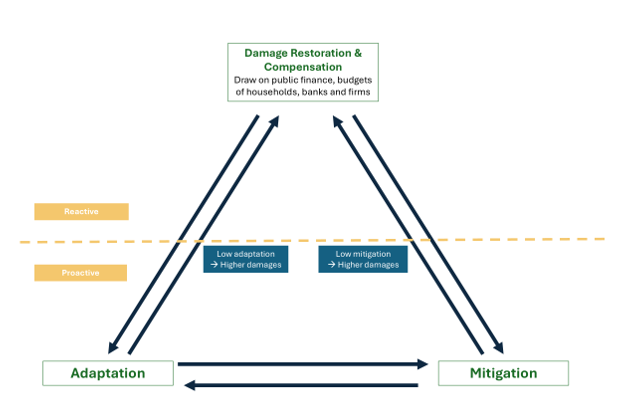

We are mindful of a trilemma between climate mitigation, adaptation strategies, and damage restoration. The trilemma consists of three apexes:

Science warns us that due to climate inertias in the geophysical system, additional warming in the coming decades is already locked in. This also implies that impactful mitigation necessarily unfolds over time with long lags. Adaptation measures therefore are needed to make society more resilient to increasingly severe climate extremes to reduce future damages. A reactive approach relying principally on damage restoration and compensation, for example through public funds and insurance coverage, will become more costly for society, the economy and ecosystem, and fiscally unsustainable, if mitigation efforts are insufficient and adaptation actions are inadequate (see Figure 3).

As mitigation and adaptation are stepped up, it is indispensable to raise various financial market-based “lines of defence.” These are grounded on a sustainable finance framework, insurance coverage, Cat-bonds, Climate Bonds and strengthen other financial safeguards for mitigation and adaptation to be successfully implemented.

Figure 3. Trilemma: climate mitigation, adaptation strategies, and damage restoration

A significant insurance protection gap exists in the EU. Joint work by the ECB and EIOPA show that currently, on average, only 25% of climate-related disaster losses in the European Union are insured and that the insurance gap is expected to widen as the impact of climate change becomes more severe (see EIOPA (2024), ECB-EIOPA (2023) and Rousova et al. (2021)). A particular concern is that some of the climatic zones more exposed to future rising climate hazards (such as the Mediterranean climate zone) are among those with the lowest insurance protection at present.9

A gradual decline in insurance protection, against the background of slow mitigation and adaptation, and locked in continued warming and extreme events, may have a significant impact on the economy. For example, disruptions in the global value chains (GVC) and financial stability (due to the decline in value of insured assets) may ensue. Thus, assessing the state and prospects of the insurance gaps is critical. The international association of insurance supervisors (IAIS) is advocating for a framework to promote public private insurance programs against climate hazards with joint involvement from the IAIS and OECD.

Wider insurance coverage should protect rising shares of households and firms from the damages and losses originating from extreme weather events and climate-related disasters. At one extreme, several governments are already looking to privatize the financing and incentivization of climate adaptation through insurance markets. In a pure market approach to insurance for extreme weather events, individuals become responsible for ensuring they are adequately covered for risks to their own properties, and governments no longer contribute funds to post-disaster recovery (Lucas and Booth (2020)).

Yet, the insurance sector’s contribution to climate adaptation might be neither unbound nor unlimited. Unabated climate change might see an increase in the frequency and/or the intensity of extreme weather events (hazards) which over time might potentially limit the future availability or affordable insurance (OECD (2023)). Insurances firms could bear losses which then might have knock on effects on reinsurances (thus the debate on cat-bonds below).

Adverse incentives? Might insurance coverage of climate related risks provide a false sense of safety and discourage adaptive behaviours? Insurance premiums signal the level of climate risk faced by households, firms, and governments. This should incentivize investments in adaptive actions for risk-proofing, such as retrofitting, drainage work, and fireproofing, to reduce premiums. Where risk is considered too high by insurance markets, housing is devalued or firms value is dented, in theory leading to a retreat from risky areas and or activities. Yet there is also evidence of moral hazard behaviour as well as insufficient risk-proofing and adaptive behaviour.10

Insurance coverage should play an increasingly important role in climate adaptation, while properties and activities might become increasingly uninsurable. The challenges of moral hazards and poor micro adaptive behaviors by households and firms should be acknowledged and addressed. Policyholder risk reduction can be both encouraged and supported. The IMF and OECD have identified approaches that policymakers, regulators and supervisors could consider supporting such as a greater contribution of the insurance sector to climate adaptation (Ando et al. (2022) and OECD (2023)). Possible areas for further work concern re-insurance, supporting a market for catastrophe bonds, and interactions between private and public insurance schemes. Eventually it might be useful to conceptualize the medium- and long- term interactions between adaptation and mitigation.

Catastrophe bonds (cat bonds) are securities linked to natural disaster risks. Their purpose is to transfer the burden of climate related risks from an issuer (generally an insurance company) to investors (generally bond markets), i.e., wholesale investors, not retail. When professional investors purchase cat bonds, they take on the risk of the occurrence of a predefined natural hazard/disaster in return for payments. If the adverse event occurs, investors will lose part, or all, of the capital invested, and the issuer will use the proceeds to cover the damage. Cat bonds were created in the mid-1990s, after Hurricane Harvey in 1992 brought 11 insurance companies into bankruptcy. A detailed description is in Polacek (2018)).

The cat bond market is still relatively undeveloped, especially outside the US. There might be an ESG angle to this asset class. “Over 60% of Schroders Capital ILS assets are classified as Article 8 under the EU’s SFDR. In addition, there are some cat bonds which use ESG-friendly collateral (such as IBRD bonds) thus further increasing the ESG credentials. Cat bonds are also increasingly used with a development angle such as the Chile earthquake bond.” European project Medewsa ties into these mechanisms. The idea of the Medewsa project that started in July 2024 is to explore innovative risk transfer solutions to reduce the climate insurance gap.

A European climate bond and a Global Climate Fund. Monasterolo et al. (2024) propose issuance of a European climate bond. To close part of the EU’s climate investment gap, they propose the joint issuance of European climate bonds by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). Climate bonds would be funded by the sale of GHG emission allowances, traded on the EU Emissions Trading System, extended to cover all sectors (ETS2). Access to the resulting funds would be conditional on Member State’s green performance with respect to the implementation of climate projects. The climate bonds would meet the demand for a safe, liquid, and green asset, while increasing the speed and efficiency of EU climate investments, resilience to sovereign crises, and the greening of investors’ portfolios and monetary policy. Hochrainer-Stigler et al. (2014) instead propose a Global Climate Fund “…covering different risk layers to be in the lower billions of dollars annually, compared to estimates of global climate adaptation which reach to more than USD 100 billion annually.” 11

Summing up, as mitigation and adaptation policies are stepped up, it is indispensable to raise various financial market-based “lines of defence”. A foundation is in place with the EU’s SFF and the taxonomy regulation, the EuGB, the CSRD, the SFDR and the ESG ratings. However, there are concerns about uneven and possibly declining insurance coverages. Insurance coverage is both limited at present and is not a final solution to unabated climate change, escalating climate hazards and rising damages. New financial instruments are being considered such as Cat-bonds, Climate Bonds, and a global climate fund. These would strengthen other financial safeguards as mitigation and adaptation efforts unfold.

We are mindful of a trilemma between mitigation, adaptation efforts and damage restoration. A reactive approach relying principally on damage restoration will become increasingly costlier if mitigation efforts are insufficient and adaptation actions are inadequate. Therefore, it is imperative to adequately invest in both mitigation and adaptation strategies simultaneously in order to reduce damage restoration expenditures.

Heterogeneity and inequality effects of unabated climate change and rising extreme climate events. Adaptation needs can be highly specific to regions and sectors. Local climate data and tailored adaptation strategies are essential (e.g., Florida versus Montana, or Puglia versus Tyrol). Additionally, there are also spillover effects where actions in one area can impact other. The wide heterogeneity and dispersion of climate impacts necessitate a strong role for risk-sharing and cross-regional and sectoral insurance, especially during the implementation of mitigation and adaptation policies which have lags. Lack of local adaptation can generate increasingly important economic and financial spillovers of various kinds, e.g., by interrupting trade and global value chains.

Climate adaptation is among the most complex challenges in modern economics, finance, and political economy. There are several reasons to be concerned about its urgency. We listed just a few. Yet we want to end on a positive note. We now have better granular climate data, there is awareness that adaptation choices must be dynamic and reactive, and there is an increasing pool of case studies about its benefits from which to learn.

The study addresses risks from changes both in average conditions and in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather, by improving resilience to droughts in agriculture, changing where and how crops are grown, managing water resources, addressing sea-level rise, and rendering infrastructures more resilient to extreme weather (see Bellon et al (2022 a and b) and Aligishiev et al (2022)).

UNEP (2023) “Adaptation Gap Report”, see: https://www.unep.org/resources/adaptation-gap-report-2023

World Bank (2024) “Climate Adaptation Costing in a Changing World”, a Report funded by the European Union, see: https://civil-protection-knowledge-network.europa.eu/system/files/2024-05/EDPP2_C2%20CCA%20Cost%20report.pdf

EEA (2024) “European Climate Risk Assessment 2024”, Report 1.2024, see: https://horizoneuropencpportal.eu/sites/default/files/2024-06/eea-european-climate-risk-assessment-2024.pdf

See European Council: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/economic-governance-framework

Council Directive 2011/85/EU of 8 November 2011 on requirements for budgetary frameworks of the Member States, OJ L 306, 23/11/2011, p. 41.

Regulation (EU) 2024/1263 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2024 on the effective coordination of economic policies and on multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97, OJ L, 2024/1263, 30.4.2024.

NGFS (2023) “Scaling Up Blended Finance for Climate Mitigation and Adaptation in Emerging Market and Developing Economies (EMDEs)”, December 2023 see: https://www.ngfs.net/en/press-release/ngfs-publishes-document-scaling-blended-finance-emdes

For a dashboard on insurance protection gaps for natural catastrophes in the EU see: https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/tools-and-data/dashboard-insurance-protection-gap-natural-catastrophes_en. For the EIOPA’s Final Single Programming Document 2024-2026 see here.

Financial literacy has an important role to play. Evidence shows a mismatch between social understandings of responsibility for facing climate risks, and the market-based home insurance products offered by private insurance markets. Moreover, market-based models of insurance for extreme weather events erode the solidaristic and collective practices that support adaptive behaviour (Lucas and Booth (2020)).

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959378014000259