This SUERF Policy Brief summarizes Mojon et al. (2025). The views expressed in this study reflect those of authors and are not necessarily those of the Bank for International Settlements.

Abstract

We introduce a new Monetary Policy Conditions Index (MCI) that integrates conventional and unconventional monetary policy tools into a unified measure. The MCI, defined as a weighted average of short-term interest rate and central bank balance sheet size, improves on the shadow rate by capturing balance sheet policy effects even away from the effective lower bound. The MCI suggests that large balance sheet policies have exerted a significant accommodative influence on monetary policy conditions, while also providing new insights into the effectiveness and unintended consequences of unconventional policies. The framework is flexible and can accommodate numerous extensions, including a structurally larger central bank balance sheet under ample reserve system.

The toolkit of central banks has evolved significantly over the past two decades. Traditionally, the short-term interest rate was the primary instrument of monetary policy. The Great Financial Crisis (GFC) brought new challenges to this framework, prompting many central banks to lower policy rates to their effective lower bounds (ELBs) and adopt a range of unconventional measures, such as forward guidance, liquidity provision, and large-scale asset purchases. Subsequent periods marked further shifts in central banking practices, as policy rates rose but central bank balance sheets in many jurisdictions remained elevated. Consequently, both short-term rates and central bank balance sheets have concurrently emerged as active policy tools.

This evolving policy framework presents challenges for empirical research and policymaking alike, as both rely on consistent time-series of monetary policy settings. Concepts such as the shadow rate (e.g., Wu and Xia, 2016) helped address this, but have become less useful in the most recent regime when both short-term rates and central bank balance sheets are active.1 A comprehensive indicator that integrates the implications of both conventional and unconventional policy tools consistently over time remains notably absent.

To address this gap, we introduce a new aggregate Monetary Policy Conditions Index (MCI). The MCI combines conventional and unconventional monetary policy measures to provide a consistent summary of the overall stance of monetary policy across different regimes. It captures the influence of monetary policy on the economy regardless of whether conventional or unconventional tools – or a combination of both – are in use. By design, the MCI remains applicable both at the ELB and when policy rates are above the ELB, ensuring its relevance across different monetary policy regimes.

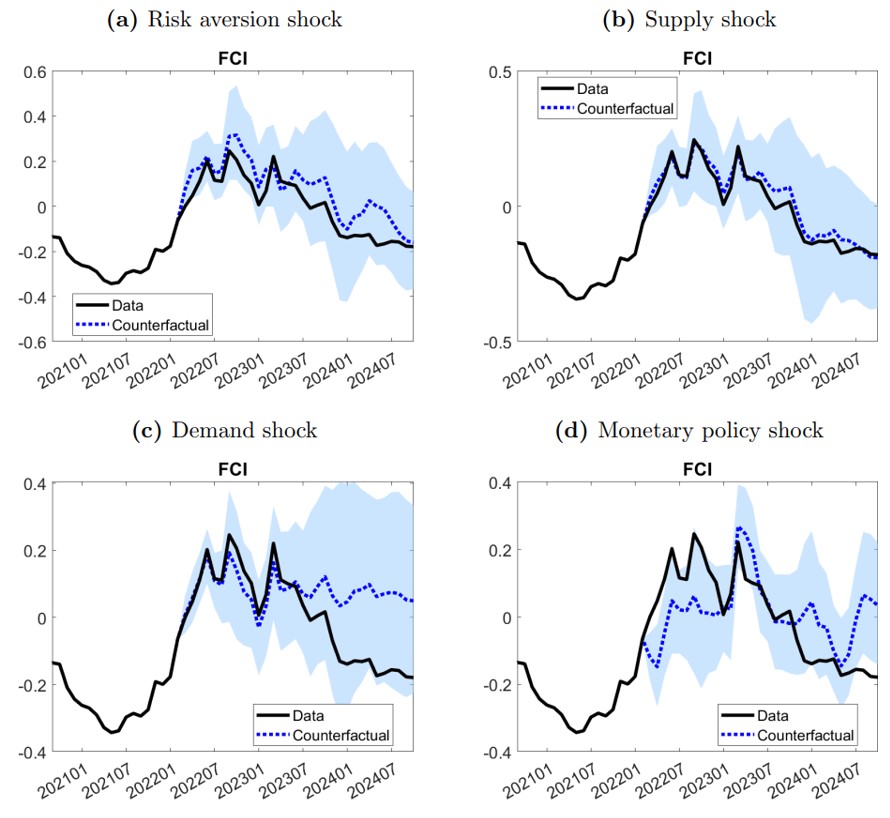

We specify the MCI as a weighted average of the two policy instruments: the short-term interest rate (m1t) and the central bank balance sheet size scaled by nominal GDP (m2t):

![]()

with a positive fraction b to be estimated. Higher MCI means tighter monetary policy (note the negative sign in front of m2t).

The MCI can be expressed in units equivalent to short-term rates, to aid interpretation. In particular, MCI can be re-normalised as:

where m2,2007 is the pre-GFC central bank balance sheet size. This re-normalised MCI coincides with the short-term interest rate over the pre-GFC period, when the central bank balance sheet size was constant as a share of GDP. This allows a direct comparison of monetary policy settings consistently over time, and in the familiar unit of short-term interest rate.

To estimate b and the MCI, we construct a monthly VAR system comprising the MCI, the Chicago Fed Financial Conditions Index, the CBO output gap, and CPI inflation. Estimating b within the VAR system allows the use of standard tools such as impulse response functions and historical decomposition to study the dynamic interactions between the MCI and macro-financial variables. We employ a Bayesian estimation routine that iteratively samples b alongside other parameters, to jointly uncover MCI and estimate the model. This approach also allows us to incorporate previous findings such as Crawley et al. (2022) and Wei (2022) on the relative impact of unconventional monetary policies by specifying a prior distribution for b.

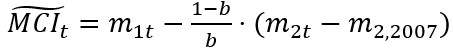

Figure 1 presents the (normalised) MCI and its distribution, alongside the two-year yield and the Wu-Xia (2016) shadow rate. A key observation is that the MCI closely tracks the shadow rate before and during the ELB period, providing an external validation to the MCI estimates. However, in the post-ELB period, a notable divergence emerges between the MCI and both the two-year yield and the shadow rate. As the central bank raised the policy rate above the ELB in 2016, the two-year yield rose significantly above zero, and the shadow rate, by definition, converged to it. While the MCI also increased, its level remained well below that at the start of the ELB period, reflecting the persistent impact of the enlarged central bank balance sheet.

Figure 1. Monetary policy conditions index

Note: MCI is based on the median posterior estimate of b, with grey shaded area reflecting the one standard deviation band of b posterior estimate. Shadow rate is based on Wu and Xia (2016).

Armed with the estimated MCI and VAR, we identify key structural shocks that have shaped the macroeconomy and financial conditions – including supply, demand, risk aversion, and monetary policy shocks – through sign restrictions. The analysis sheds light on several key questions.

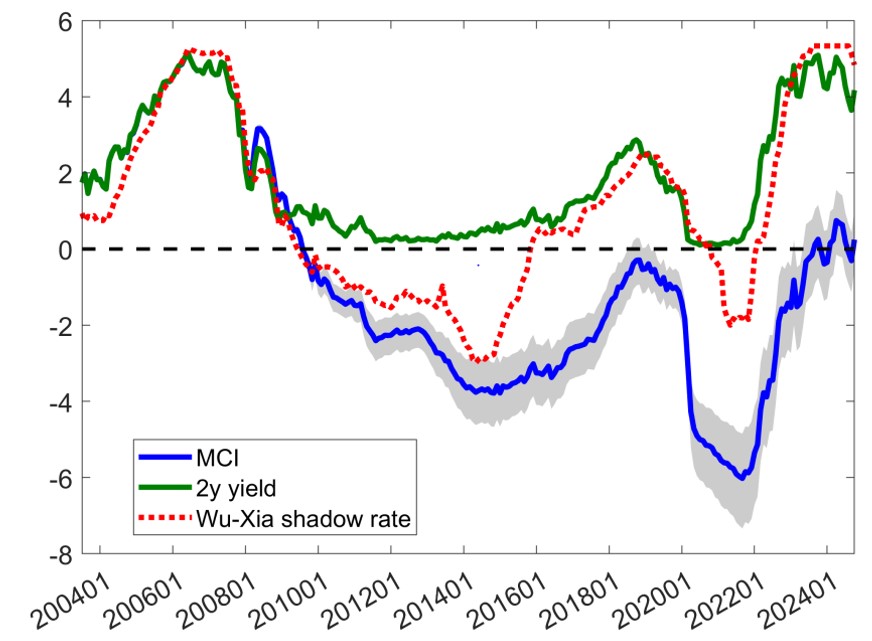

Did monetary policy contribute to the post-pandemic surge in inflation? To explore this question, we consider a counterfactual scenario where monetary policy had adhered to its usual reaction function and did not engage in extraordinary accommodation to mitigate the downside risks during the pandemic. The counterfactual simulation, illustrated in Figure 2, indeed points to the MCI being notably more accommodative than implied by the average policy reaction, even as the short-term rate was constrained by the ELB. As intended, such extraordinary policy accommodation helped ease financial conditions and support higher output levels than would otherwise have been possible. At the same time, the policy response also contributed to higher inflation, which at its peak was one percentage point above what it would have been otherwise. This exercise highlights both the benefits and the unintended consequences of monetary policy actions during the pandemic.

Figure 2. What if there is no forceful pandemic response

Note: The figure shows model simulation, with median counterfactual paths shown in dashed blue lines and data shown in black lines. Counterfactual paths assume zero MCI shocks during the ELB period of March 2020 to February 2022. Shaded areas represent the one standard deviation band.

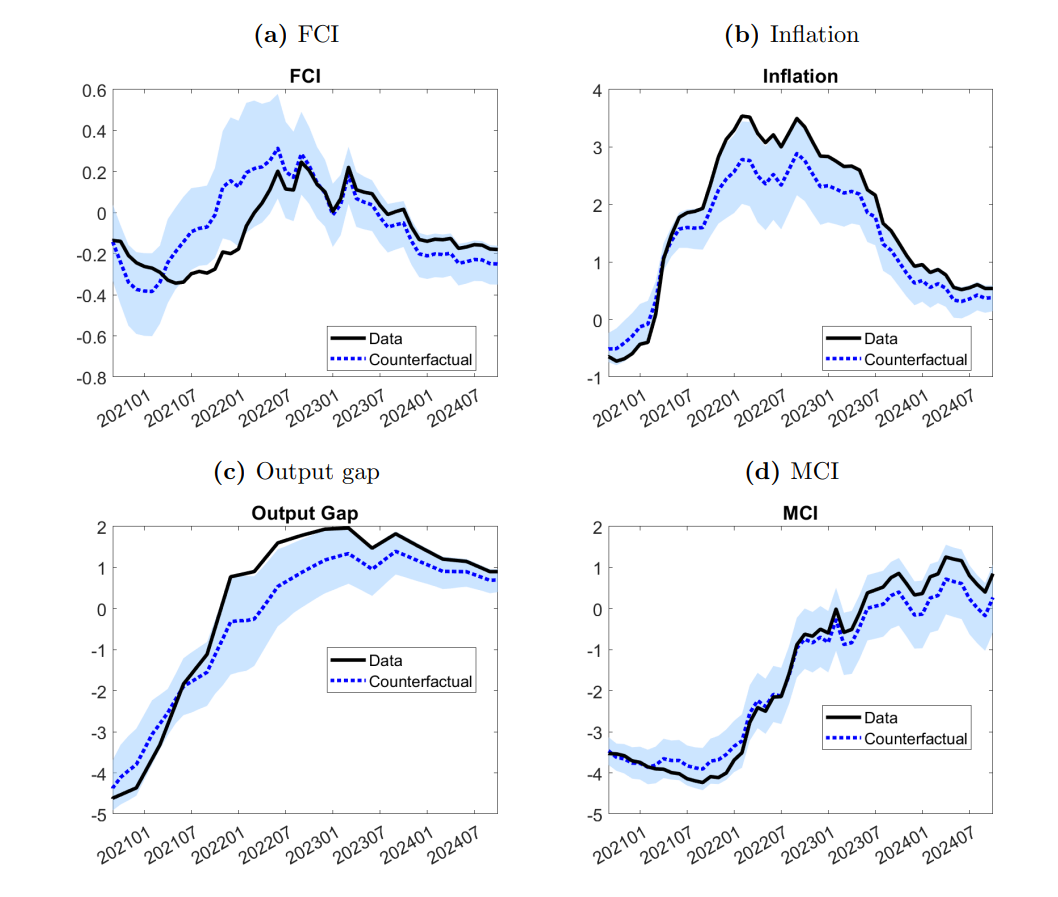

Why have financial conditions remained easy despite sharp monetary policy tightening post-pandemic? To shed light on this seeming disconnect, we quantify the role of each structural shock by shutting it down one at a time to construct four counterfactual scenarios. As shown in Figure 3, demand and monetary policy shocks emerged as the most significant drivers of the recent easing in financial conditions. Softer-than-expected economic activity has contributed to an easing in the FCI by keeping monetary policy looser than otherwise would have been the case –without such demand shocks, FCI would have remained close to its 2022 average. Monetary policy shocks have also exacerbated FCI volatility – absent such policy shocks, FCI would not have tightened as much in 2022 in the first place and would have remained closer to its historical average throughout the period.

Figure 3. What drove easing financial conditions post pandemic

Note: The figure shows model simulation of FCI, with median counterfactual paths shown in dashed blue lines and data shown in black lines. In each panel, the counterfactual path assumes the absence of one structural shock after March 2022. Shaded areas represent the one standard deviation band.

Could the “new normal” central bank balance sheet have grown over time, and what are the policy implications? One argument is that the financial system today may require a higher supply of central bank reserves to meet post-GFC regulations and satisfy liquidity needs amid less active interbank market. Central banks may need to keep their reserves ample and balance sheets large, due to higher demand for their liabilities – the “liability channel”. At the same time, maintaining large balance sheets could keep financial conditions loose through the stock effects of asset purchases – the “asset channel”. Our MCI framework can be readily extended to accommodate both mechanisms, including the potentially nonlinear nature of the liability channel (i.e. the system operates smoothly independent of policy until reserves become scarce). One insight from such analysis is that the balance sheet policy under ample reserve system may never be truly neutral, as satisfying higher demand for reserves requires larger asset holdings which necessarily loosen financial conditions. The MCI framework provides a tool for internalising such effects when formulating monetary policy.

The central bank balance sheet has become a regular instrument of macroeconomic stabilisation policy, raising important questions about how to gauge monetary policy stance when both interest rates and balance sheets are active tools. To address this, we introduce a new Monetary Policy Conditions Index that captures the effects of both conventional and unconventional policy measures. We demonstrate its use through several empirical exercises, highlighting the framework’s flexibility and wide applicability in addressing key policy questions.

Crawley, E., E. Gagnon, J. Hebden, and J. Trevino (2022): “Substitutability between balance sheet reductions and policy rate hikes: some illustrations and a discussion,” FEDS Notes.

Wei, B. (2022): “Quantifying ‘Quantitative Tightening’(QT): How many rate hikes is QT equivalent to?” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Papers, No 2022-8.

Wu, J. C. and F. D. Xia (2016): “Measuring the macroeconomic impact of monetary policy at the zero lower bound,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 48, 253–291.

Mojon, B., P. Rungcharoenkitkul and F. D. Xia (2022): “Integrating balance sheet policy into monetary policy conditions”, BIS Working Papers, No 1281.

By definition, the shadow rate converges to the policy rate above the ELB and consequently does not take into account the effects of persistently large central bank balance sheets.