This policy note is based on the “Strengthening Financial Stability through Insurance-based Credit Risk Transfer” (Bell et al. (2025)) paper available on PCS’s website (https://pcsmarket.org/) and on a Eurofi policy note “Expand STS credit protection to the non-life insurance sector“ available on Eurofi’s website (www.eurofi.net), updated to take into account the latest legislative developments (“Securitisation Package”) published on 17 June 2025 by the European Commission. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to Prime Collateralised Securities (PCS), Arch Insurance (EU) dac, Great Lakes Insurance SE (GLISE), the International Association of Credit Portfolio Managers (IACPM) or VYGE Consulting.

Abstract

Non-life (re)insurers have long offered credit risk insurance on individual loans and, since 2018, on loan portfolios via Significant Risk Transfer (SRT) securitisation. However, in the EU, their capacity in Simple, Transparent and Standardised (STS) SRT securitisations remains untapped because since 2021, the EU synthetic STS rules exclude (re)insurers as unfunded protection providers on these transactions. This SUERF Policy Note contrasts (re)insurers’ risk-bearing model with funded investors, outlines the US Federal Housing Finance Agency Credit Risk Transfer (CRT) framework benefiting since 2013 from the inclusion of both capital market investors and (re)insurers, assesses the EU STS collateralisation criterion and concludes that removing this barrier — with safeguards as proposed by the European Commission, if worded appropriately — would actually strengthen financial stability, market efficiency, and support the EU’s ambitious competitiveness agenda.

As per Commissioner Albuquerque (see EP (2024)), securitisation is a relevant tool separate from past misuse; one must leverage its benefits while preventing and addressing its risks.

Securitisation deserves better than its current reputation in the European Union (EU). It was not the cause of the financial crisis, but rather a conduit for the US subprime mortgage origination disaster to spread globally. In contrast, Europe maintained responsible lending standards, stayed well-supervised, and did not experience massive losses in securitisations. Recognising this distinction is crucial for developing balanced policies promoting financial stability and EU economic growth.

To prevent a repeat crisis, international standard setters developed drastic measures to regulate securitisations. While many aspects were reasonable and codified existing EU best practices, an element of ‘overshoot’ has limited the efficiency of the ‘traditional’1 securitisation market. In the EU, a gold-plated version of international standards was implemented, and EU traditional securitisation issuance plunged, even after introducing the Simple, Transparent and Standardised (STS) standard, as its extremely prescriptive requirements were not compensated with a commensurate recognition of its high quality.

Securitisation is a technique that can provide funding to loan originators, issuing senior tranches in traditional format, and/or provide financing via credit risk transfer and commensurate capital relief for banks as issuers. Significant Risk Transfer (SRT) securitisation, executed principally in a ‘synthetic’2 format, enables banks to free-up capital by transferring the “significant” part of the underlying credit portfolio risk to non-bank financial entities, referred to as ‘credit protection providers’, thus enabling a key economic optimisation tool: capital velocity (see SUERF Policy Brief No 976 (2024)). When the STS standard was extended to ‘synthetic’ or ‘on-balance sheet’ (OBS) transactions3, with preferential capital treatment, this segment of the market started to recover, although it excluded credit insurance due to a mandatory collateral requirement4.

The credit protection provider universe is split between private and public sector institutions. Public ones, such as multilaterals (MDBs) like the European Investment Fund (EIF), play a major role in the EU synthetic securitisation market, and have been exempt from any collateral requirement in the synthetic STS framework.

Within private sector SRT, two categories arise from differing commercial considerations, risk appetites, and business models: 1) funded or collateralised credit protection (“Investor SRT”), provided almost entirely by credit or pension funds purchasing bonds or notes, or entering into a bilateral collateralised guarantee or credit derivative contract; and 2) insurance credit protection (“Insurance SRT”), provided by insurers and reinsurers (the “(re)insurers”) underwriting specific securitisation tranches in the legal form of (unfunded) insurance contracts, generally syndicated. These two categories co-exist because insurance business models and risk appetites differ from those of credit or pension fund investors, yet both play complementary roles, boosting the capacity to support banks’ lending growth.

However, Insurance SRT’s full potential remains unrealised in the EU, given the STS collateral requirement. Increasing the number and diversity of eligible protection providers, especially by adding well-rated, well-capitalised and regulated multiline (re)insurers with specialised credit insurance arms, would strengthen financial stability by allowing better shock absorption, as such players have typically a long-term view, like MDBs and pension funds, and are less sensitive to short term market movements. Expanding the role of credit (re)insurers beyond the non-STS securitisation market should be one of the goals of the ongoing EU securitisation reform package.

Transferring credit risk from the highly regulated and supervised banking sector to the equally regulated, supervised, well-capitalised and diversified non-life insurance sector enhances financial stability by reducing systemic risk:

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) framework for securitisation is less prescriptive than its EU implementation. The BCBS Simple, Transparent and Comparable (STC) framework is lighter than the EU’s STS framework, and the concept of SRT is more principle-based. In contrast, the EU has an extremely detailed set of rules on risk transfer, implemented through the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), the Securitisation Regulation (SECR), the European Banking Authority (EBA) guidelines and the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) defined disclosures, and by banking supervisors, especially the European Central Bank (ECB). The EU is also the only jurisdiction which implemented STS rules specific to synthetic securitisation. Given the stricter EU framework, and more than 25 years market experience, it is time to recognise the high quality, resilience and low loss experience of EU securitisations and open the STS market to the credit insurance sector.

On 17 June, 2025, the European Commission’s (EC) “Securitisation Package” (EC (2025b)) proposed allowing (re)insurers to be eligible providers of unfunded protection for synthetic STS without providing collateral.6 Considering the feedback received on this targeted change, the EC introduced four safeguards narrowing eligibility to the most sophisticated, risk-aware and resilient (re)insurers. However, the wording of the proposed safeguards needs further fine-tuning to ensure it aligns with the reform’s objective to safely expand the role of insurers in SRT.

This SUERF Policy Note draws insights from the US for the role insurance companies play in credit risk transfer (CRT), that may inform the debate on how to revitalise the EU securitisation market and advance the EU’s ambitious SIU and competitiveness agenda. It is structured in five sections:

The authors conclude that the EC’s proposal for a targeted change consisting in the removal of this collateralisation criterion in the Securitisation Package for (re)insurers, subject to four (to-be-adapted) safeguards, would enhance financial stability, improve market efficiency, and support economic growth and competitiveness.

The role of insurance companies as investors in traditional securitisations, on the ‘asset side’ of their balance sheet, is well understood. What is less recognised is the large capacity of many non-life (re)insurers on the ‘liability side’ of their balance sheet: underwriting SRT with credit insurance policies is a natural extension to their expertise in their core loan-by-loan credit insurance business or of their CRT business in the US.

(Re)insurers primarily underwrite uncorrelated exposures — natural catastrophes, property, casualty, and life — ensuring stable results across cycles if tail risks are avoided or protected. Since credit defaults seldom correlate with these risks, offering credit protection produces valuable diversification, enhancing overall risk portfolio resilience.

In response to real-economy demands, non-life (re)insurers over time developed credit insurance to protect banks and corporates from credit losses on mortgages, trade and project finance, and SME and corporate loans. For over two decades, they have provided banks with uncollateralised cover on individual loans, without systemic or policyholder concerns, including during market stress. By end 2023, European insurers shared risk with banks on roughly $360 billion of credit facilities,7 thereby broadening the number of loans and investments that become ‘bankable’. Protecting securitised credit portfolios in the EU is nothing more than a natural extension of the loan-by-loan credit insurance business. The same applies to (re)insurers already active in the mortgages CRT programs of US GSEs.

As a matter of principle, the insurance business model is based on accumulating a diversified portfolio of uncorrelated risks — multiline non-life (re)insurers have highly diversified business models, as demonstrated by the fact that credit insurance premia represent a minor part (2.2%)8 of their total gross written premia (GWP) — and are proactively managing portfolio concentration by syndicating the risk to other insurers and capital market investors, and (re)insuring tail risks with reinsurance companies. As (re)insurers’ assets must remain unencumbered to pay claims, the business model and pricing of insurance policies do not contemplate the upfront collateralisation of insurance policies. Nor do they need to because of the benefits of diversification. To clarify, insurance obligations are supported by the strong balance sheets of regulated entities, balance sheets made resilient by the diversified premium received from uncorrelated insurance contracts, and are not, therefore, collateralised. In securitisation regulatory terminology, they are ‘unfunded’. This is why the collateralisation requirement included in the EU 2021 synthetic STS securitisation legislation, originally intended to address the potential counterparty risks resulting from credit derivatives, does not fit the insurance business model and de facto excludes (re)insurers from conducting synthetic securitisation business in STS format (more of which, later).

Investors in collateralised risk transfer differ, consisting mainly of asset managers and specialised credit funds but also pension funds, who are in the business of investing the cash that the asset owners have entrusted them with, and therefore provide funding, in addition to risk mitigation. The business models and risk appetites of (re)insurers and collateralised risk transfer investors are therefore different, though playing complementary roles, and both have the potential to provide important financing capacity to the economy.

In other jurisdictions, to increase the number of non-bank counterparties that are risk takers, the UK has just published on 18th July 2025 a policy change9 allowing (re)insurers to become guarantors for uncollateralised synthetic SRT transactions. Similarly, in the US, the Government Sponsored Entities (GSEs) benefit since 2013 from the combined participation of capital market investors and (re)insurers in their CRT programs.

In the US, the most prolific participants in the credit risk transfer (CRT) market are the GSEs, who buy portfolios of mortgage loans from banks and other originators. In the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) —during which the GSEs had to be put in ‘conservatorship’ after incurring massive losses— the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), the regulator responsible for overseeing the GSEs, established CRT programs to allow them to continue to purchase large amounts of mortgages and provide critical liquidity to the mortgage finance market, while transferring risks away from their government-guaranteed balance-sheet to protect taxpayers.

Overseeing a vast market, FHFA approaches financial stability from a practical rather than theoretical perspective: it sets clear rules and targets, monitors outcomes, and continuously refines its framework. Since 2013, GSE CRT programs have transferred to market participants the risk on over $6.7 trillion of mortgages, with a combined amount of risk absorbed by third-party market participants of over $200 billion.

FHFA assesses all GSE credit risk transfer activities using the same key CRT principles, four of which focus on ‘stability’:10

The first principle — reduce taxpayer risk — was set in 2012 to limit taxpayer exposure to credit guarantees by GSEs, using strategic plans and scorecards to encourage credit risk transfers to the private sector. The 2012 strategic plan introduced “loss-sharing agreements”, and the 2013 scorecard required each GSE to demonstrate multiple CRT structures on single-family loans. A 2014 strategic plan emphasised the desirability of greater use of CRT, while the 2014 and 2015 scorecards set increasingly ambitious transfer targets. Since then, scorecards have mandated ongoing transfers, culminating in the latest requirement that GSEs “transfer a meaningful amount of credit risk to private investors in a commercially reasonable and safe and sound manner, reducing risk to taxpayers.”11

The second principle — broad investor base — ensured from the start of the CRT programs that both funded investors and unfunded (re)insurance companies could enter the market. One of the first deals was an insurance policy with Arch Reinsurance Ltd., which the 2013 Acting FHFA Director praised as unique for involving a diversified non-mortgage insurer and for showcasing another risk-sharing approach, while supporting the 2013 Conservatorship Scorecard and FHFA’s Strategic Plan, reducing Freddie Mac’s market footprint, and ultimately protecting taxpayers.

FHFA’s 2015 discussion of the third principle — stability through economic and housing cycles — acknowledged that the launched CRT programs to transfer credit risk to the private sector were an innovative effort involving the creation of new markets with many unknowns, notably whether investors would stay through a housing downturn and if higher interest rates and attractive fixed-income alternatives could affect the investor base and pricing. Nevertheless, FHFA considered how the CRT market could endure a housing price cycle and outlined elements to ensure a stable, resilient market. The first three elements were:

“a) Develop innovative methods of credit risk transfer that encourage investment throughout the housing market cycle, particularly during adverse market conditions as experienced in 2008;

b) Use multiple types of transactions designed to attract a wide variety of investors;

c) Continue to expand the investor base for securitized products as well as look for additional sources of private capital to participate in credit risk transfer activities;” (FHFA (2015))

FHFA’s focus on stability through economic and housing cycles proved prescient during COVID-driven market turmoil, highlighting the critical role of a diverse investor base and the value of including (re)insurers from day one. When funded investors pulled back from the CRT market amid turbulence in debt and equity markets, having (re)insurers already in the CRT space helped stabilise both prices and continuity of risk taking in that market. The share of residential mortgages covered by (re)insurers after this ‘baptism by fire’ was boosted to reinforce resilience (see Box 1).

The fourth principle — counterparty strength — is relevant only to the unfunded CRT programs. FHFA (2015) explained (emphasis added):

“[…] one advantage of conducting transactions with reinsurers is that they are generally diversified in their risk exposures. This may result in lower counterparty risk because their book of business risk should be less correlated with the [GSE]’s book of business risk and thus may be better able to withstand a home price stress cycle than a monoline mortgage insurer.”

Box 1. Since COVID, there is an increased usage of Insurance CRT by the GSEs in the US

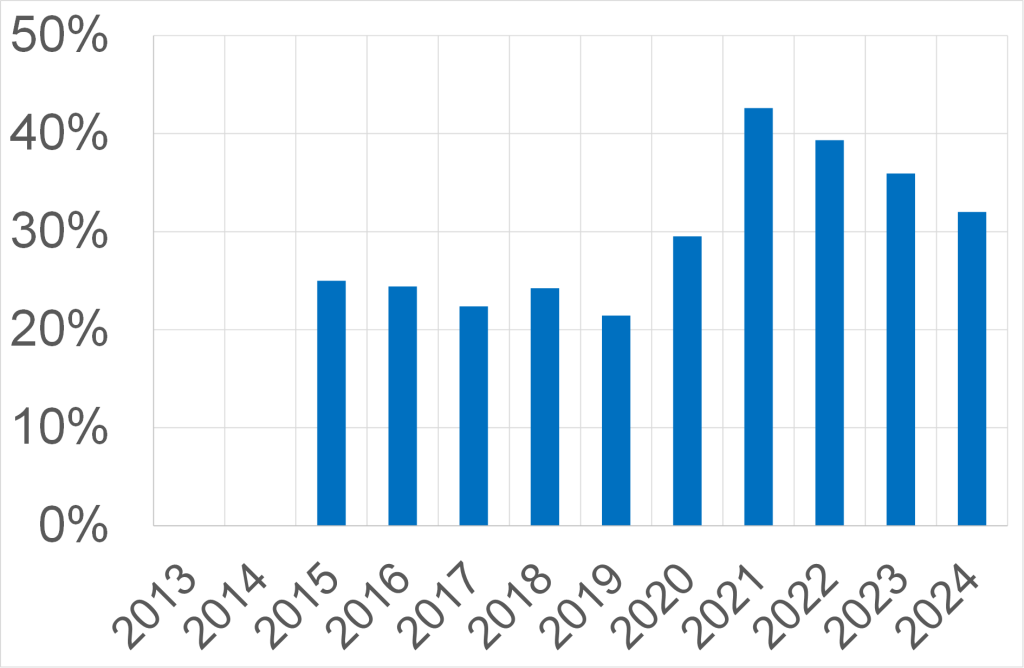

In the US, the CRT programs, initiated in 2012 and launched in 2013 by FHFA, responsible for overseeing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, include both insurance and fully collateralised or ‘funded’ programs for capital markets investors. The diversity of protection providers (funded investors and (re)insurers) is a key strength of the programs. This became apparent during COVID, when the participation of regulated (re)insurers broadly increased as the willingness of funded investors to participate decreased. As a result, the GSEs increased their use of insurance to roughly 40% of their CRT trades from 25% (see Figure 1).

This combination of both capital markets and (re)insurance in the CRT programs had a positive impact on financial stability (stabilisation of prices and continuity of risk taking) across varying economic conditions.

Figure 1. Percentage of Total GSEs’ CRT tranches placed with Insurers

Source: FHFA Scorecards, Annual reports and CRT Progress reports

The robustness of a market increases with the number of participants. Over the last decade, for the GSEs’ CRT programs, the number of (re)insurers has steadily increased and reached more than 60 (compared to slightly more than a dozen in the whole European SRT market). By end 2024, those 60+ (re)insurers protected about $64 bn of risk referencing $1.6 trillion of US residential mortgages owned by the GSEs.12

European policymakers argue the EU needs “massive private investment” to drive its climate and digital agendas, finance defence, and boost productivity and competitiveness. Central to this are EU banks, which intermediate domestic and international savings via debt finance and have been recognised as well-capitalised —Core Equity Tier 1 ratios rose from 6% in 2011 to 16% by end 2023. However, they have struggled with price-to-book ratios below one for over a decade, underscoring their weaker competitiveness compared to global peers (see Ormezzano (2024)). Due to the price-to-book ratios below one, raising capital from new equity issuance is unattractive for banks. Thus, the macroeconomic objective of financing the massive investments needs called for by policymakers is endangered without regulatory reform.

Rather than raising new capital, EU banks must leverage existing capital more efficiently to support growth: it needs to acquire velocity. Securitisation achieving SRT is the most scalable technique that can generate ‘capital velocity’. It redeploys risk capacity for new lending, if capital relief matches the reduction in credit risk. Securitisation reforms need to tackle overly conservative prudential and non-prudential rules that limit issuance, while simultaneously removing barriers on the risk-taking side to ensure that any increased bank offer of risk is met by increased risk sharing capacity from (re)insurers.

Although dating back to the 1990s, the European (EU + UK) synthetic (on-balance-sheet) SRT market has expanded in the last few years. By end 2024, based on IACPM annual bank SRT survey, €374 billion of EU bank loans were protected by €32 billion (8.5%) of SRT junior tranches, with €148 billion of loans securitised in 2024 (Joulia-Paris et al. (2025)). Initially limited to large banks in large Member States, it has started to extend to smaller banks across smaller Member States, aided by the EIF; the EU SRT growth in 2024 comes exclusively from issuance by non-GSIB banks.

Although synthetic SRT has been enabled by regulation and supervisory guidance since 2006, the 2021 amendments to the Securitisation Regulation (SECR) under the Capital Markets Recovery Package (CMRP), known as the ‘COVID Quick Fix’, extended the STS label to synthetic SRT, boosting the market by granting greater capital relief for the senior tranche retained by banks. However, the COVID Quick Fix’s requirement of full collateralisation for protections for counterparties other than zero risk-weighted public sector ones (such as multilaterals) has unintentionally barred (re)insurers from the STS segment, effectively closing the EU’s STS synthetic SRT market to them.

Banks cannot benefit from the STS label when sharing risk with regulated and supervised (re)insurers via their insurance business, even though they value insurers’ financial strength, relationships, expertise, and long-term commitment. (Re)insurers began offering credit protection through SRT transactions in Europe in 2018, when funded and unfunded securitisations enjoyed equal regulatory treatment. However, since 2021 their market has fragmented, confining them to non-STS SRT securitisations in the EU, which are less capital-efficient for banks. By end 2024, SRT tranches insured by European (EU+UK) banks amounted across various asset classes to about €6 billion13 — 10 times below US GSE CRT volumes — revealing a resilient but underutilised risk-bearing capacity in Europe.

Recognising the missed opportunity for the EU, the EC included specific questions14 on the potential role of credit insurers in its October 2024 targeted consultation (EC (2024)). The majority (66%) supported reversing the exclusion (8% opposed, 26% no opinion). Notably, responses from Austria, Italy, Poland and Portugal — whose banks have struggled to qualify for the STS label — backed these changes.

Of the few regulators who provided explanations in the October 2024 consultation on unfunded credit protection, Spain and France were among those that responded.

In their joint reply, Banco de España and Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (CNMV) back only EU insuring companies with a minimum credit rating as unfunded credit protection providers. They argue that allowing non-EU or non-insurer entities — often lacking strict prudential oversight — could pose financial stability risks, as the capital relief achieved by the originating bank would vanish abruptly in case of a default of the protection provider (Row 73 in EC (2025a)).

The joint response from the French authorities (ministère de l’Economie, Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF), Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution (ACPR), Banque de France (BdF)) noted that since 2021 collateralisation requirements have driven insurers out of the synthetic STS market into non-STS transactions, and argued that any reopening of SRT unfunded credit protection under the STS label must be examined according to five parameters — (i) existing unfunded protections in the non-STS market, (ii) the types of actors providing protection, (iii) potential market-behaviour effects, (iv) risk transfers between originators (mostly banks) and protection providers (mostly (re)insurers), and (v) necessary safeguards — and mentioned that such reopening would send a strong signal requiring careful assessment for EU financial-stability implications (Row 27 in EC (2025a)). In a subsequent position paper, ACPR and Banque de France elaborated on those safeguards, emphasising that (re)insurers acting as protection sellers need robust risk-management systems to measure and manage synthetic securitisation risks, that the Solvency II standard formula may not adequately capture those risks, and that proper internal models — or at least rigorous assessments of deviations from the standard formula coupled with additional capital requirements — are essential (BdF (2025)).

Although the EC consultation benefited from technical exchanges with EBA, ESMA, EIOPA, and ECB staff, only the ECB formally responded by the deadline —and did not address unfunded credit protection. Instead, on March 31, 2025, the three European Supervisory Agencies (EBA, ESMA, EIOPA) published a Joint Committee (JC) Report on the Securitisation Regulation, offering insights and recommendations on non-prudential issues considered in the consultation, notably evaluating whether (re)insurers could qualify as STS-eligible unfunded credit protection providers, The report outlines pros and cons15 — highlighting monoline insurers’ risk (where the protection seller’s default risk closely tied to its credit underwriting) — and, while it expressly mentions that it “does not include a recommendation”, it advises that any STS eligibility comes with appropriate safeguards to address increased counterparty default risk, potential systemic risk, and policyholder protection concerns16 (JC of the ESAs (2025)).

On May 5, 2025, as the EC proposal was already nearing its final draft, the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) released “Unveiling the impact of STS on-balance-sheet securitisation on EU financial stability”, underscoring historical monoline insurers’ risk. In its concluding paragraph, it cites the JC Report’s pros-and-cons analysis of allowing (re)insurers as eligible unfunded protection providers but, unlike the JC’s neutral tone, the ESRB warns that the drawbacks — especially a potential contagion channel17 (due to the ‘cliff-edge effect’) from the (re)insurance sector to banks via concentration and counterparty risk — would outweigh any benefits (ESRB (2025)).

To address the rating-related ‘cliff-edge effect’, the EC and the co-legislators updated CRR Article 201(1) on 31st May 2024,18 with the effect that point (g) no longer applies to “regulated financial sector entities”19 within newly added point (fa) in the list of “eligible providers of unfunded credit protection”. No minimum rating requirement applies to “regulated financial sector entities” within point (fa)20, as regards the SRT criteria. These changes flow through from the general credit risk mitigation framework to the securitisation specific credit risk mitigation requirements, under CRR Article 249(3). Since the relevant changes have been in force since 1st January 2025, the ‘cliff-edge effect’, by which banks would lose the benefit of the SRT recognition, is no longer there for EU (re)insurers. While the EC consultation (EC (2024)) did not specify who the unfunded credit protection providers should be, the ESRB report may have had a valid point for entities other than ‘regulated financial sector entities’. The final version of the ESRB report published on 5th May 2025 could helpfully have reflected this fact, that its conclusion is limited in scope to (re)insurers not included in prudential consolidations under Solvency II (or when specified equivalent third country regimes).

On 17th June 2025 the EC published its Securitisation Package to revise the EU securitisation framework. One key issue relevant to this SUERF Policy Note, addressed in the package relates to the competitiveness impact of the STS requirement that credit protection be funded in on-balance-sheet synthetic securitisations. This requirement restricts (re)insurers participation, hindering STS market development and originators’ ability to transfer credit risk outside the banking system (EC (2025b)).

The EC cited its 2024 consultation and the 2025 JC Report as review inputs; its proposal allows unfunded credit protection providers to participate in STS synthetic securitisations, subject to safeguards on diversification, solvency, risk measurement and minimum size.

1. Following Spanish authorities’ input during the EC consultation, STS credit protection providers must be insurance or reinsurance undertakings which comply with the Solvency Capital Requirement (SCR) and Minimum Capital Requirement (MCR) of the Solvency II Directive21, and have been assigned a rating of CQS 3 or better. This is the solvency safeguard.

a. Here, the scope of eligible insurance regulations should be extended to regulations which are deemed fully equivalent, like Bermuda and Switzerland.22

b. With the current wording, following a downgrade of an initially eligible (re)insurer to a rating below CQS 3, a bank would need to increase marginally its capital requirement by moving from an STS SRT situation to a non-STS SRT one.23 This risk could be mitigated by the (re)insurer itself by providing a counter-guaranteed from another STS eligible (re)insurer. This fits with the (re)insurers’ business model which is to share risk with other (re)insurers, and widening the pool of eligible counterparties increases the likelihood of obtaining these counter-guarantees. In fact, the mechanism already exists in the current rules for public sector entities (SECR Article 26e(8)(b)), but the Securitisation Package, however, overlooked updating it by cross-referencing the new (re)insurer category24. Correcting that omission preserves counter-guarantees25 as an effective market-based stability mechanism, and should alleviate further the ESRB’s concern on the loss of STS status.

c. Another way to mitigate the loss of STS status is to reinforce the current solvency safeguard. All current non-STS transactions with (re)insurers have been done under a minimum CQS 2 rating at “the time of first recognition” of the credit protection. This could be maintained today without impacting the market, and removing the language that implies that this rating needs to be maintained during the life of the transaction would further remove the ‘cliff-edge effect’ mentioned by the ESRB, thus alleviating further their concern about downgrades.

2. Following the JC and ESRB reports’ critique of monoline insurers’ risk, only multiline (re)insurers — those conducting business in at least two non-life insurance classes26 — are eligible, fulfilling the diversification safeguard.

3. In line with French authorities’ feedback during the EC consultation, the EC included a mandatory internal model27 requirement as the risk measurement safeguard, but its 17th June proposal omitted the crucial provision calling for an assessment of deviations between modelled risks and the Solvency II standard formula — a gap that poses significant challenges for most (re)insurers currently active in the non-STS market that are using the standard formula. Under Solvency II, the standard formula and internal models are deemed equally reliable for capital assessment because each approach meets rigorous prudential criteria. Nevertheless, standard formula users must justify its appropriateness through their Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA), demonstrating alignment with their risk profile. Supervisory authorities then review the ORSA and may, where warranted, impose capital add-ons beyond the standard formula requirement. To mitigate concentration risk — given that most European (re)insurers, including many large, well-diversified firms, employ the standard formula — the proposal should allow these (re)insurers to provide guarantees for STS securitisations, provided they meet any additional conditions imposed by their supervisors for writing such guarantees.

4. The safeguard on minimum size imposes a €20 billion total asset28 minimum for insurance undertakings, though the authors of this SUERF Policy Note could not trace any specific stakeholder response to this criterion in the written EC consultation. While the spirit of the proposal is clear in seeking large robust insurers29 with the operational scale to build a diversified portfolio of insured risks, its current wording in the Securitisation Package needs further clarification. Without it, very few underwriting entities active in the market would qualify. Many large, well-diversified European (re)insurers operate with a parent group which owns multiple (re)insurance subsidiaries that hold licences to underwrite sectorally and geographically diversified risk portfolios. Licensing considerations per product and jurisdiction explain the rationale for this approach, which enables a (re)insurer group to underwrite a diversified portfolio of non-life risks. Reflecting this feature of the (re)insurance sector, a size metric based on assets should be assessed either at the subsidiary level or on a consolidated parent basis, provided the subsidiary is wholly owned and the parent undertaking is subject to Solvency II or a fully equivalent regulatory regime. Lastly, to avoid volatile metrics based on fluctuating asset values, the proposal could consider adopting instead a gross written premium (GPW) test — an accounting and regulatory measure familiar to (re)insurers — as a more stable proxy for defining size.

Other minor fixes to the Securitisation Package published by the EC should be implemented by co-legislators to allow (re)insurers to provide unfunded credit protection to STS ‘resilient’30 transactions. By ensuring a broad participation of (re)insurers, and nurturing the conditions for new entrants, concentration risk will be further reduced. Notwithstanding that the concentration risk is by essence limited by banks themselves who have sophisticated limit systems and are effectively supervised. Finally, concerns that (re)insurers may have a competitive advantage over funded investors does not seem borne out by the evidence, as can been seen by the small market share of (re)insurers in the non-STS market.

Multiline non-life (re)insurance companies are sophisticated risk managers with the constant aim of optimising balance sheet diversification and protection of tail risks by re-insurance. Hence, the transfer of some credit risk from the banking sector to the (re)insurance sector would have a clear positive effect on both financial stability and competitiveness because 1) systemic risk reduces in the banking sector; 2) systemic risk reduces in the insurance sector because diversification increases financial stability among (re)insurers; and 3) the banks’ capacity to invest in the real economy increases growth which in itself is a factor of resilience. But the current EU rule, imposing collateralisation of unfunded protection only for STS SRT, is neither consistent with the overall insurance business model, nor commensurate with the actual risks.

Opening eligibility to STS securitisation and ‘resilient positions’, subject to workable safeguards, to insurers’ unfunded credit protection will increase and diversify demand in the market, reduce the average cost of credit protection for banks, strengthen their protection stability by combining a broader base of diversified counterparties, foster competition and lead to larger securitisation volumes.

BdF (2025). “All hands on the green deck: the pressing necessity of a multi-faceted review to revitalise the European securitisation market”, Report, Banque de France – Pôle Stabilité Financière – Autorité de contrôle prudentiel et de resolution, February.

Bell, I., Bennett, M., Duponcheele, G., Joulia-Paris, T., and Ormezzano, V. (2025). “Strengthening Financial Stability through Insurance-based Credit Risk Transfer”, Report, May. (Available on PCS and IACPM websites).

Duponcheele, G., Fayémi, M., González Miranda, F., Perraudin, W., and Tappi, A. (2024). “Securitisation Reform to Boost European Competitiveness”, SUERF Policy Brief, No 976, September.

EC (2024). “Targeted consultation on the functioning of the EU securitisation framework”, European Commission, October.

EC (2025a). “Received contributions: Targeted consultation on the functioning of the EU securitisation framework”, European Commission, January.

EC (2025b). “Proposal for amendments to the Securitisation Regulation”, European Commission, June (also known as the Securitisation Package).

EP (2024). “Hearing of Maria Luis Albuquerque”, Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, European Parliament, November.

ESRB (2025). “Unveiling the impact of STS on-balance-sheet securitisation on EU financial stability”, European Systemic Risk Board, May.

FHFA (2015). “Overview of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Credit Risk Transfer Transactions,” Federal Housing Finance Agency, August.

JC of the ESAs (2025). “Joint Committee Report on the implementation and functioning of the Securitisation Regulation (Article 44)”, EBA, ESMA, EIOPA, March (also known as the JC Report).

Joulia-Paris, T., Saary-Littman, J., and Bearden, J. (2025). “In 2024, Private Risk Sharing through securitization increased by 37% in the EU and 16% globally, protecting € 21 bn of credit risk on € 260 bn of bank loans”, Report, International Association of Credit Portfolio Managers, July.

Ormezzano, V. (2024) “Basel III implementation: preserving EU banks’ capacity to finance the economy”, Note, Eurofi Regulatory Update, pp.85-94, September.

The traditional format involves the ‘true sale’ of a portfolio of assets to a special purpose vehicle (SPV), which then issues tranched exposures, most often, in bond format.

The synthetic format does not involve ‘true sale’ of assets into an SPV, referencing them instead. This format provides financing when capital relief is recognised.

In this note these expressions shall be used synonymously.

This is because Article 26e(8) of the Securitisation Regulation (SECR) does not list (re)insurers as eligible guarantors.

Unlike balance sheet investments, insurance contracts are considered a liability and are not subject to mark-to-market adjustments.

See point (aa) in Article 26e(8) of the Securitisation Regulation (SECR) proposed by the EC on 17th June 2025.

Source: “Survey Demonstrates Global Importance of CPRI”, International Association of Credit Portfolio Managers.

Source: “European Insurance Overview 2023”, Report, European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA).

Source: “Use of unfunded credit protection for synthetic SRT securitisations” in Supervisory statement 9/13, Securitisation: Significant Risk Transfer, Bank of England | Prudential Regulation Authority, July 2025 (Updating July 2020).

Source: “Credit Risk Transfer Progress Report. Fourth Quarter 2023”, Federal Housing Finance Agency, April.

Source: “2025 Scorecard for Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Common Securitization Solutions”, Federal Housing Finance Agency, February 2025.

Source: “Credit Risk Transfer Progress Report 4Q2023”, Federal Housing Finance Agency.

IACPM public survey results: https://iacpm.org/global-srt-insurance-survey/

Question 7.4 to 7.11 in EC (2024).

In one of the ‘cons’, the report states “Insurers would have a competitive advantage over other investors that still need to provide funding for credit protection for STS securitisations which would result in most of the credit risk of synthetic transactions ending up in the insurance sector.” Such statement is not informed on the basis of evidence, as can been seen by the (re)insurers’ small market share (less than 10%) in the market that is currently open to them on an unfunded basis, the non-STS one. Moreover, counterparty and concentration risks are by essence limited by banks themselves who have sophisticated credit mitigation frameworks and limit systems.

While concerns on counterparty and systemic risks can be mitigated with safeguards, to affirm that onboarding credit risk from banks creates policyholder protection concerns is a strange objection since being exposed to, underwriting and managing risk is the very purpose of insurance and a similar objection could therefore be made to literally every single risk that is the subject of insurance from life, to automobile, to artworks, to fire to catastrophe.

The ESRB report refers to CRR Article 249(3) that “introduces a cliff-edge effect, as a downgrade below the eligibility threshold would render the synthetic securitisation ineligible for both the STS label and SRT.” CRR Article 249(3) states: “[…] the eligible providers of unfunded credit protection listed in point (g) of Article 201(1), shall have been assigned a credit assessment by a recognised ECAI which was credit quality step 2 or above at the time the credit protection was first recognised and is currently credit quality step 3 or above.” Until 1st January 2025, all (re)insurers were in point (g).

Source: “Regulation (EU) 2024/1623 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2024 amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013”, Official Journal of the European Union, June 2024. (Known as CRR3).

The new CRR Article 201(1), in force since 1 January 2025 adds: « For the purposes of the first subparagraph, point (fa), of this Article, ‘regulated financial sector entity’ means a financial sector entity meeting the condition set out in Article 142(1), point (4)(b).” And this point (4)(b) includes entities within the scope of prudential consolidation group under the EU Solvency II Directive or equivalent: “the entity is subject to prudential requirements, directly on an individual or consolidated basis, or indirectly from the prudential consolidation of its parent undertaking, in accordance with this Regulation, Regulation (EU) 2019/2033, Directive 2009/138/EC, or legal prudential requirements of a third country at least equivalent to those Union acts;”

The external rating requirements that were duplicated in Article 202 for IRB banks for all eligible protection providers no longer apply, as this article has been repealed in CRR3. This article also required protection providers to “have sufficient expertise in providing unfunded credit protection”; the notion of ‘sufficient expertise’ is no longer present in the CRR.

Articles 100 (General provisions for SCR) and 128 (General provisions for MCR) of the Solvency II Directive (2009/138/EC)

The list of equivalent jurisdictions decided in 2015 should be updated. It is available here:https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/browse/regulation-and-policy/international-relations-and-equivalence_en

The loss of STS status leads to a marginal capital increase, without the creation of systemic risk. The loss of SRT recognition is different, it is the one that can create systemic risk.

SECR Article 26e(8) point (b) needs to cross-reference not only the current point (a) but also the new point (aa) (for (re)insurers).

Other techniques are reinsurance and replacement.

Annex 1 of the Solvency II Directive (2009/138/EC).

Article 112 (General provisions for the approval of full and partial internal models) and Article 113 (Specific provisions for the approval of partial internal models) of the Solvency II Directive (2009/138/EC).

The proposed text uses the term “assets under management”; we assume that the EC meant, like in the recital, to use the term “total assets”. Indeed, the best metric for assets of a non-life undertaking is ‘Total Assets’ which is available from the undertaking’s audited balance sheet, rather than ‘Assets under management’ which is a term not in use by non-life undertakings.

Interestingly, CRR Article 142, point (4)(a) defines the ‘large’ in a ‘large regulated financial sector entity’ and clearly refers to the parent company, dixit: “the entity’s total assets, or the total assets of its parent company where the entity has a parent company, calculated on an individual or consolidated basis, are greater than or equal to EUR 70 billion, using the most recent audited financial statement or consolidated financial statement in order to determine asset size;” The threshold of EUR 70 billion for ‘Total Assets’, a bank metric, was intended for banks. It is thus too high for most (re)insurers currently active in the non-STS market.

‘Resilient position’ is a new notion introduced in Securitisation Package for transactions with granular pools, sequential amortisation, and a senior tranche with sufficiently thick credit enhancement. The Proposed CRR Explanatory Memorandum (EM) conflicts with the Proposed SECR Article 26e(8) on eligible credit protection providers. Fixing the (EM) lets (re)insurers in STS securitisations to provide protection to transactions with ‘resilient positions’, which constitute most of the STS market. Not doing so, would restrict (re)insurers to ‘non-resilient’ STS deals —a small minority— and this would defeat the purpose of the reforms.