The views expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Deutsche Bundesbank or the Eurosystem.

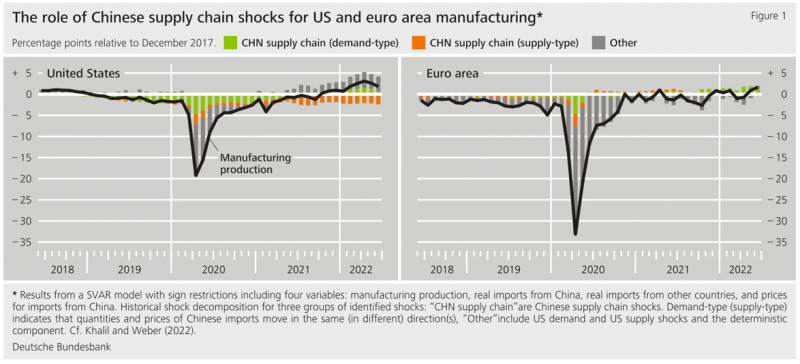

By using information on volumes and prices of Chinese imports, our approach differentiates supply-type supply-chain shocks, which are associated with delivery bottlenecks in the Chinese supply chain – for instance, due to containment measures in important industry hubs or ports – from demand-type shocks. The latter represent shifts of downstream demand away or towards goods with a high input content sourced from China. This includes policy-induced demand shifts, for instance the imposition of bilateral import bans or tariffs.

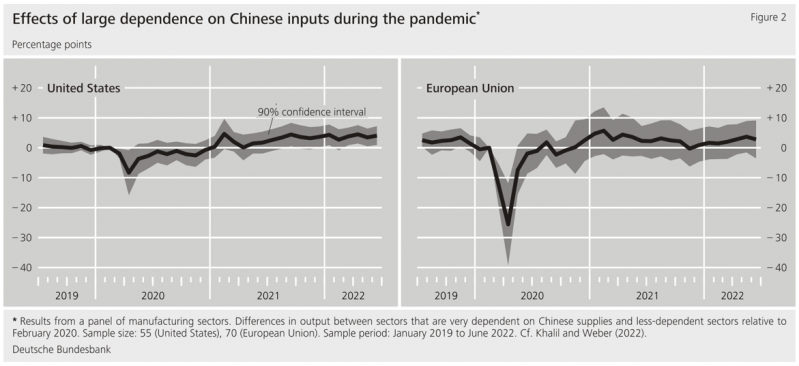

The early 2020 Chinese lockdowns hit US and European industries with a high dependency on Chinese imports particularly hard. This can be illustrated by a difference-in-difference approach à la Flaaen and Pierce (2019) in which we distinguish sectors with relatively high and low exposure to Chinese supply chains as measured by the cost share of Chinese inputs in production for manufacturing industries.1 As Figure 2 (left panel) shows, in April 2020 production in US manufacturing industries with above-median import exposure to China declined by almost 10% more than in industries with below-median exposure. The corresponding estimate for the European Union (Figure 2, right panel) is larger at more than 20%. In line with the results from the SVAR model, the effect was short-lived due to a fast reopening of the Chinese economy and the subsequent recovery of Chinese exports.

These demand-type shocks raised imports from China on the account of imports from other countries while leading to higher prices for Chinese imports. At the same time, manufacturing production in the US and in the euro area benefited. The exceptional pandemic-induced demand shift towards sectors that rely heavily on Chinese inputs (for instance electronics) fuelled supply-chain trade with China and supported the recovery of US and euro area manufacturing production.

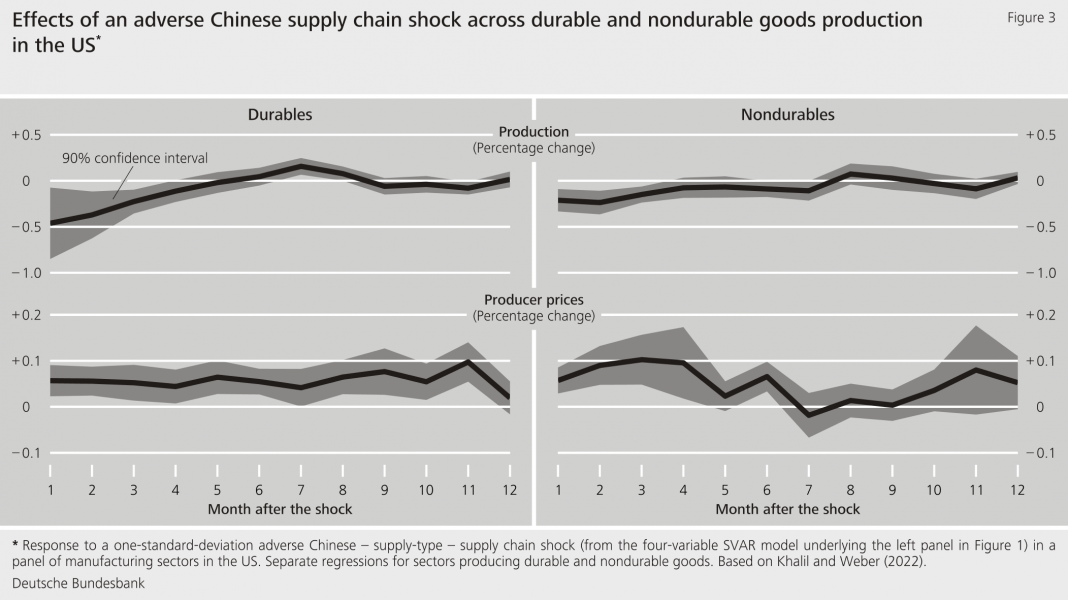

Especially manufacturing branches that produce durable goods suffer in terms of output losses. These branches are particularly reliant on Chinese supplies. Interestingly, although nondurable production uses relatively little Chinese value added, firms in both the durable and the nondurable sector increase prices to a similar extent. This suggests that storage – in particular the limited possibilities to store final goods in the nondurable sector – in addition to sectoral linkages plays an important role in the transmission of Chinese supply chain shocks to downstream producer prices.

Meier and Pinto (2020) and Lafrogne-Joussier, Martin and Mejean (2022) also employ different-in-different approaches to study the effects of the early lockdowns in China for the US and France respectively.