We would like to thank Johannes Hoffmann, Stephan Kohns and Arne Nagengast for their helpful comments and suggestions. The views expressed in this Policy Brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Deutsche Bundesbank or the Eurosystem. This analysis is based on data from Eurostat, Labour Force Survey (LFS), 2018. The responsibility for all conclusions drawn from the data lies entirely with the authors.

Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is expected to reshape labour markets, yet its impact differs across occupations and sectors. We link AI-exposure indices with microdata from the EU Labour Force Survey to assess potential sectoral relevance of AI automation for work in Germany, France, Italy and Spain. Exposure varies strongly: sectors dominated by manual tasks show the lowest exposure, while those with cognitive, especially non-routine analytical tasks, show the highest. The relative exposure pattern is consistent across countries. Using survey data on firms’ AI adoption in Germany, we find that sectoral AI use mirrors theoretical exposure indices. However, adoption correlates more with exposure of side skills than with core skills, suggesting that AI currently complements rather than replaces work.

The overall economic impact of AI is the subject of a controversial debate, particularly regarding its effects on work. AI usage can bring about significant structural changes in labour markets. Advancements in generative AI have raised concerns about potential job displacement. At the same time, it could also create new tasks and jobs through higher productivity.

We link AI-exposure indices with microdata from the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) to explore how the increasing use of AI could potentially impact work in different economic sectors across the four largest euro area countries. The choice of a sectoral perspective is not only justified by the limited empirical evidence at the industry level (see Calvino et al., 2024). Its relevance also stems from the macroeconomic implications of sectoral developments highlighted in the recent literature (see Filippucci et al., 2024; Aldasoro et al., 2024). However, as emphasised in Calvino et al. (2024), AI exposure may not necessarily reflect the extent to which firms actually use AI technologies. For this reason, we contrast existing AI exposure indices (Eloundou et al., 2024, Auer et al., 2024) with new survey data on firms’ AI use in Germany.

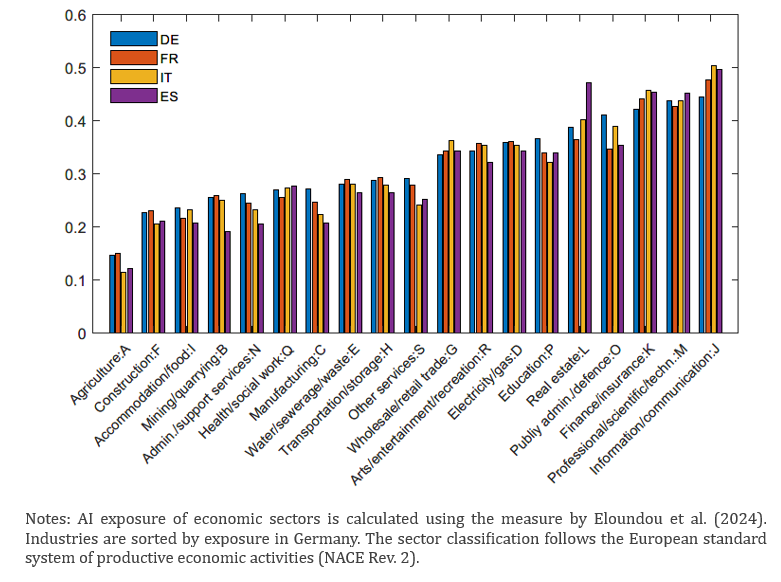

Figure 1. Sectoral AI exposure in the four largest euro area countries

Our starting point is the AI exposure index by Eloundou et al. (2024), which is increasingly used in the literature on the macroeconomic effects of AI (Filippucci et al., 2024; Acemoglu, 2025). This metric captures the share of tasks within an occupation classified as exposed to large-language models (LLMs) and partial LLM-powered software. Specifically, Eloundou et al. (2024) define exposure as the capacity of an LLM or LLM-powered system to reduce the time required for a human to complete a task listed in the U.S. Occupational Information Network (O*NET) database by at least 50% while preserving or improving quality.1

We link the information on occupational exposure with microdata for Germany, France, Italy and Spain from the EU-LFS, which provides information about the occupation of a surveyed person and the industry the person is currently employed in.2 In doing so, we implicitly assume that the task content of a specific occupation does not vary significantly either between the four largest euro area countries and the US or within the euro area economies.

By grouping this combined dataset by sector, we find that AI exposure differs significantly among various industries. In all four euro area countries, the “information and communication” sector stands out with the highest AI exposure (Figure 1). Relatively high AI exposure is also observed in “financial and insurance activities” and “professional, scientific, and technical activities”. On the other hand, the potential for AI to automate work activities in the sectors “manufacturing”, “mining and quarrying”, “accommodation and food service activities” and “construction” are notably lower at current AI capabilities. The “agriculture, forestry and fishing” industry shows the lowest AI exposure. This pattern is very similar across the four euro area economies. Since the AI exposure of a specific occupation is assumed to be the same in each country, differences arise from the fact that, within an economic sector, the concentration of specific occupational groups differs from country to country.

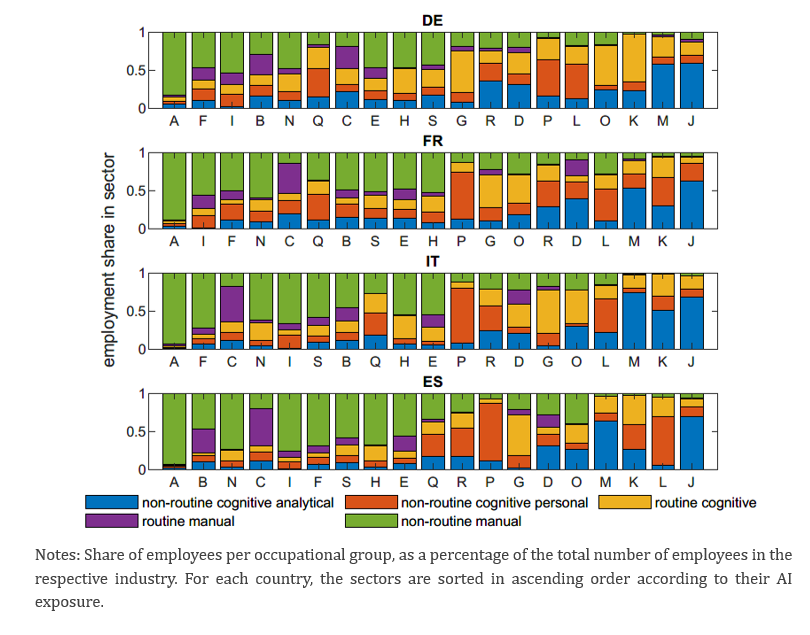

To enhance the analysis with an additional dimension, we follow the work of Acemoglu and Autor (2011), who use information from the O*NET database to categorise tasks into the five content groups: non-routine cognitive analytical, non-routine cognitive interpersonal, routine cognitive, routine manual and non-routine manual. To apply this sorting at the occupational level in the four largest euro area countries, we draw on the work by Lewandowski et al. (2020), who classify occupations by their dominating task content.3

The results show that sectors with significant AI exposure are dominated by occupational fields with a high proportion of cognitive tasks (Figure 2). In Germany, over 80% of employees in the three sectors with the highest AI exposure are engaged in occupations primarily involving cognitive work. A similar trend is observed in the other euro area countries. However, there are also differences between occupational groups labelled as “cognitive”. For instance, we find the average AI exposure of occupations with predominantly non-routine cognitive analytical tasks is noticeably higher than that of occupations with primarily non-routine cognitive interpersonal tasks. The lowest AI exposure is found in industries where manual non-routine tasks are predominant.

Figure 2. Sector-specific share of employees per occupational group

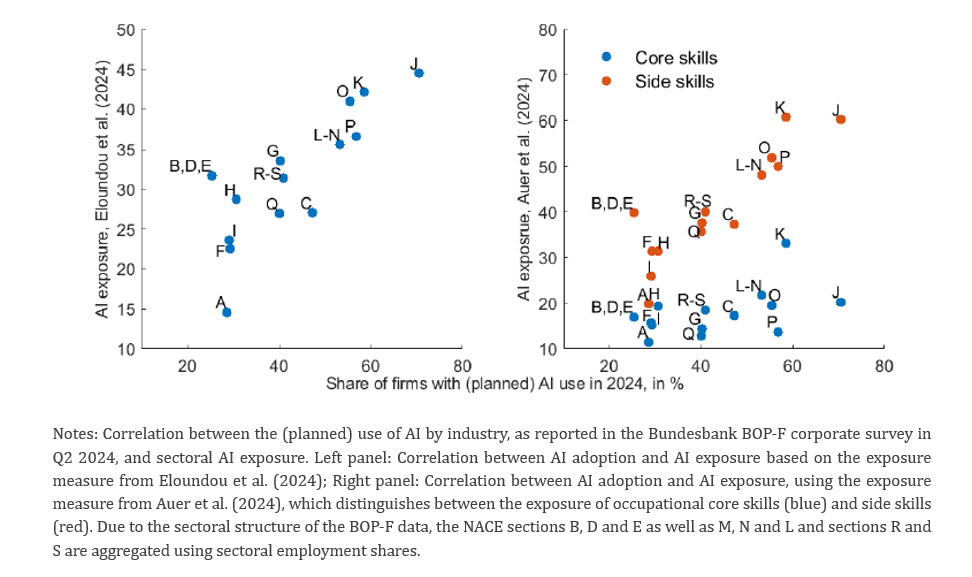

The AI exposure index by Eloundou et al. (2024) is designed to assess the potential impacts of an LLM or LLM-powered system on worker tasks. A natural question, especially from a policymaker’s perspective, is whether this assessment aligns with actual developments. Recent surveys conducted as part of the Bundesbank’s Online Panel – Firms (BOP-F) on the use of AI can offer valuable insights in this regard.4 As part of the BOP-F survey, German companies were asked in the second quarter of 2024 about their current use of generative and predictive AI. The results showed that over 40% of the firms already used the technology to a comprehensive, limited or experimental extent, or planned to implement it by the end of 2024 (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024). Looking at which sector the firms surveyed belong to, it turns out that the (planned) use of AI in the individual industries is strongly correlated with their respective AI exposure (Figure 3).

A more nuanced perspective emerges when utilising the AI Share Automatability (AISA) Index developed by Auer et al. (2024).5 Despite their methodological differences, the industries’ AI exposures are remarkably similar for the AISA index and the index from Eloundou et al. (2024). However, the AISA index offers more granular insights by allowing sub-indices to be derived for occupational core and side skills. This involves ranking the cognitive skills of an occupation by its importance and classifying the top third as “core skills”.

When analysing the relationship between the AISA sub-indices for core and side skills and actual AI adoption in Germany, we find that the correlation between current use of AI and AI exposure of occupational side skills is considerably stronger (Figure 3).

This observation is in line with the assessment that the technology currently tends to support employees rather than fully replacing them at the occupational level (see, e.g., Gmyrek et al., 2023; Bonney et al., 2024). It also fits with the fact that the intensity of AI usage among firms is still low in Germany. According to the BOP-F survey results, only 3% of German firms used AI comprehensively in 2024 (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024). Most firms reported only limited or experimental usage. It is important to keep in mind, however, that this is merely a snapshot in time, which depends, inter alia, crucially on the capabilities of AI. As outlined in Auer et al. (2024), the AI exposure of occupational core skills can increase significantly with the progress of AI capabilities.

Figure 3. Correlation of AI exposure and AI adoption in Germany

In our analysis, we present microdata-based evidence showing how different industries in the four largest euro area economies are exposed to AI-driven automation. Our findings show that the level of exposure varies significantly across sectors. Industries dominated by occupations that involve mainly manual tasks face limited AI exposure, while sectors with a high proportion of occupations requiring primarily cognitive tasks are far more affected, with non-routine cognitive analytical tasks being particularly susceptible. While exposure indices seek to capture the potential impact of AI, evidence from German firms confirms that sectors identified as having high AI exposure are already adopting AI more frequently. We further find that adoption is tied mainly to the exposure of occupational side skills rather than core skills, pointing to a complementary relationship with work at present. This, however, may be driven by the current phase of rather exploratory or limited AI use by firms. As AI capabilities continue to advance and the intensity of AI use rises, the exposure of core skills is expected to increase significantly in the future, implying that a complete substitution of human labour in certain occupational fields may become more probable.

Acemoglu, Daron. 2025. “The Simple Macroeconomics of AI.” Economic Policy, 40(121): 13– 58.

Acemoglu, Daron, and David H. Autor. 2011. “Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings.” In: Handbook of Labor Economics. Vol. 4, ed. David Card and Orley Ashenfelter, 1043–1171. Part B.

Aldasoro, Iñaki, Sebastian Doerr, Leonardo Gambacorta, and Daniel Rees. 2024. “The impact of artificial intelligence on output and inflation.” BIS Working Papers 1179.

Auer, Raphael, David Köpfer, and Josef Švéda. 2024. “The Rise of Generative AI: Modelling Exposure, Substitution and Inequality Effects on the US Labour Market.” BIS Working Papers 1207.

Bonney, Kathryn, Cory Breaux, Catherine Buffington, Emin Dinlersoz, Lucia Foster, Nathan Goldschlag, John Haltiwanger, Zachary Kroff, and Keith Savage. 2024. “The Impact of AI on the Workforce: Tasks versus Jobs?” Economics Letters, 244: 111971.

Calvino, Flavio, Hélène Dernis, Lea Samek, and Antonio Ughi. 2024. “A sectoral taxonomy of AI intensity.” OECD Artificial Intelligence Papers 30.

Deutsche Bundesbank. 2024. “The adoption and objectives of artificial intelligence in German firms.” Monthly Report December, 125–128.

Eloundou, Tyna, Sam Manning, Pamela Mishkin, and Daniel Rock. 2024. “GPTs are GPTs: Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models.” Science, 384: 6702.

Filippucci, Fabio, Peter Gal, and Matthias Schief. 2024. “Miracle or Myth? Assessing the Macroeconomic Productivity Gains from Artificial Intelligence.” OECD Artificial Intelligence Papers 29.

Gmyrek, Pawel, Janine Berg, and David Bescond. 2023. “Generative AI and jobs: A global analysis of potential effects on job quantity and quality.” ILO Working Paper 96.

Lewandowski, Piotr, Roma Keister, Wojciech Hardy, and Szymon Górka. 2020. “Ageing of Routine Jobs in Europe.” Economic Systems, 44(4).

Eloundou et al. (2024) provide several AI exposure measures at the occupational level based on the O*NET 27.2 database. We use their intermediate measure that captures the average share of all tasks within occupations that are exposed to LLMs and partial LLM-powered software, with the latter being scaled by 0.5, accounting for the fact that deploying the technology can necessitate additional investment.

The EU-LFS is the largest labour survey of European households. We match the exposure indices with the LFS data on ISCO 08 three-digit level. To do so, exposure indices are first aggregated from SOC six-digit level to ISCO-08 three-digit level using US employment weights by the Bureau of Labour Statistics. We use LFS data for 2018, a choice which is motivated by the relatively equal sample size across the four countries in that year. Results are robust when using more recent periods.

For instance, an occupation is classified as routine manual if the routine manual task intensity of that occupation is higher than the intensities of other task content indicators.

BOP-F is s a monthly representative survey of German firms conducted since June 2020, see https://www.bundesbank.de/en/bundesbank/research/rdsc/research-data/bop-f-618166.

Auer et al. (2024) calculate AI exposure indices for different levels of AI capability. We use the measure that assumes an intermediate level of AI capability of 3.6, the level for which, according to the authors, the mean AI exposure equals approximately the mean exposure in Eloundou et al. (2024).