The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

Our modern “polycrisis” brings myriad challenges, from climate change to inequality and institutional decay. These echo recurrent challenges faced by societies throughout history. While most past crises resulted in violence and institutional breakdown, a few rare cases managed to ‘flatten the curve’ and achieve stability through significant societal reforms. Scrutiny of these averted crises reveals three vital policy recommendations, highly relevant today: 1) reverse growing inequality and restore balance in material and social well-being; 2) expand state capacity by building strong fiscal and bureaucratic institutions to manage the demands of collective bargaining, welfare, and regulation; and 3) the most wealthy and powerful citizens must eschew the logic of short-term gain and maintaining status-quo privileges in favour of longer-term public stability. History suggests that structural reform, driven by powerful and willing institutions, is essential to mitigate looming social unrest and avoid catastrophic outcomes.

It is not news that societies all over the globe are experiencing myriad crises today, from global climate change to a major pandemic to runaway inequality, mass impoverishment, institutional decay, and rising sectarian violence. There is even a new term to describe the wicked problems we face: ‘polycrisis’ (Mark et al. 2025).

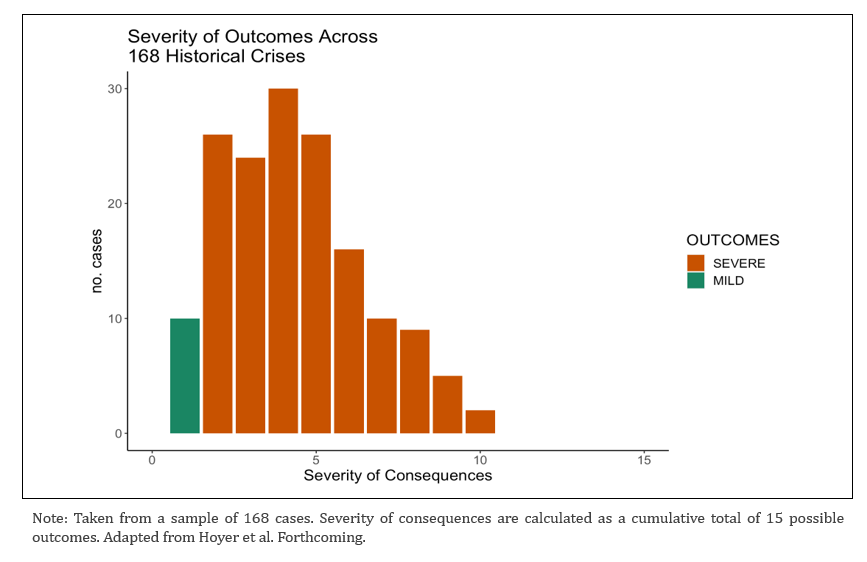

What may be surprising is that many of the crises we face today are not new but have actually been recurrent challenges since humans began to form large-scale societies over 6,000 years ago. As members of the Seshat: Global History Databank, we have been studying the dynamics of past societies for over a decade, including the challenges they faced. In a forthcoming study, we explore over 150 cases of societal crises past societies from all over the globe and across 4000 years of history (Hoyer et al. Forthcoming). Unfortunately, we found that in the vast majority of cases the outcomes were massive loss of life, the failure of critical institutions, civil war or even complete societal collapse. In rare instances, though, societies heading down the road to collapse managed to ‘flatten the curve’ of crisis, experiencing only relatively mild consequences. In fact, some of these societies even experienced apogees of stability and living standards in the following periods.

Figure 1. Distribution of the severity of outcomes from historical periods of crisis

We believe that there are important lessons to be learned from these past examples. This is indeed the focus of a new organization established by some of the authors of this article: SoDy (Societal Dynamics), the ‘historical policy lab’. Here, we summarize findings from a recent study of a few rare instances where the impacts of crisis were effectively flattened (Hoyer et al. 2025). We highlight the implications for national and international political and financial organizations looking to navigate similar risks in our modern polycrisis.

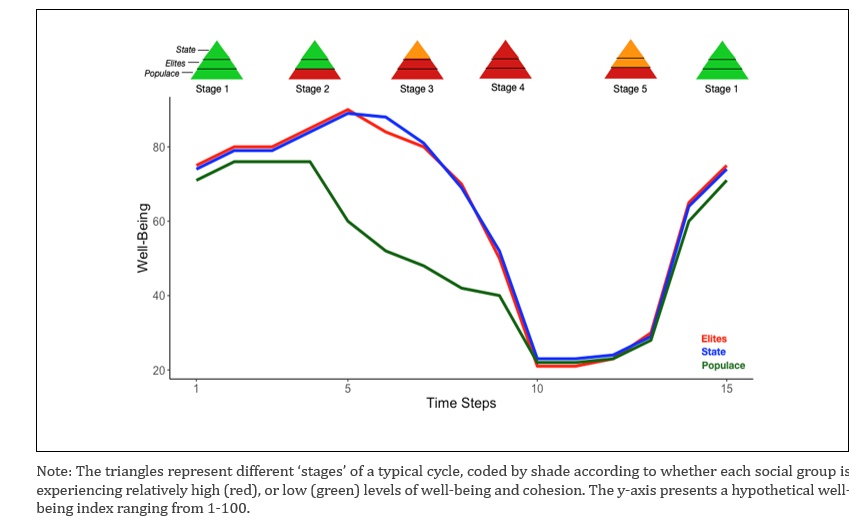

A common dynamic we observe in the way that crises unfold is that a relatively low degree of inequality perpetuates itself, growing more acute over time. Critically, this includes disparities in not only wealth and income, but also opportunity (e.g. to hold important political office or gain lucrative business positions) and access (e.g. to top-tier universities). We call this process the ‘wealth pump’ (Turchin 2023); effectively, those with relatively more power and means – elites or ‘1 percenters’ – use their positions to accumulate even more wealth and power for themselves and their children. Often, they tweak society’s rules and norms to turn the pump open further, such as lobbying for lower taxes on valuable assets. The next generation does the same, and so on until after a few decades the disparities between elites and the general populace is quite extreme. Clearly, this pattern holds in many modern societies as well as past ones (Hoyer 2025).

Such stark inequality is actually corrosive across the entire society. First, the majority population become immiserated, their quality of life diminishing as the cost of living grows beyond their means. Second, the greater the disparity in well-being that is allowed to develop, the higher of a premium becomes placed on being an elite, since the difference in lifestyle between that and non-elite is so stark. As more and more people gain more and more wealth, the fiercer they fight to get or stay in that rank, a phenomenon we call elite overproduction and conflict. At the same time, as these elites fight to capture the lion’s share of the society’s wealth, they tend to compromise state capacity and institutions which then prove ineffective, eroding people’s confidence and trust in government’s ability to resolve tensions and provide for their livelihoods.

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of a common societal crisis dynamic

(showing how well-being for different sectors of a society fluctuates over time)

Over time, these dynamics drive frustration, resentment, and fragmentation across societies. Left unchecked, the results in almost every instance we have seen are violent unrest, devastating civil war, and widespread misery (Turchin 2023). Unfortunately, there are signs of the same processes playing out in many wealthy countries today, including the USA. (Turchin 2024)

Yet some societies were able to avoid these spiralling crises, at least for a while. Our research into four such cases (Hoyer et al. 2025) suggests three key takeaways about how these societies responded to such crises that hold clear relevance to modern societies.

Without reversing, or at least slowing down, the wealth pump, inequality will increase and so the deep drivers of unrest and animosity between social groups will persist.

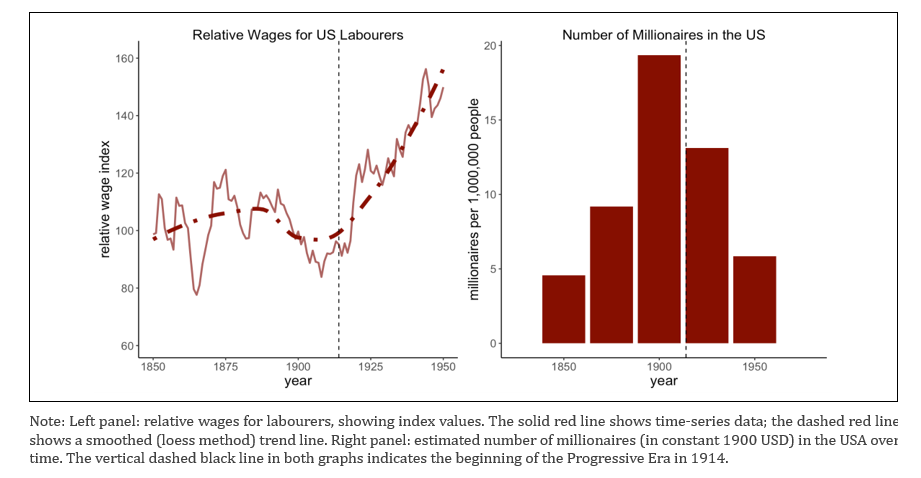

One of the clearest examples of how this can be done comes from the Progressive Era reforms made in the USA in the early 20th century. By the end of the 19th century, inequality in America had grown to extreme heights. We find all of the classic hallmarks of a looming catastrophe: large segments of the population faced diminishing real and relative wages (the difference between a labourer’s average wage and the GDP-per capita rate), unemployment was rampant, and many worked in largely unsafe and underregulated industrial factories. As expected, at the same time the number of millionaires skyrocketed as the share of the country’s income captured by elites ballooned. As state institutions struggled to manage these pressures, we find growing frustration in the form of increasing competition at top universities and a polarizing political climate.

Figure 3. Indicators of popular immiseration and elite overproduction in the USA

(before and during the Progressive Era)

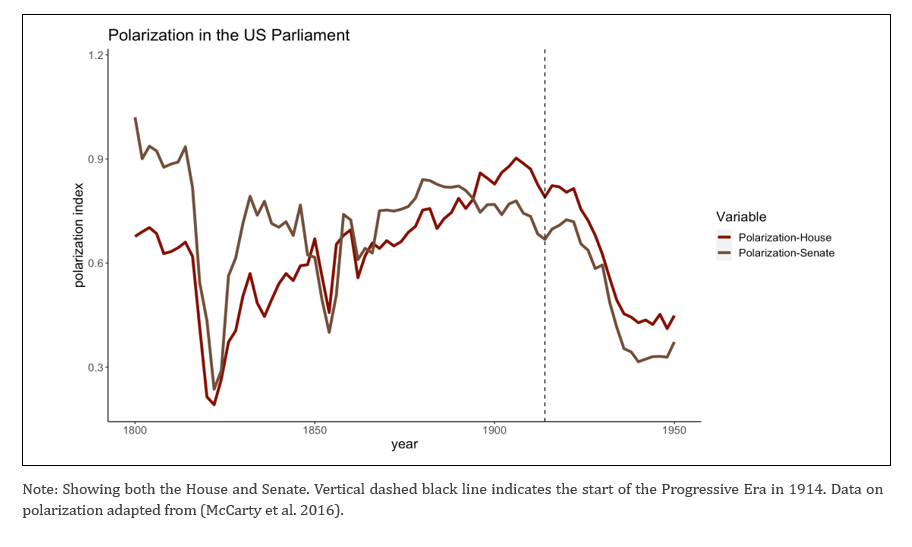

These tensions erupted as large-scale protests and civil unrest, some of which was met by brutal, violent crackdowns, including national armies being called in against striking workers in Colorado and elsewhere. Rather than spiral into a second bout of civil war, however, we see the country change tactics in the early 1900s. A powerful coalition of wealthy industrialists, including J.P. Morgan and John Rockefeller, and President Theodore Roosevelt started to push forward reforms aimed at alleviating the immiseration felt by industrial workers. Safety protections, wage guarantees, recognition of collective bargaining, and changes in university admissions policies all stand out as driving a critical turning point in the course of crisis.

In effect, the wealth pump was staunched. Fairly quickly, inequality was reduced and living standards improved for large segments of the population (though, critically, not everyone, which led to tensions re-emerging in subsequent decades). This period was critical in laying the foundation for the New Deal, during which then-president Franklin Roosevelt solidified and expanded these reforms, helping to minimize the impacts of the Great Depression.

Another critical commonality in cases of flattened crisis is the role played by the state. In the case of the USA in the Progressive Era and through the New Deal, we find federal laws and regulations catalyzing reform, from the creation of worker protections, such as the Federal Employer’s Liability Act of 1908 and the establishment of the National Labour Relations Board in 1933, to regulations on the banking and finance industries like the Glass-Steagall and Securities Acts, also in 1933.

Implementing these agencies and funding the social goods projects that became such an important part of America’s recovery during the Great Depression required a concomitant expansion of the government’s fiscal capacity. At the beginning of the Progressive Era, taxes were highly limited, as was the state’s role in economic and social life. The response to the burgeoning crisis required a transformation in both of these domains.

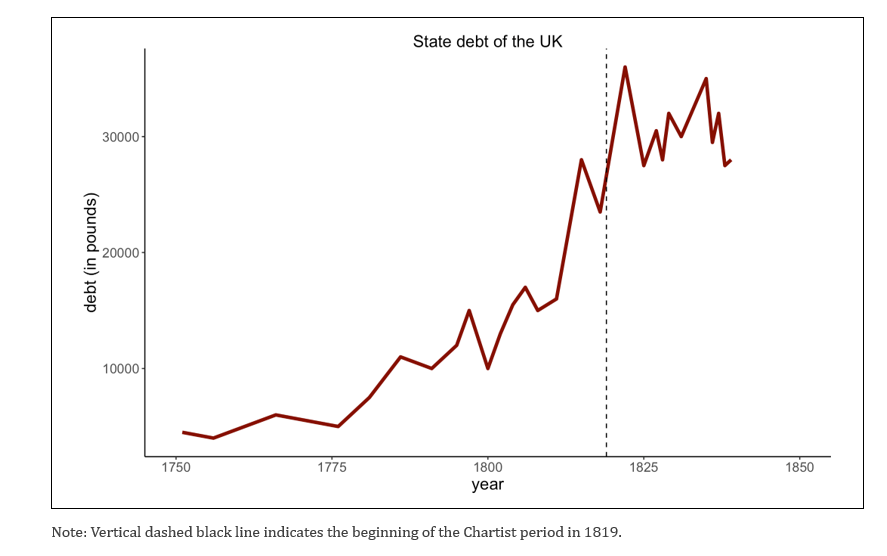

We find the same strong government response in another important case of averted crisis, the so-called Chartist Period in England during the mid-19th century. As in the American Progressive Era case, growing inequality and lack of regulation in England’s rapidly industrializing cities of the era led to extreme disparities in wealth, access, and quality of life. Despite controlling an extremely large and productive economy through their colonial territories, the United Kingdom’s debt was skyrocketing during this period as well due to the high costs of maintaining an empire and frequent warfare, coupled with low fiscal reach.

Figure 4. Estimated state debt in pounds of the UK in the late 18th to mid-19th centuries

And as in the case of the USA, we find a twin response where the British government, with the support of many wealthy and politically prominent citizens, implemented a suite of reforms aimed at protecting labour, providing alimentary support to impoverished citizens, and giving expanding political access and recognition of rights to different segments of the population (the franchise was extended a number of times, in 1832, 1867, 1869, and finally full enfranchisement in 1928, while slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire in 1833). At the same time, the UK’s fiscal and bureaucratic apparatus expanded to meet the demands created by these reforms and welfare programs, causing state debt to stabilize. However, it is important to acknowledge that these benefits were not seen uniformly throughout the British Empire, as deeply exploitative and authoritarian measures continued to be taken against indigenous populations in Canada, India, Southeast Asia, and throughout British territory.

A final trait we found is the importance of what we call ‘future thinking’, especially among political and economic elites. The ability of key power-holders to foresee an imminent crisis or at least recognize that legitimate frustrations are mounting among a growing segment of the population, can help push through the sort of institutional and structural reforms we see put into practice in these cases.

Support for meeting many of the demands sought by the Chartist protesters in England, and the change in tactics shown by political and economic leaders during the Progressive Era, switching from violent suppression to engaging in collective bargaining, show this clearly. In the American case, this coalition of many wealthy industrialists acting in concert with a set of prominent political figures from all ends of the political spectrum effectively relieved the partisan tensions that had been building in the late 19th century (even after the end of the Civil War in 1865).

Figure 5. Estimated levels of polarization in the US Congress over time

Having a fair amount of cohesion among a sizable coalition of elites willing to endorse major structural changes, even when it may require a (relatively small) sacrifice of some wealth and privilege, appears to be a critical component of successful, long-term crisis navigation. Indeed, all of the reform periods we have explored extended for long periods, several decades, and involved repeated interventions; these were not ‘one off’ policy packages. This willingness towards supporting reform is especially impactful if it comes while the state still has access to enough capacity to support these reforms, or at least to expand enough to meet the occasion. Unfortunately, the same cohesion also provides the means to suppress dissent and for elites to resist reforms, trying to hold on to their power and privileges by reinforcing status quo policies. This exposes a great irony of crisis dynamics: At the very point where reform is most needed, those with the greatest power to enact it are least inclined to do so.

Looking at cases where elite response to growing unrest was relatively repressive, resistant, and short-sighted highlights the significance of such future thinking. For instance, in another recent study, we look at the case of 14th-century Egypt (Holder et al. Forthcoming). Here again we find a build-up of inequality, immiseration, and frustration creating tears in the social fabric. At the same time, Egypt was beset by major floods, decimating the food supply, and the Bubonic Plague ravished the population. The response of the Mamluk government that controlled Egypt at this time, however, was to double-down on their authority, diverting large sums and labour to building massive monuments exalting the power of the rulers, rather than providing immediate relief to the suffering population. The result was catastrophe. Major civil warfare broke out, leading to the assassination of the Sultan and, not long after, the collapse of the Mamluk empire.

The specific circumstances of contemporary societies, and our modern polycrisis, are unquestionably different from those faced in the past. History doesn’t provide ‘plug-and-play’ solutions that can be applied uncritically in any context; indeed, the mission of SoDy is to translate historical lessons for modern circumstances. However, there are enough common patterns in how many societal crises are unfolding today to draw significant lessons from exploring the past.

The cases of societies flattening the curve on crisis outcomes suggest some critical principles for modern policy-makers. Notably, it appears incumbent on those with the greatest access to power, wealth, and authority to ‘future think’ and, thus, ‘future act’. Those with the most social power and vested interest in the status quo must be willing to give up some private, short-term gains for the longer-term public good.

This can come in a variety of forms, depending on the nature of the societies involved and how deeply the forces of societal stress and destabilization have taken root. But it is clear that our most powerful and influential institutions have vital roles to play:

Some of these represent major shifts in policy in many contemporary societies across the Global North. These will undoubtedly face heavy resistance from those who seem to be benefiting from the status quo. But history shows that this tends to be dysfunction, unrest, violence, or even societal collapse.

Holder, S.L., Ainsworth, R., Aldrich, D., Bennett, J.S., Feinman, G., Mark, S., Orlandi, G., Preiser-Kapeller, J., Reddish, J., Schoonover, R. and Turchin, P. Forthcoming. “The Spectrum of (Poly)Crisis: Exploring Polycrises of the Past to Better Understand Our Current and Future Risks.” (Preprint: https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/3bspg).

Hoyer, D., J. S. Bennett, H. Whitehouse, P. Francois, J. Reddish, D. Davis, K. C. Feeney, J. Levine, S. L. Holder, and P. Turchin. 2025. “CRISES AVERTED. How A Few Past Societies Found Adaptive Reforms in the Face of Structural-Demographic Crises.” Cliodynamics 15 (2): 1–50. https://doi.org/10.21237/C7clio.38365.

Hoyer, D. 2025. “The Rethink: Inequality—History’s Great Villain.” ASRA Network, May. https://www.asranetwork.org/news/the-rethink-historys-great-villain.

Hoyer, D., Holder, S., Bennett, J.S., François, P., Whitehouse, H., Covey, A., Feinman, G., Korotayev, A., Vustiuzhanin, V., Preiser-Kapeller, J. and Bard, K.,. Forthcoming. “All Crises Are Unhappy in Their Own Way: The Role of Societal Instability in Shaping the Past.” Journal of World History. (Preprint: https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/rk4gd).

Mark, S., S. Holder, D. Hoyer, R. Schoonover, and D. P. Aldrich. 2025. “Understanding Polycrisis: Definitions, Applications, and Responses.” Global Sustainability. Special Issue: Polycrisis in the Anthropocene, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2025.10018.

McCarty, N., . T. Poole, and H. Rosenthal. 2016. Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches. MIT Press.

Turchin, P. 2023. End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites and the Path of Political Disintegration. Random House.

Turchin, P. 2024. “Trump and the Triumph of America’s New Elite.” Bloomberg News, November 22. https://peterturchin.com/popular-article/trump-and-the-triumph-of-americas-new-elite/.