This policy brief is based on NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES, Working Paper 34382 . The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

Abstract

Public debt has surged globally in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. As governments face mounting pressure to consolidate budgets, public support for fiscal reform becomes critical. Yet, new cross-country evidence from a large-scale international survey reveals that citizens often misjudge debt levels, misunderstand fiscal mechanics, and anticipate personal losses from consolidation efforts. These perceptions are shaped by both cognitive biases and historical experience and pose considerable challenges for policymakers as they grapple with bringing debt down. This note synthesizes findings from a recent survey of 27,000 respondents across 13 countries with varying levels of public debt, highlighting the role of misperception, memory, and mistrust in shaping the politics of debt. It concludes with policy recommendations for improving fiscal communication and rebuilding public trust.

Public debt has soared to unprecedented levels across advanced and emerging market economies, driven by pandemic expenditures, structural fiscal pressures, and aging populations. In many cases, debt-to-GDP ratios have surpassed 100%, prompting governments to contemplate measures to consolidate budgets and safeguard fiscal resilience. The path to fiscal sustainability in democratic societies hinges not only on sound economic policy but also on public understanding and acceptance of necessary reforms. Misperceptions about debt and apprehensions over perceived inequities in burden-sharing risk fueling public resistance, potentially jeopardizing efforts to restore fiscal stability.

In our new study (Bianchi, Dabla-Norris, and Khalid, 2025), we leverage a comprehensive international survey conducted between April-May 2024, and spanning 13 advanced and emerging market economies with varying debt profiles, to address three critical questions shaping the politics of fiscal consolidation:

By examining these dimensions, our research sheds new light on the complex interplay between public understanding, trust, and the prospects for sustainable fiscal reform.

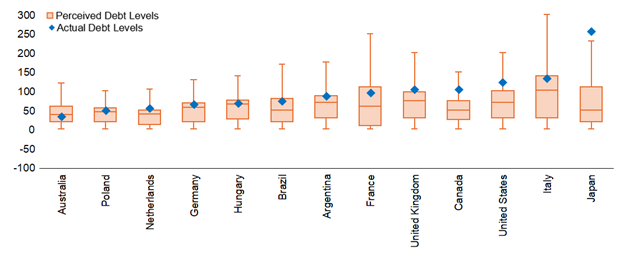

Recent cross-country survey evidence underscores a significant gap between actual government debt levels and public perceptions. Studies for a select group of countries by Roth et al. (2022) and Grigoli and Sandri (2024) document that citizens frequently misjudge the true magnitude of public indebtedness. Building on this literature, our international survey covers diverse economies such as Australia, United States, United Kingdom, Japan, France, Italy, Poland, Germany, and the Netherlands. We find that the accuracy of public perceptions is strongly correlated with a country’s debt burden. Notably, a majority of respondents systematically underestimate the debt-to-GDP ratio in their country, particularly in countries where public debt exceeds 100 percent of GDP.

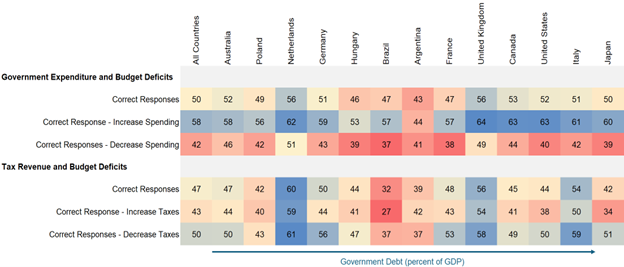

Moreover, basic fiscal relationships are poorly understood. Although almost half of survey participants recognize that a decline in tax revenues contributes to larger budget deficits, only 43% correctly associate increased tax revenues with reductions in deficits. When it comes to government spending, 58% are aware that higher spending increases budget deficits, yet just 42% understand that spending cuts help alleviate them. This disparity points to a prevalent “loss framing bias”: individuals tend to be more attuned to perceived losses than equivalent gains, a tendency widely observed in behavioral economics research.

Fiscal literacy is far from uniform across demographic groups. Our survey evidence reveals that older respondents and those with financial assets, such as savings or investment portfolios, consistently display a deeper understanding of public finance concepts. This pattern echoes the seminal findings of Lusardi and Mitchell (2014), who highlight the formative impact of life-cycle experiences on economic comprehension. Moreover, individuals who actively engage with traditional media and place a premium on staying informed about economic policies are significantly more likely to accurately assess fiscal relationships.

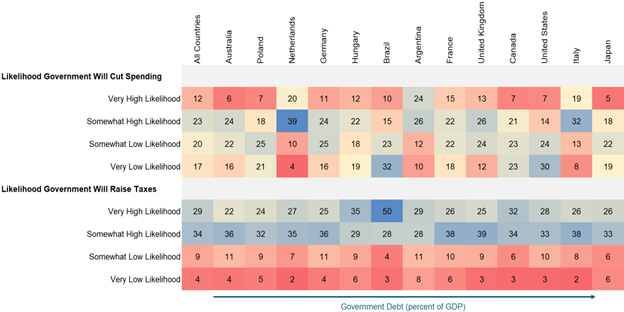

Despite limited fiscal knowledge, citizens are not indifferent to debt. When asked about future fiscal adjustments, nearly two-thirds expect tax increases, while only a third anticipate spending cuts. There are differences across countries in expectations of spending cuts: in the US and Brazil, around 30% of respondents assign a probability of less than 25% to spending cuts, while 24% of respondents in Argentina assign a probability of greater than 75%. These results are in line with Andre et al. (2022) who find that differences in associations across individuals and economic contexts may drive heterogeneity in beliefs.

Importantly, pessimism in policy expectations is self-referential: individuals expect to bear the brunt of consolidation. High-income respondents expect higher taxes on the wealthy and corporations. In contrast, middle- and low-income groups fear cuts to pensions, healthcare, and social programs compared to high-income groups. These expectations reflect a broader concern: that debt stabilization will disproportionately penalize “people like me.”

Such beliefs may explain resistance to reform even when fiscal consolidation is economically necessary. If voters perceive themselves as losers, they are less likely to support change, regardless of the macroeconomic rationale.

Figure 1. Respondents underestimate size of public debt in countries with high debt levels

Note: This figure shows the median and interquartile range for the response of people in each country to the question “What do you think the current level of government debt is in percent of your country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP)?”

Beliefs about government debt are shaped by context and experience. Building on a growing body of research and our international survey findings, we examine whether individuals’ previous encounters with fiscal consolidation influence their expectations about future tax and spending adjustments. Utilizing data from Adler et al. (2024), Escolano et al. (2018), and Alesina and Ardagna (2010), and following the methodology of Malmendier and Nagel (2011, 2016), we construct a measure reflecting each respondent’s exposure to past episodes of fiscal consolidation in their country. Because the historical data identifies only the occurrence but not the magnitude of these episodes, our measure is based on the frequency of consolidation events rather than their scale.

The results are revealing. Individuals who have lived through previous consolidation episodes exhibit a more pessimistic outlook on the effectiveness of fiscal actions in reducing debt. This is true irrespectively of whether such adjustments involved tax hikes or spending cuts. Individuals who have lived through consolidation are also more likely to view high current debt as harmful for future taxpayers and anticipate that elevated debt will require tax hikes or spending cuts. Exposure to consolidation also strengthens the belief that inflation could rise due to today’s debt levels. These results are also mirrored in respondents’ reported levels of trust in government, with a strong, statistically significant negative relationship between experienced fiscal consolidation and trust in government both across and within countries. These findings align with a growing body of research on experience effects, which shows that macroeconomic shocks leave lasting imprints on beliefs and behavior.

Moreover, the nature of past consolidation matters: exposure to spending-based austerity, in particular, fuels skepticism about the efficacy of fiscal policy and increases expectations of future cuts. This finding echoes Jacques and Haffert (2021), who show that spending cuts—more than tax hikes—erode government approval.

Together, these findings illustrate that personal and collective experiences with fiscal consolidation shape not only baseline beliefs but also attitudes toward future policy actions, often fostering resistance to reform when voters perceive themselves as potential losers. This experience-driven pessimism underscores the importance of understanding public sentiment when designing and communicating fiscal adjustment strategies.

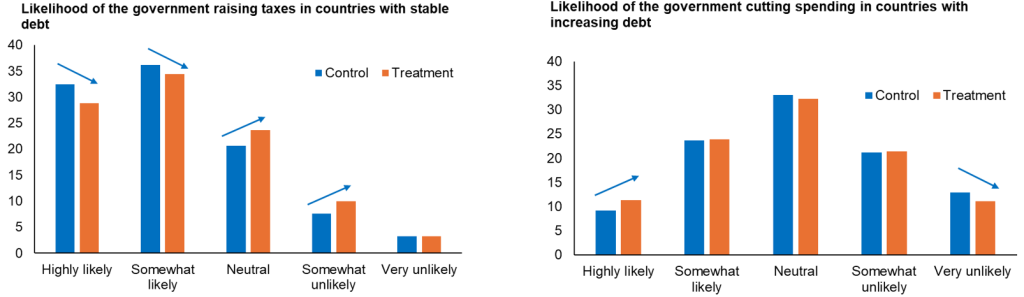

To test whether accurate information can shift beliefs, we conducted randomized information experiments. Respondents were shown actual debt-to-GDP ratios, explanations of fiscal relationships, and forecasts of future debt levels compared to a control group who received no such information.

The results are nuanced. In countries with stable or declining debt, correcting misperceptions—particularly among those who overestimated debt—leads to reduced expectations of future tax hikes. In contrast, in countries with rising debt, individuals who initially underestimated debt revise their expectations upward, but this does not change their expectations regarding tax increases (which start with high baseline priors), a finding that is consistent with Roth et al. (2022) for the US. This result is primarily driven by people with low initial qualitative and quantitative debt priors, suggesting that people tend to adjust their expectations of spending cuts when they are “surprised” by the high level of public debt.

These effects are moderated by experience. Individuals with greater exposure to past consolidations are more responsive to new data in countries with rising debt, suggesting that memory conditions how information is processed.

The findings underscore the importance of transparent and targeted communication around public debt levels, as accurate information can meaningfully influence public expectations and support for fiscal policy choices.

Figure 2. Respondents have limited understanding of basic fiscal relationships

Note: This figure shows the share of people in each country who correctly answered the questions “If government spending is increased/cut, what do you think is the impact on the government’s budget deficit?” (top panel), “If the government collects more/less tax revenues, what do you think is the impact on the government’s budget deficit?” (bottom panel). Correct Response represents all respondents who respond correctly to the question, regardless of the framing as increasing or decreasing.

Figure 3. Respondents’ expectations regarding fiscal policy changes in their countries

Note: This figure shows the share of responses in each country to the question “Given your knowledge of debt as a share of GDP in your country, what do you think is the probability that the government will increase the level of taxes or cut the level of government spending?”. Neutral is the excluded category. High includes over 50 percent probability, very high above 75 percent; low includes less than 50 percent probability. Shares reported for control group only.

Public perceptions of debt are shaped by both misinformation and memory. These beliefs influence expectations about taxes, spending, and inflation, ultimately affecting the feasibility of fiscal reform. To navigate the challenges of high public debt, governments must not only design sound policies but also manage public expectations.

This requires a strategic blend of communication, education, and engagement. Governments should invest in clearer, more transparent messaging about debt and fiscal sustainability. Just as central banks use forward guidance to anchor inflation expectations, fiscal authorities can use strategic communication to shape public beliefs. Fiscal councils and sound fiscal frameworks can play an important role here.

At the same time, one-size-fits-all communication strategies are unlikely to succeed. In high-debt countries, emphasizing spending discipline may resonate more than warnings about tax hikes. In low-debt contexts, clarifying the absence of imminent fiscal pressure can prevent unnecessary anxiety.

Only by bridging the gap between perception and policy can countries chart a sustainable fiscal path forward.

Figure 4. Information influences expectations regarding fiscal policy adjustment

Note: This figure shows the response to the question ” Given your knowledge of debt as a share of GDP in [your country], what do you think is the probability that the government will increase the level of taxes or cut the level of government spending?”. The figure on the left reflects the subsample of countries that have had stable or declining debt between the 2015-2019 period average and 2023. It further reflects the subsample of respondents whose prior qualitative beliefs regarding debt levels in their country indicated that debt levels are not low. The figure on the right reflects the subsample of countries that have had increasing debt between the 2015-2019 period average and 2023. It further reflects the subsample of respondents whose prior qualitative beliefs regarding debt levels in their country indicated that debt levels are not very high.