This policy brief is based on Banco de España Working Paper No. 2538. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

In Amado, Burga, and Gutierrez (2025), we explore how domestic banking regulations can generate real effects across borders – not through financial flows, but via international trade. We study a one-time, unexpected increase in loan loss provisions in Spain in 2012. We show that importers relying on the most affected banks experienced sharp reductions in credit supply, which led to a decline in their purchases abroad. This drop in demand hurt Spain’s trade partners by lowering their exports. The effect was stronger for countries with less developed financial systems, for exporters facing higher bilateral trade costs vis-á-vis Spain, and for products that are harder to reallocate across markets. Our findings highlight international trade as a key transmission mechanism of banking regulation–and domestic shocks more broadly–with implications for the cross-border coordination of prudential policy.

We exploit a 2012 reform in Spain that required banks to sharply increase loan loss provisions for real estate and construction credit.1 Importantly for our empirical design, the increase in loan loss provisions targeted a non-tradable sector — plausibly exogenous to the global economy — and was sizable, accounting for roughly 8.5% of Spain’s GDP. We combine this setting with comprehensive administrative data that includes the Spanish credit register, customs data, and bilateral global trade flows.

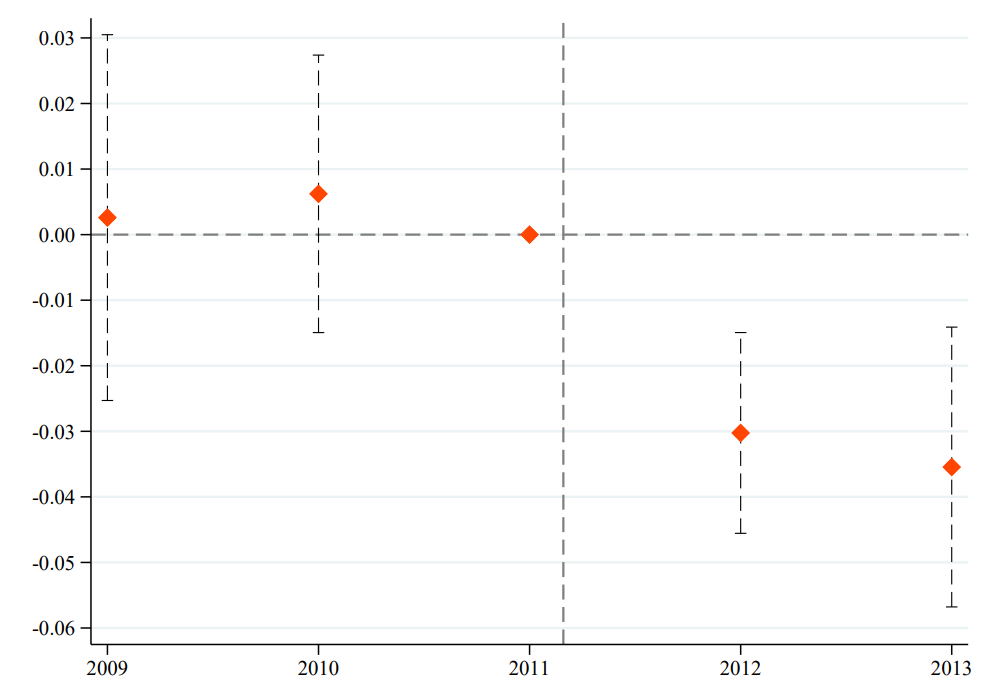

We use bank-firm level data from the Spanish Central Credit Register (CIRBE) to show that importing firms experienced 3% contraction in credit supply from banks most affected by the regulation.2 Importing firms were unable to mitigate the credit contraction by borrowing from less-affected bank credit, non-bank debt, nor equity. Thus, we find that exposed firms reduce imports by 3.6% and sourced from fewer countries.

Notably, the effects are more pronounced for riskier importers, those with weaker lending relationships, and those with limited access to credit lines. Moreover, importers that relied more heavily on supplier-provided trade credit before the policy were better able to smooth the credit contraction, suggesting that foreign suppliers played a role in alleviating the financial shock.

We then estimate whether this credit-induced reduction in firm-level imports aggregates up and is transmitted to other countries, or whether, alternatively, less exposed Spanish importers take over the market share of highly exposed ones (business stealing) leaving aggregate Spanish imports unchanged.

To do so, we use BACI data, which provides bilateral trade flows at the origin, destination, and product levels. This level of aggregation is necessary to test for potential business stealing across Spanish importers, which could suppress any cross-border transmission (Matray et al. (2025), Beaumont et a. (2025)).

We construct a measure of exposure to the policy at the product–country-of-origin level, capturing the extent to which Spanish importers of a given pair rely on funding from exposed banks. For example, if Spanish importers of textiles from India depend heavily on financing from highly exposed banks, then Indian textiles are highly exposed to the regulation. On the other hand, if Spanish importers of avocados from India depend on financing from unaffected banks, then Indian avocados are not exposed to the regulation. Then, we compare how the difference between Indian exports of textiles and avocados to Spain evolves before and after the policy, relative to the same difference when the destination is France. This specification allows us to control for multiple sources of confounding factors such as exporter and product level shocks.

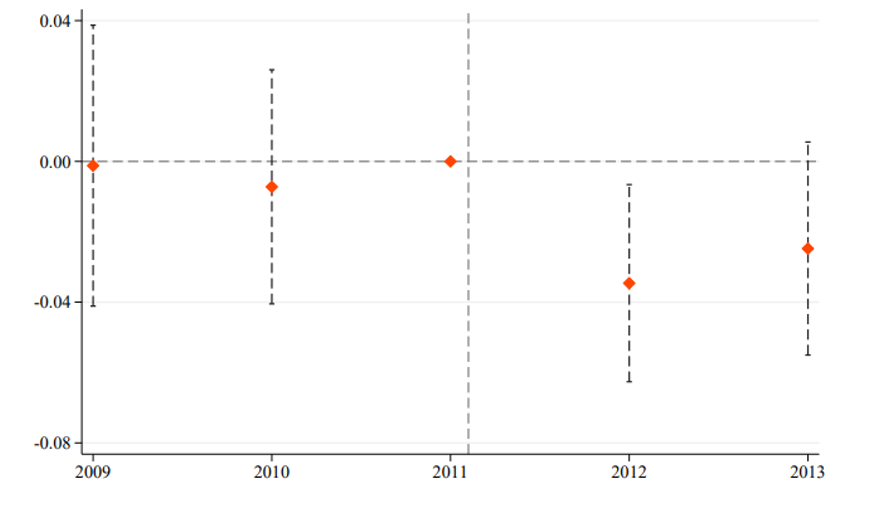

Our findings indicate that business stealing across Spanish firms is limited. Instead, we find a significant 2.1% decline in total exports to Spain relative to exports to other destinations of the same product and from the same origin.

Since we find no evidence of complete reallocation of imports within Spain, we proceed to examine how Spain’s trade partners reacted to the import demand contraction. First, exporters can mitigate a credit supply shock affecting their clients–Spanish importers–by providing financial support through more favorable trade finance terms, such as longer payment periods (Paravisini et al. (2014), Xu (2022)). This channel is consistent with our firm-level evidence on importers being more resilient when having supplier-provided trade credit, as discussed above.

We use our panel of country-product trade flows to study the role of financial development. We evaluate whether exporters operating in countries with more developed financial sectors–proxied by private credit to GDP–are better equipped to attenuate the Spanish credit shock by offering favorable trade finance terms. We find that exporters operating in highly developed financial systems fully offset the Spanish credit contraction, leaving their exports to Spain unaffected. By contrast, for exporters in countries with weaker financial development, exports to Spain shrink by 3.3%.

We next exploit variation in exporters’ trade costs to Spain to examine how these costs shape the ability of exporters in low-financially developed countries to attenuate the shock. We find that higher trade costs, captured by geographic distance to Spain and different language, generate stronger contractions in exports to Spain. While there are no significant effects for countries geographically close to Spain or for Spanish-speaking countries, exports from distant countries declined by 3.6%, and by 3.9% from countries that are both distant and non-Spanish-speaking. These findings indicate that higher trade costs exacerbate exporters’ difficulties in attenuating the credit-driven contraction in Spanish import demand.

Additionally, we find that the presence of Spanish banks abroad does not change the way exports to Spain respond to the Spanish financial shock. Instead, the spillover effects are mainly driven by how financially developed the exporting country is and by trade costs, rather than by multinational banking networks.

Spain’s trade partners may also respond to the contraction in Spanish import demand by reallocating sales to other destinations. We explore the role of reallocation frictions driven by product-specific characteristics. In particular, we compute a measure of product differentiation by calculating the 6-digit level product prices and calculating the dispersion at the 2-digit level. We define homogeneous products as those with low dispersion, and heterogeneous products as those with high dispersion.

We find that total exports of heterogeneous products fall by 9%, entirely driven by a 16% contraction in exports to Spain. By contrast, total exports of homogeneous products remain unaffected, as the decline in sales to Spain is fully offset by a significant increase in exports to other destinations. These findings highlight that product differentiation frictions constrain exporters’ ability to reallocate trade flows after a demand shock.

Overall, our findings suggest that tightening financial regulation – even when aimed at addressing domestic vulnerabilities–can propagate internationally by contracting import demand. Spain’s trade partners face two types of frictions in responding to demand shocks: attenuation frictions – which arise in financially less developed countries and are exacerbated by high trade costs vis-á-vis Spain – and reallocation frictions–which stem from product differentiation and limit the redirection of heterogeneous products to alternative destinations. These results highlight international trade as a central channel of regulatory spillovers–and domestic shocks more broadly–and underscore the need for both stronger financial development and cross-border coordination in prudential regulation design to minimize unintended disruptions to global trade.

Figure 1. Event-Study: average effect of the policy on firm-level Spanish imports

Note: For each year, the coefficient corresponds to the interaction of the firm-level exposure and the year dummy. The dashed lines indicate the 2.5%-97.5% confidence interval, with standard errors double clustered at the main bank and firm levels.

Figure 2. Event-Study: average effect of the policy on aggregate exports to Spain

Note: For each year, the coefficient corresponds to the interaction of the product-level exposure and the year dummy. The dashed lines indicate the 2.5%-97.5% confidence interval, with standard errors clustered by product and country of origin.

Amado, M. A., Burga, C., and Gutiérrez, J. E. (2025). Cross-Border Spillover of Bank Regulations: Evidence of a Trade Channel. Banco de España Working Paper No. 2538.

Beaumont, Paul, Adrien Matray and Chenzi Xu. (2025). “Entry, Exit, and Aggregation in Trade Data: A New Estimator”. Working paper.

Jiménez, G., Ongena S., Peydró J. L., Saurina, J. (2017). Macroprudential Policy, Countercyclical Bank Capital Buffers, and Credit Supply: Evidence from the Spanish Dynamic Provisioning Experiments. Journal of Political Economy, 125(6), pp. 2126-2177.

Matray, Adrien, Karsten Muller, Chenzi Xu and Poorya Kabir. (2024). “EXIM’s Exit: The Real Effects of Trade Financing by Export Credit Agencies”. Working Paper 32019, NBER.

Paravisini, Daniel, Veronica Rappoport, Philipp Schnabl and Daniel Wolfenzon. (2014). Dissecting the Effect of Credit Supply on Trade: Evidence from Matched Credit-Export Data. The Review of Economic Studies, 82(1), pp. 333–359.

Xu, Chenzi. (2022). “Reshaping Global Trade: The Immediate and Long-Run Effects of Bank Failures”. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(4), pp. 2107–2161.

See Jiménez et al. (2017) for an analysis exploiting the same regulatory intervention.

Measured as the pre-policy share of outstanding credit to the real estate and construction sectors