This SUERF Policy Brief is based on BIS Working Paper no 1308 “Environmental factors and capital flows to emerging markets”. The views expressed reflect those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Bank for International Settlements or the Central Reserve Bank of Peru. Any errors and omissions are our own.

Abstract

We study the impact of environmental factors on international capital flows – portfolio, bank, and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows – to emerging market economies (EMEs). Using two approaches, we first analyse how recipient country factors influence capital flows for 21 EMEs, finding that those with lower exposure to extreme weather events, a greener energy mix, and stronger climate-related policies attract greater inflows. Second, using bilateral data for FDI and bank flows, we explore the role of sending country factors (advanced economies, AEs). Stricter environmental regulations in AEs increase inflows to EMEs with weaker green regulations, suggesting an “emission shifting” effect, but also to EMEs with a greener energy mix. These findings underscore the importance of environmental factors in shaping international capital flows.

Environmental considerations – including climate-related issues, pollution and habitat destruction – are increasingly shaping public and private sector capital allocation. Emerging market economies (EMEs), which have historically attracted significant capital flows due to growth potential driven by industrialisation, urbanisation and higher returns, are now experiencing shifts in these flows due to environmental factors. Since the Paris Agreement, most EMEs have committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adopting climate policies, which have reshaped their macroeconomic outlook. Investors are aligning their strategies with these environmental objectives, redirecting resources towards sustainable investments.

This piece examines how environmental factors influence capital flows to EMEs, based on recent work where further details can be found (Aurazo et al (2025)). In addition to physical and transition risks, we also consider the recipient country’s energy mix, a previously unexplored factor in international finance.

Our analysis follows two approaches. First, we examine how environmental factors in receiving countries of capital flows affect foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio investment and bank lending. We do this for 21 EMEs with a sample ranging from 1996 to 2023. We find that EMEs with lower exposure to extreme weather events, a greener energy mix and stricter climate-related policies attract more capital, though the effects vary by type of flow. Second, we study how factors in sending countries shape bilateral FDI and bank flows, and how they interact with recipient country factors. This exercise covers 19 advanced economies (AEs) and 21 EMEs, from 2010 to 2023. The result show that stricter environmental regulations in AEs are associated with increased FDI and bank inflows to EMEs with weaker green regulations (an “emission shifting” effect) and to those with a greener energy mix. Overall, these findings highlight the growing role of environmental factors in shaping international capital flows and the interplay between conditions in both receiving and sending countries.

Environmental factors can affect capital flows through a variety of channels. First, physical risks and environmental degradation may damage assets, increase costs or render some activities less profitable, thereby deterring investment (Ehlers et al (2025)). Second, policies and regulations aimed at addressing environmental degradation and climate change can significantly influence capital flows (Gu and Hale (2023); Pienknagura (2024)). Finally, preferences for green energy could represent another channel, as the growing demand for environmentally responsible investments drives capital towards sustainable sectors, projects and countries (a driver not previously explored in the international finance literature). We found empirical evidence of the presence of these factors, with some differentiation by type of flows.1

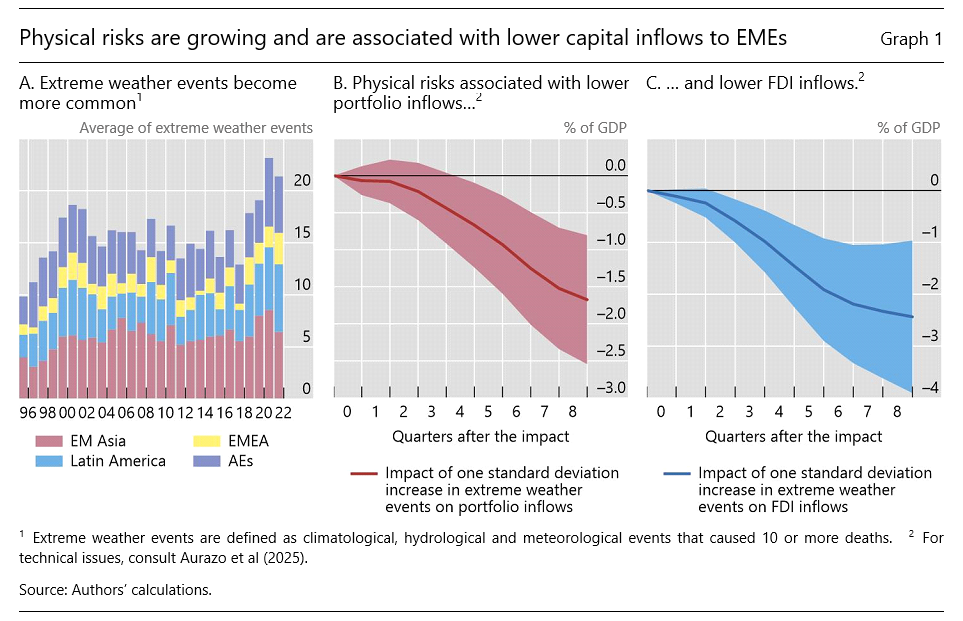

The globe is warming, and extreme weather events are becoming more common (Graph 1.A). Many EMEs, especially in Asia and Latin America, are strongly exposed to physical risks. For example, many Asian economic centres are close to the coast and prone to flooding. Building dykes or relocating activities will increase production costs and may not always be feasible. Most EMEs are in the hot regions of the globe, so further increases in temperatures can lower agricultural yields, increase cooling costs and reduce productivity of outdoor activities. At the same time, environmental degradation and physical risk may spur the demand for some goods and services. Global warming may also benefit some regions, even if the global effects are negative.

Physical risks can affect foreign investment in at least two ways:

We find evidence supporting the discouragement hypothesis. An increase in the number of extreme weather events is associated with lower portfolio and FDI inflows to EMEs (Graphs 1.B and 1.C) but has no statistically significant effect on bank flows. It appears that the effect is not immediate, as it takes some quarters for extreme weather events to discourage foreign capital.

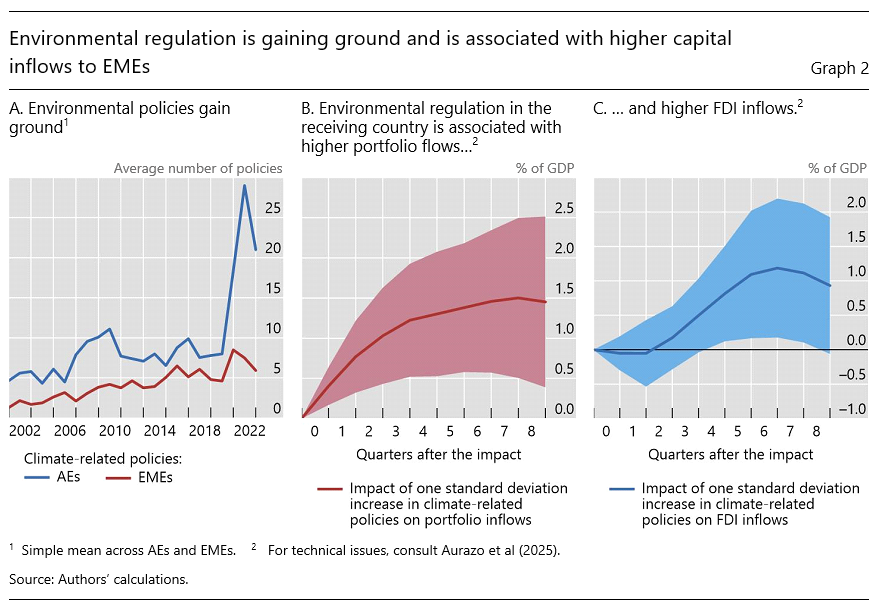

Climate-related policies have gained importance, initially in AEs but increasingly also in EMEs, in terms of both the number of announced policies and their stringency (Graph 2.A). These policies take a wide variety of forms, ranging from outright prohibitions of certain activities to quantity ceilings, taxes on specific emissions and emissions reporting requirements.

In contrast to the long-standing impact of physical risks, the effects of environmental policies, particularly those aimed at combating climate change, are likely to have become relevant only in more recent years. However, the impact on capital flows of environmental policies in the receiving country can be ambiguous, as these hypothesis are not necessarily mutually exclusive:

We find that, on the one hand, receiving countries with more environmental regulations tend to attract higher foreign investment. An increase in the number of environmental policies is associated with higher portfolio investment and FDI inflows after the number of such policies increase following the 2016 Paris Agreement, alluding to a “seal-of-approval effect” (Graphs 2.B and 2.C). We do not find any effect on bank lending.

On the other hand, in a bilateral flows approach, when we considered how environmental regulation in the sending countries affects capital flows, we found evidence that more environmental policies in the sending countries are associated with higher FDI and bank inflows. These results are stronger for EMEs with lower environmental regulations, leading to two important conclusions. First, this suggests that environmental factors in sending countries matter for capital flows to EMEs. Second, these findings suggest that “emission shifting” also plays a role in explaining capital flows to EMEs, complementing the “seal-of-approval” mechanism identified in the receiving country regressions above2.

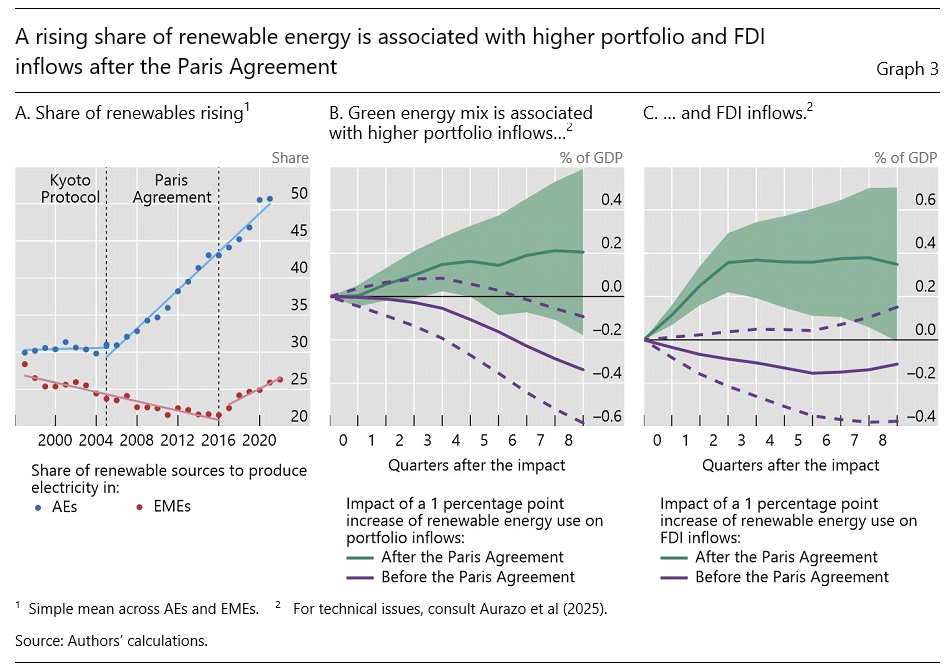

The Kyoto and Paris agreements were also followed by a sharp rise in the share of renewables in the energy mix of AEs and EMEs, respectively. Since Paris, the share of renewables in electricity generation in EMEs rose by approximately five percentage points to 27%, although this remains considerably below the 50% achieved in AEs (Graph 3.A).

A higher share of energy generated from renewables in the receiving country could help attract capital, as it would allow foreign investors or lenders to meet potential emission goals. This effect is expected to be stronger for sending countries with high levels of environmental regulation than for those with low regulation, indicating a larger presence of investors pursuing environmental goals. These observations lead to two clear hypotheses:

Our findings indicate that the greenness of the energy mix has become a significant determinant of capital flows only after the implementation of the Paris Agreement. Specifically, as shown in Graph 3, panels B and C, the association before and after the Paris Agreement reveals a significant change in dynamics. From 1996 to 2015, an increase in the share of renewable energy used to produce electricity in EMEs was negatively associated with portfolio inflows (purple lines). After the Paris Agreement, these patterns changed. We observe that an increase in the share of green energy is followed by higher portfolio and FDI inflows relative to the use of fossil fuel energies (green shades).

Finally, we examine the potential link between the energy mix of EMEs and the stringency of environmental policies in the sending country with bilateral FDI and Bank inflows to EMEs. As noted, stricter regulations in the sending country could channel more capital to EMEs with a higher green energy mix, as investors and lenders aim to align their portfolios with environmental standards and emission goals. We find consistent evidence that stricter environmental policies in the sending countries are associated with a higher growth rate of FDI and bilateral bank inflows to EMEs with a high share of renewable energy in their energy mix. These effects are larger and more pronounced in the longer term, suggesting that the benefits of a greener energy mix take time to materialise but can be more beneficial for capital flows to EMEs.

All told, this piece provides new evidence supporting our hypothesis that environmental factors (namely, physical risks, transition risks and the greenness of the energy mix) can influence the dynamics of international finance.

Aurazo, J, R Guerra, P Tomasini, A Tombini and C Upper (2025): “Environmental factors and capital flows to emerging markets”, BIS Working Papers, no 1308, 24 November.

Ehlers, T, J Forst, C Madeira and I Shim (2025): “Macroeconomic impact of weather disasters: a global and sectoral analysis”, BIS Working Papers, no 1292, 26 September.

Gu, G W and G Hale (2023): “Climate risks and FDI“, Journal of International Economics, vol146, no 103731.

Pienknagura, S (2024): “Climate policies as a catalyst for green FDI”, IMF Working Papers, no WP/24/46.

For technical aspects, data sources and the implemented empirical strategy, consult Aurazo et al (2025).

Results suggesting the presence of both channels also highlight the need for further empirical evidence on these emerging topics, particularly to quantify which of them might be dominant.