The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of their affiliated institutions. Note: The authors would like to thank Ellen van der Woerd for providing useful comments in the early stage of this paper and Sarah Liebing for providing useful comments. The authors would also like to thank the participants of the Payment and Settlement System Simulation Seminar hosted by the Bank of Finland and the Crypto Asset Monitoring Expert Group conference hosted by the European Central Bank.

Abstract

This note analyzes the stability of major USD-backed stablecoins using econometric models and recent market data. While stablecoins generally maintain their pegs and absorb volatility under normal conditions, they can transmit financial stress during crises, becoming more interconnected with traditional markets. The study recommends integrating stablecoins into regulatory frameworks, tailoring oversight to coin design, enhancing monitoring, and strengthening global coordination to mitigate systemic risks and support financial stability.

Stablecoins are digital tokens designed to maintain a stable value, typically by pegging one-to-one to a fiat currency like the US dollar. They promise the speed and efficiency of cryptocurrencies while supposedly offering the reliability of traditional money. Since their emergence in the mid-2010s, stablecoins have grown rapidly in use, facilitating billions in daily transactions across crypto markets and even attracting interest from mainstream financial institutions. Unlike volatile cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, stablecoins aim to hold a constant price (usually $1). However, despite their name, stable- coins are neither inherently risk-free nor “stable” under all conditions. Their stability relies on the soundness of their underlying reserve assets and mechanisms. If those foundations waver, due to market stress, loss of confidence, or operational failures, a stablecoin can lose its peg, as dramatically illustrated by the collapse of TerraUSD in 2022.

This policy brief summarizes recent research that examines the stability of major USD- backed stablecoins and their connections to the broader financial system. Using advanced econometric models on data from 2020 to 2023, the analysis investigates how different stablecoins respond to economic shocks and whether they could transmit or amplify stress in the financial system. The focus is on four prominent stablecoins USD Tether (USDT), USD Coin (USDC), Dai (DAI), and TrueUSD (TUSD), which offer a mix of issuer types and reserve structures. The key questions are: How do these stablecoins behave when markets turn volatile or interest rates change, and what are the implications for financial stability and regulation?

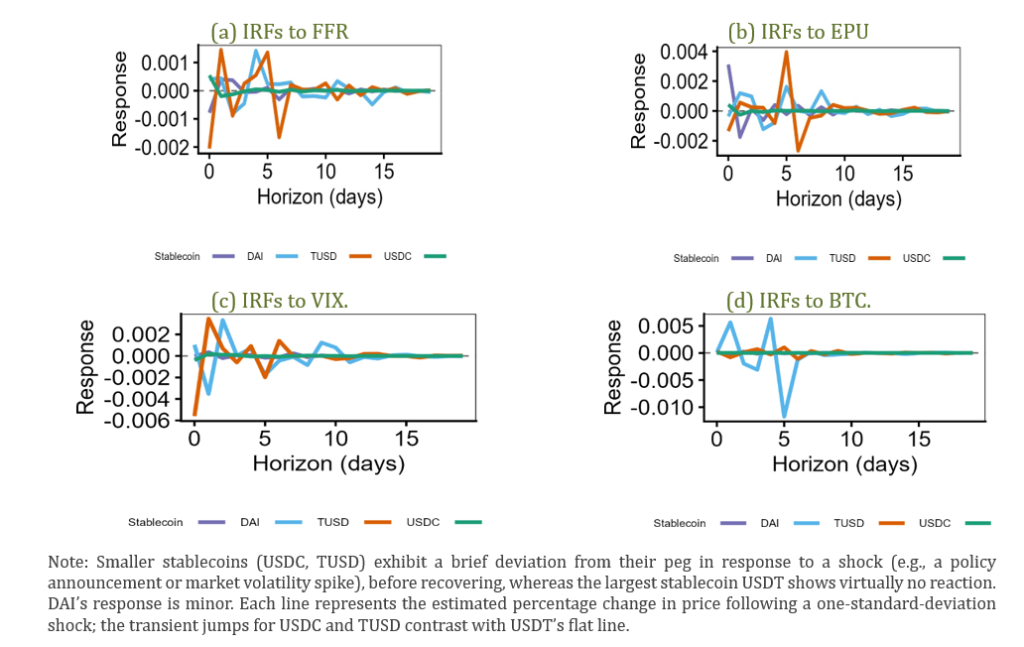

One way to test a stablecoin’s robustness is to see how it reacts to sudden economic or financial shocks. In the study, we simulate the impact of various shocks, including a spike in market volatility, a jump in economic policy uncertainty, a sudden interest rate hike, and a broad cryptocurrency market drop on each stablecoin’s price. The results reveal a clear heterogeneity in stablecoin responses. Two of the stablecoins, USDC and TUSD, exhibit noticeable but short-lived price movements following such shocks, whereas USDT remains essentially unfazed and DAI shows only modest, brief changes. In other words, a surprise event that causes turbulence in markets might make USDC or TUSD deviate slightly from their $1 peg for a short time, while USDT’s price stays virtually flat.

Notably, even for USDC and TUSD, the disturbances are temporary, any deviation from the peg tends to correct within a few days. Figure 1 illustrates this pattern: following a shock, USDC and TUSD prices dip or spike momentarily (indicating sensitivity to the shock) before reverting to stability, whereas USDT’s line on the graph is almost unchanged, reflecting a high degree of short-term resilience. DAI’s reaction is mild, suggesting it absorbs shocks better than USDC/TUSD but not as steadfastly as USDT.

These differences likely stem from variations in market depth, reserve confidence, and redemption mechanisms. Larger stablecoins like USDT, which dominates in market vol- ume, may have more liquidity and trust to buffer shocks. In contrast, smaller or newer stablecoins such as TUSD can be more prone to jitter when faced with sudden market stress.

The findings imply that not all stablecoins are created equal in terms of stability. Importantly, however, none of the observed shocks led to a runaway destabilization: even the more sensitive coins (USDC, TUSD) regained their peg rather quickly. This indicates that, in normal shock scenarios, stablecoins primarily act as volatility absorbers, they experience the impact of broader market swings but do not themselves exacerbate the situation for long. In effect, they can provide short-term liquidity to traders as a safe haven, but this safe-haven quality is stronger in some stablecoins (like USDT) than others. The resiliency of the largest stablecoin, USDT, suggests that market participants may view it as a reliably sturdy token for parking funds during uncertainty, at least in the short run.

Figure 1. Impact of sudden macro-financial shocks on stablecoin prices (using GARCH model)

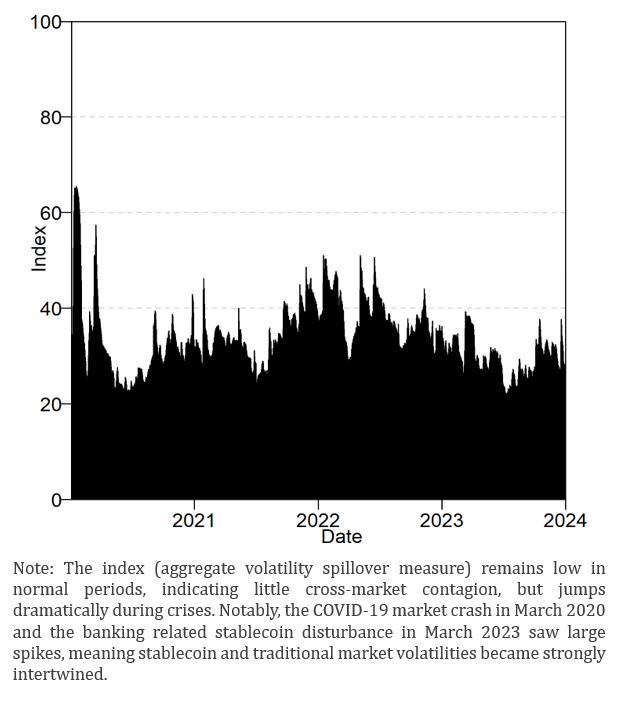

Beyond individual price stability, a key concern for regulators is whether stablecoins could serve as channels for financial contagion. Do stablecoins merely react to crises, or can they amplify and transmit stress across the financial system? To answer this, the research examined how intertwined stablecoins are with traditional financial markets over time, essentially mapping their “connectedness” with other assets and risk indicators. The analysis tracked a metric called the total connectedness index, which rises when volatility shocks are spreading widely between stablecoins, cryptocurrencies, and conventional markets (like stocks or interest rates), and falls when markets are compartmentalized.

The evidence shows that during tranquil periods, stablecoins behave largely as islands: their price fluctuations are mostly independent, influenced by their own demand and supply, and they have little effect on external markets. In fact, in normal times stablecoins tend to absorb volatility coming from outside (for instance, if stock markets swing or Bitcoin’s price gyrates, stablecoin prices might wiggle slightly in response, but they do not send significant shockwaves back into those markets). In technical terms, each stablecoin was a net “volatility receiver” rather than a sender under usual conditions. However, during major stress events, stablecoins become much more tightly linked with the rest of the financial system. In these moments, they can act as conduits of stress rather than just absorbers. Figure 2 shows how the connectedness index spiked sharply at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic turmoil in March 2020 and again during the financial market turbulence of March 2023. In March 2020, a global dash for cash hit virtually all asset classes, and stablecoins were no exception: even though their prices mostly held, the panic led to surging trading volumes and strains in liquidity that linked stablecoin markets with traditional finance. Similarly, in March 2023, when a shock in the banking sector (the failure of a major tech-focused bank) caused one large stablecoin (USDC) to temporarily lose its dollar peg, it underscored how trouble in traditional banking could instantly reverberate into crypto markets, pulling stablecoins into the fray.

These episodes demonstrate that stablecoins, despite normally being stable in price, are not immune to systemic crises. In calm times, a stablecoin might seem like a separate, contained tool for crypto traders. But in a crisis, stablecoins are swept up in the tides of financial stress, they become another node in the network of contagion. The analysis finds that since 2021, stablecoins have grown more interconnected with mainstream finance, likely as more institutions and investors engage with them. While stablecoins did not appear to trigger any crisis on their own during the study period, they transmitted shocks when they themselves or their reserve backing came under pressure. In practical terms, if confidence in a popular stablecoin were to falter during a market crunch, it could add pressure to other markets (for example, forcing fire-sales of assets in reserve portfolios, or impacting funding markets if firms rely on that stablecoin for liquidity).

Figure 2. Systemic connectedness of stablecoins with broader financial markets, 2020– 2023

Stablecoins have rapidly emerged as integral parts of the digital finance landscape. This study’s findings highlight a dual nature: on one hand, stablecoins generally succeed in maintaining stability and even buffer shocks under typical market conditions; on the other hand, they can become entwined with system-wide risks during extreme events. Policymakers and financial authorities should take proactive steps to bolster stability and reduce potential systemic risks associated with stablecoins:

In conclusion, stablecoins hold promise for more efficient payments and financial inclusion, but they also carry familiar risks in new forms. Prudent, targeted regulation and vigilant monitoring can help harness the benefits of stablecoins, speed and global reach, while keeping their potential downsides in check. With appropriate safeguards in place, stablecoins can be part of a resilient financial system rather than a “flip of the coin” in times of stress.