Opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the official viewpoint of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank or the Euro system. The authors would like to thank Natalie Glas and Susanne Hasenhüttl for valuable comments, even where perspectives may differ.

Abstract

Additionality asks whether financial interventions cause changes that would not have occurred otherwise. It serves as a litmus test for the credibility and impact of green or sustainable finance. Due to greenwashing, green bashing, and green hushing, this concept is more important than ever. Nonetheless, the concept of additionality is often overlooked in impact assessments and in the labelling of green investments. There are several reasons for this: (1) Measuring outcomes and establishing counterfactuals is difficult. (2) Financial institutions also avoid complexity that could hinder capital flows. (3) The slogan “doing well by doing good” misleadingly suggests that impactful green investments are easily feasible at market rates with normal risks. (4) Overemphasizing intentionality risks reinforcing the “warm glow” effect – feeling good with little real impact. (5) Amid lobbying pressure regulators shy away from strictly requiring impact investors to prove that their funds make a difference. This note aims to stimulate discussion about the need to ensure that green finance delivers a real and measurable impact on environmental sustainability and allocates scarce resources efficiently. Financial regulators should assess additionality in a structured, evidence-based, and context-sensitive manner. To promote transparency, they should incorporate this concept into their monitoring framework. Fiscal policy can increase the return or decrease the risk of green investments. For example, it can offer tax credits or loan guarantees to mobilize additional private capital for the low-carbon transition.

Investments under the umbrella of Green Finance are inherently tied to the question of impact.1 Take a company issuing a green bond to fund wind turbines: investors expect their capital to enable these projects. But if the company would have built the turbines anyway, the bond creates no additional impact. Thus, evaluating effectiveness requires comparing the actual outcome to a counterfactual asking: “What would have happened without the investment”. Only if the actual and hypothetical business as usual outcomes diverge can we speak of genuinely incremental green impact.

The financial sector can play an important role in advancing environmental goals, driven both by risk-conscious investors and by regulation.2 ESG ratings (Environmental, Social, Governance) can support this by assessing not just exposure to sustainability risks, but also the actual impact of investments (European Commission 2024). Our focus lies on this second aspect: impact. Interventions – whether financial or non-financial – aimed at achieving environmental outcomes must be examined for net impact to distinguish real change from misleading claims. At its most extreme, impact washing, (Busch et al., 2021) occurs when “impact” is used merely as a marketing tool without material results.

This article is not just about the narrow category of ‘impact investments’. Every investment has a non-financial impact, whether positive or negative, and should therefore be evaluated in terms of its sustainability implications. Our focus is on all strategies of sustainable investment, such as exclusion, ESG integration and engagement, as well as impact investment.

Non-additional interventions waste capital, at least in relative terms, since impact investors could have achieved results that align better with their preferences. Consequently, the green transition becomes more costly and less effective. Accordingly, Salzman and Weisbach (2024) perceive a double standard: rigorous additionality requirements are imposed on carbon offset markets, yet broader climate finance and policy instruments often lack such scrutiny. In the case of public environmental subsidies, similar deadweight effects are downplayed and referred to as windfalls. The authors advocate for the consistent and transparent application of additionality principles to effectively contribute to mitigation goals. Assessing impact also means evaluating all potential side effects (Busch et al., 2021). Interventions almost inevitably have unintended consequences, particularly in complex areas such as transition funding for fossil-heavy sectors. While these interventions can offer high-impact potential, misusing funds can result in negative outcomes. Therefore, rigorous monitoring and a clear impact framework are necessary to ensure interventions significantly contribute. Walkate and Paetzold (2025) criticize that the original purpose of impact investing – to cause change that would not otherwise occur – has been diluted. Many investors are attracted to the emotional reward of being seen as doing good (“warm glow”), often prioritizing labels and intentionality over actual impact. Often, impact is measured using methods that fail to capture additionality. This leads to investments in profitable, accessible markets that would have attracted capital anyway. This results in the repackaging of traditional investments as “impactful” without driving new or transformative change. Consequently, real additionality is overlooked, especially in less accessible markets or projects that don’t yet offer market-rate returns.3 To realign with the original goal, investors capable of concessional investments should focus on these underserved areas. Others can be engaged through subsidies or blended finance to meet their risk-return expectations.4 In the end, the focus should shift from attributing credit to oneself to emphasizing funding solutions for global problems.

Lam and Wurgler’s (2024) analysis of U.S. corporate and municipal green bonds shows that only 2% of proceeds fund projects with novel green features, with the rest used for debt or ongoing projects. They argue that investors do not reward additional-impact projects through pricing, index inclusion, or fund holdings, suggesting that green bonds serve as a labelling exercise rather than a mechanism for driving new climate benefits. Liang and Gao (2022) reviewed seven major green bond standards and revealed that only the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), and the European Union (EU) have explicitly discussed the issue of additionality, at least in supplementary documents. Importantly, none of the standards formally require the assessment or disclosure of additionality, highlighting a potential gap in ensuring that green bonds finance impactful environmental projects.

The EU’s sustainable finance framework, including SFDR, CSRD and Taxonomy, is showing signs of being diluted by lobbying efforts (Senn, 2025).5 NGOs and impact investors demand clearer evidence of real sustainability outcomes, but the industry favours flexible definitions to expand the market. Concerns include high compliance costs, legal risks, and a lack of standardized definitions. Consequently, they prefer voluntary frameworks, such as the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), which downplay additionality.

Although definitions of additionality may vary slightly depending on the context, there is a broad consensus that it “means that an intervention will lead, or has led, to effects which would not have occurred without the intervention” (Winckler et al., 2021).6 Confirming additionality requires answering three questions (Walkate and Paetzold, 2025):

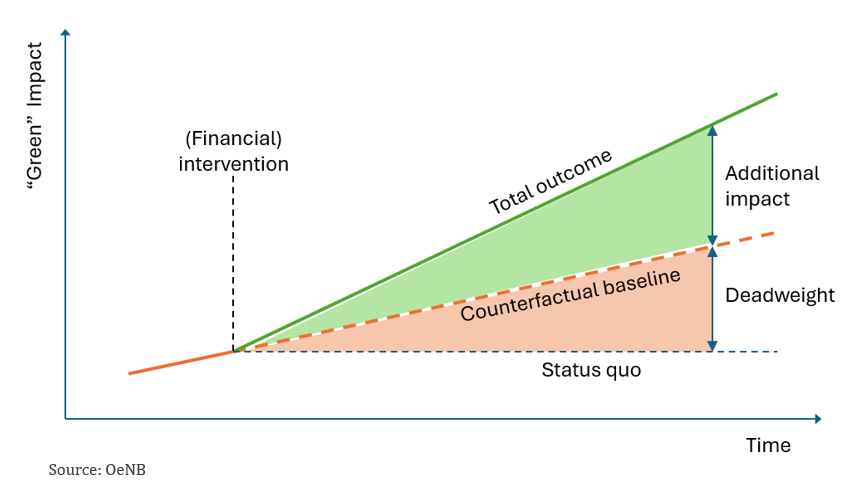

Therefore, an additionality check requires three elements: detection, attribution, and counterfactuality.” If a development simply follows the normal course of events without the investment altering that trajectory, such as enabling progress or preventing failure, then no real additional impact is realized. Furthermore, the outcome must be intended by the intervening party to constitute an impact. Figure 1 illustrates the scope of creating an (additional) impact. In this diagram, the “financial intervention” is an investment intended to achieve a positive environmental outcome within a specific timeframe (ILF Fund, 2020).

Figure 1. Additional Impact of a Financial Intervention

The counterfactual baseline (or reference case) is essential for assessing additionality. It represents the outcome that would have occurred without the financial intervention, driven by external trends, market forces, or other unrelated factors (business as usual). If the counterfactual and the observed outcomes are identical, then no additional impact has been achieved, meaning the intervention did not alter the expected trajectory. However, the counterfactual baseline should not be confused with the initial status quo. It reflects the projected change that would have happened anyway – the so-called deadweight – driven by factors other than the intervention. The following illustration tries to provide a better understanding for the sequence of steps connecting intention with impact.

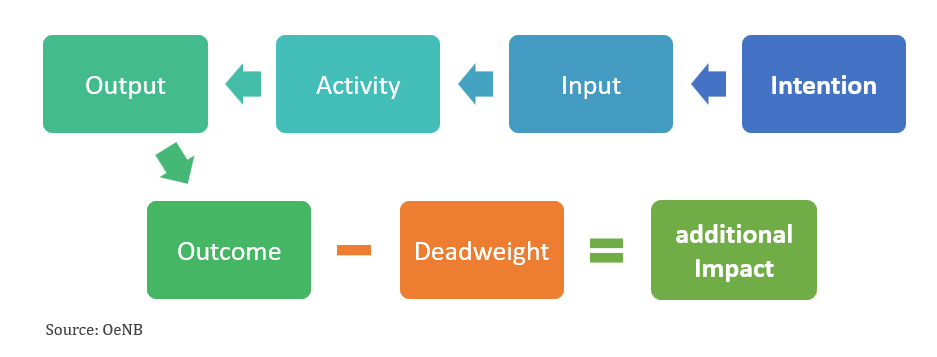

Figure 2. The Path from Intention to (marginal) Impact

This framework outlines a step-by-step process for assessing an intervention’s (marginal or net) impact (Simsa, 2014). First, identify the original intention (goals). Next, determine the concrete inputs – financial and non-financial resources – that enable activities. These activities result in outputs, such as services or products, which produce outcomes or broader effects on people or society. However, to determine the impact, one must subtract the deadweight, or outcomes that would have occurred anyway (Carr et al., 2008). The remaining impact is “what makes the difference.” While outcomes often appear at the societal level, more tangible outputs can also indicate meaningful impact, especially when broader outcomes are difficult to measure (Brest and Born, 2013).

The literature mentions different types of additionality. One key distinction is between financial and non-financial additionality (Impact Europe, 2023; World Bank Group, 2018). Financial additionality involves providing financing that the private sector would not offer independently or without displacement. Non-financial additionality is typically referred to as engagement or stewardship (Amjad et al., 2024; GSIA Alliance, 2023). In this case, investors play an active role in co-managing how funds are used, rather than simply allocating capital. Non-financial input, such as voting in shareholder meetings, is considered additional if it generates an outcome that would not have occurred otherwise.

Legal additionality involves evaluating whether a law or regulation – such as one that provides subsidies or establishes environmental standards – results in new, positive outcomes. When defining additionality, it’s crucial to link inputs to outputs because impact is ultimately measured by outcomes (Gillenwater, 2012a). Properly assessing causal effect requires connecting the input (e.g., a subsidy or regulation) to the outcome (e.g., reduced emissions or increased renewable energy use). Therefore, the baseline should be defined in terms of the outcome rather than the input, except in specific cases such as blended finance, where input-based assessments may be relevant.

Defining this baseline is a central challenge in impact and additionality assessments since it is never directly observable. The outcome linked to the intervention as well as an alternative scenario without the intervention are always unknown before the intervention. From an ex-post perspective, the counterfactual scenario remains hypothetical. The extent of speculation constitutes an important concern with respect to the additionality criterion.

However, uncertainty is a common problem in any cause-and-effect relationship. This challenge is not reason enough to ignore the issue of additionality altogether. Even without exact statements, it is important to understand the context as well as possible and evaluate the impact of activities using available tools outlined in Section 5. Also, more general, context-related considerations may justify an intervention by analysing various scenarios. The question of additionality is essential for the effective use of resources in order to sustain or enable positive impacts and minimize negative ones. Nevertheless, if it is impossible to fully clarify what exactly makes the difference, that should not be a reason to completely eliminate funds (Salzman and Weisbach, 2024). It is more important to analyse how the funds will be used in the future and adjust as necessary.

Due in large part to public budget constraints, private financing plays a significant role in achieving green finance goals, especially in mobilizing capital for climate mitigation and adaptation.7 Green bonds, sustainability-linked loans, and institutional investments are recognized as important contributors to environmental goals (Salakhova, 2023; Bhutta et al., 2022). However, the true impact of these interventions remains uncertain without the lens of additionality. This is particularly relevant in impact investing, which aims to generate specific outcomes and intends to generate social or environmental benefits alongside financial returns.

The literature identifies two broad types of impact-linked strategies (Busch et al., 2021):

With impact-aligned investments, no specific intention is actively pursued through the investment. While applying negative criteria avoids certain environmentally harmful assets, achieving a measurable positive impact is secondary. The same applies to ESG investing, which focuses on managing risks rather than achieving specific outcomes. However, when an investment sets a clear goal, such as reducing emissions by a certain amount, without specifying the inputs, it becomes more difficult to prove additionality credibly. This challenge applies to instruments like transition bonds and sustainability-linked bonds, which often claim to have an impact but may not provide clear evidence of it.

While frameworks in impact investing in a narrower sense emphasize intentionality and measurability, some tend to avoid the question of whether the impact would have occurred without the investment (Füllgraf, 2023; DVFA, 2023). Organizations like the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) promote responsible practices but do not include additionality in their core definition. As a result, investments may align with sustainability goals but fail to demonstrate that they caused new or different outcomes. Even so, the counterfactual scenario – what would have happened without the intervention – is rarely made explicit. This absence weakens the case for marginal impact and raises the risk of impact washing or purpose washing, where investments claim environmental benefit without demonstrating causality (Findlay & Moran, 2019).

Blended finance is the strategic use of public or philanthropic capital to mobilize private investment for sustainable development goals, particularly in environmental and climate-related sectors (OeEB, 2021). Although its roots lie in development finance, the approach is now being used in various public-private partnerships (PPPs) beyond investments in the Global South (Escalante et al., 2018). The core idea is to leverage limited public funds to attract larger sums of private capital that would not otherwise be invested in high-risk or low-return projects. This principle refers to financial additionality (IFC, 2018).

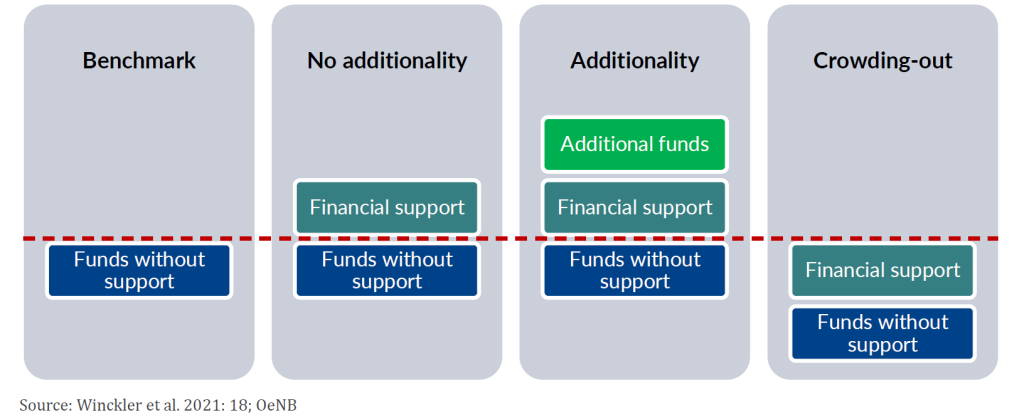

Blended finance can bridge critical financing gaps for green projects, including renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and climate resilience infrastructure. Development finance institutions and multilateral development banks play a key role in this area (Winckler et al., 2021; IFC, 2018). These institutions offer concessional loans, guarantees, and equity co-investments to reduce perceived risks and incentivize private sector participation. Ideally, their interventions will attract private finance, creating additional investment flows and delivering long-term development and environmental benefits (Winckler et al., 2021; Escalante et al., 2018). The European Investment Bank (EIB), for instance, uses its Additionality and Impact Measurement framework. It follows a project-by-project, ex-ante evaluation of the expected societal impact, starting from the intended outcomes and tracking inputs and outputs through a logical results chain. The goal is to guarantee that every public euro spent results in outcomes that would not have occurred otherwise (Küblböck and Grohs, 2020). Figure 3 illustrates this objective.

Figure 3. Evaluating financial additionality in blended finance operations

Critics warn that blended finance could result in a crowding-out effect, where public funds displace – rather than supplement – private investment. If not carefully designed, public support may subsidize ventures that would have proceeded anyway, eroding the principle of additionality. Furthermore, the lack of standardized definitions across institutions creates inconsistencies (Küblböck and Grohs, 2020). For example, some define additionality as exclusively private capital mobilization, while others include public co-financing. One key methodological challenge therefore remains balancing optimal financial support to maximize private investment without excessive public subsidy or inefficiency.

Similar to blended finance, carbon offsetting – whether voluntary or regulatory – relies heavily on the credibility of additionality claims. The basic premise is that emissions reduction in one place can offset for emissions elsewhere (Perspectives, 2023). However, this only works if the reduction is truly additional (McFarland, 2024). Without additionality, carbon credits merely shuffle responsibility rather than reducing global emissions (Gillenwater 2012b). Leading frameworks, such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) use multi-step methodologies. They assess additionality by evaluating if a project can financially survive without carbon offsets, faces non-financial barriers it couldn’t overcome alone, and goes beyond what is commonly practiced in its sector or region (Du Monceau and Brohé, 2011; Perspectives, 2023). They include standardized baselines and discount mechanisms for risks such as wildfires (Verra, 2025).

These processes are more structured than those in blended finance, with established baselines, verification standards, and third-party audits. Nevertheless, serious credibility issues remain (Downey, 2022). Research shows that many projects approved under CDM would have occurred without carbon revenue and thus fail the additionality test (Du Monceau and Brohé, 2011). Issues like weak baselines, lack of permanence, leakage, and the moral hazard of continued emissions under the guise of compensation have triggered strong critiques of the offsetting market (McFarland, 2024). Despite methodological rigor, offsetting remains vulnerable to manipulation and system-level ineffectiveness, especially when additionality is treated as a checkbox rather than a robust causal claim.

Assessing additionality is inherently difficult, as it requires imagining and comparing against a hypothetical and unobservable counterfactual. To improve our ability to assess additionality, it is essential to understand the different dimensions through which impact is realized: direction, time, scale, and purpose.

Impact can be positive or negative, direct or indirect, and vary in scale. Clearly, we focus on positive environmental impacts, such as reduced emissions and improved energy efficiency. Direct impacts, such as retrofitting buildings, are easier to observe and measure. Indirect impacts, such as influencing consumer behaviour or policy, are harder to trace and verify. Micro-level impacts may be quantifiable, but macro-level outcomes involve many actors and variables, making attribution difficult. The farther removed the effect is from the original intervention, the harder it is to prove causality.

Impact is dynamic; it unfolds over time. Short term effects like project implementation or immediate emission savings may be observable and linked more clearly to the intervention. However, long-term impacts are more difficult to pin down. Societal shifts, ecological recovery, or behavioural changes may take years or decades. During this time, intervening variables multiply, making it much harder to isolate the role of a specific (financial) intervention. Moreover, long time horizons complicate the definition of a baseline scenario, which is critical for additionality claims. Despite those challenges, positive long-lasting outcomes are what we’d wish for in the context of sustainability. In this sense, additionality may reduce over time even if the positive consequence persists. It just becomes harder to trace it back to specific interventions (Impact Frontiers, 2025a).

Another key concept is path dependency. Early interventions – such as investing in green infrastructure – can lock in future decisions, shaping or limiting subsequent options. The earlier and riskier the intervention, the more likely it is to be additional. As projects mature and benefit from economies of scale, the marginal benefit of new funding often diminishes. In this context, additionality tends to decrease over time, as productivity becomes self-sustaining. As Antonioli (2024) argues, we should ask: “How long is additional support needed before a project can stand on its own?”

Impact is defined relative to intentions and goals. In green finance, these goals often focus on addressing climate change, though the terminology can vary: green, sustainable, carbon, and climate finance are sometimes used interchangeably (Bhatnagar and Sharma, 2022). As Babic (2024) cautions, overly broad or narrow definitions should be avoided. The key is to focus on the specific environmental or societal goals being pursued.

ESG frameworks provide a set of targets. However, ESG mainly assesses firm-level performance. True impact, and thus additionality, requires considering external effects on society and the environment.8 While this shift in focus increases complexity, it is essential for meaningful green finance assessments.

We conclude that assessing additionality is methodologically challenging due to the need to prove a counterfactual and consider multiple dimensions of impact (EIB, 2025). Nevertheless, additionality remains a critical concept, as it is essential for distinguishing impactful finance from actions that would have occurred regardless. Clearly defining and considering the direction, scale, time horizon, and purpose of impact can help build more credible frameworks for assessing additionality. Although uncertainty is unavoidable, a structured, multidimensional approach improves transparency and strengthens the integrity of green finance.

Assessing additionality is both essential and methodologically complex. Again, additionality asks whether an intervention – financial or otherwise – leads to outcomes that would not have occurred without it. This requires constructing a credible counterfactual, which is inherently hypothetical and therefor often contested. Yet, without this step, claims of impact risk being unsubstantiated or misleading.

A robust assessment of additionality begins with a clear theory of change – a structured narrative linking inputs to intended outcomes (Ong, 2023). However, this must be complemented by a theory of behaviour, which considers how actors are expected to respond to interventions. As Gillenwater (2012a) emphasizes, assumptions about rationality, bounded rationality, or altruism are types of behaviour classifications that significantly influence the credibility of additionality claims. These behavioural assumptions are often implicit but must be made explicit and justified to reduce uncertainty and improve transparency.

Additionality can be assessed ex-ante or ex-post (before or after the intervention). Ex-post assessments benefit from observable data and allow for more rigorous causal inference using econometric methods such as difference-in-differences (DiD), randomized control trials (RCTs), or regression discontinuity designs (RDDs) (Winckler et al., 2021). These methods compare treated groups with control groups to isolate the effect of the intervention.

Ex-ante assessments, by contrast, rely on forecasts and assumptions. They are crucial for steering investments toward transformative outcomes, especially in the context of climate transition. However, they face greater uncertainty and require careful construction of baseline scenarios, often using historical data, sectoral benchmarks, and scenario modelling (e.g., Michaelowa et al., 2022).

Several tools and frameworks are used to assess impact, each with strengths and limitations (Winckler et al., 2021):

Each method must grapple with data gaps, modelling complexity, and institutional reluctance to embrace uncertainty. These challenges are particularly acute in green finance, where the pressure for scalability can conflict with the need for rigor.

The lack of standardized methodologies remains a major barrier to credible additionality assessment. However, several initiatives are working to fill this gap. Among those are Impact frontiers, Operating Principles for Impact Management (OPIM) and IRIS+ to only name a few. These frameworks aim to improve comparability, reduce reporting burdens, and enhance the credibility of impact claims by providing standardized metrics and principles.

Quantitative models are precise but difficult to validate. Qualitative assessments provide context and nuance, especially in early-stage or innovative projects (Winckler et al., 2021). A mixed-methods approach is often robust as it combines empirical rigor with contextual insight. Different parameters and methods are adequate for financial and non-financial interventions. The challenge is connecting case-level output with a higher societal outcome (see figure 2). This is also clear when considering the impact dimensions mentioned.

Carter et al. (2018: 4) propose approaching additionality from a probabilistic perspective: Rather than “measuring” additionality, we should “start asking under what circumstances we think additionality is more likely”. Gillenwater (2012a) also discusses this approach in the methodology debate. In cases of impact investing and blended finance, a probabilistic independent variable may be useful. In these cases, a more pragmatic approach is sufficient, as we recognize that some uncertainty is unavoidable, yet still prefer the ‘best possible’ option. However, in the carbon market, it is important to measure the exact impact, as a specific amount of emissions must be attributed to the financed projects.

The absence of credible marginal or additional impact in green finance carries significant risks among those are inefficiency, loss of trust and policy shortcomings. Capital may be allocated to projects that would have found finance anyway, resulting in a suboptimal allocation of scarce financial resources. Without verifiable impact, stakeholders, including investors, regulators, and the public, may lose confidence in green finance instruments. If green finance mechanisms fail to deliver tangible environmental benefits, they risk undermining broader climate policy objectives. This is particularly relevant in the context of the EU’s climate ambitions and the credibility of instruments such as the EU Taxonomy.

This brief emphasizes that transparency is essential for avoiding these risks. Green Finance is often promoted using phrases such as “driving environmental progress,” “catalyzing climate solutions,” “investing in a better future,” and “funding projects that make a difference.” These phrases reflect the widespread expectation that green finance contributes to environmental outcomes. Semantically, “contribution” implies something additive. Without clear reporting on project outcomes and counterfactuals, the legitimacy of additionality claims – and, consequently, the credibility of green finance – is compromised.9 When additionality is properly assessed and demonstrated, it can lead to different opportunities. Financial support can be directed toward projects that truly need it – those that would not survive without external funding. The duration of effective financial support can further be better assessed and targeted. By focusing on interventions that create real change, additionality enhances the environmental and social outcomes of green finance. Therefore, demonstrating additionality can generally enhance trust in green finance instruments and supports their integration into broader regulatory and investment frameworks.

Considering the issues related to the additionality problem, the criterion can be seen as a guiding principle that helps improve the effectiveness of interventions – even when outcomes deviate from initial intentions. Greater transparency, sector-wide benchmarks, and long-term evaluation frameworks could help align incentives by making it clearer which interventions are truly impactful. The idea of a “positive tipping point” (Antonioli, 2024: 5) in green finance – where subsidies are no longer needed – suggests a direction for aligning incentives with long-term transition goals.

We acknowledge a clear lack of standardization in how additionality is defined and measured across frameworks. The inconsistency in opinions around additionality leads to ambiguity. True, stricter standards and methodological rigor can increase bureaucratic burden and transaction costs, possibly discouraging participation. However, without such rigor, the risk of misleading claims increases. This does not necessarily take the form of greenwashing – labelling activities as “green” despite lacking ecological sustainability – but rather what might be called “additionality washing.” when the positive impact of a financial intervention is overstated or falsely implied.

Therefore, we advocate for the pragmatic application of the additionality criterion. Although counterfactuals are hypothetical, they are essential for ensuring transparency and effectively driving transformation with funds. However, the direction of that transformation should be determined by democratic, open debate.

Similarly, Liang and Gao (2022) outline four scenarios that could enable additionality: (1) issuers accepting lower returns for reputational gains, (2) concessional investors accepting lower returns for certified additionality, (3) increased returns through policy or market incentives, and (4) reduced risk via certification.

From a regulatory perspective, the authors propose four ways to improve the effectiveness of climate funding and green finance. First, they recommend classifying green finance products into two categories: “green statistics financial products” (without verified additionality) and “green impact financial products” (with verified additionality). Second, they advocate for mandatory disclosure of whether additionality has been assessed and verified. Third, they call for further research to minimize subsidized windfall profits. Lastly, they recommend updating green finance standards, such as the EU Green Bond Standard, to include mandatory additionality disclosure and greater transparency.

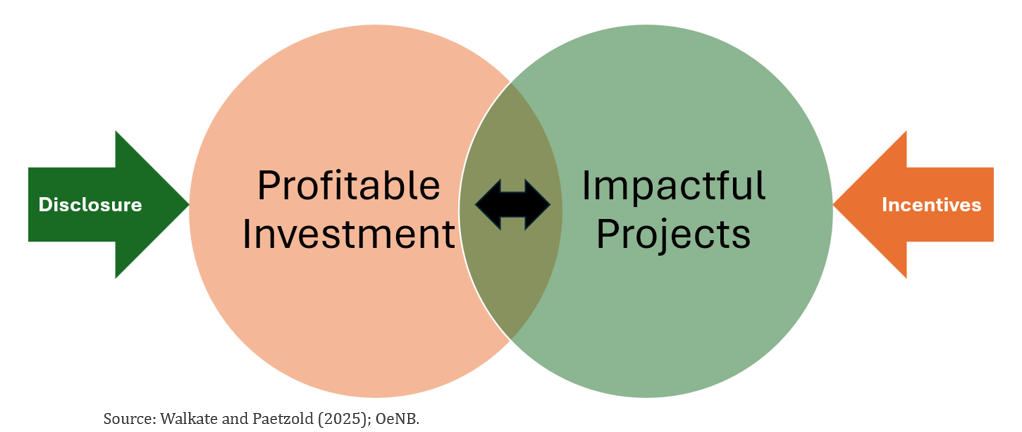

Figure 4. Expanding the space for investible projects with additional impact

People may have different views on these proposals and we recognize their pros and cons. Nevertheless, we believe it is crucial for investors to show how their actions address urgent global issues. In our view, this is the ultimate purpose of green investments. Given the unsustainable nature of current economic affairs, sustainability necessarily entails change. This change must result in a tangible impact beyond a baseline scenario — it must be measurably additional, at least in relative terms. Policies can support this effort in two ways (see Figure 4). First, financial regulators should promote transparency by assessing additionality based on disclosed facts and context. Second, fiscal policy could encourage private investment in the transition to a low-carbon, sustainable economy by increasing returns or decreasing risk.

Amjad, N., C. Andrews, B. Constable-Maxwell (2024). Engagement and Investor Additionality in Impact Investing. M&G Investments. Website: https://www.mandg.com/investments/professional-investor/en-gb/insights/mandg-insights/latest-insights/2024/03/engagement-and-investor-additionality-in-impact-investing

Antonioli, D. (2024). Financing the Transitions the World Needs: Towards a New Paradigm for Carbon Markets. Chapter 2: Rethinking Additionality. Transition Finance. https://tranfin.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Ensuring-Transitions-New-Paradigm-for-Carbon-Chapter-2-Rethinking-Additionality.pdf

Babic M. (2024). Green finance in the global energy transition: Actors, instruments, and politics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2024.103482

Bhatnagar, S., D. Sharma (2022). Evolution of green finance and its enablers: A bibliometric analysis. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112405

Bhutta, U., S., Tariq, A., Farrukh, M., Raza, A., M.K. Iqbal (2022). Green Bonds for Sustainable Development: Review of Literature on Development and Impact of Green Bonds. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 175: 121378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121378

Brest, P., K. Born (2013). Unpacking the Impact in Impact Investing. https://doi:10.48558/7X1Y-MF25

Brown, M. (2025). Viewpoint: The three pathways to impact investing additionality. https://impact-investor.com/viewpoint-the-three-pathways-to-impact-investing-additionality/

Busch, T., P. Bruce-Clark, J. Derwall, R. Eccles, T. Hebb, A. Hoepner, C. Klein, P. Krueger, F. Paetzold, B. Scholtens, O. Weber (2021). Impact investments: a call for (re)orientation. SN Bus Econ 1, 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-020-00033-6

Carr, P., C. O’Shaughnessy, S. Dancer, G. Russel (2008). Additionality Guide. English Partnerships – The National Regeneration Agency 3rd.

Carter, P., N. Van de Sijpe, R. Calel (2018). The Elusive Quest for Additionality. CGD Working Paper 495. Washington DC: Center for Global Development.

Downey, A. (2022). Additionality explained. Blog. https://www.sylvera.com/blog/additionality-carbon-offsets

Du Monceau, T., A. Brohé (2011). Baseline Setting and Additionality Testing within the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). Briefing Paper. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2017-02/additionality_baseline_en_0.pdf

DVFA (2023). DVFA-Leitfaden Impact Investing. DVFA Fachausschuss Impact, Deutsche Vereinigung für Finanzanalyse und Asset Management e. V. https://dvfa.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DVFA-LeifadenImpact2023-10.pdf

EIB (2025). Additionality and Impact Measurement. European Investment Bank. https://www.eib.org/en/projects/cycle/monitoring/aim

Escalante, D., D. Abramskiehn, K. Hallmeyer, J. Brown (2018). Approaches to Assess the Additionality of Climate Investments: Findings from the Evaluation of the Climate Public Private Partnership Programme (CP3). Climate Policy Initiative. CPI Report. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/approaches-to-assess-the-additionality-of-climate-investments-findings-from-the-evaluation-of-the-climate-public-private-partnership-programme-cp3/

European Commission (2024). ESG Rating Activities. Website. https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/esg-rating-activities_en

Findlay, S., M. Moran (2019). Purpose-washing of impact investing funds: motivations, occurrence and prevention. Social Responsibility Journal, Vol. 15 No. 7, pp. 853-873. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-11-2017-0260

Füllgraf, S. (2023). Marktbericht nachhaltiger Geldanlagen 2023. Deutschland und Österreich. FNG. https://www.forum-ng.org/fileadmin/Marktbericht/2023/FNG_Marktbericht2023_Online.pdf.

Gillenwater, M. (2012a). What is Additionality? Part 2: A Framework for More Precise Definitions and Standardized Approaches. Discussion Paper (version 03). Greenhouse Gas Management Institute, Silver Spring, MD, January. https://web.archive.org/web/20140821171316/http:/ghginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/content/GHGMI/AdditionalityPaper_Part-2%28ver3%29FINAL.pdf

Gillenwater, M. (2012b). What is Additionality? Part 1: A long standing problem. Discussion Paper (version 03). Greenhouse Gas Management Institute, Silver Spring, MD, January.

GSIA Alliance (2023). Definitions for Responsible Investment Approaches. https://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/ESG-Terminology-Report_Online.pdf.

IFC (2018). Multilateral Development Banks’ Harmonized Framework for Additionality in Private Sector Operations. International Financial Corporation, World Bank Group. https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2018/201809-mdbs-additionality-framework

ILF Fund (2020). Deep Dive into Impact-Linked Finance. Blog. https://ilf-fund.org/deep-dive-impact-linked-finance/

Impact Europe (2023). Joint Letter: How to Tailor SFDR to Impact. https://www.impacteurope.net/sites/www.evpa.ngo/files/documents/Joint-letter-how-to-tailor-SFDR-to-impact.pdf

Impact Frontiers (2025a). Five Dimensions of Impact. Website. https://impactfrontiers.org/norms/five-dimensions-of-impact/how-much/

Impact Frontiers (2025b). Impact Performance Reporting Norms Version 1. Website: Impact for investment decision-making | Impact Frontiers

IRIS. (2025). IRIS+ System Standards. Catalog of Metrics. The GIIN. Website. https://iris.thegiin.org/metrics/

Küblböck, K., H. Grohs (2020). Blended Finance und das Potenzial für die Entwicklungszusammenarbeit. Österreichische Forschungsstiftung für Internationale Entwicklung – ÖFSE.

Lam P., J. Wurgler (2024). Green bonds: new label, same projects. NBER Working Paper 32960. http://www.nber.org/papers/w32960

Lee, S., S. Jung (2024). Social return on investment as a tool for environmental impact and strategic assessments: Evidence from South Korea. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2024.107765

Liang, X., H. Gao (2022). Assessing the Quality of Green Finance Standards. In: Cerniglia, F. and F. Saraceno (eds.). Greening Europe. Greening Europe: 2022 European Public Investment Outlook. Cambridge, UK: Open book Publishers. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0328

McFarland, B. J. (2024). Carbon Reduction Projects and the Concept of Additionality. In: Sustainable Development Law & Policy 11(2). 15–18. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1463&context=sdlp

OeEB (2021). Prinzip der Additionalität. In: Die OeEB im Überblick. Oesterreichische Eintwicklungsbank. https://www.oe-eb.at/ueber-die-oeeb/die-oeeb-im-ueberblick.html

Ong, J. (2023). Additionality: What it is and how we approach it. Blog. https://insights.amasia.vc/p/additionality-what-it-is-and-how

Perspectives (2023). Tool for the Demonstration and Assessment of Additionality. TOOL01, final tool. International Initiative for Development of Article 6 Methodology Tools. https://perspectives.cc/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/TOOL01_17.03.2023.pdf

Salakhova, D. (2023). Beyond the Greenium: Assessing the Additionality of Green Bonds. ECGI Blog. https://www.ecgi.global/publications/blog/beyond-the-greenium-assessing-the-additionality-of-green-bonds?trk=publicpostcomment-text

Salzman, J., D. Weisbach (2024). The Additionality Double Standard. University of Chicago Coase-Sandor Institute for Law & Economics Research Paper No. 1023. https://ssrn.com/abstract=5014588

Senn, M. (2025). EU Secretly Shields Banks from Accountability—Here’s How. Social Europe Blog, March 31. https://www.socialeurope.eu/eu-secretly-shields-banks-from-accountability-heres-how?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Simsa, R. (2014). Methodological Guideline for Impact Assessment. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284680587_Methodological_Guideline_For_Impact_Assessment

Verra (2025). Verified Carbon Standard. How it works. Website. https://verra.org/programs/verified-carbon-standard/#how-it-works

Walkate, H., F. Paetzold (2025). Impact investing grows up: from intentionality to additionality. Illuminem. Available at: https://illuminem.com/illuminemvoices/impact-investing-grows-up-from-intentionality-to-additionality-part-15

Winckler. A., O. H. Hansen, J. Rand (2021). Evaluating financial and development additionality in blended finance operations. OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers No. 91. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/a13bf17d-en.

Green Finance aims to mobilize and direct (particularly private) capital to address climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation. Specifically, it helps adapt to risks and mitigate risks, while actively contributing to the transition to a greener and more sustainable economy.

Apart from ESG integration, which primarily aims to mitigate financial sustainability risks, various positive, impact-oriented strategies exist in green finance. These strategies are: (1) excluding clearly unsustainable assets; (2) investing in relatively green assets (i.e., best-in-class); (3) impact investing in explicit sustainable projects; and (4) engaging with the management of owned firms to adopt green business models. However, the effectiveness of these strategies could be offset by investors who are indifferent to environmental concerns.

Research and pilot projects may have no measurable environmental impact yet are crucial as they pave the way for future improvements. This is why assessments should be sensitive to context and recognise the importance of these projects in terms of indirect additionality.

Blended finance uses public or philanthropic funds to attract private investment in projects that would not otherwise be funded due to high risk or low return, but which have social or environmental benefits.

The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) requires financial firms to disclose how they integrate sustainability risks and impacts into investment decisions. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) mandates companies to report detailed information on environmental, social, and governance metrics. The EU Green Taxonomy provides a classification system defining which economic activities are environmentally sustainable.

This quote reflects the two time dimensions of ex-ante and ex-post assessments.

When it comes to climate adaptation finance, the concept of additionality should not be taken literally. There, the objective is to minimise harm and damage.

This is akin to the inside-out perspective of double materiality adopted in various EU disclosure regulations for sustainability assessments. Unlike financial materiality, which takes an outside-in approach, impact materiality refers to the risks and opportunities posed by a company and its business partners to the environment and society.

Green finance is typically understood through two complementary lenses: a risk-oriented perspective and an impact-oriented perspective (see: double materiality). Arguably, even the risk perspective ultimately aims to contribute to a more sustainable world. If it did not, it might more accurately be described as “brown de-risking finance” or the like. Of course, the real-world sustainability impact of disclosing and managing climate- and nature-related financial risks is abstract, and its additionality is nearly impossible to measure. Nevertheless, the impact should exist, and it should be additional, at least in relative terms.