Chinese economy will overcome the US before the end of the next decade. This catching-up process and its global consequences have raised much concern recently. China became a ‘strategic adversary’ for the USA, the EU’s reaction has been rather hesitant. This Note discusses some aspects of a new emerging global order, arguing that rather than turning to protectionism the rising Chinese FDI should be considered as an opportunity. EU policies with respect to China should be pro-active and shaped by recognising this tendency as a ‘new normal’.

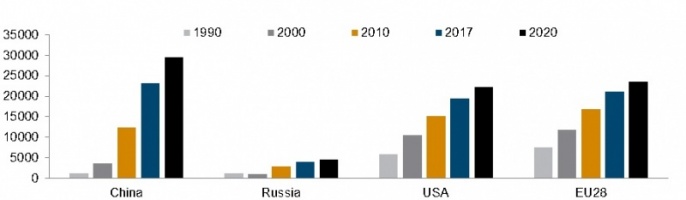

The Chinese economy is poised to overcome the US before the end of the next decade (in real PPP terms it is already now 20% bigger according to the World Bank). The latest IMF forecast (World Economic Outlook, April 2019) expects that China’s current economic lead over the USA and the EU is going to increase by another 10 percentage points by 2020 (Figure 1). The four decades long of China’s unprecedented catching-up process and its geopolitical consequences took most observers in the West unprepared. In this context, the recent (January/February 2019) issue of the influential US journal Foreign Affairs was dedicated to the implicit question “Who Will Run the World?”. While the Chinese-led world order would be an ‘illiberal one’, a ‘new democratic rules-based’ order is less likely than a world with ‘little order according to the opinion expressed by Richard Haas (p. 30). And at least in the Indo-Pacific region, China is ‘trying to displace, rather than replace’ the United States (ibid, p. 31). Since the publication of these “Who Will Run the World” essays, the frequency of China-focused articles and policy analyses has exploded on both sides of the Atlantic.

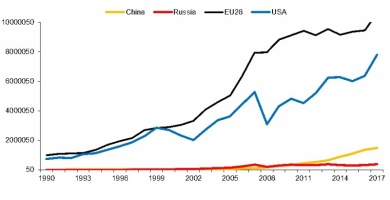

Figure 1: GDP of global economic powers, at PPP, USD billion, 1990-2020

Source: The World Bank (WDI); IMF (April 2019); own estimates

The Chinese use of projecting newly gained economic power has become obvious at the latest with the ‘One Belt One Road’ (OBOR) initiative launched in 2013. This huge, long-term and wide ranging infrastructure investment project is intended to spread Chinese influence beyond Eurasia to Africa and especially to Europe by offering credits without any ‘usual Western strings attached’. The rise of China’s economic power has provoked contradictory reactions in the West. In the USA, President Trump cancelled the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal negotiated by the Obama administration (which excluded China anyway), launched the trade war by imposing tariffs on imports from China and, more recently, imposed restrictions on Chinese investments, bans and warnings on Chinese digital equipment purchases and technology transfer (even issuing an arrest order on Huawei Chief Financial Manager Ms. Meng Wanzhou in Canada), accusing China of intellectual property theft and spying, etc. In short, China became a ‘strategic adversary’ for the USA, with some high-level officials in the Trump administration seeing China as an ‘existential threat’.

The European Union does not speak with one voice (as usual), but has joined the US blame and shame campaign on China in December 2018, with both Germany (where Huawei European headquarters is located), France and the United Kingdom raising concerns about Chinese advanced digital technology, in particular bidding for advanced 5G telecom licences. According to Bloomberg, the Chinese wireless technology is winning in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, reaching a 40% market share in 2018, followed by Ericsson with 36%. In the Czech Republic, local cybersecurity experts even call for a boycott of Chinese electronic equipment on the absurd pretext that ‘all Chinese producers are state-controlled’. The Czech National Cyber and Security Information Agency issued a similar warning against using Huawei and ZTE telecom equipment by government agencies, leading to a (un)diplomatic spat between the Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babis and the Chinese Ambassador Zhang Jianmin at the end of December in Prague. In what seems to be a concerted Chinese-bashing effort, the Polish police detained the local Huawei representative on spying allegations in January 2019. Recently, both Germany and the United Kingdom cleared Huawei from the bidding ban on 5G technology – despite bitter US complains – provided the company gives the necessary security guarantees. (A more balanced position on Huawei’s alleged threats and vulnerabilities was provided by The Economist at the end of April 2019 where geopolitical aspects of the company and rising Chinese economy were highlighted.)

Ironically, the above Czech-Chinese dispute adds more fuel to the EU-China rivalry and is of particular importance since the ‘16+1 Framework and Economic Relations between China and the Central and Eastern European Countries’. Established already in 2012, ‘16+1’ represents the so far most important Chinese investment initiative in Europe, with pledged Chinese investment in Europe, mostly to non-EU states, reaching USD 15.4 billion according to the Financial Times (FT, 12 April 2019, p. 5). The ‘16+1’ initiative has been actively promoted by Prague and the Czech President Milos Zeman who attended the OBOR/BRI Summit in Beijing at the end of April 2019, in particular. Similar to the ‘16+1’ initiative, the EU’s reaction to OBOR has so far been delayed and rather hesitant: only in September 2018, the European Commission adopted its ‘EU Strategy on Connecting Europe and Asia’ that aims to link Europe with Asia and offers a different approach to that taken by Beijing with its flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The EU approach is based on sustainable and comprehensive connectivity, based on international rules-based connectivity. However, compared to the Chinese BRI initiative, the proposed EU Connectivity Strategy does not only lack sufficient resources, but is probably also excessively restrictive and thus less attractive – despite numerous recent criticism of Chinese BRI-related activities in Africa and Asia that may lead to a ‘debt trap’ (disappointments with the Chinese financing and long-term lease of the Sri Lanka’s port Hambatota, or the highway construction in Montenegro are among frequently quoted recent examples).

The above reactions to rising Chinese economic power and its display on the economic arena witness the Western discomfort with a new emerging global order. In recent months, hardly any day in mainstream western media (Financial Times, The Economist, New York Times, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Der Spiegel, Die Welt, etc) passes without discussing, mostly critically, the alleged geopolitical and economic threats arising from Chinese economic expansion. The latest prominent coverage of China-related issues was related to the BRI Summit in Beijing at the end of April 2019 that was attended by more than 30 heads of state, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, Italian Prime Minister G. Conte, Indian Prime Minister N. Modi among others, while no high level US official chose to participate as Washington sticks to its adverse position towards China. (In contrast, Russia is changing the pivot from Europe to China as one of the consequence of conflict with the West).

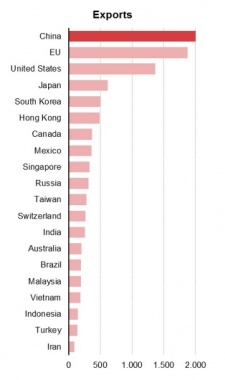

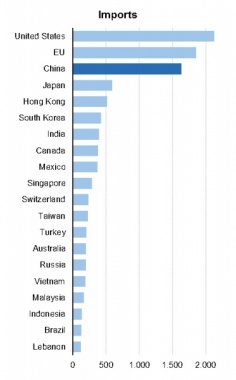

Figure 2: Top 20 exporters and importers of goods in the world, 2017, EUR billion

|

|

Source: adopted from Eurostat (online data code: ext_lt_introle)

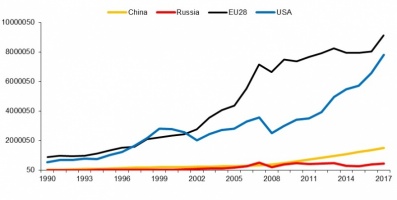

Indeed, the rising Chinese foreign investment abroad is a relatively new phenomenon (contrary to China’s swelling merchandise trade surpluses – see Figure 2). Except for Germany, Finland and Ireland, all EU member states recorded trade deficits with China (more than EUR 180 billion in 2018 for EU-28). According to UNCTAD, Chinese outward were meagre (less than USD 20 billion per year on average) ten years ago, but jumped ten times (to nearly USD 200 billion) in 2016. Chinese outward FDI stocks reached USD 1500 billion by end-2017, almost matching the cumulated inward FDI (in 1995 the inward FDI stocks in China – USD 100 billion – were more than five times bigger than outward FDI –see Figures 3 and 4). This rapid growth notwithstanding, Chinese FDI are still rather low in relative terms: as of end-2017, both inward and outward FDI stocks accounted to 12% of Chinese GDP (compared to some 40% in the USA, more than 50% in the EU and nearly 30% in Russia). Also in Central and Eastern Europe, Chinese investments are still rather low – the highly promoted ‘16+1’ initiative notwithstanding: the Chinese FDI stock in CESEE reached so far only 0.2% of the total FDI invested in the region according to wiiw estimate.

Summarising, one can conclude that with a growing economy and trade, and with its ongoing technological upgrading, the Chinese investment abroad is also poised to grow in future – in line with the rising global strength of China – of course unless there is a major disruption in trade flows and the resulting global crisis. At the April 2019 BRI Summit, trade deals valuing more than USD 60 billion were reportedly signed whereas BRI-related investment reached about USD 100 billion already by the end of 2018. Attempts to restrict Chinese investments seem to be either a poorly disguised attempt to contain the rise of China or a part of an emerging global trend towards protectionism. Paraphrasing the famous paper on competitiveness by Paul Krugman, these efforts are not only wrong, but could represent a ‘dangerous obsession’ as well. As far as the EU is concerned, the rising Chinese FDI should be considered as an opportunity rather than threat, and the EU policies with respect to China should be shaped by recognising this tendency as a ‘new normal’. Similar conclusions with respect to a ‘more realistic’ EU approach towards China have been drawn in the recent Policy Insights paper by the CEPS.

Figure 3: FDI inward stock, by region and economy, 1990-2017 (USD million)

Source: UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2018

Figure 4: FDI outward stock, by region and economy, 1990-2017 (USD million)

Source: UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2018