Like many of you, I have long been interested in the potential for innovation to improve financial services. One of the most notable developments in recent years has been the entry of large technology companies into the financial services arena, offering payment services, credit, insurance and even wealth management to retail and small business clients.

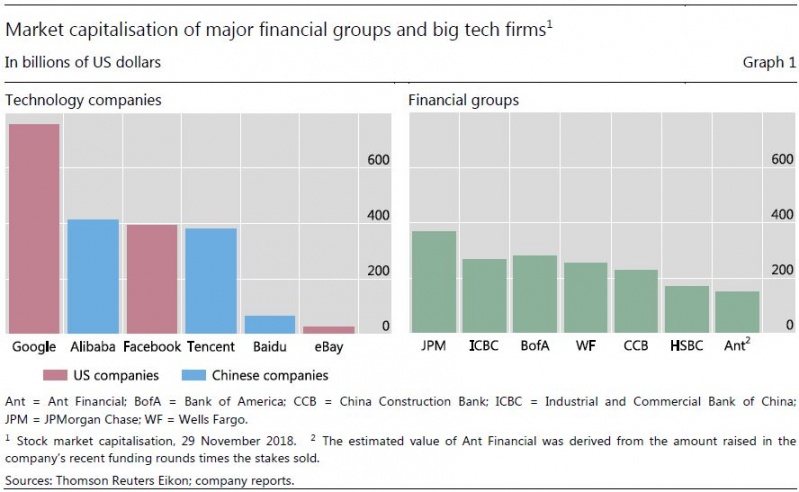

These big tech firms are most active in China, particularly Alibaba Group’s Ant Financial and Tencent, but they are also present in East Africa, South and Southeast Asia, Europe, Latin America and North America.2 As Graph 1 shows, “big tech” is an apt name. The market capitalisation of large technology companies is in some cases bigger than the world’s largest financial institutions.

Big tech firms have special characteristics that distinguish them from fintech firms. While fintech firms offer financial services with digital technology, big tech firms approach from the other direction: their primary business is technology and not finance.

In particular, big tech firms’ main advantage is that they can exploit existing customer networks and the massive quantities of data generated by their business lines. Big data is at the core of their business. Data give big tech firms the edge over competitors. But to public policymakers, this aspect represents one of the greatest challenges.

Big tech’s involvement in finance started with payments, especially in China, where tech solutions for mobile payments have really taken off: big tech mobile payments for consumption represent 16% of GDP in China, compared with less than 1% in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, where credit cards are more popular.

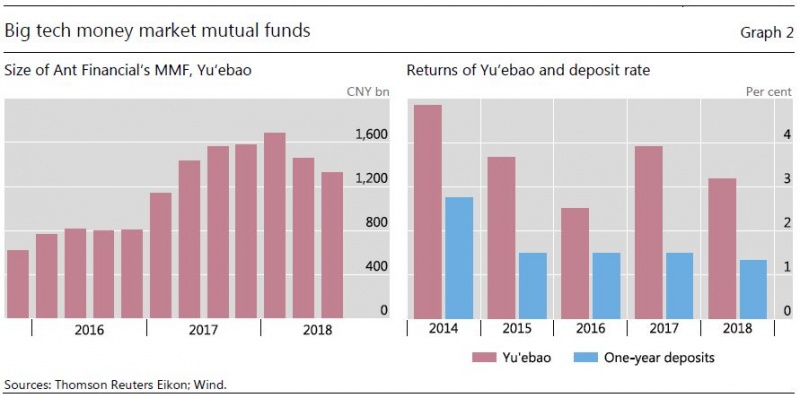

Big tech firms also extend credit, or sell insurance and savings products, either directly or in partnership with financial institutions. Online money market funds (MMFs) have also grown significantly in recent years. For instance, as the left-hand panel of Graph 2 shows, the Yu’ebao (or “leftover treasure”) fund, offered by Ant Financial, had assets under management of CNY 1.3 trillion (USD 200 billion) in September 2018, making it the largest MMF in the world. Its return is higher than that on a one-year term deposit (Graph 2, right-hand panel).

The implications for public policy are foremost in my mind, and here the growth of big tech raises a host of questions:

I warn you now that I won’t be able to give final answers to these questions today. But I will come back to them at the end. I will start by considering the trends and potential drivers of big tech activities in financial services around the world. Then I shall enter more speculative territory, analysing the possible effects of big tech on financial intermediation and the new conceptual and practical challenges that big tech poses for public policy.

Although big tech and fin tech firms come at financial services from different directions, their growth rests on the same drivers. Demand is one factor: unmet customer needs, consumer preferences, ease of access for the iPhone generation. Supply is another: access to multiple sources of data, technological advances, lack of regulation, concentration and lack of competition.

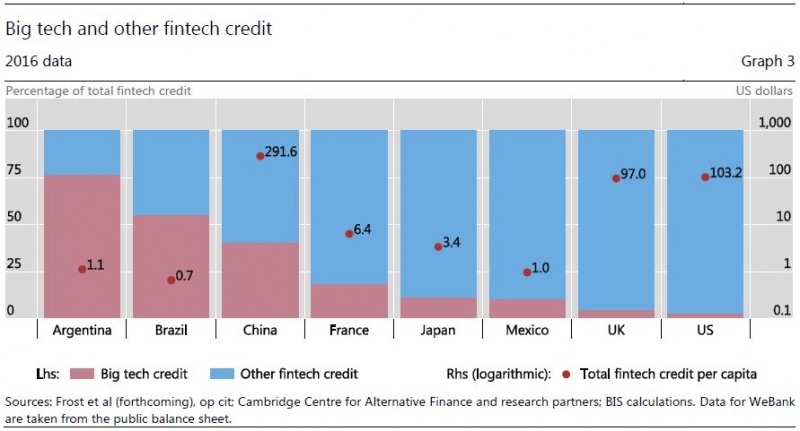

The development of fintech credit, which includes big tech credit, varies greatly across economies. The red dots in Graph 3 show that fintech credit per capita is higher in China, the United Kingdom and the United States. However, the share of big tech credit in total fintech credit, represented by the red shading on the bars, is highest in Argentina and Brazil. These countries have very small fintech credit markets.

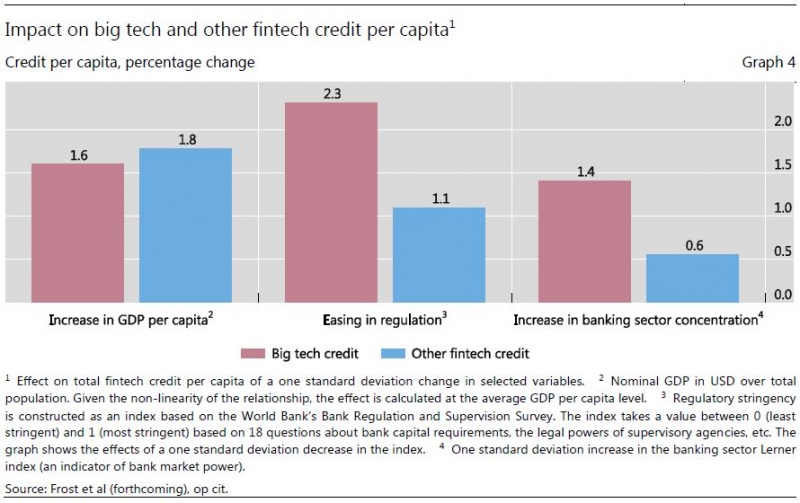

Recent BIS analysis,3 summarised in Graph 4, shows that these differences in development reflect differences in economic growth, the strength of financial regulation and the amount of competition in the banking sector. Interestingly, big tech credit sees more of a boost from easier financial regulation and increased banking sector concentration than fintech credit.

However, macroeconomic and institutional drivers are only part of the story. To better understand the competitive and comparative advantages of big tech, let me detail some characteristics of their business model.

In contrast to banks, big tech firms do not have a traditional branch network through which to interact with customers. Instead, big tech lenders build a picture of their customers using proprietary data from their online platforms and from other sources, such as social media and customers’ digital footprints.4 Notably, decisions on whether or not to lend are based on predictive algorithms and machine learning techniques.

This gives big tech lenders a method of client scoring that in itself could give them an advantage over traditional banks, which commonly rely more on human judgment to approve or reject credit applications. Moreover, this could also be applied to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that cannot provide audited financial statements.5

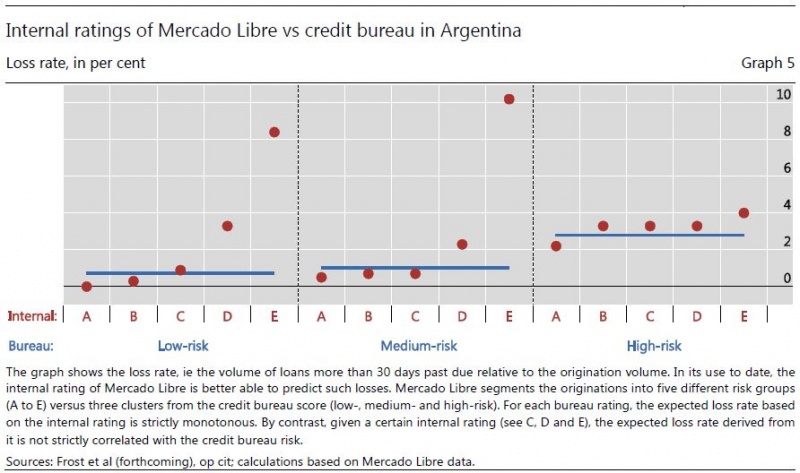

Preliminary evidence suggests that leveraging transactional data with artificial intelligence and machine learning could help predict repayment prospects. For instance, Graph 5 shows that the credit model of Mercado Libre in Argentina has, in the short run at least, outperformed the local credit bureau in predicting losses of corporate borrowers.6

However, there are possible side effects from this new financial intermediation process. First, big tech lending technology does not involve human intervention or a long-term relationship with the client. These loans are strictly transactional, typically short-term credit lines that can be automatically cut if a firm’s condition deteriorates. This means that, in a downturn, there could be a large drop in credit to SMEs and large social costs.7 A complete evaluation of this new form of financial intermediation requires a complete business and financial cycle.

A second point relates to the business model of big tech lenders, which is different from that of traditional banks, at least for small business loans. A traditional commercial bank collects small deposits and then channels the proceeds into large loans. But many big tech firms first extend the loan, and then raise the money to fund it. Funding models differ across firms, with some relying on a mix of internal sources and syndicated loans, and others relying mainly on repackaging and onselling the loans to third party investors.

We thus face new originate-to-distribute models with characteristics that need to be fully explored. What are the information gaps between the big tech lender and the investor? How much skin in the game do big tech firms keep? Could this new originate-to-distribute model create incentive problems and financial instability?

A third point relates to the role that big tech firms’ dominance in payment systems allows them in the broader financial system. For example, in China, the size of some Chinese MMFs may pose potential systemic financial risks. These funds extend longer-term, risky credit that is funded by sources that can be redeemed on demand at par, and used for payments.8 This could give rise to credit and liquidity risks.

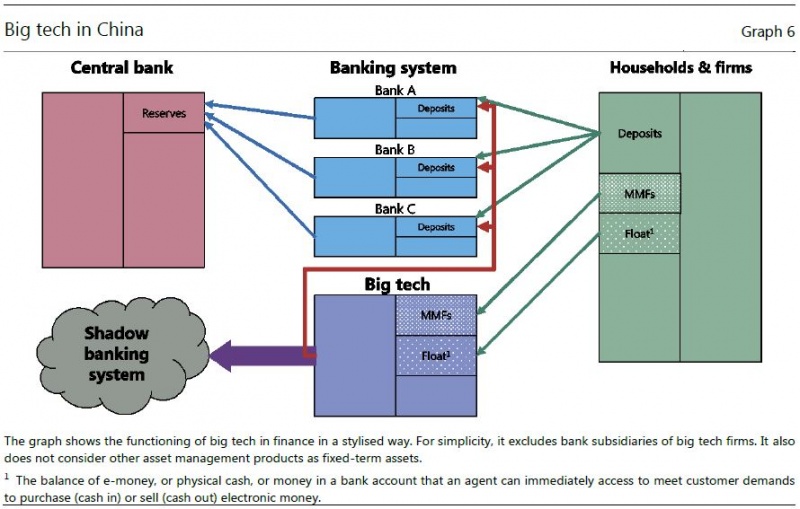

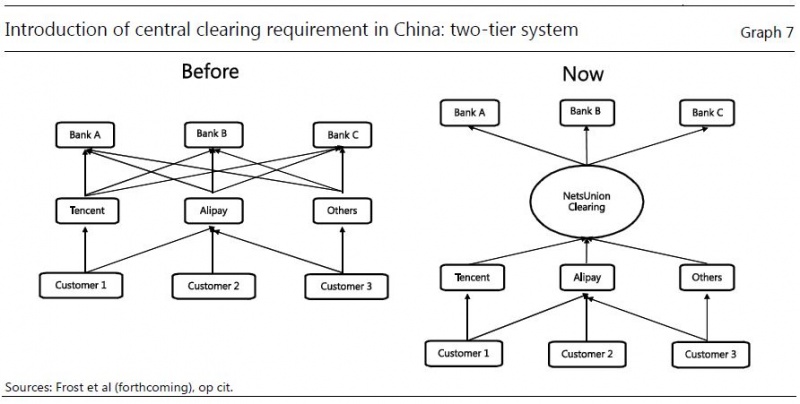

Customers of big tech payment services also maintain sizeable balances with big tech companies in order to use their payment services, the so-called custodial accounts or “float”. As shown in the stylised representation of Graph 6, the float represents a large and captive funding source for big techs, which pay no interest in return.9 Big techs have been known to deposit these funds in bank current accounts and earn interest (see the red lines in the graph). As can be seen in the left-hand panel of Graph 7, big tech entities often used to hold funds simultaneously at multiple banks. This creates complicated and opaque bilateral relationships between third-party payment platforms and banks.10

For these reasons, the authorities in China have recently adopted new rules. Let me turn to this and other implications for public policy.

In order to understand how public policy should adapt to these changes in financial intermediation, we need to understand the social costs and benefits big tech activities bring.

A first challenge is the possible financial stability risks. In particular, as discussed above, large MMFs may pose systemic risks, as they could be subject to investor runs in the event of credit or duration losses.11

Moreover, if big tech platforms deposit customer funds directly with banks, they create a parallel payments system that is not properly overseen by the central bank. This could potentially undermine financial stability and shield payments from the scrutiny of authorities guarding against illegal activities, such as money laundering.12

Public authorities have these risks on their radar and have taken steps to address them. For example, the People’s Bank of China (PBC) and the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) have introduced a cap on instant redemptions on MMFs. At the same time, they have increased disclosure obligations to avoid misleading forms of advertising.13

The PBC has also recently adopted reforms for big tech firms in payments, dealing with reserve requirements and central clearing requirements.

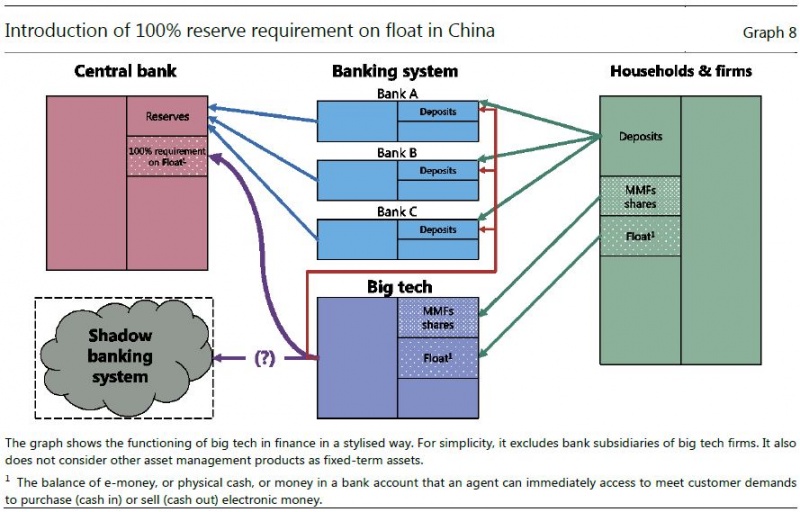

First, from January 2019, the PBC will require big tech firms to keep a 100% reserve requirement on the custodial accounts.14 As described in Graph 8, in this way the float is segregated in a specific reserve at the PBC. This is unusual because big tech firms are not banks. The effects of this change are similar to being in a narrow banking system, as it reduces big tech firms’ ability to supply platform credit.

Second, since June 2018, big tech firms have had to channel payments through an authorised clearing house. As can be seen from the right-hand panel of Graph 7, the establishment of a two-tier clearing system improves transparency in the Chinese payment system. This allows the PBC to monitor customer funds on third-party payment platforms.15

A second challenge has to do with traditional welfare issues arising from anti-competitive forces.16

It is too early to judge the overall welfare impact of big tech on competition. If the entry of big tech companies is driven primarily by efficiency gains over incumbent banks and insurers, or by access to better information and screening technology, then big tech makes the financial sector more efficient and aids financial inclusion. This may entice incumbent financial institutions to adopt similar technologies, and the financial system could become more diverse and efficient. But if big tech entry is driven primarily by market power, relying on exploiting regulatory loopholes and the bandwagon effects of network externalities, this could encourage banks into new forms of risk-taking.17 The public policy solution would be to close the regulatory loopholes.

A third challenge is that big tech developments raise issues that go beyond the scope of prudential supervision. Other public policy objectives may also be at stake, such as safeguarding data privacy, consumer protection and cyber-security.

Data privacy and consumer protection do not simply imply cracking down on breaches and educating consumers about how their data are used. They also include avoiding discrimination in credit scoring, credit provision and insurance. Even if sensitive characteristics such as race, religion and gender are not included in the database, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms may fill in the blanks – for example, based on geography or other factors.18

Cyber-threats also challenge global regulators. A big tech firm that provides third-party services to many financial institutions – whether data storage, transmission or analytics – could pose a systemic risk if there is an operational failure or a cyber-attack. What risks could a disruption at a big tech firm managing client data pose to financial institutions? Would the risk be contained, or would the potential for broader amplification require a more coordinated response?

Let me conclude, returning to the questions I posed at the start.

The rapid growth of big tech has undoubted upsides, but these must be balanced against the potential downsides. Big tech firms may improve competition and financial inclusion, put welcome pressure on incumbent financial institutions to innovate, and boost the overall efficiency of financial services. However, such firms may increase market concentration and give rise to new risks, including systemic risks due to the way they interact with the broader financial system. It is therefore important to understand how big tech firms fit within the current regulatory framework, and how regulation should be organised.

Regulators have to provide a secure and level playing field for all participants, incumbents and new entrants alike. At the same time, they have to foster innovative and competitive financial markets. Firms providing similar services or taking similar risks cannot operate under different regulatory regimes. This would create regulatory gaps, with new business models shifting critical activities outside current regulation. At the same time, new challenges are emerging. Some of these lie beyond the traditional remit of financial regulation – for example, the collection and sharing of client data.19 Still, these trends may have profound implications for the evolution of traditional models of financial intermediation and competition among players.

Authorities around the world have a joint interest in an open and frank discussion of public policy goals and responses. We must work together both to harness the promise of big tech and to manage its risks. Global safety and soundness will benefit from more cooperation between supervisors and more information-sharing, especially as big tech firms operate across national borders. As in most financial regulation, international coordination is the name of the game.

As the Chinese nursery rhyme says: “It is easy to break one stick, but far more difficult to break a bunch of sticks in one go.” Cooperation gives strength.

Keynote address by Agustín Carstens, General Manage, Bank for International Settlements, at the FT Banking Summit in London, on 4 December 2018.

Less visibly, but no less importantly, big tech companies are also becoming active in financial services in East Africa and South Asia, through the entry into payment- and banking-related services of Vodafone M-Pesa; in Latin America, with the growing financial activities of e-commerce platform Mercado Libre; in Asia, with the activities of Samsung (Kakao and Samsung Pay) in Korea and of Line and NTT Docomo in Japan, and the payments services of ride-hailing apps Go-Jek operating mainly in Indonesia and Grab operating primarily in Malaysia and Singapore; in Europe, with the banking services offered by Orange; and in the United States, with the budding financial service offerings of Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft. See D Zetzsche, R Buckley, D Arner and J Barberis, “From FinTech to TechFin: the regulatory challenges of data-driven finance”, New York University Journal of Law and Business, 2017; and J Frost, L Gambacorta, Y Huang and H S Shin, “Big tech and the changing structure of financial intermediation”, BIS Working Paper, forthcoming.

See S Claessens, J Frost, G Turner and F Zhu, “Fintech credit markets around the world: size, drivers and policy issues”, BIS Quarterly Review, September 2018; and Frost et al (forthcoming), op cit.

See T Berg, V Burg, A Gombović and M Puri, “On the rise of fintechs – credit scoring using digital footprints”, NBER Working Papers, no 24551, April 2018.

Fintech credit in China, India and Latin America is typically provided to SMEs that do not meet the minimum requirements for completing a bank loan application. Big tech firms are able to overcome these limitations by exploiting the information provided by their core business, such as e-commerce or social media, thus reducing the need for additional documentation from merchants. Moreover, the use of machine learning enables a direct and fast assessment of credit risk that could improve the underwriting process by increasing its speed and also preventing, in some cases, human bias from entering the decision. See Frost et al (forthcoming), op cit; and H Hau, Y Huang, H Shan and Z Sheng, “Fintech credit, financial inclusion and entrepreneurial growth”, University of Geneva, mimeo, 2018.

See Frost et al (forthcoming), op cit. There is also some evidence that the provision of credit by big tech firms in China helps firms to expand their sales, product variety and scale. See Hau et al (2018), op cit; and Y Huang, C Lin, Z Sheng and L Wei, “FinTech credit and service quality”, University of Geneva, mimeo, 2018.

Indeed, the literature suggests that those financial systems based on relationship banking can better protect firms in adversity, especially if banks have sufficient levels of capital. See M Bech, L Gambacorta and E Kharroubi, “Monetary policy in a downturn: are financial crisis special?”, International Finance, vol 17, no 1, 2014, pp 99-119; and P Bolton, X Freixas, L Gambacorta and P Mistrulli, “Relationship and transaction lending in a crisis”, The Review of Financial Studies, vol 29, 2016, pp 2643–76.

On the liability side, MMFs accept money on accounts that are repayable on demand or at short notice and at par. On the asset side, the fund sale institutions invest in structured deposits, negotiated certificates of deposit, corporate bonds, repos and other credit assets.

The reserve funds represent funding available to payment companies for the three- to seven-day clearing period. The value of reserve funds was around CNY 1,000 billion (USD 150 billion) at the end of October 2018.

In this one-tier system, the big tech firms can bypass the traditional two-tier banking system where commercial banks make payments on behalf of clients, but the central bank is the bank to the commercial banks. Big tech firms, for their part, can use the captive funding to lend to smaller banks that are short of funding, or lend through the shadow banking system.

As seen in the Great Financial Crisis of 2007–09, MMFs were like banks without capital and therefore subject to investor runs. The large dimension of MMFs could thus amplify the effects of deleveraging and fire sales. In response to the runs on US MMFs after Lehman’s default, the most run-prone (ie “institutional”) MMFs in the United States must either offer a floating net asset value or invest only in government securities or in repos backed by them. See Financial Stability Board, Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report, March 2018.

The decentralised deposit by big tech firms of clients’ reserve funds in different banks is not conducive to proper and centralised liquidity management. This reduces the possibility of meeting customers’ payment requests in a timely manner and could cause liquidity risks.

See PBC-CSRC, “Guiding opinions on further regulating the services relating to the internet sales and redemption of money market funds”, June 2018. See http://www.csrc.gov.cn/pub/zjhpublic/zjh/201806/t20180601_339014.htm.

This regulatory change is part of a process started in January 2017, when the PBC announced that it was requiring third-party payment groups to keep 20% of customer deposits in a single, dedicated custodial account at a commercial bank and specified that this account would pay no interest. In April 2018, the ratio was increased to 50%. The increase of reserves to 100% is effective from January 2019. Payment firms will earn zero interest on customer funds. See http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-06/05/content_5296169.htm.

Payment information is now centrally stored in a clearing house (the new state-owned clearing house NetsUnion Clearing or one of the other authorised clearing houses), while customer funds are deposited with the central bank or a commercial bank meeting the requirement.

Big tech platforms operate in two-sided markets, deriving revenues by facilitating transactions between two groups of agents. The economics of two-sided markets can give rise to complex interaction between consumers and sellers on a platform. For example, big tech firms could exploit network externalities, resulting in the creation of seemingly impenetrable barriers to market entry even for innovative companies. Yet consumers also accrue benefits when platform operators use upstream revenues to subsidise downstream services. See M Rysman, “The economics of two-sided markets”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol 23, no 3, 2009, pp 125–43.

See G Barba Navaretti, G Calzolari and A Pozzolo, “FinTech and banking. Friends or foes?”, European Economy, no 2, 2017.

There is ongoing debate on how to address and mitigate these biases and a more general discussion on AI ethics. See Financial Stability Board, “Artificial intelligence and machine learning in financial services: market developments and financial stability implications”, Annex B, November 2017.

One example of the intersection between data and finance is the new European Union Payment Services Directive, which entered into force this year and introduced “open banking”. This means that bank account holders can ask their banks to transmit their financial data to third parties. They can also authorise third-party providers to initiate payments from their bank account. Similar initiatives have been taken by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Australia is also set to adopt open banking. Others may follow suit.