For over a decade, zombie firms have been an important topic both in policy and academic discussions. Coined in the seminal paper by Caballero et al. (2008), the zombie term was first used for firms in the stagnating Japanese economy of the 1990s. Zombie firms are corporates that still operate, even though they are no longer profitable. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, this discussion has been reinvigorated. Critics raised the concern that expansive monetary and fiscal policies not only support healthy firms facing liquidity constraints, but also allow zombie firms to avoid bankruptcy. Zombie firms are a relevant policy issue for several reasons. Their existence may raise concerns for the financial stability of the banking system. Should a large number of zombies fail, for instance because vital fiscal support measures are being phased out, or because interest rates rise, this could endanger their creditors. Zombie firms can also withhold resources (capital, workers etc.) from healthy firms that may use them more efficiently. As a consequence, zombie firms can adversely impact healthy firms through spillover effects.

A large part of the zombie literature investigates these spillover effects. Most studies focus on “real” spillovers from zombies to healthy firms in terms of employment, investment, productivity, and profit margins (Acharya et al., 2019, 2022; Banerjee and Hofmann, 2018, 2022; Blattner et al., 2023; Caballero et al., 2008; McGowan et al., 2018; Schivardi et al., 2022). However, only a handful of studies examine “financial” spillovers, i.e. the idea that the existence of zombie firms deteriorates credit conditions and access to capital for healthy firms, so that Andrews and Petroulakis (2019) call financial spillovers an “understudied channel” (p. 3). Those who do investigate this channel indeed confirm negative externalities (see Albuquerque and Roshan (2023) and Acharya et al. (2019) for interest rates, and Andrews and Petroulakis (2019), Chari et al. (2021), Wang and Zhu (2021) and Yu et al. (2021) for credit or lending proxies).

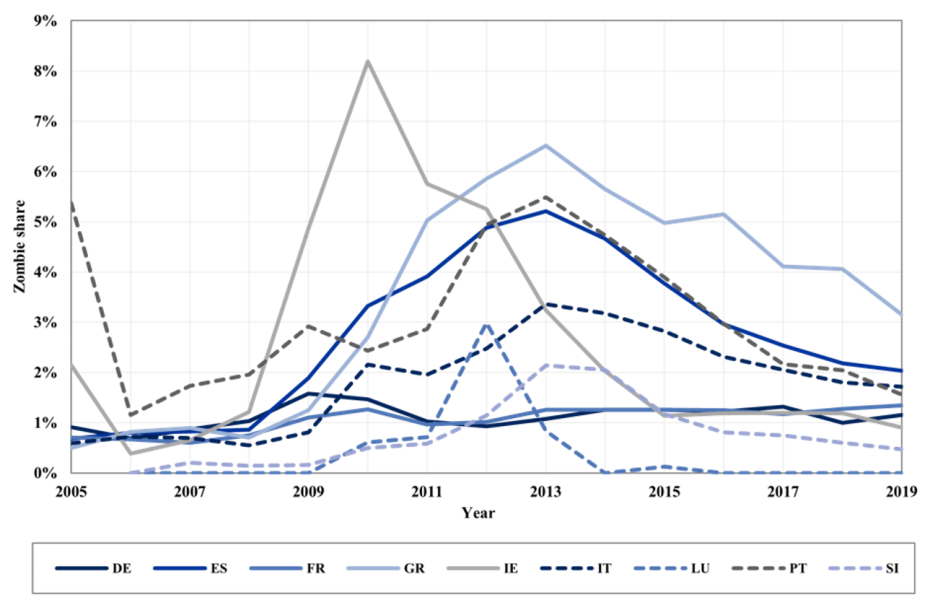

To explore the evolution of zombie firms in the EA, also against established findings in the literature, we first look at firm balance sheet data for the 19 EA countries from 2005-2019; see a selection in Figure 1. We compute asset-weighted zombie shares on the country and sector level, using the zombie definition of Storz et al., 2017.1 For all countries except Portugal, the prevalence of zombie firms was small before the global financial crisis hit in 2008, with shares below 2%. The graph illustrates the course of the crisis, with Greece and Ireland impacted early and hard, whilst other countries were more adversely affected only by the subsequent European sovereign debt crisis (Godby and Anderson, 2016). The so-called “GIIPS countries” (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain) that suffered disproportionately from these two crises exhibit higher zombie shares than the remaining countries. For example, short after the height of the European debt crisis in 2013, the EA average zombie share was 2.2%, whilst the GIIPS countries’ average was 4.7%. These findings are in line with existing literature (for instance Acharya et al., 2019; Pelosi et al., 2021; Storz et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Asset-weighted zombie shares for selected euro area countries, 2005-2019

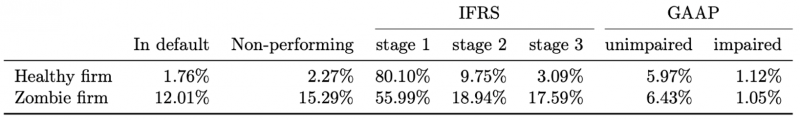

Zombie firms also perform much worse in terms of credit quality indicators, see Table 1. For example, zombie firms are more often declared to be in default and have a higher proportion of non-performing loans (15.29%) than healthy firms (2.27%). Similarly, a much lower proportion of zombie loans is classified as IFRS stage 1, meaning that the credit risk of the loan has not significantly increased since initial recognition. Instead, 18.94% of zombie loans are classified as stage 2 (significant increase of credit risk) and 17.59% as stage 3 (credit risk increased so much as to be considered credit-impaired); in contrast to 9.75% and 3.09% for healthy firms, respectively. These differences are statistically significant at the 1%-level, employing t-tests controlling for sector and country.

Table 1. Credit quality indicators of zombie firms vs. healthy firms IFRS

Notes: This table shows, for the matched Orbis-AnaCredit sample, average numbers of healthy and zombie firms concerning the proportion of loans that are in default, non-performing, classified as IFRS stage 1, 2 or 3 under the IFRS reporting framework or as impaired with specific loss allowances under reporting frameworks other than IFRS 9 (GAAP).

To measure potential financial spillovers from zombie to healthy firms, in a second step we look at matched credit and firm balance sheet data. This allows us to compute the bank zombie share, which amounts to the outstanding nominal of loans held by zombie firms at a certain bank at a certain time, as a share of the total outstanding nominal held by all firms of that bank at that time. Compared to the existing literature, this bank-level measure is a novel statistic thanks to the granularity of our dataset. Using our zombie definition, in the period between Q3 2018 to Q4 2021, 1.81% of the outstanding nominal amount in loans at an average EA bank were held by zombie firms.

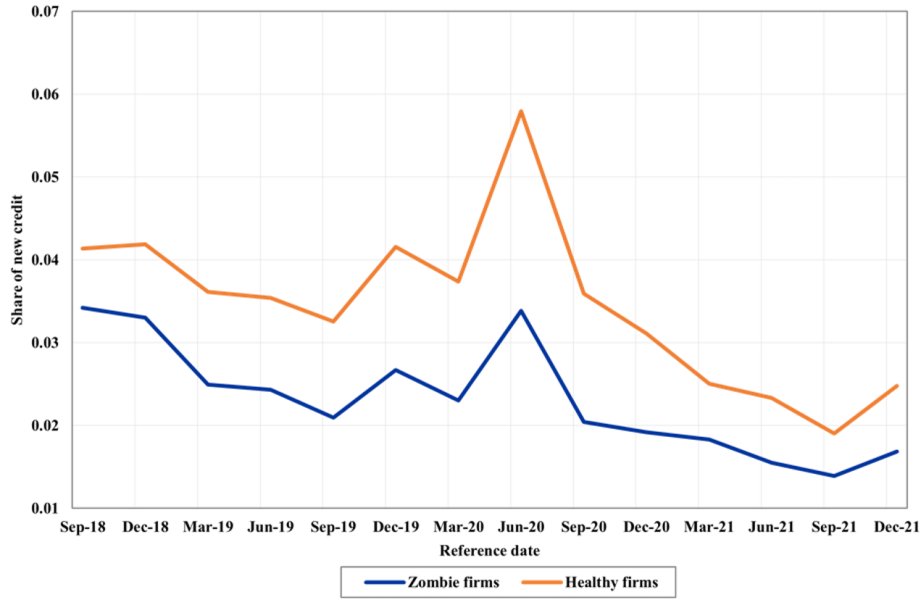

Our analysis, however, cannot confirm the existence of negative financial spillovers on credit conditions; neither for new credit, nor for interest rates. More specifically, regarding new credit, healthy firms receive significantly more new credit than zombie firms, see Figure 2. Furthermore, there is no negative spillover effect: Healthy firms in banks with a higher share of loans held by zombie firms (bank zombie share) do not receive significantly less new credit than healthy firms in banks with a lower zombie share.

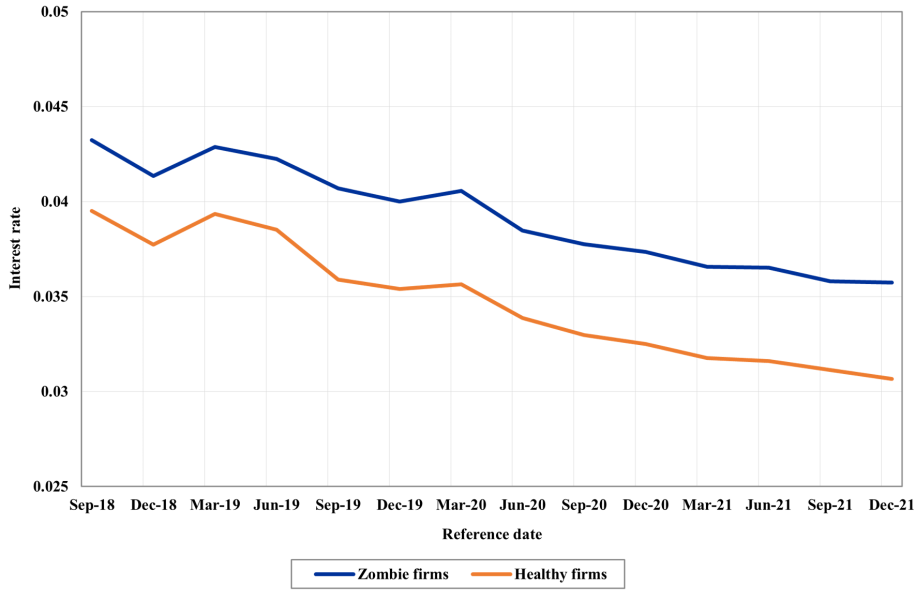

As regards interest rates, our analysis reveals several interesting results. First, interest rates paid by zombie firms are significantly higher than those paid by healthy firms, as shown in Figure 3. This contradicts the widely held notion that zombie firms would receive subsidised credit. Distinguishing firms based on their probability of default, we find one exception: Healthy firms rated C or worse pay higher interest rates than zombie firms with the same rating, suggesting that the subsidised credit argument applies only within the realm of firms that are indeed in very bad shape. Second, banks with a higher share of zombie firms charge significantly lower rates for both groups of firms. Third, in contrast to the two existing studies examining spillovers on interest rates in the EA (Acharya et al., 2019; Albuquerque and Roshan, 2023), there exists a spillover effect to healthy firms, but it is benefiting them. Healthy firms in banks with a higher zombie share pay significantly lower interest rates than firms with loans in banks with a lower zombie share. The spillover effect does not seem to depend on the credit quality of loans, as is examined using sub-samples of similarly rated firms. The total effect of the existence of zombie firms in a bank actually reduces the interest rates of healthy firms by up to 30%. These main conclusions are robust to using alternative zombie definitions and alternative fixed effect specifications.

Our results question the prevailing view that zombies indeed adversely affect healthy firms’ credit conditions and also that subsidised credit is a defining factor of them (Acharya et al., 2019; Andrews and Petroulakis, 2019). There are several possible explanations for this discrepancy of our findings with the literature. First, our data sources permit a more direct and granular measurement of interest rates and credit attributes on the bank, not the sector, level. Second, we look at an extensive sample of not only large, but also medium, small, and micro sized firms. Finally, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study that investigates financial spillovers from zombie to healthy firms including all EA countries, resulting in a strong sample size and potentially more representative results.

Figure 2. New credit healthy vs. zombie firms

Notes: The graph plots the sum of new credit divided by the total amount of credit at a specific quarter for the average zombie and healthy firm. The indicator is capped at a value of 1000 for healthy firms.

Figure 3. Average interest rate paid by healthy vs. zombie firms

Notes: This figure plots the interest rates paid by zombie and healthy firms from 2018 Q3 to 2021 Q4, averaged across all loans held by firms in either group.

On the one hand, the findings of this study seem like “good news” in terms of policy implications: Zombie firms receive less new credit and are charged higher interest rates than healthy firms, owing to the elevated credit risk that they pose, and an unambiguous adverse spillover effect on healthy firms is not discernible. Thus, our analysis provides an orientation for an important trade-off policymakers face: While policies like public support schemes for weaker firms are crucial in cushioning financial and economic shocks, e.g. during the Covid-19 pandemic, they can impede longer-term productivity growth by favouring the existence of zombie firms and in turn harm healthy firms through several transmission channels. Our results, however, suggest that financial spillovers on credit conditions, at least in the EA, should not be a major concern. Hence, policy interventions seem to pose fewer negative externalities than previously expected.

On the other hand, this does not mean that one can disregard the issue of zombie firms altogether. After all, this paper also highlights that zombie firms do constitute a non-negligible fraction of the economy in several EA countries. The mere existence of zombie firms suggests misguided lending incentives by banks or policy structures that allow artificially keeping inefficient firms alive. Furthermore, although zombie firms pay higher rates than healthy firms, it is not clear if these appropriately reflect their elevated credit risk. Even though zombie firms receive less new credit than healthy firms, they do receive new credit. Finally, while we find financial spillovers to be a less significant concern as the literature implied, real spillovers likely still exist, for instance through the competition channel, as the studies we cite above demonstrate in several contexts. For example, competition on the sector level could be distorted as zombie firms survive economic shocks that would have usually led to their exit. Thus, they deter entry of more productive firms into the market, leading to adverse real spillovers for healthy firms.

Our analysis covers a phase of low interest rates. Now that central banks have raised rates to combat high inflation, which strongly tightened credit conditions for firms, further policy-relevant questions arise: Did credit conditions tighten equally strongly for zombie firms? Can we now indeed expect a wave of zombie firm failures? Policymakers could view this scenario as a potential threat to financial stability, or as necessary creative destruction, like some authors suggest (Albuquerque and Roshan, 2023). Given these challenges, the existence of zombie firms in the EA and around the world remains an important issue that warrants further research.

Acharya, V. V., M. Crosignani, T. Eisert, and S. Steffen. 2022. Zombie Lending: Theoretical, International, and Historical Perspectives. Annual Review of Financial Economics 14:21– 38.

Acharya, V. V., T. Eisert, C. Eufinger, and C. Hirsch. 2019. Whatever It Takes: The Real Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy. The Review of Financial Studies 32:3366– 3411.

Albuquerque, B., and I. Roshan. 2023. The Rise of the Walking Dead: Zombie Firms Around the World. IMF Working Paper 23/125.

Andrews, D., and F. Petroulakis. 2019. Breaking the Shackles: Zombie Firms, Weak Banks and Depressed Restructuring in Europe. Working Paper 2240, European Central Bank.

Banerjee, R., and B. Hofmann. 2018. The Rise of Zombie Firms: Causes and Consequences. BIS Quarterly Review Sept. 2018, Bank for International Settlements.

Banerjee, R., and B. Hofmann. 2022. Corporate Zombies: Anatomy and Life Cycle. Eco- nomic Policy 37:757–803.

Blattner, L., L. Farinha, and F. Rebelo. 2023. When Losses Turn into Loans: The Cost of Weak Banks. American Economic Review 113:1600–1641.

Caballero, R. J., T. Hoshi, and A. K. Kashyap. 2008. Zombie Lending and Depressed Restructuring in Japan. American Economic Review 98:1943–77.

ECB Podcast. 2021. Bicycles, Bitcoin and Zombie Firms: Financial Stability in the Wake of the Third Wave.

Godby, R., and S. B. Anderson. 2016. Of ‘PIIGS’ and ‘GIPSIs’: Pre-Crisis Structural Imbalances, pp. 75–120. 1st ed. Verlag Barbara Budrich.

McGowan, M. A., D. Andrews, V. Millot, and T. B. Editor. 2018. The Walking Dead? Zom- bie Firms and Productivity Performance in OECD Countries. Economic Policy 33:685– 736.

Pelosi, M., G. Rodano, and E. Sette. 2021. Zombie Firms and The Take-up of Support Measures during Covid-19. Occasional Paper 650, Bank of Italy.

Schivardi, F., E. Sette, and G. Tabellini. 2022. Credit Misallocation During the European Financial Crisis. The Economic Journal 132:391–423.

Storz, M., M. Koetter, R. Setzer, and A. Westphal. 2017. Do We Want These Two to Tango? On Zombie Firms and Stressed Banks in Europe. Working Paper 2104, European Central Bank.