Increased investment in clean electricity generation in combination with a rising cost of carbon will most likely lead to higher electricity prices. We examine the effect from changing electricity prices on manufacturing employment. Based on firm-level data, we find that rising electricity prices lead to a negative impact on employment and investment in sectors most reliant on electricity as an input factor. Since these sectors are unevenly spread across countries and regions, the labour market impact will also be heterogenous, with the highest impact being felt in regions where energy-intensive industries are concentrated, such as Southern Germany and Northern Italy. We also identify an additional channel that leads to heterogeneous labour market outcomes. When electricity prices rise, financially constrained firms reduce employment more than less constrained firms. This implies a potentially mitigating role for monetary policy.

Reaching the ambitious climate goals set by the EU will require significant investment in clean electricity generation in combination with increased taxation of energy products. There are, however, legitimate concerns that this could lead to higher electricity prices and more broadly rising energy prices. Previous IMF (2019) research suggests that a $75 carbon tax would be needed by 2030 to keep global warming at 2° C and that this could increase electricity prices in Europe up to 20% depending on the emission intensity of generation. Whilst the overall impact of such a price increase is complex and remains debated, an individual manufacturing firm faces higher input costs and lower competitiveness when electricity prices increase. This leads to reduced employment and investment, predominantly within firms active in sectors most reliant on electricity as an input factor. It is therefore safe to say that rising electricity prices will have heterogenous effects on employment, with lower-skilled workers active in electricity-intensive manufacturing industries being more negatively affected. The beneficial aggregate impact of rising electricity prices in view of achieving the EU climate goals could therefore mask long-lasting negative and heterogeneous labour market effects for some workers and/or EU regions.

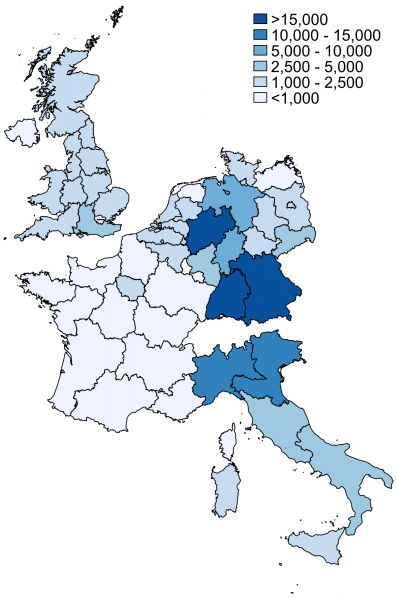

In Bijnens et al. (2021) we study over 200,000 manufacturing firms in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK over the period 2009 – 2017. We find that an electricity price increase of 20% would reduce employment by approximately 2% to 4% for the most impacted industries. An increase in the carbon tax to $75 a ton, as envisaged in the IMF estimates, could therefore lead to 150,000 affected jobs in the EU countries that we analyze. These jobs are either lost or need to be reallocated to other firms, industries and/or regions. We also find this impact to be highly heterogeneous. The impact is highest for industries generally regarded as electricity intensive (e.g., chemicals, metals and paper). We find the highest (most negative) country-wide impact for Belgium and the most adverse local impact in EU regions where energy- intensive industries are concentrated and electricity prices are expected to rise significantly, such as Southern Germany and Northern Italy (Figure 1).

These estimates might seem relatively contained in comparison to the millions of lost manufacturing jobs that have been successfully reallocated to the services industry during the European industrial transition of the past decades. There is nevertheless no room for complacency. First, the impact could very well reach beyond the direct 150,000 manufacturing jobs that we estimate. Based on recent insights and current carbon prices from the EU Emissions Trading System (the price hit a record high of €50 a ton on 4 May, a 50% increase since the start of the year), the price of carbon could be well over $75 a ton CO2 by 20302 and therefore the associated electricity price increase of 20% and 150,000 affected jobs can be viewed as a lower bound estimate.3

Figure 1. Negative employment impact on the manufacturing industry from rising electricity prices associated with a $75 carbon tax for different regions

Note: Geographical areas defined based on NUTS1 code. Employment figures for 2016. The total amount of affected jobs amounts to approx. 150,000. Source: Authors’ calculations.

Second, job destructions in the manufacturing sector have the potential to spill-over to the services sector through local interdependencies. According to past studies, destroying one well paid manufacturing job could indirectly lead to the destruction of 1 to 2.5 jobs in non-tradable services (hospitality, food, retail, …) in the immediate vicinity (Moretti 2010). Furthermore, any newly created services jobs that would result from this large-scale reallocation may not necessarily be in the same region where the adversely affected workers live nor for the same skill-set. Given the more reduced labour mobility for low-skilled workers, increasing electricity prices could therefore have long-lasting negative labour market effects for the affected regions and workers akin to the “China syndrome” coined by Autor et al. (2013) to describe the heterogenous exposure of US regions to rising Chinese import competition.4

Given these considerations, ensuring a positive public sentiment towards environment-related energy price increases will in all likelihood require that the transition to the EU climate goals be accompanied by targeted measures aimed at providing assistance to firms, workers, and communities that are more disproportionately affected. While this is traditionally a role for fiscal policy, there has been increased attention recently from monetary policy makers towards how climate change can affect the economy and the financial system.5 In our case, rising electricity prices are part of risks to the economy associated with the transition towards a carbon neutral economy. Rising electricity and more broadly energy prices could e.g., cause negative supply shocks, lead to stranded assets, and be a burden to employment and overall activity in some parts of the economy.

Our study also suggests a potential channel through which monetary policy could mitigate the negative employment effects arising from rising energy prices stemming from a carbon tax. More specifically, we find that financially constrained firms tend to reduce employment more when electricity prices rise compared to firms that are less financially constrained. This finding is aligned with established evidence that firms expected to be more financially constrained react more to monetary policy shocks as frictions in financial markets amplify the effects of monetary policy on borrowers with lower access to external financial resources.6

Autor, D. H., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. H. (2013). The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States. American Economic Review, 103(6), 2121-2168.

Autor, D. H., Dorn, D., Hanson, G. H., & Song, J. (2014). Trade adjustment: Worker-level evidence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4), 1799-1860.

Bernanke, B. S., & Gertler, M. (1995). Inside the black box: the credit channel of monetary policy transmission. Journal of Economic perspectives, 9(4), 27-48.

Bijnens, G., Hutchinson, J., Konings, J., & Saint Guilhem, A. (2021). The interplay between green policy, electricity prices, financial constraints and jobs: firm-level evidence. European Central Bank Working Paper No 2537.

Hutchinson, J., & Xavier, A. (2006). Comparing the impact of credit constraints on the growth of SMEs in a transition country with an established market economy. Small business economics, 27(2-3), 169-179.

IMF (2019). Fiscal Monitor: How to Mitigate Climate Change. International Monetary Fund. Washington.

Moretti, E. (2010). Local multipliers. American Economic Review, 100(2), 373-77.

The opinions expressed here are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions they are affiliated with.

The UK’s Zero Carbon Commission recently advocated a £75 carbon price by 2030. Some experts come to a significantly higher price. E.g., the Quinet-2 Commission in France computed that to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, the tax should be set at €69 in 2020, raising by more than 11% each year to reach €230 in 2030 and then more slowly at a 6% rate to be settled at €750 in 2050.

Specifically for Belgium, we calculated the affected jobs based on an alternative scenario from a Belgian sustainable energy research institute (€83 carbon price, a wholesale electricity price of €70 / MWh by 2030, in current prices) and found the impact to be 3 times higher than the impact based on the $75 scenario.

Autor et al. (2013) show that different U.S. regions were exposed differently to Chinese import competition and that “rising exposure increased unemployment, lowered labour force participation, and reduced wages in local labour markets.” Exposure to Chinese competition affected not only local manufacturing employment but also numerous other sectors. In Autor et al. (2014) they add “earnings losses are larger for individuals with low initial wages, low initial tenure, and low attachment to the labour force.” Pressure on China-exposed industries and regions led to the fact that a part of the labour force was worse off than before, even many years after the shock occurred.

See speech by ECB President Christine Lagarde on “Climate Change and Central Banking” at the ILF conference on Green Banking and Green Central Banking, 25 January 2021. In 2017, the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Finanical System (NGFS) was lauched to share best practices among Central Banks and Supervisors.

See Bernanke and Gertler (1995) and Hutchinson and Xavier (2006).