China could be the first major economy to issue a CBDC. We first provide an historical overview of this project, putting it in political perspective, then present its main features. We recall the strategic objectives put forward by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) for the e-Yuan, discuss them and ask whether other objectives may not matter more. We conclude that the e-Yuan could be particularly useful for the Chinese government.

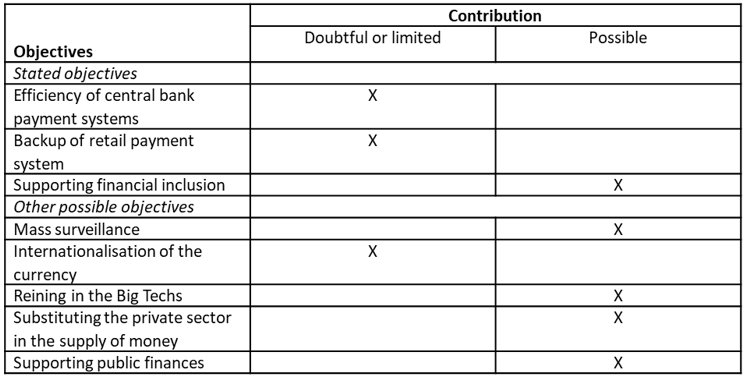

Table 1: Contribution of the e-Yuan to People’s Bank of China (PBoC) objectives

The PBoC claims a pioneering role in the work on CBDC, which it started as early as 2014. To put this work in a political perspective, the PBoC states that “Since the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, following the guidance of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, the PBoC has made solid efforts to advance the pilot program of e-Yuan research and development. Adhering to market-based and law-oriented principles while staying committed to people’s interest, the PBoC has advanced the development of e-Yuan in line with China’s conditions through three stages: theoretical research, closed-loop testing, and pilot application” (PBoC, 2022).

In 2016, the PBoC established the Digital Currency Institute and proposed the top-level designs and fundamental features of e-Yuan (PBoC, 2021). At the end of 2019, the PBoC started pilot tests in four cities. Later on, pilot areas were progressively expanded to cover 23 cities. In order to favor the adoption of the e-Yuan during these pilot tests, many promotional campaigns were organised in the pilot areas, in particular with giveaways. An important milestone was reached in January 2022, in the run-up of the Beijing Winter Olympics, with the availability of the «e-Yuan pilot version» on Android and Apple, and shortly after on WeChatPay and Alipay. In the meantime, use cases were progressively expanded, for example to the payment of public transportations, taxes, medical care, public aids, etc.

As explained by Changchun Mu, Director General of the PBoC’s Digital Currency Institute (BIS, 2023) although the e-Yuan will be legal tender, its use by citizens cannot be made mandatory, hence the need to make the e-Yuan more appealing and user-friendly. That is why, since the launch of the e-Yuan pilot version early 2022, the PBoC has released numerous versions of its App.

At the time of writing this article (October 2023), the e-Yuan was still in the pilot stage and no decision had been announced regarding a timetable for a possible “go live” of the e-Yuan. But the stance of the PBoC is clear: “The train has left the station. The PBoC believes that CBDCs will be the answer for the digital era” (Mu, 2022b).

According to the PBoC, at the end of June 2023, the pilot areas had (cumulatively) recorded 950 million e-Yuan transactions for a total value of RMB 1.8 trillion ($ 250 billion), with 120 million wallets being opened. These figures may look substantial but the total amounts held in e-Yuan still represent a small proportion of the monetary aggregates: e-Yuan, which was included in M0 from December 2022, accounted for only 0.16 % of it at end-June 2023 (PBoC, 2023).

If it is officially launched, the e-Yuan would share many features with other CBDC projects: it would be a central bank’s liability to the public, with legal tender, settlement upon payment, non-remuneration and no collection of fees. Also, the e-Yuan would be based on a two-tiered architecture whereby the PBoC issues the e-Yuan to authorized operators, and authorized operators distribute the e-Yuan to end users. The e-Yuan would have a dual off-line payment function allowing payments to be made between two phones or two cards.

To a certain extent more originally, the PBoC has adopted the so-called “loosely-coupled account linkage design” which means that users could apply for e-Yuan wallets without opening a bank account (Mu, 2022b). According to the concept of “managed anonymity (see below), different categories of wallets could be opened, with different KYC levels. For instance, wallets of the lowest category (category 4) could be opened with only a mobile phone number, but with relatively low amount limits: 2 000 yuans ($ 280) per transaction, 5 000 yuans per day and a maximum balance of 10 000 yuans. Users could upgrade their wallets to an upper category by providing more KYC information such as ID or bank account information (Mu, 2022a).

Although the e-Yuan is so far designed for domestic retail payments, the PBoC states it will “actively respond to initiatives of the G20 and other international organisations to improve cross-border payments, and explore the applicability of CBDC in cross-border scenarios” (BIS, 2022). Referring to the concerns that a cross-border use of the e-Yuan might raise, the PBoC has introduced three principles that “shall be observed before conducting any CBDC cross-border experiments” (Mu, 2022b):

The PBoC has put forward three strategic objectives (Mu, 2022b).

However, the Chinese private retail payment system is already very efficient, in fact more efficient than in many developed economies. In particular, QR-code real-time payments, accessible on a 24/7 basis, including offline, have been available in most parts of the country since 2015, through the networks of Alipay and TenPay.

The PBoC argues that AliPay and TenPay have become important retail payment infrastructures, so that any failure, be it of a financial or technical nature, will dramatically impact payment system operation, and even introduce systemic risks. However, the appropriate response to this oligopoly situation would rather seem to be to introduce more competition in the payment services industry.

These are probably more valid motives, since the PBoC indicates that between 10% and 20% of the population are unbanked or underserved. However, there are other ways than launching a CBDC to support financial inclusion and equal access to digital payment, as the example of M-Pesa in Kenya has shown.

All in all, none of the three above-mentioned strategic objectives put forward by the PBoC seems fully compelling.

There are five other possible motives for an e-Yuan. The three first ones listed below have received wide media coverage; the two last ones are seldom mentioned.

The PBoC stresses that the e-Yuan system collects less transaction information than traditional electronic payment systems and does not provide information to third parties or other government agencies unless stipulated otherwise in laws and regulations. In reply to those who note that a phone number will easily allow to access the identity of the users, the PBoC underlines that the Personal Information Protection Law, recently enacted in China, prevents phone companies from communicating this information to e-Yuan distributors or to the central bank. However, there are other ways of getting the names of telephone subscribers. Furthermore, if a programmability of the e-Yuan was established, it could be used as an easy means of depriving some beneficiaries of payments, such as those of social benefits, in their favour.

Although, as a country, China has been the world leading exporter since 2009, only around a fifth of its foreign trade is currently denominated in its currency and the share of the yuan in global official holdings of foreign exchange reserves is close to 2%. The corresponding shares are respectively slightly less than a half for the euro area and a little more than a fifth for the euro. So, it is unsurprising that the Chinese authorities should try to internationalize their currency (Cipriani et al., 2023; Kumar, 2023). However, capital flow management measures impose narrow limits to this internationalisation. The other main obstacles to the internationalisation of the yuan, starting with the absence of both a genuine rule of law and of developed capital markets, would also remain if an e-Yuan is launched. Nonetheless, the PBoC has been actively exploring the possibilities of a cross-border use of CBDCs in the recent years, notably by participating in Project mBridge with the BIS Innovation Hub and the Hong-Kong Monetary Authority, the Bank of Thailand and the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates (BIS Innovation Hub, 2022). The PBoC has also been partnering in the work of the G20 on CBDC interoperability for cross-border payments (FSB, 2023). Through its participation in international projects and groups, China could play a disproportionate role, in comparison with the one played by its currency on the international stage, in the definition of international standards for CBDC. However, whether other countries, starting with the U.S., would let China play such a role, is unclear. It is also not warranted whether having a « first-mover advantage » in being the first major economy to launch a retail CBDC would give the Chinese currency a cutting edge over its competitors to become a significant international currency. Indeed, Suarez and Lanzolla (2005) argue that developing such a first-mover advantage is unlikely when ‘technology leads’ and very unlikely when ‘the market gets rough’. Chorzempa (2021) notes that these two adverse conditions are met in the digital currency space.

In the Chinese case, these would be the BATX (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, Xiaomi), especially Alibaba (which owns AliPay) and Tencent (which owns TenPay). In fact, as indicated above, the biggest challenge for the BATX would be to let competitors enter the markets they operate in, while making interoperability mandatory. However, such a recourse to market pressures could run counter to the economic and political options of the Chinese government.

This process is usually referred to as “disintermediation”, and involves the substitution of CBDC for deposits. This risk largely explains why, in economies where the launch of a CBDC is considered, limits to individual holdings and a zero interest rate on CBDC are envisaged. However, in the Chinese case, individual holding limits could be set at pretty high levels, and even be illimited in the case of wallets of category 1 (Turrin, 2022).

Such an objective is very seldom mentioned for issuing a retail CBDC (see however, Pfister, 2022, 2023). It rather appears in some studies as a by-product of issuing a CBDC (see e.g. Burlon et al., 2023). In fact, issuing a retail CBDC should quasi inevitably have three positive effects on public finances. To start with, the production and maintenance of a retail CBDC should be less costly than that of cash for which it would substitute. The second effect is that the substitution of retail CBDC for cash could reduce tax evasion. The third effect would be that the central bank would have to find an asset to invest in as a counterpart of issuing retail CBDC that would substitute for deposits. An obvious choice would be public bonds. In turn, this increased holdings of public bonds offers the government two advantages. Firstly, the government is financed for free to the extent that interests paid on the public bonds held by central bank are fully returned to the government in the form of increased payments of taxes and dividends. Secondly, insofar as the aggregate holding of CBDC by the public would most likely increase in the medium to long run, as has been the case for cash in the past, this part of the public debt never has to be redeemed and in fact increases as the use of CBDC expands.

Although its role in increasing social welfare would be unclear, especially in view of the already high-level in the quality and quantity of payment services in China, the roll-out of a digital yuan could be useful for the Chinese government, especially in pursuing objectives which are not officially put forward.

Bank for International Settlements (2022), CBDCs in emerging market economies, April.

https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap123.pdf.

Bank for International Settlements (2023), The process of technological innovation at central banks, March. https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap123.pdf.

Bank for International Settlements Innovation Hub (2022), Project mBridge: Connecting economies through CBDC, October. https://www.bis.org/publ/othp59.pdf.

Bech M., Faruqui U., Ougaard F., Picillo C. (2018), Payments are a-changin’ but cash still rules, BIS Quarterly Bulletin, March, 67-80. https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1803g.pdf.

Burlon, L., Montes-Galdón, C., Muñoz, M.A., & Smets, F. (2022), The optimal quantity of CBDC in a bank-based economy, European Central Bank, Working Paper 2689.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2689~846e464fd8.en.pdf.

Financial Stability Board (2023), G20 Roadmap for Enhancing Cross-border payments – Priority actions for achieving the G20 targets. https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P230223.pdf.

Khiaonarong T., Humphrey D. (2023), Measurement and Use of Cash by Half the World’s Population, International Monetary Fund, Working Paper 23/62, March. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/03/17/Measurement-and-Use-of-Cash-by-Half-the-Worlds-Population-531077.

Kumar A. (2023), Domestic and global implications of China’s digital currency, Intereconomics, July/August. https://www.intereconomics.eu/pdf-download/year/2023/number/4/article/domestic-and-global-implications-of-china-s-digital-currency.html.

Mu C. (2022a), Balancing privacy and security: theory and practice of the E-CNY’s managed anonymity, PBOC Policy Research, November. http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3935690/3935759/4696666/2022110110364344083.pdf.

Mu C. (2022b), Theories and Practice of exploring China’s e-CNY, PBOC Policy Research, December.

http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3935690/3935759/4749192/2022122913350138868.pdf.

People’s Bank of China (2021), Progress of Research & Development of E-CNY in China, July.

http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3688110/3688172/4157443/4293696/2021071614584691871.pdf.

People’s Bank of China (2022), Pressing ahead with the pilot program of E-CNY R&D, October.

http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3688006/4671762/4688130/index.html.

People’s Bank of China (2023), financial statistics report H1 2023, July.

http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3688247/3688978/3709137/4989745/index.html.

Pfister C. (2023), Monetary Sovereignty in the Digital Currency Era, in Digital Assets and the Law: Fiat Money in the Era of Digital Currency, edited by Professor Filippo Zatti and Rosa Giovanna Barresi, Routledge-Giappichelli, forthcoming.

Pfister C. (2023), Motives for a retail CBDC: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly?, 2023, International Review of Financial Services, forthcoming.

Turrin R. (2022), China’s new digital yuan or e-CNY App by the PBOC earns five stars out of five in my review, https://www.linkedin.com/posts/turrin_pboc-pboc-china-activity-6889547103731892225-zxDg.