The opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of Bank of Finland or the Eurosystem. All errors are our own. This article is based on our working paper “Is globalization the root cause of declining inflation?

In 2021, most countries experienced a sharp increase in inflation which shows no signs of dying soon. To a large extent this surge was unexpected, at least if we rely on various surveys on inflation expectations, not to speak of inflation expectations derived from asset prices. These developments questioned the standard ways of analyzing inflation and specifying the respective behavioral equations. In particular, this is true with inflation expectations, which for more than fifty years have been the key ingredient of the Phillips curve-based interpretation of inflation. In a recent paper, Jeremy Rudd (2021) criticized the current state of affairs and pointed out that many observed regularities are not consistent with this standard specification. Moreover, he pointed out that many behavioral patterns are state-dependent, which means that the transmission of costs may well depend on the specific regime of excess demand. Similar points have been put forward in the recent BIS annual report (BIS 2022).

In the traditional analysis of inflation, globalization has a very limited role. The key variables, inflation, inflation expectations and the output gap/real marginal costs are all country specific. Oil prices represent (occasionally) the only “global variable”. Recently, however, there has been a growing interest in assessing the eventual globalization effects. Here, we can mention the studies of Pain et al. (2008), ECB (2021) and the European Parliament (2015). The results of all these studies have been rather diverse and one cannot really find one which would have provided strong evidence on the behalf of the idea that globalization is of prime importance in terms of inflation. Thus, also the abovementioned Pain et al. (2008) and ECB (2021) studies end up with rather marginal globalization-induced inflation effects. Perhaps the strongest effects come out in the study of Amiti et al (2018), which focusses on the effect China’s WTO membership on US prices. A useful source is also Bernhofe et al. (2013) which studies the effects of container revolution on trade. According to their study, the effects of this technical change are much larger than the effects of free trade agreements or the GATT. There are many reasons for these conflicting results (e.g. missing role of contestable market effects, see e.g. Auer (2017)), which obviously represent a big challenge for empirical analysis.

In the immediate post WWII period individual countries’ supply was largely constrained by the productive capacity of the domestic economy. That is because of the following reasons:

A big change took place – starting in the early 1980s – when China abandoned the old-style communist economic system and provided seemingly an unlimited amount of cheap labor for domestic and international entrepreneurs. In Charles Goodhart’s (2020) words, China’s wage rate had become some sort of labor supply curve for the global economy. In early 1990, the Eastern European countries also followed suit, further pushing the capacity frontier further away from previous single country levels.

We have analyzed the globalization effects in several different ways. First we have looked at the dispersion of inflation and output growth rates of different set of countries including the whole World, USA, OECD, Euro area and Finland. Besides that, we have looked the relative prices for different countries. The idea in these analyses is quite simple: globalization should make time paths of inflation more similar because all countries would in the end face the same highly elastic global supply curve instead of facing country-specific supply and capacity constraints. As for relative prices, we would expect that inflation rates for the tradeable goods behave quite differently from the non-tradeable goods (mainly services) because the latter do not benefit from globalization effects.

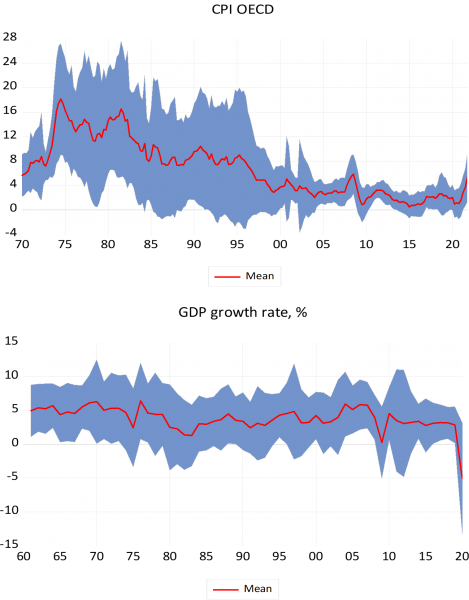

The data are very much consistent with the globalization interpretation. The dispersion of inflation (Figure 1) has come down dramatically in the late 1990s and stayed very small after that (until the beginning of the Convid-19 crisis). By contrast the dispersion of output growth stayed the same for the whole 1960-2020 period. The time of events fits very well with different globalization indicators such as goods delivered by postal services, goods ordered and paid by electric payment methods, goods ordered by the Internet, the KOF index of globalization, the FDI data and the export market share of China. A remarkable feature in the indicators is that they all show that the big change in globalization took place just in the 1990s and this is also consistent with the development of tariffs, freight costs and so on.

Figure 1: Dispersion (+/-1*SD) of inflation and GDP growth rates in the OECD countries

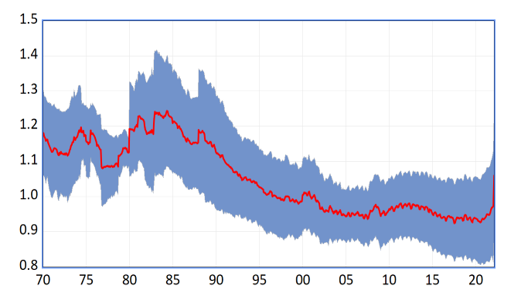

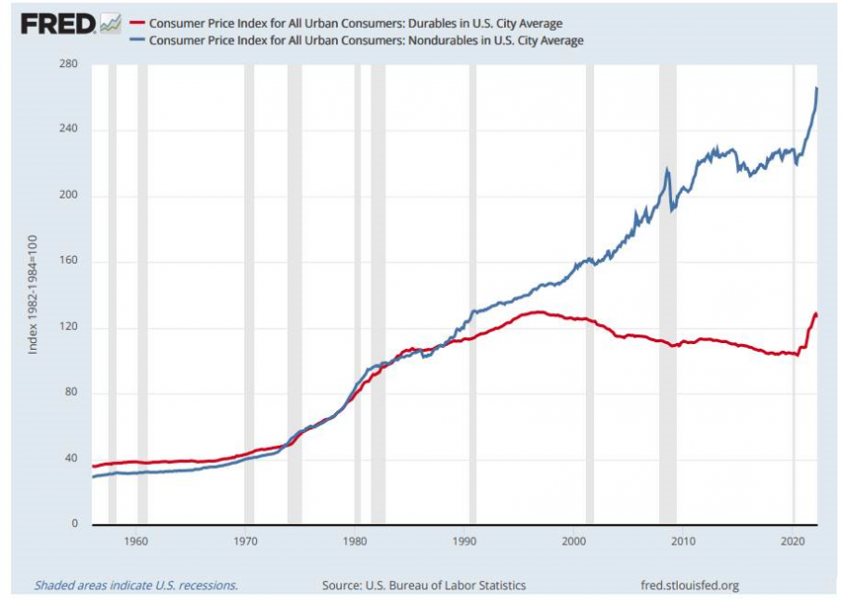

With the relative prices, we find that until the end of 1980 inflation rates for different commodities were very similar but after that a growing difference emerged between tradeable and non-tradeable commodities (Figure 2). Similar pattern appears with durable and non-durable goods (Figure 3), which obviously reflects the same mechanism.

Figure 2: Relative prices (+/-1*SD) between goods and services in the World panel data

Figure 3: Relative prices of durables and nondurables in the US

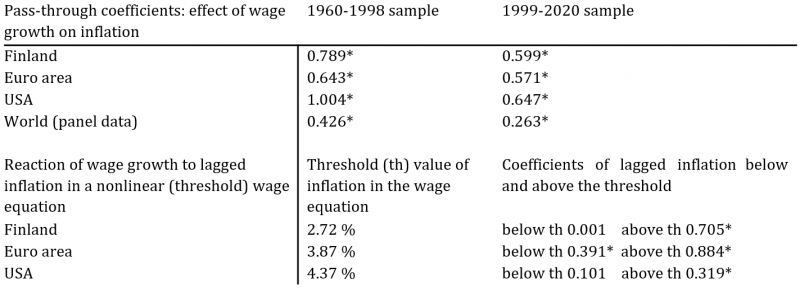

We also estimated several inflation and wage growth equations to see how our globalization proxies perform using data from Finland, Euro area, USA and panel data for all World countries. The results were quite clear-cut: increased globalization always depressed the inflation rate in a nonmarginal way. In the same way as Kolaches and Moessner (2021), we found that the pass-through from wages to prices has become much smaller over time (upper part in Table 1). The globalization effects also showed up in wage growth, even though we controlled things like the labor union participation rate.

As for wages, the interesting thing was the observation that the reaction of wages to inflation has also been far from constant being very much different in low and high inflation regimes (cf. Table 1). Thus, in a low inflation regime, the effect is very small – even insignificant – while in a high inflation regime it comes close to one. The critical (threshold) values were something like 3-4 per cent suggesting that in the past low inflation regime there were no elements of wage-price spiral opposite to the pre-1990s experiences.

Table 1: Regime changes in some key parameters of inflation – wage growth relationship

First four lines illustrate the effect of wages on inflation while the last three lines illustrate the effect of past inflation on wage growth in a nonlinear (threshold) wage equation where the size of inflation response depends on the rate of inflation. The data cover 1964q1-2021q4. * indicates statistical significance at the 5 per cent level. The parameters are derived from inflation and wage growth equations which include the output gap, the unionization rate and (when necessary) fixed country and time effects. For details, see Hukkinen & Viren (2022).

Most analyses on globalization effects have focused on realized trade flows and because these flows have not increased in an excessive way, particularly after 2007, one might end up with the conclusion that globalization effects on inflation are only of marginal importance. The problem is that trade flows are probably a poor indicator of all features and consequences of globalization, ignoring e.g. contestable market effects, capacity constraints, transportation costs, payment costs, tariffs, changes in labor market institutions and the “IT revolution”. Obviously, it is very difficult to consider all of these elements but our study suggests that incorporating some of these produces much bigger effects, which seem also to match the more recent data.

Amiti, M., M. Dai, R. Feenstra and J. Romalis (2018) How Did China’s WTO Entry Affect U.S. Prices? Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports No. 817. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr817.pdf?la=en

Auer, R., C. Borio and A. Filardo (2017) The globalization of inflation: the growing importance of global value chains, BIS Working Papers No 602. https://www.bis.org/publ/work602.pdf

Bernhofen, D. , Z. El-Sahli and R. Kneller (2013) Estimating the effects of the container revolution on world trade, Lund University, Economics Department Working Paper 2013:4. https://project.nek.lu.se/publications/workpap/papers/WP13_4.pdf

BIS (20221) BIS Annual Economic Report June 2022. https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2022e.pdf

ECB (2021) The implications of globalization for the ECB monetary policy strategy. ECB Occasional Paper 263. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op263~9b56a71297.en.pdf

European Parliament (2015) Is globalization reducing the ability of central banks to control inflation. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/105466/IPOL_IDA(2015)563476_EN.pdf

Goodhart, C. and M. Pradhan (2020) The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival. Palgrave. Macmillan, London.

Kohlscheen, E, and Moessner, R. (2021) Globalisation and the Decoupling of Inflation from Domestic Labour Costs. CESifo Working Paper 9281. https://www.cesifo.org/en/publikationen/2021/working-paper/globalisation-and-decoupling-inflation-domestic-labour-costs

Pain, N., I. Koske and M. Sollie (2008) Globalisation and OECD Consumer Price, OECD Economic Studies 44. https://www.oecd.org/economy/42503918.pdf

Peneva, E. and J. Rudd (2015) The Passthrough of Labor Costs to Price Inflation, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2015-042. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, http://dx.doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2015.042

Reis, Ricardo (2021) The People versus the Markets: A Parsimonious Model of Inflation Expectations,” CEPR Discussion Papers 15624.

Rudd, J. (2021) Why Do We Think That Inflation Expectations Matter for Inflation? (And Should We?): Federal Reserve Board. Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2021-62. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2021062pap.pdf

Stock, J. and Watson, M. (2021) Slack and Cyclically Sensitive Inflation. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/stock/files/stock_watson_slack_and_critically_sensitive_inflation _070918.pdf