This policy brief is based on ECB Working Paper 3160, also forthcoming in the Journal of Business & Economic Statistics. The views expressed in this SUERF Policy Brief are those of the authors and should not be reported as representing the views of the European Central Bank (ECB), De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) or the Eurosystem.

Abstract

Using a novel macro-finance model we infer jointly the equilibrium real interest rate r*, trend inflation, interest rate expectations, and bond risk premia for the United States. In the model r* plays a dual macro-finance role: as the benchmark real interest rate that closes the output gap and as the time-varying long-run real interest rate that determines the level of the yield curve. Our estimated r* declines over the last decade, with estimation uncertainty being relatively contained. We show that both macro and financial information is important to infer r*. Accounting for the secular decline in interest rates renders term premia more stable than those based on stationary yield curve models.

The natural real rate of interest, r*, plays a prominent role in macroeconomics and in finance: from a macro perspective, it is the real interest rate consistent with the economy operating at its potential level; from a finance perspective, it is the expected short-term real rate in the far future and thus, together with long-term inflation expectations (π*), an anchor for the expectation of nominal short-term rates (i*) and the entire yield curve. The natural rate is, however, unobserved and needs to be inferred from a model. The literature has typically addressed its macro and finance roles separately and the two approaches “can lead to very different estimates of the natural rates and risk premia and the associated historical interpretations and narratives” as stressed recently by Davis et al. (2024); a finding that they coin the “natural rate puzzle”.

In our new paper (Brand et al., 2026), we address this puzzle by introducing a novel macro-finance model where the natural real rate of interest fulfils its dual macro-finance role. Using this model, we infer jointly the equilibrium real interest rate, trend inflation, interest rate expectations, and bond risk premia for the United States. The first model component, the “macro module”, defines r* as the real rate of interest that closes the output gap asymptotically. The natural rate is linked to the trend in output growth and a non-growth component, similar to Laubach and Williams (2003). However, unlike their paper, we explicitly model and estimate trend inflation as well as model-consistent inflation expectations. The gap between the ex-ante real rate of interest and the natural real rate drives the output gap in the IS equation and, thereby, inflation through the Phillips curve. The second component of our model is an arbitrage-free affine Nelson–Siegel (AFNS) term structure model for the nominal yield curve. It features a level factor that incorporates a stochastic trend determined by the equilibrium nominal short-term rate i* (r* plus trend inflation, π*). The slope and curvature factors, by contrast, are mean reverting as suggested by statistical tests.

The estimation of our integrated macro-finance model is based on quarterly data from 1961Q2 to 2019Q4 for the United States, using a Bayesian approach.

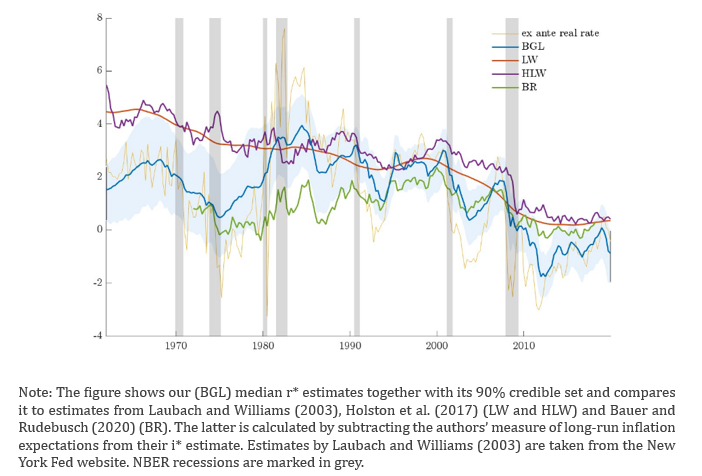

Our r* estimates for the US are shown in Figure 1. These estimates exhibit a distinct rise and fall over the past six decades, with a particularly steep decline following the Global Financial Crisis, as opposed to the steady decline reported by Holston et al. (2017), and more in line with Del Negro et al. (2017).

Figure 1. Comparison of r* estimates

The literature broadly agrees on a general downward trend in r* and its fall to levels around zero in the wake of the financial crisis. The drivers underlying r* explored in the literature include lower productivity and potential output growth, a rise in risk aversion, declining growth rates in the working-age population, rising savings in anticipation of longer retirement periods (at global level), safe-asset scarcity, and possibly increasing inequality and firm profits (Caballero et al., 2017; Gourinchas and Rey, 2019; Papetti, 2019; Rachel and Summers, 2019; Mian et al., 2020, among many others). However, as our model estimates determinants of r* as latent factors, it allows only indirect and heuristic insights into the role of low-frequency drivers of r*. The demographic transition, for example, would be captured through indirect effects on potential output growth through lower working-age population growth and non-growth factors, such as higher savings in anticipation of longer retirement periods.

Despite using the same semi-structural macroeconomic relations as in Laubach and Williams (2003), our r* estimates imply a real rate gap (actual real rate minus r*) that is distinctly cyclical, contrasting with the highly persistent estimates of their paper. This difference arises because our stipulated yield curve model endogenizes the real rate and renders the real rate gap stationary, while the real rate in Laubach and Williams (2003) is exogenous and the real rate gap can vary arbitrarily. In particular, we estimate r* to have been lower in the 1960s and 1970s and after the Global Financial Crisis than in Laubach and Williams (2003).

As regards estimation uncertainty, our natural rate path is also surrounded by measurably narrower uncertainty than usually implied by the semi-structural approach originating from Laubach and Williams (2003). In that original approach, filtering uncertainty for r* estimates using US data can be as large as eight percentage points (Fiorentini et al., 2018). By contrast, our model provides more precise estimates of r*, with narrower uncertainty bands (90% uncertainty bands are smaller than 3 percentage points).

Our set-up with a complete term structure module allows for specification analysis regarding the question of whether longer-maturity rate gaps are more adequate drivers of the output gap than the standard short-term real rate gaps. We find that longer-maturity (e.g. 10-year) real rate gaps explain output gaps better than traditional short-term measures, highlighting the relevance of the yield curve in macroeconomic dynamics.

Moreover, we illustrate the statistical relevance of variables that inform r* estimates. Historical decompositions suggest that the information content of all observables of the model are relevant for estimating r*: yields, macroeconomic and survey data.

Finally, we implement two key robustness checks. First, we check the robustness of our r* estimates regarding the zero-lower-bound period: when switching to a “shadow-rate” specification of our model, the resulting natural rate series is more volatile but shows the same low-frequency variation as in our baseline model. The resulting estimate of the shadow rate displays similar dynamics to that of Wu and Xia (2016), yet its trough is less negative than their estimate and uncertainty is sizeable. A second robustness check addresses real-time r* uncertainty. Pseudo real-time estimation of r* reveals considerable stability of estimates over estimation vintages, with limited variation in the posterior median point estimate of r* for shorter samples.

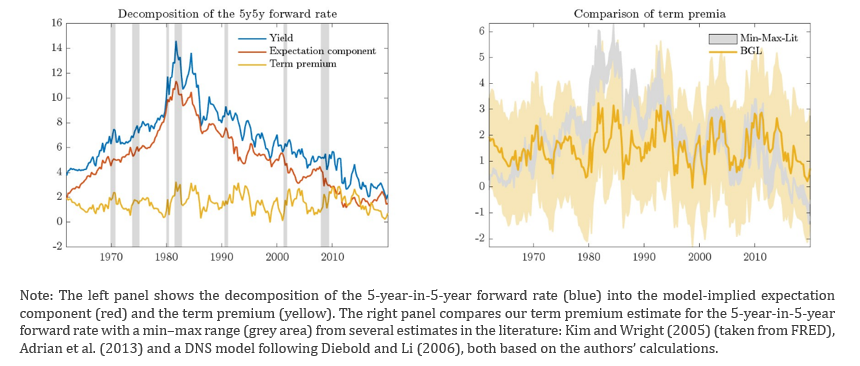

Accounting for the stochastic trend in interest rates affects the estimated behavior of term premia. We find that term premia exhibit more cyclical behavior rather than the persistent decline implied by stationary term structure models. The yellow lines in Figure 2 display our term premia estimates. Comparing these estimates with the range of those from stationary term-structure models illustrates that the former are less trending than the latter.

Figure 2. 5-year-in-5-year forward term premium estimates

By integrating macroeconomic and financial perspectives, our analysis resolves the inconsistencies highlighted in prior studies and provides a unified framework for estimating r*. The findings suggest that r* serves as a critical anchor for both yield curve dynamics and macroeconomic stabilization. Future extensions of this research could include inflation-linked bonds or the impact from central bank asset purchase programs.

Adrian, T., Crump, R. K., and Moench, E. (2013). Pricing the term structure with linear regressions. Journal of Financial Economics, 110(1), 110–138.

Bauer, M. D., and Rudebusch, G. D. (2020). Interest rates under falling stars. American Economic Review, 110(5), 1316–1354.

Brand, C., Goy, G., and Lemke, W. (2025). Estimating the natural rate of interest in a macro-finance yield curve model. ECB Working Paper No. 3160. European Central Bank. Also forthcoming in Journal of Business & Economic Statistics. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2025.2561409

Caballero, R. J., Farhi, E., and Gourinchas, P.-O. (2017). Rents, technical change, and risk premia accounting for secular trends in interest rates, returns on capital, earning yields, and factor shares. American Economic Review, 107(5), 614–620.

Davis, J., Fuenzalida, C., Huetsch, L., Mills, B., and Taylor, A. M. (2024). Global natural rates in the long run: Postwar macro trends and the market-implied r* in 10 advanced economies. Journal of International Economics, 149, 103919.

Del Negro, M., Giannone, D., Giannoni, M. P., and Tambalotti, A. (2017). Safety, liquidity, and the natural rate of interest. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2017(1), 235–316.

Diebold, F. X., and Li, C. (2006). Forecasting the term structure of government bond yields. Journal of Econometrics, 130(2), 337–364.

Fiorentini, G., Galesi, A., Pérez-Quirós, G., and Sentana, E. (2018). The rise and fall of the natural interest rate. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 13042.

Gourinchas, P.-O., and Rey, H. (2019). Global real rates: A secular approach. BIS Working Paper No. 793. Bank for International Settlements.

Holston, K., Laubach, T., and Williams, J. C. (2017). Measuring the natural rate of interest: International trends and determinants. Journal of International Economics, 108, S59–S75.

Kim, D. H., and Wright, J. H. (2005). An arbitrage-free three-factor term structure model and the recent behavior of long-term yields and distant-horizon forward rates. FEDS Working Paper 2005-33. Federal Reserve Board.

Laubach, T., and Williams, J. C. (2003). Measuring the natural rate of interest. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(4), 1063–1070.

Mian, A. R., Straub, L., and Sufi, A. (2020). The saving glut of the rich. NBER Working Paper No. 26941.

Papetti, A. (2019). Demographics and the natural real interest rate: Historical and projected paths for the euro area. ECB Working Paper No. 2258.

Rachel, Ł., and Summers, L. H. (2019). On secular stagnation in the industrialized world. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2019.

Wu, J. C., and Xia, F. D. (2016). Measuring the macroeconomic impact of monetary policy at the zero lower bound. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 48(2–3), 253–291.