This brief is based on NBER Working Paper 34107. The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the IMF, its Executive Board, or management.

Abstract

In a recent paper (here), we show the key, yet overlooked, role played by the legacy of a high inflation history on the strength of the monetary policy response to inflationary shocks. To rationalize this, we propose a New Keynesian model that diverges from the existing workhorse model by adding path-dependence (to an otherwise forward-looking model) and potentially imperfect central bank credibility. We show that achieving low inflation (i.e., hitting the inflation target) requires more aggressive monetary policy reactions, and is costlier from an output point of view, when individuals’ past inflationary experiences shape their inflation expectation formation. In turn, we support this empirically, by providing evidence of the need for these two theoretical additions. We find that countries that experienced a high level of inflation prior to adopting the IT regime tend to respond more aggressively to deviations of inflation expectations from the central bank’s target. We also point out the existence of a credibility puzzle, whereby the strength of a central bank’s monetary policy response to deviations from the inflation target remains broadly unchanged even as central banks gain credibility over time. In short, a country’s inflationary past casts a long and persistent shadow on central banks’ policy decisions.

The implicit use of Taylor rules as central banks’ reaction functions to shocks (usually within the context of inflation targeting, IT), is now well established as the key institutional underlying monetary policy framework. In fact, it has become the workhorse for the efficient conduct of monetary policy in central banks in advanced economies and in an increasing number of emerging markets, and even in developing economies. There is a vast literature, both theoretical and empirical, focusing on the workings of the IT monetary policy framework and the dynamic response of key macroeconomic variables. Yet, all these studies rest, among others, on two key assumptions (e.g., Woodford, 2003). First, inflation targeting central banks’ reaction function is not path-dependent, in the sense that countries’ characteristics prior to the adoption of IT, in particular the history of high inflation, do not affect the central bank’s monetary policy rule. Second, central banks are perfectly credible, that is, that central banks have perfectly anchored inflation expectations. In our paper we revisit these assumptions theoretically and empirically. Theoretically, we embed path dependence in an otherwise standard Dynamic New Keynesian (NK) model. We then estimate Taylor rules for 32 inflation targeting countries, both advanced economies and emerging markets, and explore how a country’s past inflation shapes central bank’s monetary policy rule.

To explore the theoretical implications of past inflation, we expand an otherwise standard dynamic NK model to allow for individuals’ past inflationary experiences to affect their inflation expectation formation. We show that, in such cases, achieving the inflation target becomes more costly in terms of lost output and requires a more hawkish monetary stance relative to a rational expectations benchmark. We also show that although expectations are exclusively shaped by events occurring in the past, the cost of inflation stabilization depends not only on how agents discount the past but also on how they discount the future. Specifically, if a prior inflationary experience leads people to believe that marginal costs will remain high in the future, optimally, the central bank will have to pre-emptively cool the economy to prevent inflation in the present. This requires inducing a negative output gap. The cost in terms of lost output depends on (i) the severity of the past inflationary exposure, with larger exposure amplifying the cost; (ii) the recency of the exposure, as more recent episodes weigh more heavily on expectations; (iii) the persistence of the memory of the exposure, which prolongs the economic effects of inflationary history; (iv) the degree of price stickiness, with stickier prices exacerbating the output loss; and (v) the subjective discount factor. The latter suggests that, even though experienced learning is by definition backward-looking, the magnitude of the cost of inflation stabilization depends also on the rate at which people discount the future. This is because this determines their present value of the expected size of marginal costs in the future. Thus, both backward- and forward-looking issues are relevant in equilibrium.

Moreover, in equilibrium, the nominal interest rate needs to be above its steady-state level throughout the transition. That is, under experienced learning, inflation stabilization requires a more hawkish monetary policy stance relative to rational expectations if inflation is to be stabilized. The required tightening is more severe the larger the inflation exposure, the stickier prices are, and the more risk averse agents are. In other words, a more hawkish stance arises when inflation expectations are not perfectly anchored and the central bank is committed to achieve inflation stabilization—put differently, when agents may have doubts regarding the ability of an inflation targeting central bank to achieve its inflation goal. This drives the central bank to be willing to pay the real cost (in terms of a recession) needed to keep inflation at its desired level to hit the inflation target and avoid losing credibility.

The dynamics of our expanded NK model highlight the role of path dependence and the importance of central bank credibility in the response of the central banks to deviations of expected inflation from target. To test for the salience of the ingredients in our model we estimate a standard open economy Taylor rule in a panel setting and examine whether central banks in countries with a notable history of high inflation react more strongly (i.e., more hawkishly) to deviations from the inflation target.

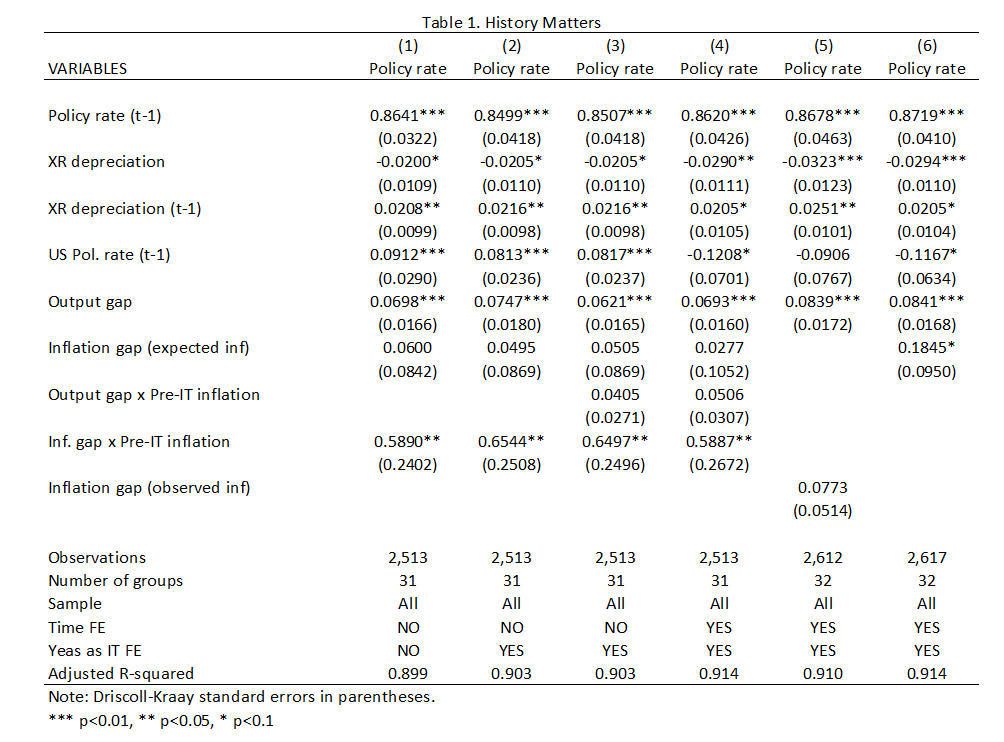

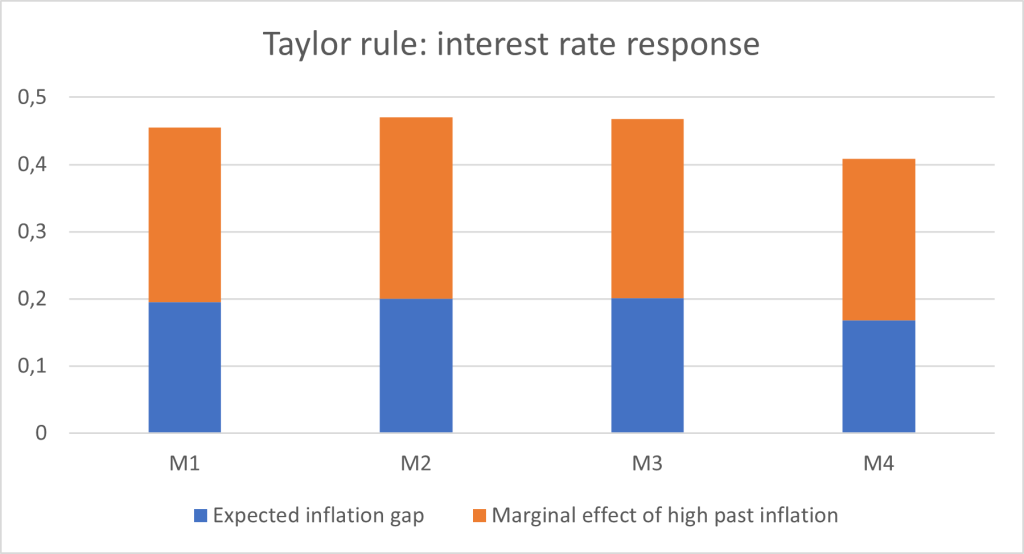

We find that countries that have an inflationary past exhibit larger (and statistically significant) policy rate responses to deviations in expected inflation relative to the target compared to countries that did not suffer high past inflation (Table 1). The estimated elasticity of the policy interest rate to inflation gap shocks in countries with an inflationary past is more than double of those that did not experience high inflation in their past. The estimates are statistically and economically significant, as countries with a high inflationary past change their interest rates by an additional 26 basis point—such that the overall effect is close to 50 basis points. Thus, conditional on its credibility, the average central banker in a country with high past inflation aims at keeping inflation expectations anchored, even if, as discussed above, that may imply a short-run economic activity cost, in order to gain the longer-term benefits of preserving inflation expectations anchored. We also highlight the preponderant weight that central banks put on anchoring inflation expectations when setting interest rates by showing that inflation targeting central banks display a stronger response to deviations of inflation expectations from target than to deviations of observed inflation (in line with received theory, e.g., Svenson, 1997), as can be seen by comparing columns (1) and (2).

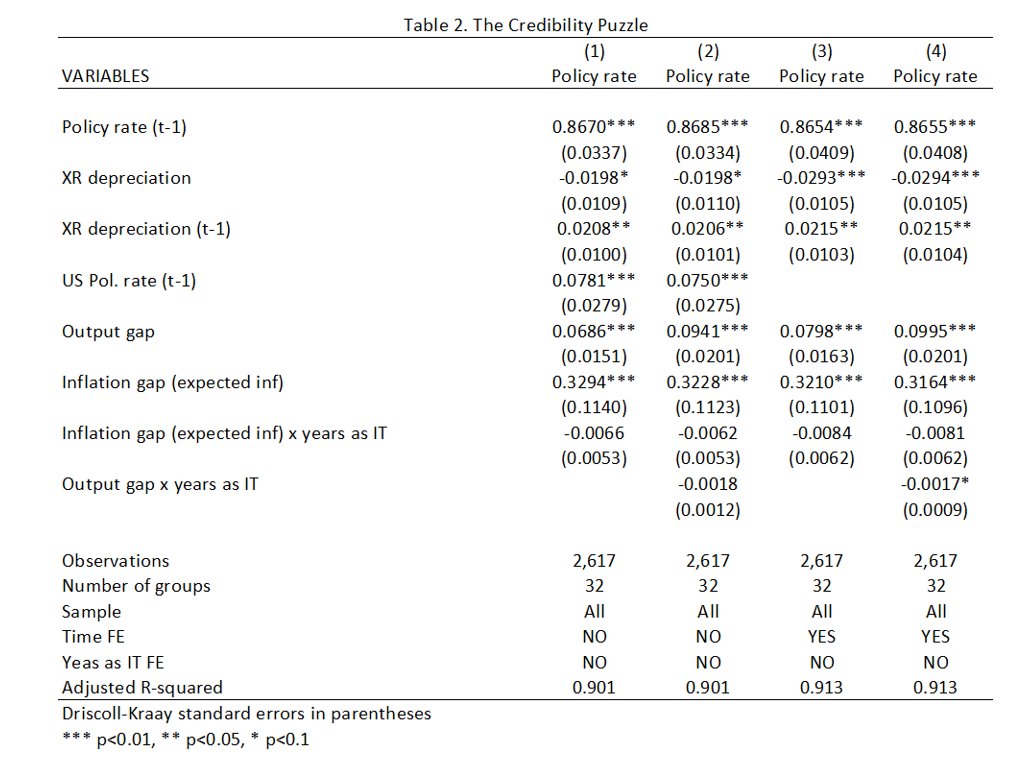

We also explore the stability of the inflation gap and output gap coefficients, as one would expect that as central banks build their credibility over time, they would need a smaller change in the policy interest rate for a similar size inflation gap shock. Our results show that the response of the interest rate to the expected inflation gap does not systematically vary over time (Table 2). In fact, a longer track record of consistent inflation targeting does not translate into smaller interest rate movements for similar expected deviation gaps, triggering the existence of what we label the credibility puzzle.

Our paper highlights the importance of having a legacy of high inflation or inflationary memory, which, all else equal, results in a stronger reaction of the central bank—a larger increase in interest rates in response to any movement in the inflation expectations’ gap. What are possible explanations of these results? On the one hand, our results are related to the literature that analyzes the impact on inflation expectations of individuals based on their experience. For example, as in Magud and Pienknagura (2025, forthcoming), who show, using individual-level surveys for a cross-country sample of emerging and advanced economies, that individuals that have been exposed to longer spells of high inflation have stronger aversion to inflation. It also connects, on the policy side, to Malmendier et al. (2021), who show how policymakers in the US who were exposed to higher inflation when they were younger, tend to vote more hawkishly in Federal Reserve’s FOMC meetings. This is also aligned with Rogoff (1985), as it is optimal to have a more inflation-conservative central banker to mitigate inflation. Probably, our findings are a combination of all such explanations, as central banks internalize individuals’ preferences (including a country’s inflationary memory) into a successful monetary policy framework.

In turn, these findings challenge two important tenets of the received wisdom of theoretical models of inflation targeting. One is that the framework behind inflation targeting rests on assuming full credibility. However, full credibility is not supported precisely by the existence of the credibility puzzle. One could argue that longer data series could eventually result in the disappearance of the credibility puzzle. This may well be the case, which calls for a re-estimation of our results in the future. But, anecdotally, the German Bundesbank aversion to inflation as a consequence of Germany’s hyperinflation in the 1920s—and the transfer of it thereafter to the European Central Bank—seems to suggest that the credibility puzzle may outweigh the passing of time, and that the strength of the containment of inflation never dies away.

The other tenet is the assumption of no path dependence. The fact that the inflationary past plays such an important role in the interest rate reaction function of a central bank to current inflation gap shocks speaks to the importance of internalizing past events in theoretical models. Central banking in inflation targeting countries is clearly history-dependent, something that has typically been ignored in most models of inflation targeting. So, even though IT works.