This note is structured as follows: Section 2 sketches the key elements of the EU COM proposal (cf. EU COM, 2023a, p. 4). Section 3 presents our main arguments why it constitutes a costly policy error that will have significant unintended consequences. Section 4 shows that the current regime works well in Austria. Finally, section 5 presents our conclusions and policy recommendations for making the current regime work across the EU.

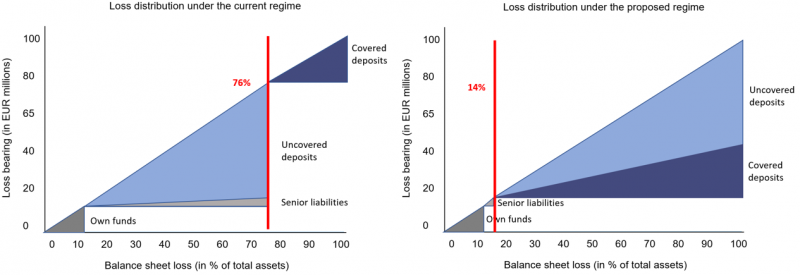

The example shows that, under the proposed regime, uncovered depositors are much less likely to bear losses. This is in line with proposal’s explicit aim of improving depositor protection and protecting depositors from bail-in (EU COM 2023a, pp. 4, 7, 10, 35).10

Despite the higher burden on the DGS, only covered deposits remain the basis for calculating the DGS ex-ante funds, the respective contributions and extraordinary ex-post contributions. This leads to several unintended consequences.

In the following, we look into six unintended consequences of the proposal which are mainly caused – directly or indirectly – by the introduction of the general depositor preference and the ensuing increase in the costs incurred by DGSs.

Banks are likely to pass the higher costs for DGSs on to covered depositors. The volume of, and the contributions to, DGS financing will continue to be only based on covered deposits. This increases the costs of covered deposits for banks, who will pass them on to covered depositors in the form of lower interest rates relative to uncovered depositors. In the end, this shift in the creditor hierarchy constitutes a subsidy from small covered depositors to large uncovered depositors: If a bank fails, large uncovered depositors receive a wealth transfer from the DGS, which will be recouped from banks based on their share in the total of small covered depositors. “The [resolution and DGS] funds come from the banking system and a large part has been paid by [small covered] depositors, as costs like taxes are passed on to customers. Thus, there is a limited difference between bail out by taxpayers and bail out through the deposit insurance fund.” (Berg and Lind, 2023).

The proposal makes it easier to fund DGSs with taxpayer money. Although DGSs and the SRF are primarily financed by bank contributions, public funds still play a critical role.13 The DGS Directive provides for three stages of DGS funding: ex-ante funds, ex-post contributions and alternative funding arrangements (to be repaid by the DGS). However, the current proposal allows directly accessing the third stage of funding, which often involves taxpayer money. Member States have some leeway in implementing this final stage and, thus, its designs vary. Data collected by the EBA show that in nine countries (BE, DK, IE, LV, PL, RO, SE, SI, SK), a credit line (or similar) from the government is the third stage of DGS funding. In the remaining Member States, the funds are provided by a credit line from member banks, the central bank or other banks. Furthermore, funding via the SRF also builds on public funds. If the SRF is depleted, the ESM acts as a backstop and lends the necessary funds to the SRF to finance a resolution. The more frequent use of DGSs and their higher losses make recourse to taxpayer money more likely.

More banks must be treated as systemic in going concern. The US regional bank crisis demonstrated that ex-ante crisis prevention needs to be consistent with ex-post crisis management (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2023). The Capital Requirements Directive (CRD) stipulates that if a bank’s failure poses a risk to financial stability and the real economy, macroprudential supervision shall activate higher macroprudential capital buffers and tighter supervision.14 Similarly, resolution authorities shall impose higher MREL requirements for systemic banks to ensure that they are resolvable without government support. More smaller banks would have to hold MREL and would be required to prepare resolution plans to avoid the need for DGS funds in the case of insolvency. While this would improve their resolvability, it is inconsistent with the EU COM’s motivation for its proposal, i.e., the fact that some banks “cannot” issue MREL for “structural” reasons.

The proposal increases the accessibility of the SRF. Under the current regime, the political costs for the NRAs of gaining access to the SRF are the bail-in of at least 8% of bank shareholders and creditors, mostly in the respective Member State where the failing bank is resident. This price can turn out to be high.15 However, this provision is a feature of the BRRD and the Single Resolution Mechanism Regulation (SRMR), not a bug. The hurdle is to ensure that the national authorities cannot shift the costs of their failures – e.g., lax supervision, forbearance, insufficient resolvability – to the euro area level. In comparison, the political costs of bailing in DGSs are much lower. In sum, the proposal makes it easier for NRAs – even incentivizes them – to shift some of the costs of bank failures to the European level. Easier access to the SRF increases the likelihood of burden sharing between weaker and stronger banking systems. Hence, the proposal can be seen as a first step towards EDIS through the backdoor.

Yet, a general depositor preference will not increase depositor confidence when a bank is about to fail. Formerly, the NRA decides whether to exempt uncovered deposits from bail-in only after the FOLTF decision. Hence, even though it is highly likely that their deposits are exempt from bail-in, uncovered depositors still have an incentive to withdraw their deposits even under a general depositor preference. Furthermore, the potential exemption of all deposits from bail-in leads to confusion among investors as to whether EU banks effectively have enough MREL and who must bear what share of the burden in resolution. This increases the costs of other MREL in going concern and, hence, increases the credit costs for the real economy, especially for households and SMEs. As a minimum, all deposits that can be excluded from bail-in must also be excluded from MREL.

The better protection of large uncovered deposits makes these highly runnable deposits even more attractive19 relative to financial market products (such as commercial paper), ceteris paribus. The latter expose investors to funding liquidity risk, interest rate risk and market liquidity risk. In contrast, uncovered bank deposits benefit from a free implicit insurance against all these via a better protection against counterparty risk. This contradicts key objectives of the CMU, in particular the promotion of market-based financing and access to alternative providers of funding beyond banks for non-financial corporations.

The Austrian banking system absorbed the costs of four market exits via DGSs during the Covid-19 crisis and the energy crisis after the start of the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine without causing negative repercussions for financial stability, depositor confidence or the real economy.26 Hence, for small and medium-sized banks, market exits via the insolvency regime can work well (i) where efficient DGS funding strategies and super-priority of covered deposits lead to fast recoveries of DGS payouts and (ii) where authorities adopt sound macroprudential strategies to make the current CMDI framework work.

See, for example, NORD/LB (2019), Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena (2017), Banca Carige (2019), Banca Popolare di Vicenza (2017), Veneto Banca (2017), National Bank of Greece (2015), Piraeus Bank (2015), Banco Internacional do Funchal (2015) (EU COM 2023d).

The package includes amendments to the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) (EU COM, 2023a) the Deposit Guarantee Schemes Directive (DGSD) (EU COM, 2023b) and the Single Resolution Mechanism Regulation (SRMR) (EU COM, 2023c). The package published by the Commission also contains a Communication on the review of the crisis management and deposit insurance framework contributing to completing the banking union, including a call to resume discussions on establishing a European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS).

Preventive measures aim at preventing the failure of a credit institution and may be activated only if certain conditions apply, such as, in particular, the costs of the measures do not exceed the costs of fulfilling the statutory or contractual mandate of the DGS (Article 11(3)(c)DGSD); alternative measures intend to preserve the access of depositors to covered deposits, including the transfer of assets and liabilities and deposit book transfer, in the context of insolvency, and can be taken provided that the costs borne by the DGS do not exceed the net amount of compensating covered depositors at the credit institution concerned (Article 11(6) DGSD).

For further information on the motivation for the proposal see also European Banking Authority (EBA) (2021).

For example, uncovered deposits remain MREL-eligible but the objective is not to bail them in; banks should have enough MREL such that there is no need to bail them in, but the proposal is motivated by the observation that some banks cannot have sufficient MREL for structural reasons. Banks transfer the contributions to the DGSs, but given the low price elasticity of covered deposits, it is likely that these costs are passed on to covered depositors.

The impact assessment lists 27 cases of application of the CMDI framework since 2015, of which 10 received public support. Out of the 27 cases, (i) 11 banks went into resolution, and in one case, public funds were injected to support resolution; (ii) in 6 cases (4 in Italy and 2 in Greece), authorities implemented precautionary public measures based on public funds; (iii) in 6 cases (4 in Italy and 2 in Latvia), the banks were subject to national insolvency proceedings, (of which 2 cases required public support and 2 were supported by the DGS, while the 2 cases in Latvia did not receive external support); (iv) in 4 cases (3 banks in Italy including 1 that required preventive measures twice and 1 in Germany) banks were subject to preventive measures which were funded by the DGS (Italy) or the state (Germany). Some banks underwent more than one treatment with, first, preventive measures or precautionary measures and, then, another round of preventive measures and/ or insolvency (EU COM 2023d, Annex 9, pp. 349).

See Autonomous, 2023.

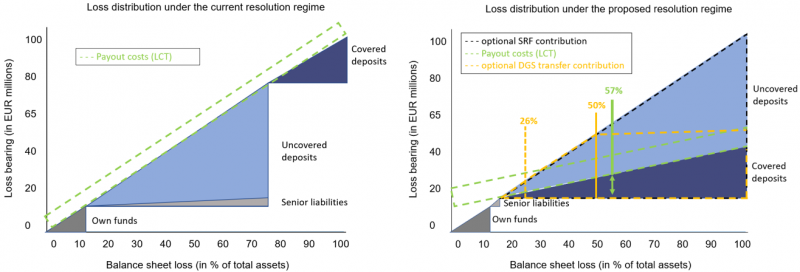

Assuming that payout costs are constant and amount to 50% of covered deposits. For illustration, under the general depositor preference full recovery might take 10 years, with opportunity costs of 4% p.a. and adding 2% administrative costs yields costs of EUR 12 million for the DGS for a payout of EUR 24 million. In some Member States, the costs of payouts might already be high without general depositor preference, due to inefficient insolvency procedures and DGS funding arrangements.

The assumption does not hold for Austria, where the discount of bank loans in insolvency was roughly 20%, similar to the discounts in purchase and assumption transactions under the FDIC resolution procedures (see Bennet and Unal, 2015; and FDIC, 2017).

For the deposits that are not covered, this approach facilitates their protection where it is necessary for safeguarding financial stability and depositor confidence.” (EU COM, 2023a, Recital 40). These conditions are not specified in any detail.

Data source: ECB Statistical Data Warehouse. However, the increase by 275% is only an indicative order of magnitude. It is difficult to estimate more precisely, as some uncovered deposits are already protected under the current regime (i.e., deposits of other banks with a maturity of less than 7 days, fiduciary deposits).

In Annex 9, p. 349, the impact assessment of the European Commission includes several banks that, first, received preventive support or precautionary recapitalization, and then went into insolvency anyway (EU COM, 2023d, Annex 9, pp. 349).

“Indeed, it is the strength of the backstop that gives a DGS its credibility.” (Huertas, 2022, p. 189).

The EU COM acknowledges this and aims at reducing the cost of failure. It suggests triggering resolution earlier via the introduction of an “early warning period” when there is a material risk that an institution meets the conditions for being assessed as FOLTF, but solutions to prevent a FOLTF are still available. We fully support this part of the proposal, as it reduces the costs of failure and might shift upwards market expectations of bank capital and liquidity requirements.

See the political pressure in the US that led to the “systemic risk exemption” in the case of SVB, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank and the evidence presented for bailouts of subordinated debt in EU COM (2023 d, Annex 9).

See also Calomiris and Kahn (1991), Cebenoyan and Cebenoyan (2008), Alanis et al. (2015), and Balke and Wahrenburg (2019) on the effectiveness of monitoring by (large/informed) uncovered depositors. See Cecchetti et al. (2023) on the social costs of preventing efficient bank runs.

It might also raise the costs for supervisors due to more intrusive supervision, and possibly for banks due to parallel regimes of DGS, competent authorities and resolution authorities.

Stiglitz (1992) argues that [d]eposit insurance results in a process of Gresham’s law: “Depositors have no incentive to look to what the S&L does with their money. Financial institutions which engage in riskier investments can offer higher returns, and only these promised returns matter to the depositors.” Greenbaum and Thakor (1997, p. 486) present evidence based on the option feature approach to deposit insurance that it indeed leads to higher risk taking.

It is likely that the general depositor protection will reduce interest rates on uncovered deposits somewhat .via a reduction of the risk premium relative to covered deposits, as the exemption form bail-in is uncertain. Danisewicz et al. (2018, p. 4493) document that “…depositor preference laws that confer priority on depositors reduce deposit rates.”). But given the implicit subsidy of uncovered deposits such a decrease in the interest rate is unlikely to fully compensate for their better protection.

See Schmitz and Eidenberger (2021).

Based on the Austrian experience (full recovery of the DGS payouts within one year), discounting recoveries by 4% and adding 2% handling costs.

From 2020 to 2022, the Austrian DGS ESA successfully handled four payouts: https://www.einlagensicherung.at/de/cases.php.

See Hardy (2014). He also points out that the pricing of the protection must be risk-sensitive; “…the probability of distress might not be reduced if those that benefit from collateralization demand an interest rate that ignores the reduction in LGD that collateralization should achieve.” (p. 111). Unfortunately, this is not the case in the CMDI proposal: Uncovered depositors would enjoy better protection, but the costs thereof would still be passed through to covered depositors via banks’ contributions to the DGSs. The latter are based solely on the banks’ shares of covered deposits in the system and ignore their funding via uncovered deposits.

See EU COM (2013) Recital 90.

See EU COM (2014) Article 31 2 (b) and (c).

The four Austrian cases are not included in the European Commission’s impact assessment (EU COM, 2023d), which argues that, in several cases, uncovered depositor losses in resolution have led to a loss of depositor confidence (EU COM, 2023d, Annex 8, pp. 315). However, most of the cases date back to the time before the BRRD was introduced and/or to cases associated with a sovereign debt crisis (e.g., Northern Rock in 2007, Iceland in 2008, Greece in 2012, Cyprus in 2013). Only one case involved a resolution under the BRRD, namely the resolution of Andelskassen JAK Slagelse, and the EU COM concludes that the bail-in of uncovered depositors worked “…without observed loss of depositor confidence.” (EU COM, 2023d, Annex 8, p. 320).