This policy brief is based on ’The effects of monetary policy on banks and non-banks in times of stress’ by Anisa Tiza Mimun, Gàbor Fukker and Matthias Sydow, ECB Working Paper No 3114. The views expressed here are those of the authors of the original paper and do not necessarily represent the European Central Bank.

Abstract

This study investigates the effects of monetary policy on banks and non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), with particular attention to the role of financial stress. We use high-frequency identified monetary policy shocks and state-dependent local projections to capture non-linear responses of banks and non-banks for different states of financial stress. Drawing on aggregated balance sheet data, including total assets, debt securities, and loans, we find that monetary tightening leads to overall contractions in total assets and debt securities’ holdings, with particularly pronounced effects for banks and investment funds. Loan responses are also heterogeneous, with investment funds and money market funds showing a delayed but gradual increase in lending. Importantly, we find that financial stress significantly amplifies the effects of monetary policy across all sectors and asset classes. Our results highlight the differentiated roles of financial intermediaries in the transmission of monetary policy and underline the importance of financial conditions in determining its overall effectiveness.

The impact of monetary policy on the banking sector has been extensively examined in the literature (e.g., Kashyap and Stein, 2000; Kashyap et al., 2002; Ehrmann et al. 2002; Altunbas et al. 2009). Empirical evidence broadly supports the view that tighter monetary policy conditions adversely affect lending behavior and credit supply within the banking system.

However, comparatively less attention has been devoted to understanding how monetary policy influences the broader financial system, i.e. the non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI) sector, which includes investment funds, money market funds, insurance companies, and pension funds.

Our work aims to contribute to this research gap by offering an analysis of the different responses of banks and non-banks to monetary policy shocks. We argue that this analysis is not only of academic interest but also of considerable practical importance for policymakers and supervisory authorities. Moreover, by including different levels of financial stress into our analysis, we aim to understand in depth the role of financial market conditions in influencing the transmission of monetary policy. Our central hypothesis is that the effects of monetary policy are likely heterogeneous across financial sectors, particularly in times of high(er) financial stress. For example, in the case of investment funds, an accommodative monetary policy stance is generally associated with an expansion in total assets, both in terms of valuation and transaction volumes. However, during periods of heightened financial stress, investor behaviour may shift in line with flight-to-safety dynamics, which may, in turn, lead to a reallocation of funds towards safer asset classes, such as bond funds, or even a retreat to the relative security of bank deposits.

For our analysis, we consider the whole financial sector in the euro area, and hence, include banks and non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs). The latter includes investment funds (IF), money market funds (MMF), pension funds (PF), and insurance companies (IC).1

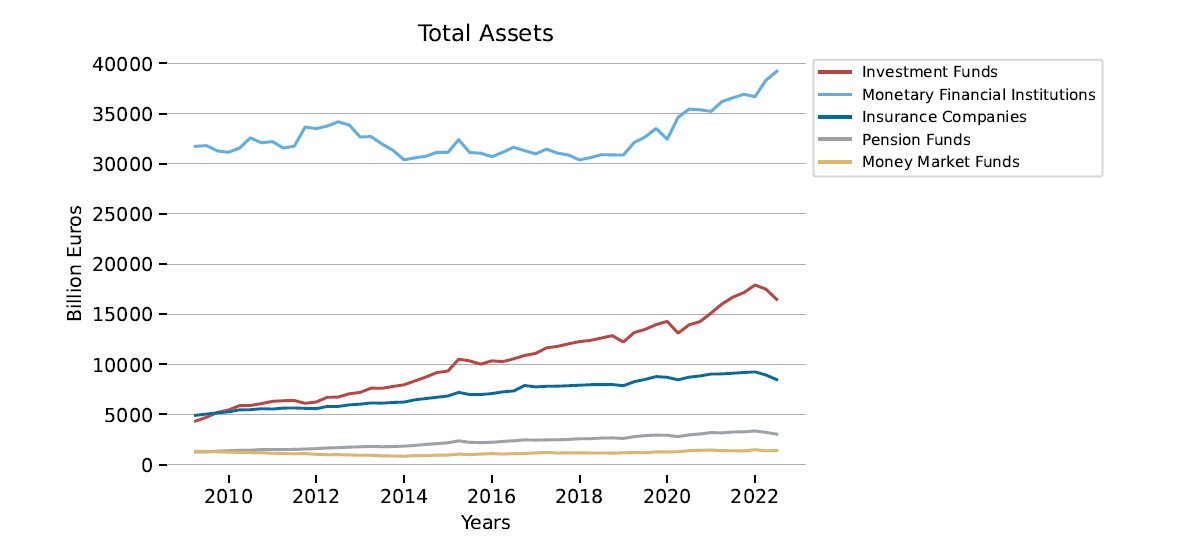

Figure 1. Total assets of banks and non-banks

Figure 1 shows the total assets of banks and non-bank entities. The data indicate a continuous increase in total assets over the period, with banks holding the largest share. Investment funds also show a substantial rise in total assets, particularly after 2015. Pension funds, insurance companies, and money market funds display comparatively lower asset volumes, with minor fluctuations observed over time.

For our analysis, we employ the local projection approach introduced by Jordà (2005) and identify monetary policy shocks using high-frequency event-based measures that capture unexpected changes in asset yields around ECB press conferences introduced by Altavilla et al. (2019). A state-dependent framework in the spirit of Tenreyro and Thwaites (2016) is additionally implemented to account for differences in the transmission of monetary policy across periods of financial stress and calm times, as proxied by the CISS index. Further, financial stress is chosen as the main state variable for several reasons. First, monetary policy transmission is likely to differ under high financial stress, as investors exhibit flight-to-safety behaviour, reallocating assets or increasing bank deposits. Second, since the CISS index captures systemic risk and volatility across the euro area’s financial system, it serves as an appropriate measure for studying heterogeneous monetary policy effects and potential sources of financial instability.

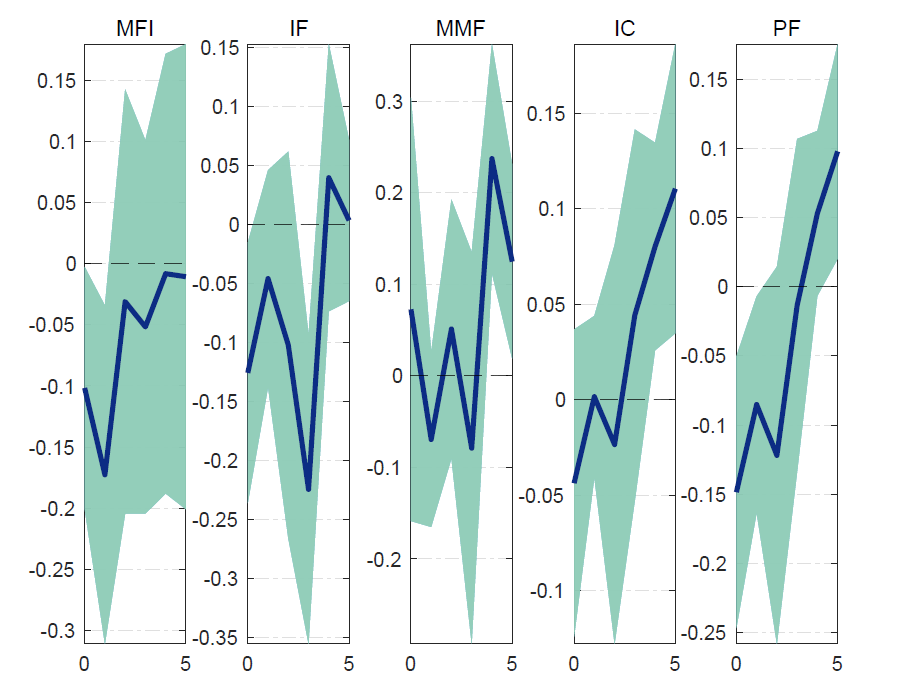

Our findings include results from a baseline estimation in which we only consider the responses of banks and non-banks to a monetary policy shock. Further, in a state-dependent approach, we include two different states of financial stress, i.e. high vs. low financial stress, into our estimation.2 Regarding our baseline estimation for total assets (Fig. 2), banks, investment funds, insurance companies and pension funds display similar negative responses. The response paths of insurance companies and pension funds are closely aligned, suggesting comparable portfolio structures or strategic behaviour. By contrast, banks and investment funds both react negatively on impact, but their longer-term trajectories diverge, reflecting potential differences in business models or regulatory frameworks.

Figure 2. Impulse response functions of total assets3

Turning to debt securities (Fig. 3), the responses of banks and non-banks are uniformly negative following a tightening shock, with the only exception of money market funds. The decline is similar across banks, investment funds, insurance companies, and pension funds, indicating that all sectors are sensitive to higher interest rates. The similar magnitudes and patterns suggest a common mechanism, likely a contraction in valuation or issuance of debt instruments under tighter monetary conditions. On the other hand, money market funds display a relatively strong and significant increase in their debt securities’ holdings.

Figure 3. Impulse response functions of debt securities

Finally, in the case of loans (Fig. 4), banks exhibit the expected negative impact response, consistent with higher borrowing costs and reduced credit supply. Investment funds and money market funds also react negatively on impact but subsequently expand their lending, with money market funds showing a pronounced and persistent increase. These dynamics serve as an indication for a potential reallocation of credit provision from traditional banks towards non-banks as monetary policy tightens.

Figure 4. Impulse response functions of loans

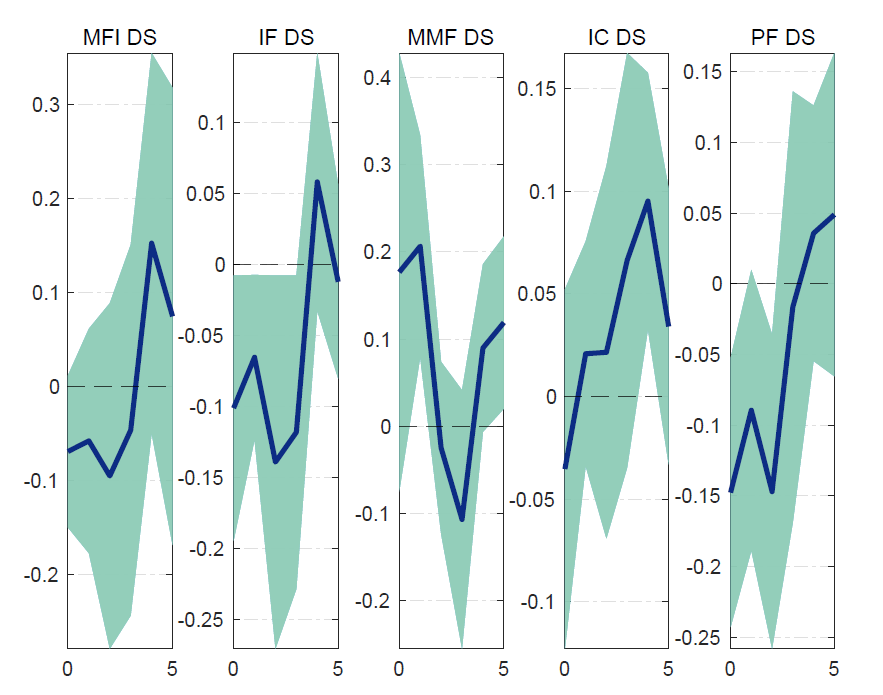

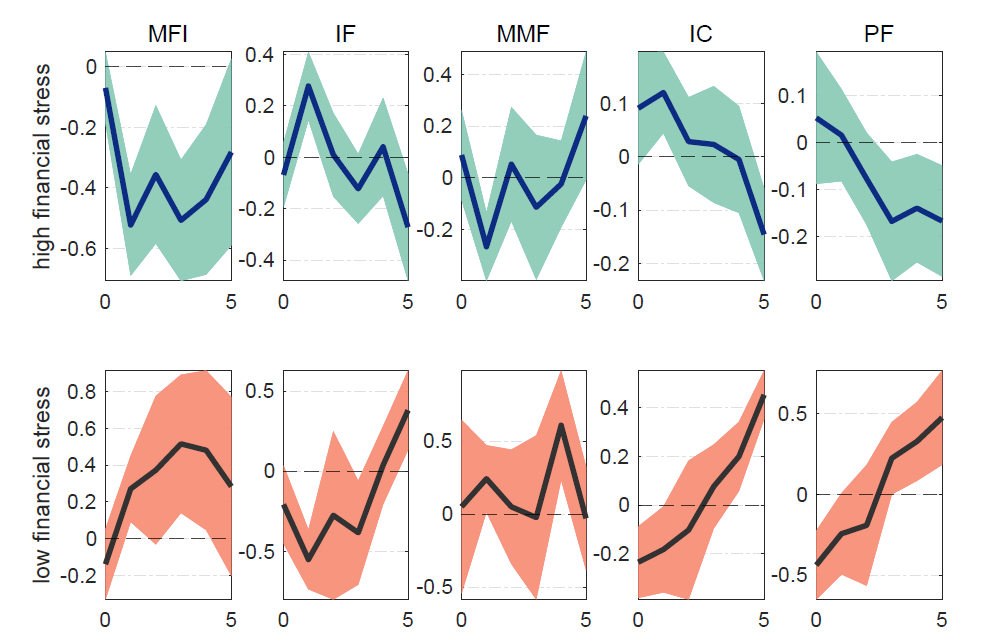

Turning to our state-dependent analysis for total assets (Fig. 5), banks exhibit a sharp decline on impact in periods of high financial stress, highlighting their vulnerability to tighter monetary conditions when markets are strained. In contrast, investment funds respond in the opposite direction, suggesting an ability to adapt or capitalize on turbulent conditions. Insurance companies and pension funds also experience declining total assets under high stress, reflecting their exposure to adverse market dynamics.

Figure 5. Impulse response functions of total assets in high financial stress and low financial stress states

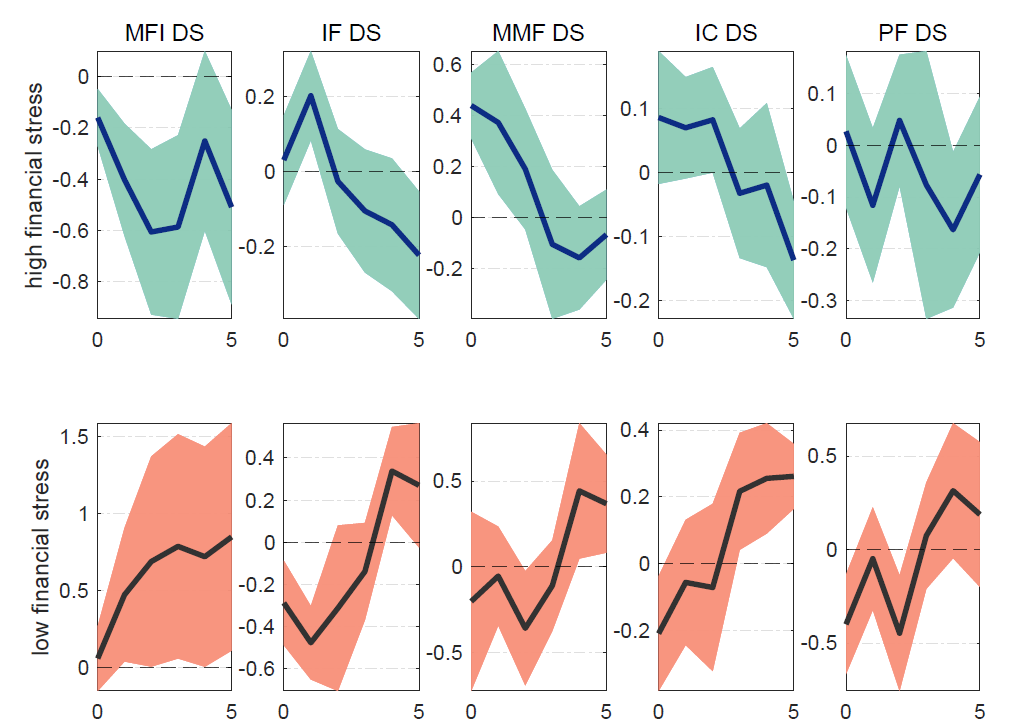

Turning to debt securities (Fig. 6), banks show a consistent negative response to monetary tightening during high-stress periods, with values continuing to fall over several quarters. Investment funds, by contrast, react positively under high stress, an indication that stress amplifies their responsiveness and may shift their investment behaviour toward debt instruments. Money market funds display the strongest positive impact response in times of stress, consistent with a temporary preference for short-term safe assets, though their response weakens over time. Insurance companies and pension funds remain largely unresponsive under stress.

Figure 6. Impulse response functions of debt securities in high financial stress and low financial stress states

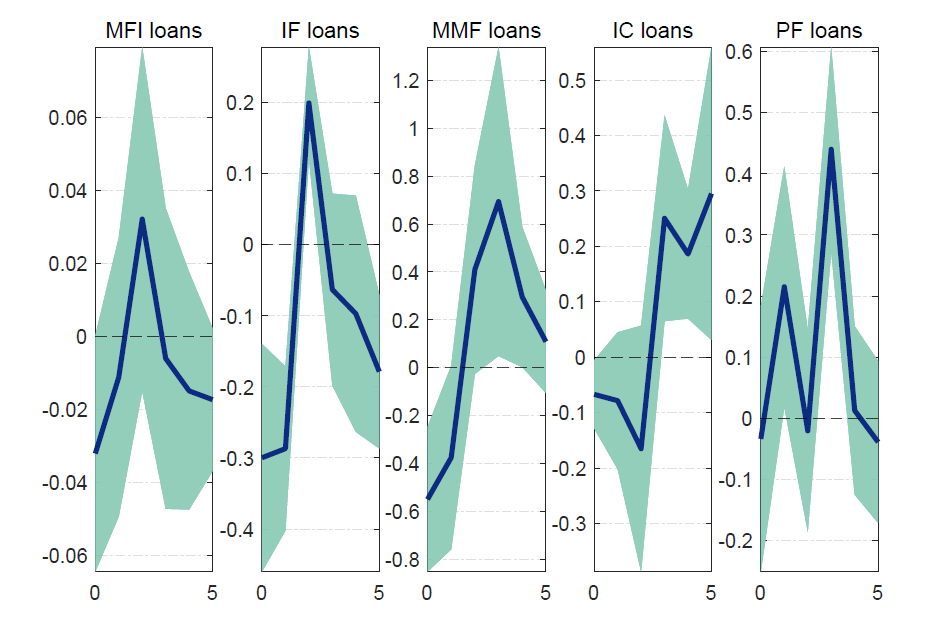

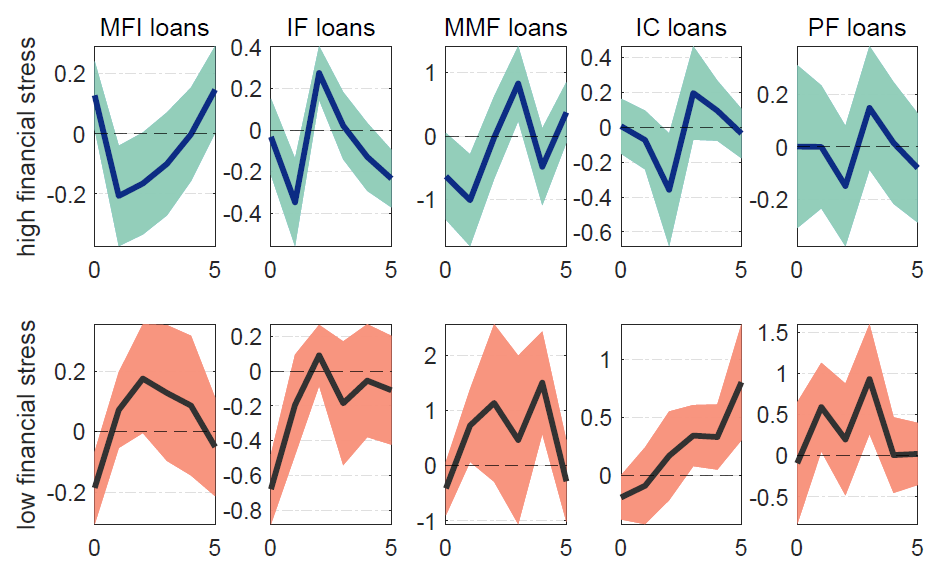

Regarding loans (Fig. 7), banks’ lending declines as expected following a tightening shock. Money market funds and investment funds also contract strongly on impact but gradually expand their lending activity afterward, particularly in later quarters. This dynamic implies that non-bank financial intermediaries may partially offset banks’ retrenchment during stressed periods by supplying short-term or opportunistic credit. Insurance companies and pension funds again show muted responses under high stress, while in calmer environments, insurance companies’ lending decreases initially but subsequently increases, reflecting a delayed but notable adjustment to changing monetary conditions.

Figure 7. Impulse response functions of loans in high financial stress and low financial stress states

This study investigates how monetary policy affects the balance sheets of banks and non-banks, focusing on aggregated balance sheet positions such as total assets, debt securities, and loans. The analysis covers banks, investment funds, money market funds, insurance companies, and pension funds, with particular attention to how financial stress shapes these dynamics. Our results show that the impact of monetary policy depends strongly on the prevailing level of financial stress. In periods of high financial stress, monetary tightening leads to substantial differences across financial sectors. Banks experience a sharp decline in total assets, debt securities, and loans, indicating that they are highly vulnerable to tighter monetary conditions. In contrast, investment funds react in the opposite direction, however with a delay, expanding their assets and debt securities, which suggests that they can adapt more flexibly or even benefit from changing conditions when stress is elevated. Their lending activity, after an initial strong decline, also increases gradually in times of stress. Insurance companies and pension funds show moderate declines in assets during high stress, reflecting their sensitivity to adverse market conditions but also their relatively stable nature compared to banks. Further, money market funds initially increase their holdings of debt securities but reduce them over time, pointing to a short-term shift toward safer, liquid assets. Regarding their lending behaviour, the results indicate that after a strong initial decline, money market funds gradually increase their lending activities in a high-stress environment. Overall, our findings underline the importance of accounting for financial stress in the transmission of monetary policy.

C. Altavilla, L. Brugnolini, R. Gürkaynak, R. Motto, and G. Ragusa. Measuring euro area monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 108:162–179, 2019.

Y. Altunbas, L. Gambacorta, and D. Marquez-Ibanez. Securitisation and the bank lending channel. European Economic Review, 53(8):996–1009, November 2009.

M. Ehrmann, L. Gambacorta, J. Martínez Pagés, P. Sevestre, and A. Worms. Financial systems and the role of banks in monetary policy transmission in the euro area. Technical report, 2002. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=356660 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.356660.

Ò. Jordà. Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. American Economic Review, 95(1):161–182, 2005.

A. Kashyap and J. Stein. What do a million observations on banks say about the transmission of monetary policy? American Economic Review, 90(3):407–428, 2000.

A. Kashyap, Rajan, R., Stein, J. C. Banks as Liquidity Providers: An Explanation for the Coexistence of Lending and Deposit-taking, Journal of Finance, American Finance Association, vol. 57(1), p. 33-73, 2002.

Silvana Tenreyro and Gregory Thwaites. Pushing on a string: Us monetary policy is less powerful in recessions. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 8 (4):43–74, 2016.

Due to data availability issues, we exclude other financial intermediaries (OFIs).

In our working paper, we provide all detailed impulse response functions. For example, we also study the interconnections between banks and non-banks, i.e. the banks’ holdings of different non-bank shares and vice versa.

For all our impulse response functions, we display the estimated response within a 68% confidence bands to a 1pp monetary policy shock. X-axis displays quarters, y-axis represents percentages.