In a globalised and digitalised economy, the mobility of capital and labour is increasing. This promotes global tax competition: in the case of corporate income taxation, a race to the bottom can still be observed today. Contrary to this trend, the effective average tax burden of a highly qualified employee (net income 100,000 euros) has noticeably been stagnating, while top statutory tax rates for high-income earners have been rising. The developments of the last decades and the large regional dispersion in effective tax burdens put Central and Western EU Member States under high competitive pressure. However, the agreement on a global minimum taxation can set a new lower bound to the corporate race to the bottom. In the future, taxation of highly qualified, mobile workers could become more important due to the massive digitalisation boost caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

The reduction of trade barriers and the increase in capital mobility accompanying globalisation have led to a wide range of location opportunities for business investment in a globally integrated market. It is well known that taxation can play a central role in the location decision of multinational companies, alongside various non-tax factors such as production costs or market potential. Unlike these other location factors, taxes can be visibly influenced by governments. Thus, it is not surprising that countries have participated in the “race to the bottom” by continuously reducing statutory corporate tax rates over the past decades.

Concurrently, the ongoing transition to a knowledge-based economy and the fast digitalisation is increasing the transmission of ideas and meanings through labour mobility. This transition is not only leading to an increased shift in economic activity from manufacturing to services but is also changing the characteristics of the workforce. In particular, the rising digital transformation of corporations and working conditions, such as remote working, increases demand and therefore intensifies the competition for internationally mobile, highly educated employees. This can enable highly skilled employees to shift a greater portion of non-wage labour costs – at least to some extent – to the employing multinational enterprises.

Consequently, the latter are not only confronted with the direct costs of corporate taxation but also with the economic consequences of the shifted incidence of labour taxation. Hence, the synthesis of corporate and labour taxation will be increasingly important for corporations’ location decisions in the near future and thus for the location attractiveness of countries, especially in an integrated region like the European Union. This expertise sheds light on the tax attractiveness of a location for internationally operating countries from both the perspective of corporate income taxes and the tax conditions for highly qualified employees in 26 OECD countries from 2009 to 2019.

To identify trends in countries’ location attractiveness from a tax perspective for corporations and highly skilled employees over the last decade, well-established effective tax burden measures developed by Devereux and Griffith (1999; 2003; for corporate taxation) and Elschner and Schwager (2005; 2007; for labour taxation) are used. In particular, the measurement of the tax location attractiveness is based on effective average tax rates (EATR) for both corporations and highly skilled employees.

Effective tax rates should be preferred over statutory tax rates. They incorporate the most significant features of the underlying corporate and personal income tax system and are directly comparable due to their aggregated level in relation to different locations. In the context of corporate taxes, it is assumed that an investor will choose the location for which the net present value of the investment is least reduced by taxation, that is, where the EATR is lowest. In the context of highly skilled employees, the EATR expresses how much the employer must expend in addition to a predetermined disposable income due to taxation. In other words, the lower the EATR, the more attractive a country is for companies employing highly skilled employees.

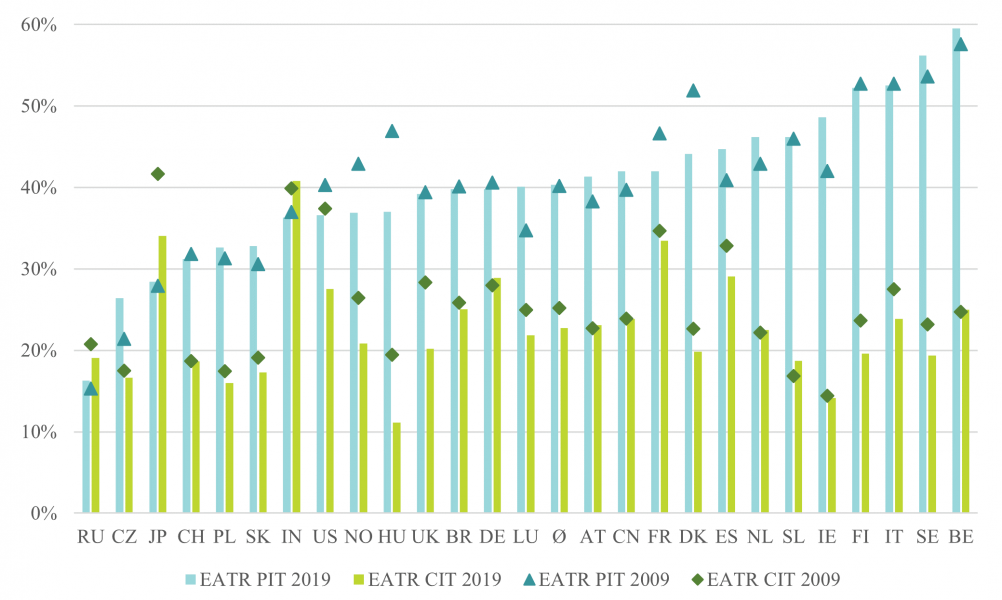

Figure 1 depicts the effective average tax rate on corporations and highly skilled labour for the countries considered in 2009 and 2019. A remarkable dispersion in corporate tax burdens that persists over time can be observed. In 2009, the EATR ranged from 14.4 per cent in Ireland to 41.7 per cent in Japan, while in 2019, Hungary showed the lowest EATR with 11.1 per cent and India the highest with 40.8 per cent. Focusing on the considered EU Member States, corporate taxpayers in the Eastern European countries clearly face the lowest tax burdens. In contrast, in France, for example, companies’ effective average tax burden amounts to 34.7 per cent – the highest value in Europe in 2019. In comparison, Germany ranks third among the EU Member States considered with almost 29 per cent.

In line with previous studies, a declining trend in effective average tax rates on corporations in the EU can be confirmed. However, this downward trend and the accompanying tax competition for corporate investments lost pace and slowed down over the last decade. In contrast, for the transition economies Brazil, China, India and Russia, the aforementioned trend cannot be confirmed as effective corporate tax burdens stayed (almost) constant over the observation period.

Figure 1: Development of effective tax burdens on corporations and highly skilled employees between

2009 & 2019

Source: based on Fischer et al. (forthcoming)

Besides corporate taxation, tax incentives have also been shown to influence domestic and cross-border migration of highly skilled workers. Countries that impose above-average taxes on highly skilled workers might become less attractive as an employment location for multinational enterprises. These differences can be immense, using the example of an unmarried, childless employee who has a disposable income of 100,000 euros after taxes and duties: In 2019, Russia levied an effective average tax rate on highly skilled employees of 16.3 per cent, while this was 59.5 per cent in Belgium. In other words, employers in Russia had to pay 119,474 euros in 2019, while Belgian employers paid 246,914 euros – more than double – to provide the same disposable income.

A closer look at the considered EU Member States shows that Eastern European countries are among the most attractive countries for employing highly skilled employees from a tax perspective. The Northern, Central and Western European countries, on the other hand, show an above-average level of the effective tax burden, on average, which has even slightly increased over the last decade. While Germany is one of the least attractive EU Member States from a corporate income tax perspective, it is the most attractive for employing highly skilled employees among large EU economies.

In contrast to the previous results on corporate income taxation, no clear down- or upward trend in effective tax burdens emerged. Thus, the average effective tax burden on highly skilled employees remained relatively constant in recent years.

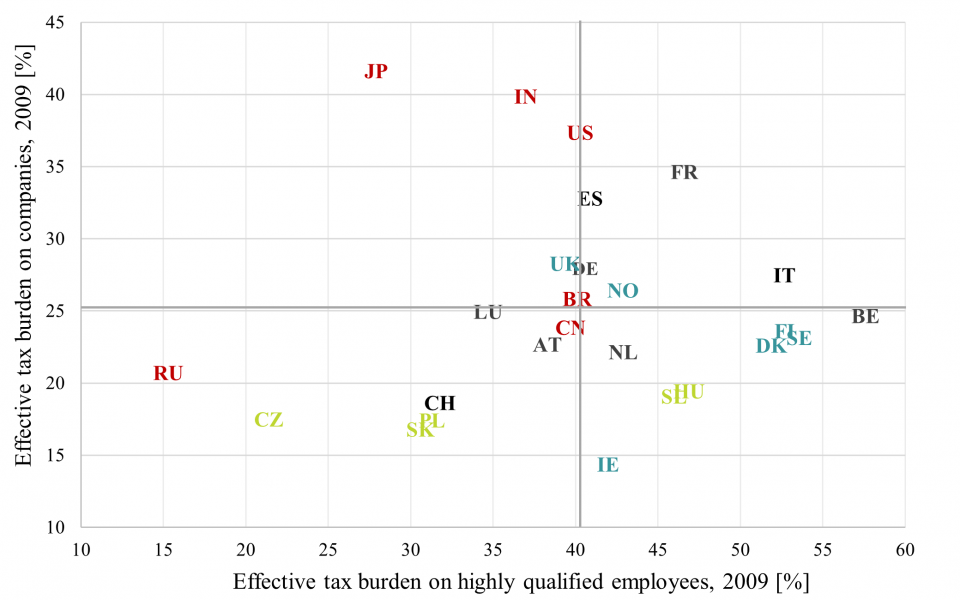

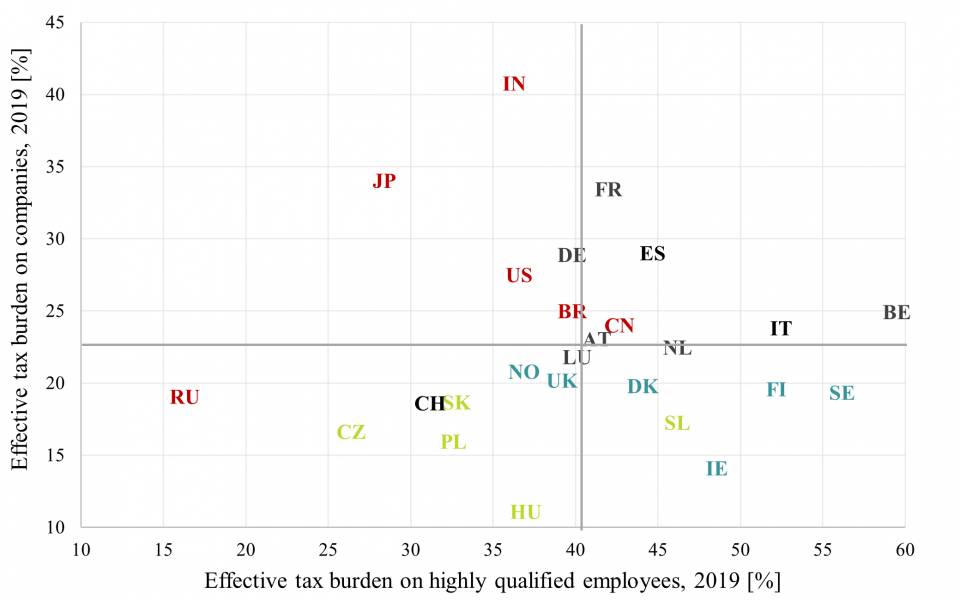

To determine the overall attractiveness of countries from a tax perspective and their scope for future tax competition, both indicators – effective average tax burden on companies and highly qualified employees – are combined and graphically illustrated in Figure 2. Both indicators show remarkable differences between the countries considered. These regional differences have the potential to influence significantly the geographical distribution of (innovative) companies and highly skilled labour, especially in an integrated region like the European Union.

Figure 2: Correlation of tax burdens on corporations and highly skilled employees in 2009 & 2019

Source: based on Fischer et al. (forthcoming)

Considering both indicators together, four tax strategies can be identified among the 26 OECD countries considered: The Eastern European countries (green) – except for Slovenia – tend to pursue a traditional low-tax policy. Russia and Switzerland also fall into this category. The majority of Central and Western European countries (black), on the other hand, levy an above-average effective tax burden on companies and highly skilled employees. The Northern European countries (blue) under consideration, as well as Ireland and Slovenia, are characterised by a below-average effective tax burden on mobile capital income, while highly qualified labour is taxed at an above-average rate there. In the fourth strategy, pursued mainly by non-European countries (red), i.e., India, Japan and the USA, the tax burden is reversed: Corporations are taxed above average and highly qualified workers below average.

These quantifications give a first impression of the development of international tax competition for corporations and highly skilled employees over the last decade, especially within the European Union. Central and Western EU Member States are increasingly under pressure. In order not to lose their attractiveness, countries like France, Italy and Germany in particular need to reduce the tax burden. Germany has failed to implement major corporate tax reforms in recent years and has thus become less appealing for investments in capital and labour.

It remains to be seen whether the race to the bottom in corporate income taxation will continue. In any case, the pandemic-induced budget gaps make this scenario less likely. Furthermore, it is still unclear to what extent the global minimum tax rate of 15 per cent recently adopted by OECD countries will reduce tax competition on corporate investments. Against the background of increasing restrictions on corporate tax planning and the transition to a knowledge-based economy, the taxation of labour could become even more important in terms of tax competition in the future. Already today, some EU countries, especially those with above-average tax rates for employees, offer tax incentives for highly qualified foreign workers to become more attractive in the competition for internationally mobile specialists and management staff. However, providing such incentives may further increase tax competition between EU countries.

Devereux, M. P., and Griffith, R. (1999). The taxation of discrete investment choices. Institute for Fiscal Studies Working Paper, 98/16 (Revision 3). http://www.ifs.org.uk/wps/wp9816.pdf

Devereux, M. P., and Griffith, R. (2003). Evaluating Tax Policy for Location Decisions. International Tax and Public Finance, 10, 107–126.

Elschner, C., and Schwager, R. (2005). The Effective Tax Burden on Highly Qualified Employees – An International Comparison (1st ed.). Physica-Verlag.

Elschner, C., and Schwager, R. (2007). A Simulation Method to Measure the Effective Tax Rate on Highly Skilled Labor. FinanzArchiv / Public Finance Analysis, 63(4), 563–582.

Fischer, L., Heckemeyer, J. H., Spengel, C., and Steinbrenner, D. (forthcoming). Tax policies in a transition to a knowledge-based economy – The effective tax burden of companies and highly skilled labour. Intertax. (An earlier version of the study can be downloaded at: www.zew.de/PU83087-1)