The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Central Bank, the Eurosystem or the Bank of Finland. The authors wish to thank Luis Morais, George Pennacchi, Nicolas Véron and Hanna Westman for their valuable comments and suggestions. Any errors remaining are solely those of the authors.

Events in 2023 in the US and Swiss banking sectors have once again brought the stability of the financial system under scrutiny. We discuss some of the lessons that can be learnt from them, particularly with an eye to the further strengthening of the European banking union. Although certain regulatory and supervisory shortcomings may have contributed to the events referred to, crisis resolution worked relatively swiftly. Arguably, having a unitary authority responsible for both resolution and deposit insurance, such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in the United States, is a crucial factor behind successful resolution. Similarly, it can be argued that a major improvement for the European banking union would be to bring bank resolution and deposit insurance under the same roof, a task that could be naturally entrusted to the Single Resolution Board (SRB). Importantly, this would require completion of the common European deposit insurance scheme, the EDIS, which, as a practical first step, could be best implemented by including only the significant institutions which are directly under the supervision of the European Central Bank (ECB) and within the perimeter of the SRB.

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 and the European sovereign debt crisis of the early 2010s, the European Union set out to create its common banking supervision and resolution mechanisms and outlined a vision for a common European deposit insurance system. Together these reforms amount to the formation of a European banking union, each reform constituting one of the banking union’s three pillars.1 The aim is to safeguard financial stability and, arguably, pave the way to deeper financial integration in Europe.2,3 However, the banking union is not yet a mission completed, especially in regard to a common European deposit insurance system.

New events often provide impetus for new development steps, and last year’s events in the US and Swiss banking sectors were no exception. US banks, particularly First Republic, Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, and in Switzerland Credit Suisse, once again brought the stability of the financial system under scrutiny. In this article we discuss some of the lessons that can be learnt from this, particularly with an eye to the further strengthening of the European banking union.

Our main conclusions are several. Although certain regulatory and supervisory shortcomings may have contributed to the events referred to, crisis resolution worked relatively swiftly. Arguably, having a unitary authority responsible for both resolution and deposit insurance, such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in the United States, is a crucial factor behind successful resolution. Similarly, it can be argued that a major improvement for the European banking union would be to bring bank resolution and deposit insurance under the same roof, a task that could be naturally entrusted to the Single Resolution Board (SRB). Importantly, this would require completion of the common European deposit insurance scheme, the EDIS. As a practical first step, the EDIS could be best implemented by including only the significant institutions which are directly under the supervision of the European Central Bank (ECB) and within the perimeter of the SRB.4

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: section 2 briefly reviews the central elements of an institutional setup aimed at safeguarding financial stability; section 3 then provides a comparison of the European and US experiences with bank resolutions; section 4 discusses policy implications; and section 5 sets out our conclusions.

A well-functioning institutional framework for safeguarding financial stability requires that there are at least three elements in place.

First, there have to be regulatory requirements with which the participants in the system comply. These aim to ensure a safe and sound financial system by requiring adequate capital and liquidity buffers in regulated financial institutions.

Second, there needs to be effective supervision of compliance with such requirements and of the management of risks that arise from individual participants and in the financial system. Supervision must be comprehensive and efficient.

Third, in view of the fact that even comprehensive regulatory and supervisory frameworks cannot prevent all banking failures and crises, it is necessary to have a “clean-up system” to deal with failures. An efficient clean-up system must take prompt, corrective action to ensure that robust solutions are implemented swiftly. Be it a resolution or a liquidation of a failed institution, an efficient clean-up system will ensure that non-viable market participants can fail in a controlled manner, while limiting contagion from their failure to other market participants and maintaining trust in the financial system.5

Such a clean-up system is an indispensable part of safeguarding financial stability and, to the extent possible, avoiding a bail-out that would use public funds.6 All these elements – regulation, supervision, and a clean-up system – are needed and are closely linked to each other.

In the recent bank distress of 2023, we saw all three elements at play.7 There were clear shortcomings in regulation and in supervision. However, the situation both in the US and Swiss bank failure cases was managed in a way that helped contain fears of global contagion. Below, we will focus on this third element, a clean-up system and its desirable institutional features, in the light of lessons learnt from the recent episode.

The bank resolution framework implemented in the EU is a very detailed clean-up system for bank failures.8 The European framework was in part inspired by the US system and informed by the detailed prescriptions of the Financial Stability Board. It is soon to celebrate its tenth birthday. The system is still young and quite comprehensive. It has been tested a few times already, albeit not for a globally systemically important bank or amid a systemic crisis.9 However, the question remains as to whether we in the European banking union could learn more from the US experience in devising and implementing an effective clean-up system. To address this question, we compare the US and European banking union solutions for resolving failing banks by considering three dimensions of a well-functioning resolution framework: speed, consistency and predictability. We also examine the interaction of resolution with deposit insurance.10

Speed

The architecture of the US bank crisis management system is centralized. In addition to being the deposit insurance authority, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) has supervisory powers and an autonomous authority to manage bank failures. The FDIC can manage both the transfer of a going concern business and the liquidation of assets.

In contrast, bank crisis management in the EU involves many authorities. First, there is a distinction between banking union and non-banking union Member States and authorities. In the banking union, the SRB is responsible for the biggest banks and national resolution authorities remain responsible for smaller banks. The SRB’s decisions are endorsed by the European Commission and the Council of the EU and are implemented by national resolution authorities. If the SRB finds no public interest in resolution, the failing bank is left to a national solution and may be put into insolvency or into liquidation. If the SRB needs to have recourse to deposit insurance funds, it will need to coordinate with the relevant authorities. If funding from the Single Resolution Fund (SRF) is to be used, approval by the European Commission from a competition perspective is also required.

The speed at which resolution procedures are initiated will hinge upon the triggers used for starting a resolution. Sufficient speed of the resolution procedures is an essential concern, because the longer that uncertainties prevail, the more damage will be caused as trust becomes strained and the risk of contagion increases.

In the United States, if a bank is deemed critically under-capitalized according to the relevant criteria, then its chartering authority, together with the FDIC, engages with the bank’s management and is subject to a time limit set by law – the Prompt Corrective Action provision. The authorities then have 90 days to appoint a receiver. If a chartering authority does not appoint a receiver, the FDIC may do so. There are also several other grounds for appointing a receiver, including balance sheet insolvency and illiquidity. Once receivership starts, many of the assets can already be marketed to potential buyers, even if the resolution of the entity has not yet been announced to the public.

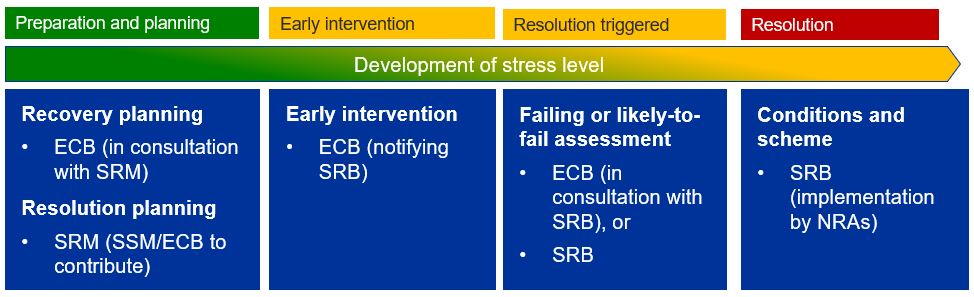

In the EU, and in the banking union in particular, where decision-making for significant banks is relatively centralized, the initiation of resolution follows a similar path. There are four different broad circumstances that can lead to failure being declared, triggering the resolution process. These are breaches or likely breaches that justify withdrawal of the banking licence, actual or likely illiquidity, actual or likely balance sheet insolvency, and, finally, a need for state aid to be provided. The resolution process for Significant Institutions requires a seamless interaction between the ECB Banking supervision and the Single Resolution Board (SRB) (see Chart 1). The ECB has the primary responsibility to determine whether a significant bank is failing or is likely to fail, but this can also be done by the SRB. In principle the SRB can contact potential buyers even before the bank is declared as failing.

Chart 1: The path to resolution of Significant Institutions

Source: Based on SSM materials.

Source: Based on SSM materials.

Regarding implications for the speed of resolution, the decision-making in the EU requires more coordination between the various authorities. The process is complex, especially in cases where multiple national authorities are involved.11 Furthermore, although the triggers for resolution are quite similar on both sides of the Atlantic, in the European banking union there is no exact equivalent of the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) clause, with its precise timeline. These two features, the need to coordinate among multiple authorities and the lack of a PCA equivalent, may slow down the European bank resolution process. The US system puts pressure on the authorities to avoid risks from inaction. The speed of resolution in the European banking union could probably be significantly improved by strengthening coordination and streamlining the roles of authorities, and by inserting triggering indicators with explicit timelines for action. The EU’s current dry runs play a very important role, in which the authorities, banks and stakeholders involved frequently conduct drills on whatever needs to be done in the event of a bank failure.12

Consistency and predictability

Experience from real resolution cases also matters. Learning by doing is an important mechanism to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the resolution system. In the United States, the FDIC has been in place since 1934, for almost 90 years, and has resolved an average of one bank a week in recent decades. It has handled cases ranging from small to fairly large-sized banks. In the period 2008–2013, the FDIC closed 489 banks, representing assets of almost USD 700 billion in total. Most of these banks were resolved through various types of asset acquisition and assumption of liabilities by other banks, and only 24 were liquidated with deposit payouts.

The European banking union’s Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) was created in 2014 and the system has so far been tested relatively little. While a number of banks have failed during its existence, only in two cases have significant banks been resolved: Banco Popular Espanol and the Slovenian and Croatian subsidiaries of Sberbank. In both cases the SRB decided to sell the relevant bank to a new owner. In the other cases, where a public interest in resolution was not found, different solutions for the failing banks were found. Two Italian banks, Veneto and Vicenza, were liquidated, using liquidation aid. ABLV Latvia’s shareholders decided to voluntarily liquidate the bank after the search for a buyer for its subsidiary was unsuccessful. PNB Banka entered insolvency shortly after its failure, and Sberbank Austria disposed of all its banking business and its licence lapsed.

In comparison with the FDIC, the number of resolution cases in the European banking union has been few, and many of the resolution tools have not yet been tested, except for the sale of business assets. A further observation is that where SRB resolution is not implemented, national solutions vary greatly. The outcome of a crisis management process is therefore difficult to anticipate. In contrast, in the United States the FDIC is also in charge of liquidation solutions, and the presumption is that situations will be resolved in the same manner that they have been for the past 90 years.

The recent European Commission proposal for a crisis management and deposit insurance framework (CMDI) could be a step forward.13 It would extend the resolution perimeter by lowering the so-called public interest assessment threshold, i.e. making it more likely that a failing bank would be resolved rather than liquidated or put into insolvency. Even though national resolution authorities would still be responsible for managing the failure of these banks, their decisions, in contrast to national deposit guarantee authorities and bankruptcy administrators, would be overseen by the SRB to ensure equal treatment across the European banking union. The harmonized treatment of small and medium-sized banks in the banking union would enhance consistency and predictability of national solutions.14 However, the new proposal would not effectively tackle the problems in cases of cross-border financial institutions that are subject to several national deposit guarantee schemes (DGSs) with different structures and decision-making systems.

Funding and interaction with deposit insurance

Finally, let us consider funding in resolution and the role of deposit insurance systems in this regard.

In the United States, the FDIC manages bank failures and, as the deposit insurer, operates a deposit insurance fund, to which it can have recourse. It can also borrow from the Treasury. So far, the FDIC’s funding has been sufficient. As already mentioned, in the period 2008–2013 the FDIC needed around USD 68 billion to resolve banks with total assets of close to USD 700 billion. It is quite likely that recourse to its resolution tools rather than straight liquidation of assets and depositor payout have contributed to this manageable cost.15

In the European banking union, the SRF’s target level is roughly EUR 80 billion. The national deposit insurance schemes have total funds of EUR 37 billion. Hence, the total amount may not be too far from the FDIC’s resources. However, the use of SRF funds to recapitalize a bank is subject to a strict condition, a bail-in obligation of 8% of total liabilities. There is also a cap, amounting to 5% of the total assets of the failing bank, on the amount that can be used from the SRF.16 Funds from the SRF can also be used to cover potential substantial liquidity needs to ensure the efficient implementation of resolution tools.

In addition, Member States have agreed that the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) will provide a backstop to the SRF under certain conditions, although the agreement has not yet been ratified by all Member States. The SRB’s recourse to deposit guarantee funds is at this stage limited. Such recourse is further limited by the size of the individual national funds. In cases where several national DGSs are participating, implementation of recourse to these national funds becomes quite complicated as their structures, decision-making procedures and funding levels vary country by country.

Improved coordination and pooling of the financial resources in the resolution framework with the deposit insurance system could be highly beneficial for the banking union, not only for funding reasons but also for creating more feasible options for resolution.17 In this regard, the differences between the US and the European banking union seem particularly pronounced.

In the United States, the FDIC considers all aspects in safeguarding depositors’ rights. For instance, it has the power to transfer deposits to another institution. Furthermore, it can decide when to use funds from the deposit insurance fund.

In the European banking union, the interaction with deposit insurance is more complicated. The resolution authority focuses on protecting depositors’ interests, but a payout by a DGS can also be deemed to satisfy this objective. If the SRB does not find public interest in resolution, its duties stop there, and it would not be able to transfer deposits to another legal entity. A strict least cost test and a tiered depositor preference also do not facilitate a broader use of deposit guarantee funds that would possibly limit the overall cost of failures. However, the European Commission is willing to change these elements to facilitate the use of DGS funding.18 As already discussed, the idea is to expand the set of cases in which a DGS can intervene to support a non-payout solution by introducing a general depositor preference and by enabling the use of DGS funds to facilitate transfer strategies in cases where deposits would otherwise be written down or converted.19

What are the lessons to be learnt from these reflections for the further strengthening of the European banking union’s institutional setup? Overall, as the US experience suggests, integration of deposit insurance in the resolution process, with the objective of facilitating resolution and reducing its total cost, can be an efficient solution. Creation of a European deposit insurance scheme (EDIS) could therefore be highly beneficial, especially for managing failures of significant cross-border banking groups.20,21 Resolving such bank failures would be difficult in the current system, because the financial resources and powers of any national deposit insurance system are limited. Hence, to reap the full benefits, there should also be a single authority in the banking union to take care of both resolution and deposit insurance.22

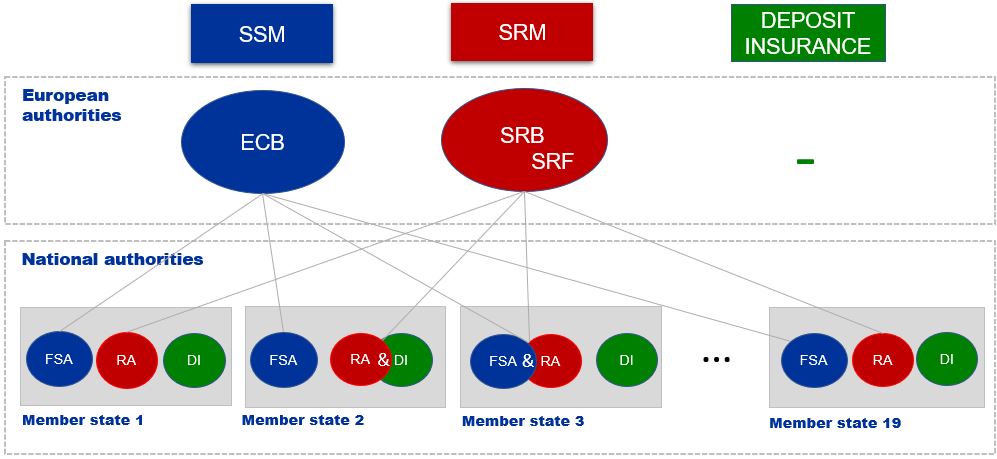

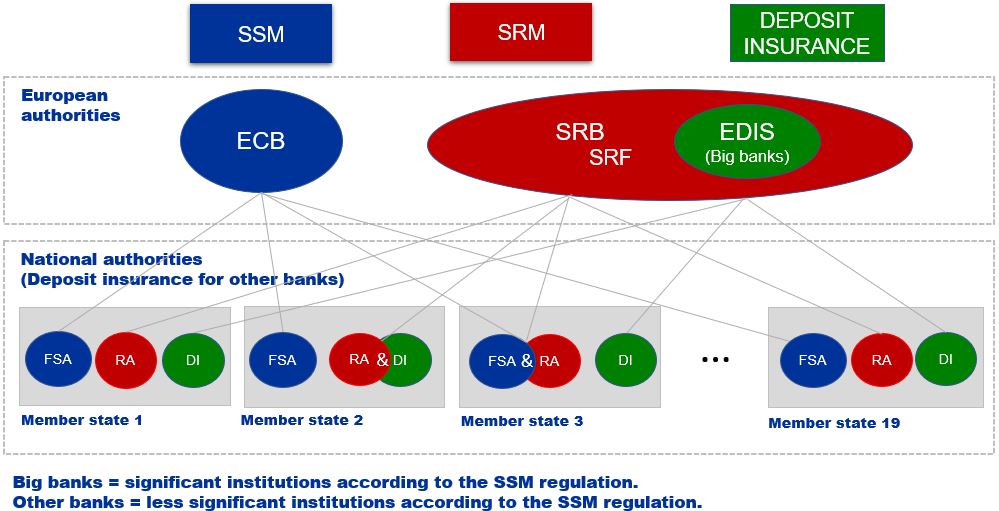

When contemplating the way forward, it is important to recognize that in today’s set-up there is no single authority at the European level responsible for deposit insurance matters; these have to be dealt with by national deposit insurance systems. As the SRB has to determine the resolution scheme taking into account all assets and liabilities of a troubled bank, one logical possibility could be to expand the mandate of the SRB to act as a deposit insurance authority for the significant institutions (see Charts 2 and 3).23

Chart 2: The banking supervision and the resolution mechanism in the Banking Union

Chart 3: A unitary authority for resolution and deposit insurance for the big banks in the Banking Union

The SRB’s role as deposit insurance authority would primarily entail use of DGS funds to finance resolution measures, as applying resolution would most likely be in the public interest if a large and complex bank should fail. The SRB has the required expertise in using resolution measures in cross-border cases and it would have to deal with deposits in resolution cases anyway. In addition, as already discussed, the SRB together with the national DGSs would have financial capacity comparable to that of the FDIC, which would facilitate the transfer to the EDIS.24,25

Such a solution would be consistent with the current structure of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM).26 The SRB would then be a unitary authority like the FDIC in the United States. With a unitary authority, crisis management and the key source of funding for resolution (i.e. the common deposit insurance) would unambiguously lie within the same institution. This would considerably simplify decision-making compared to the current system. Moreover, it may create institutional incentives for prompt corrective action when the institution determining resolutions is responsible for minimizing deposit insurance payouts. The decision-making system could reflect the current set up of the banking union resolution and supervision frameworks. Overall, the prerequisites for a strong funding base for the EDIS would be there: deposit insurance would have to be ultimately funded by the banking industry; the SRF already has considerable resources; and national systems are in place, possibly able to release funds to the new common system as the significant banks would be moved within the perimeter of the SRB.27

Regulation, supervision and crisis management are complementary and necessary elements for financial stability. Designed and run in an appropriate manner, they will curb excessive risk-taking and help to avoid publicly funded bailouts of failed financial institutions and minimize adverse effects of their failure for society as a whole. Because bank failures can never be fully avoided, a robust resolution framework is needed as a backstop. It should be swiftly acting, predictable and credible. A prompt and efficient resolution procedure together with the bail-in principle is key to building trust in the resolution framework and thereby reinforcing market discipline.

The recent bank runs, and particularly the speed and magnitude of the liquidity outflows surprised many observers. They underscored the importance of quick action by the authorities. Fair treatment of depositors and other creditors has been another central issue.

The European banking union has its own framework in place for handling banking crises. However, further reforms are needed in order to simplify and speed up decision-making, improve consistency and predictability, and enhance interaction between resolution and deposit insurance.

To meet these goals, it would be advisable to move forward with the European Commission’s EDIS proposals, all the way to completion of the common deposit insurance scheme for the European banking union. Responsibility for bank failure resolution and deposit insurance in the banking union should lie with a unitary authority, a role that could naturally be entrusted to the SRB. Perhaps as a practical first step, the EDIS could cover only the big banks that are already within the SRB’s perimeter.

Barr, M.S. (2023). Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank, 28 April 2023. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Beck, T., Laeven, L. (2006). Resolution of failed banks by deposit insurers: Cross-country evidence (Vol. 3920). World Bank Publications.

Bolton, P., Oehmke, M. (2019). Bank resolution and the structure of global banks. Review of Financial Studies, 32(6), 2384-2421.

Brunnermeier, M.K., S. Langfield, M. Pagano, R. Reis, S. Van Nieuwerburgh, D. Vayanos (2017). ESBies: safety in the tranches. Economic Policy 32: 90, 175–219. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eix004.

Carmassi, J., Dobkowitz, S., Evrard, J., Parisi, J., Silva, A.F., Wedow, M. (2020). Completing the Banking Union with a European deposit insurance scheme: Who is afraid of cross-subsidization? Economic Policy 35:101, 41–95. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiaa007.

Crabb, John (2018). Primer: A comparison of EU and US bank resolution regimes. https://www.iflr.com/article/2a63cuwbv4ay6rzn75iio/primer-a-comparison-of-eu-and-us-bank-resolution-regimes.

De Haan, J. (2022). Institutional Protection Schemes in German Banking. In-depth analysis requested by the ECON committee. European Parliament, April 2022.

EBA (2021). Report on the application of early intervention measures in the European Union in accordance with articles 27-29 of the BRRD. European Banking Authority, EBA/REP/2021/12.

Enria, A. (2021). Crisis management for medium-sized banks: The case for a European approach. ECB speeches.

Enria, A. (2022). Of temples and trees: On the road to completing the European banking union. ECB speeches.

European Commission (2023). Reform of bank crisis management and deposit insurance framework. 18 April 2023. Available at: Reform of bank crisis management and deposit insurance framework (europa.eu).

FDIC (1998). A brief history of deposit insurance in the United States. Prepared for the International Conference on Deposit Insurance, Washington, D, September 1998. Available at: A Brief History of Deposit Insurance (fdic.gov).

FDIC (2023). Bank resolutions and receiverships. In Crisis and response: An FDIC history, 2008-2013. https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/crisis/chap6.pdf.

French, K.R., Baily, M.N., Campbell, J.Y., Cochrane, J., Diamond, D.W., Duffie, D., Kashyap, A.K., Mishkin, F.S., Rajan, R.G., Scharfstein, D.S., Shiller, R.J., Shin, H.S., Slaughter, M.J., Stein, J.C., Stulz, R.M. (2010). The Squam Lake Report: Fixing the Financial System. Princeton University Press.

FSB (2011). Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions. Financial Stability Board, October 2011.

FSB (2023). 2023 Bank Failures: Preliminary lessons learnt for resolution. Financial Stability Board, 10 October 2023.

Gelpern, A. and N. Véron (2019). An effective regime for nonviable banks: US experience and considerations for EU reform. European Parliament, ECON Committee, July 2019. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/624432/IPOL_STU(2019)624432_EN.pdf.

Hakkarainen, Pentti (2023). Indispensable elements for the banking union: Observations on the US experience. Keynote speech at the International Capital Markets Conference, organized by Deutsche Bundesbank, KfW, the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum (OMFIF) and DZ Bank on 9 May 2023 in Frankfurt, Germany.

Hellwig, M.F., Sapir, A., Pagano, M., Acharya, V., Balcerowicz, L., Boot, A., Brunnermeier, M.K., Buch, C., van den Burg, I., Calomiris, C., Gros, D., Focarelli, D., Giovannini, A., Ittner, A., Schoenmaker, D., Wyplosz, C. (2012). Forbearance, Resolution, Deposit Insurance. ESRB: Advisory Scientific Committee Reports 2012/1, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3723321 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3723321.

IADI (2023). The 2023 banking turmoil and deposit insurance systems: Potential implications and emerging policy issues. International Association of Deposit Insurers, December 2023.

Jiang, E.X., Matvos,G., Piskorski, T., Seru, A. (2023). Monetary tightening and U.S. bank fragility in 2023: Mark-to-market losses and uninsured depositor runs? NBER Working Paper 31048.

Jokivuolle, E., Pennacchi, G. (2019). Designing a Multinational Deposit Insurance System: Implications for the European Deposit Insurance Scheme. ifo DICE Report, 17(1), 21-25.

Jokivuolle, E., Vihriälä, V., Virolainen, K., Westman, H. (2020). Bail-in: EU rules and their applicability in the Nordic context. Nordic Economic Policy Review, 2020.

Martinez, J., Philippon, T., and Sihvonen, M. (2022). Does a currency union need a capital market union? Journal of International Economics, 139.

Restoy, F. (2019). How to improve crisis management in the banking union: a European FDIC? SUERF Policy Note, Issue No. 102, September 2019.

SRB (2023). Small and medium-sized banks: Resolution planning and crisis management report for less significant institutions in 2022 and 2023. Single Resolution Board, October 2023.

Tröger, T.H., Kotovskaia, A. (2023). National interests and supranational resolution in the European Banking Union. European Business Law Review 34:5, 781-800. Available at: https://kluwerlawonline.com/journalarticle/European+Business+Law+Review/34.5/EULR2023038

Véron, N. (2017). Sovereign concentration charges: A new regime for banks’ sovereign exposures. The European Parliament, Economic Governance Support Unit. November 2017.

See e.g. Council of the European Union: Banking union https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/banking-union/. There is also an EU initiative to create a capital markets union for the European Union.

On the welfare benefits of financial integration in a currency union, see e.g. Martinez et al. (2022) and the literature cited therein.

Proposals to create a common safe asset for a currency union (without a fiscal union) can also be seen as an initiative to advance these goals, especially by helping to break the “bank-sovereign doom loop” that emerged during Europe’s sovereign debt crisis (see e.g. Brunnermeier et al. 2017). Véron (2017) discusses the direct bank-sovereign linkages via national deposit insurance and concentrated domestic sovereign exposures by euro area banks and proposes that together with a common European deposit insurance, regulation of concentrated sovereign exposures of euro area banks should be considered.

Restoy (2019) has identified potential adverse implications of the singularities of the banking union’s current crisis management system and sketched a few options to improve the system. The outcomes of our analysis are not inconsistent with the options he discusses; however, we would see implementation of the EDIS for big banks first as the most feasible option instead of covering all (almost 4000) banks in the banking union.

On the term “resolution” see e.g. FSB (2011).

For instance, the well-known Squam Lake Report (see French et al. 2010), published soon after the global financial crisis, puts a lot of emphasis on developing ideas to recapitalize banks without recourse to taxpayer funds.

For an account of the events, see e.g. Barr (2023), FSB (2023) and Jiang et al. (2023).

For a description, see e.g. Jokivuolle et al. (2020).

See European Banking Authority, Notifications on resolution cases and use of DGS funds | European Banking Authority (europa.eu).

Interaction of bank resolution with deposit insurance has been studied by e.g. Beck and Laeven (2006), who find that banks are more stable in countries where the deposit insurer has a responsibility to intervene in failed banks. A report by the European Systemic Risk Board points to potential synergies in operating the two functions within the same institution and emphasizes the importance of having clear rules on coordinating actions in the case they are organized in separate institutions (see Hellwig et al. 2012). The International Association of Deposit Insurers also argues that, to be effective, the “deposit insurance system must work in synergy with the frameworks for prudential regulation, supervision, and resolution” (see IADI 2023).

Cf. Tröger and Kotovskaia (2023).

Similar issues to those discussed in this subsection have also been discussed in EBA (2021).

See European Commission (2023).

Proposals to harmonize the resolution treatment of small and medium-sized banks are also discussed in SRB (2023).

Note that while the FDIC provided over USD 1 trillion in guarantees during the last financial crisis, subsequent amendments to the relevant law have limited the FDIC’s ability to provide emergency financial support to individual institutions, except as part of a liquidation process.

Neither of the two resolution cases implemented in the banking union so far have made any recourse to the resolution fund.

Advantages of centralized decision-making in the context of bank resolution are analysed in e.g. Bolton and Oehmke (2019).

See European Commission (2023).

Recall, however, that as argued earlier, the new proposal still falls short of proposing a convincing solution to the issue of resolving cross-border financial institutions efficiently.

The general motivation for a cross-border deposit insurance system in the European context has been discussed by e.g. Jokivuolle and Pennacchi (2019). They also discuss the fair pricing of a multinational deposit insurance system, which would help alleviate concerns of cross-border “subsidies” (which in turn might be seen as a feature of a “transfer union”).

An interesting point of reference for the advancement of the EDIS is the historical development of the FDIC in the US. Two features stand out. First, before the creation of the FDIC many states had their own deposit insurance system, and second, a major banking crisis (bank failures of the 1920s) provided impetus for the final reform (see FDIC 1998).

According to the International Association of Deposit Insurers, “(o)ver the past decade, there is a clear trend for deposit insurers’ mandates to broaden to include resolution functions” (see IADI 2023, Box 1, page 12).

The total market share of these banks, directly supervised by the ECB, is currently over 80% (see Publication of supervisory data (europa.eu)).

The challenge with such an approach is that part of the funds of national DGSs would need to be transferred to the centralized fund, possibly leaving the national DGSs responsible for other banks under increased cost pressure. Such concerns could raise questions regarding a level playing field and financial stability, e.g. a possible “cliff effect” in the form of large flows of customer and creditor funds from nationally covered banks to those covered by the EDIS. However, the long-run effect on financial stability of a partial (although quite comprehensive) implementation of the EDIS in the banking union should be assessed in relation to the prevailing situation, which is solely based on national deposit insurance systems.

The business model of systemically important banks is often complex, multinational and quite distinct from that of smaller, locally oriented banks. Furthermore, major financial crises typically involve failures of large financial institutions. There may therefore be an argument for having separate deposit insurance systems for these two groups of banks, in which deposit insurance fees would be set by considering potentially different risk profiles of the two groups of banks.

If there are specific national DGSs, like the German Institutional Protection Scheme (IPS), these could be integrated as complementary systems providing additional coverage to the banks in question. See also De Haan (2022).

Carmassi et al. (2020) studied the implications of the EDIS using unique supervisory data and found that a target size of 0.8% of euro area covered deposits for an ex ante funded deposit insurance fund would have been sufficient to cover losses in a severe banking crisis (even more than those that materialized in the 2007–2009 crisis).