Acknowledgement: We are grateful for the comments received from Jochen Mankart and Ádám Banai.

Abstract

The integration into the EU regulatory and supervisory framework has played a crucial role in successfully stabilizing and aligning CESEE financial sectors with the other EU countries. Non-performing loans dropped from around 11% after the GFC to around 3% nowadays, while Solvency ratios increased from 12% to more than 20% in the same period. At the same time, some CESEE-specific structural features remain in place. CESEE banking systems are mostly foreign-owned and strongly oriented towards ‘plain vanilla’ type of banking activities, in particular loans to households and corporates. Moreover. CESEE financial sectors remain relatively small compared to the size of these economies and heavily bank-centric. Looking at corporate lending, there are some concerns that CESEE banks may be over-conservative in their lending practices, questioning the financing for corporate growth and innovation. Looking forward, regulatory simplification should be considered and market-based financial mechanisms should be strengthened to provide more flexible and innovative funding opportunities for businesses. These measures should also help in developing the financial systems in potential new EU member states.

The financial sectors of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe (CESEE) have experienced substantial development during the last decades. In the late ‘90s and early 2000s there were still fears that the lack of institutional infrastructure, weak regulatory frameworks, and the dominance of state-owned banks would hinder financial development and increase the vulnerability to crises (Thimann, 2002). However, financial sectors in these countries were successfully liberalized, restructured and privatized, with strong involvement of foreign strategic investors (Bokros, 2001). After the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), there was an increased focus on financial stability, with a shift towards more diversified funding sources, reduced reliance on foreign parent banks (Lahnsteiner, 2020) as well as stronger micro- and macroprudential supervision (Iwanicz-Drozdowska and Witkowski, 2020).

In this policy brief, we look at key features of CESEE financial systems 35 years after transition and more than 20 years after EU enlargement. We assess some important financial stability indicators, and we ask whether the CESEE financial sectors are fully prepared for the current challenges that the CESEE region as well as the EU as a whole is facing, including the need to finance more competitiveness-enhancing investments and to speed up the green transition. Now is a good time to ask these questions, first and foremost for the CESEE region itself. Moreover, the lessons from the transformation of CESEE financial sectors can also contain important messages for future accession countries, especially given the current turbulent geopolitical times.

Since the early 2000s, the financial sectors of CESEE countries are characterized by a high level of foreign ownership, with many banks being subsidiaries of Western European parent banks.1 This ownership structure has strongly influenced CESEE banking sectors and led also to some differences of the activities of parents and subsidiaries. While more complex operations remain under the aegis of parent banks, the subsidiaries in CESEE countries concentrate on traditional domestic banking activities, such as granting loans to households and domestic businesses. This is relatively straightforward and in line with the aim of the parent banks’ decision to invest into CESEE countries to benefit from the potential in financing these economies.

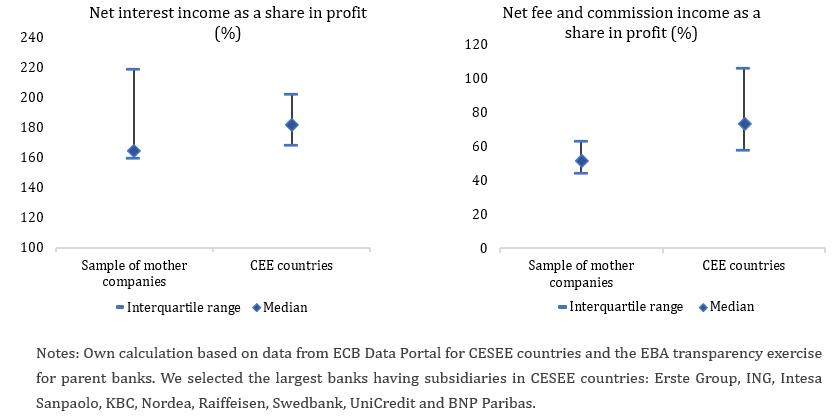

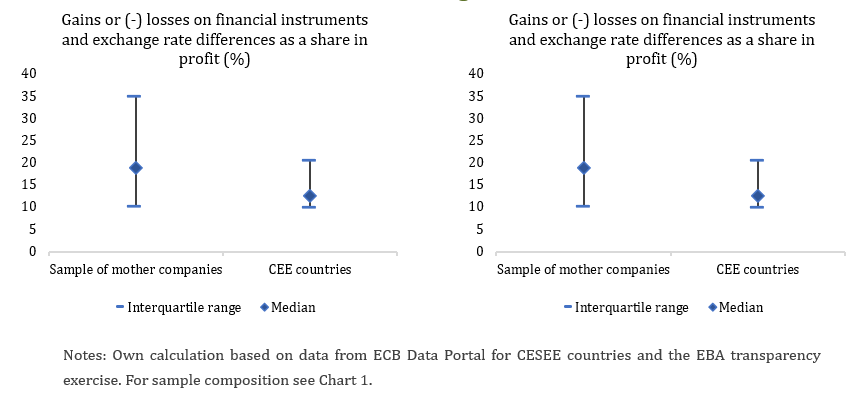

Differences in the activities between parent banks and subsidiaries can be seen in banks’ income sources.2 The importance of net interest income and net fee and commission income for overall profits is somewhat larger for CESEE banks compared to the parent banks (Chart 1). By contrast, median income from financial instruments and trading assets is higher and represent a larger share of total assets for parent banks than for CESEE banks, as visible from Chart 2.

Chart 1. Traditional banking activities

Chart 2. Trading activities

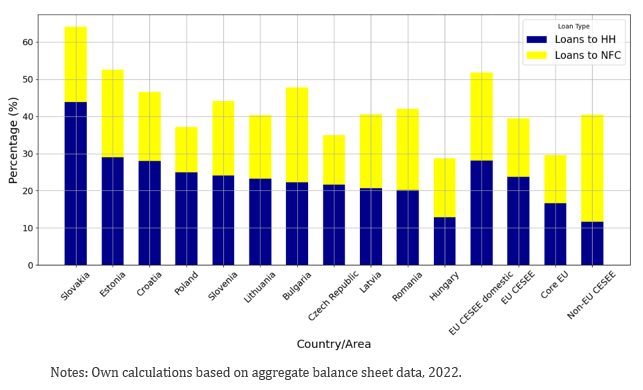

The composition of loans assets in CESEE banks further highlights their focus on traditional banking activities. Chart 3 shows that the share of loans to households (HH) and Non-Financial Corporations (NFCs) in per cent of total assets is significantly higher in CESEE countries compared to banks in other EU countries. Going one step further and distinguishing between foreign-owned and domestically-owned banks in CESEE – the latter being a substantially smaller part of the banking sector – reveals that domestic CESEE banks have an even larger share of loans to households and NFCs. This suggests that domestic CESEE banks are concentrated on serving retail clients and businesses.3 Foreign-owned subsidiaries have a somewhat broader focus, although still less so than their parents. Connecting these findings to the research of Lahnsteiner (2020) and Iwanicz-Drozdowska and Witkowski (2020), it becomes evident that parent banks and subsidiaries serve different market segments.4

Banks in non-EU CESEE countries, have a much lower share of loans to households relative to total assets. However, the share of loans to NFCs is proportionally higher, so the overall share of loans to HH and NFCs is similar in EU and Non-EU CESEE.

The focus of foreign-owned and – even more so – domestically-owned CESEE banks on traditional banking activities, supports the stability of the banking sector. However, it also suggests that there may be a need for a broader development of financial services beyond traditional banking. For future EU accession candidates, this suggests that efforts to achieve a more diversified financial landscape may need to be strengthened and front-loaded.

Chart 3. Composition of loans (% of total balance sheet) by country in 2022

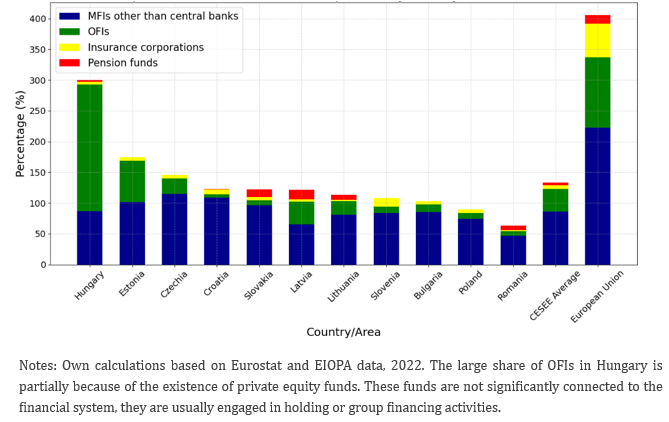

The financial sectors of CESEE countries are relatively small compared to other EU countries and are primarily bank centric. Chart 4 shows that the financial sectors in CESEE countries are dominated by banks (monetary financial institutions ‘MFIs’), with only limited contributions from other financial intermediaries (OFIs), insurance corporations, and pension funds.

This structure, as already indicated in the previous section, has both advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, the strong focus on traditional banking activities, such as lending to households and small businesses, makes banks in the region less directly exposed to large financial market shocks. On the other hand, the limited development of alternative financing sources, such as market-based finance and venture capital, restricts the ability of firms to diversify their funding, limits their access to more sophisticated financial products and may hamper corporate growth and innovation. In fact, existing empirical research questions to what extent bank credit, especially lending by foreign-owned banks, is really an important source of economic growth in CESEE (Iwanicz-Drozdowska and Witkowski, 2020).

There is plenty of work suggesting that stronger market-based finance, more venture capital, and – more generally – more provision of non-bank financial services provides firms with greater flexibility in their funding choices and supports corporate growth and innovation. Venture capital plays an important role in financing innovation (Lerner & Nanda, 2020). It’s existence typically requires, however, a critical size of a stock market, which in turn is hard to achieve in bank-based systems (Black & Gilson, 1998). In fact, lack of market-based venture capital often results in the relocation of promising European Start-Ups to other jurisdictions, mainly the U.S. (Weik et al., 2024). Fintech and digital finance initiatives also provide alternative funding sources, but their occurrence is often connected to less stringent banking regulation and a regulatory ease of doing business (Cornelli et al., 2023).

Chart 4. Size and composition of financial sector components by country (% of GDP) in 2022

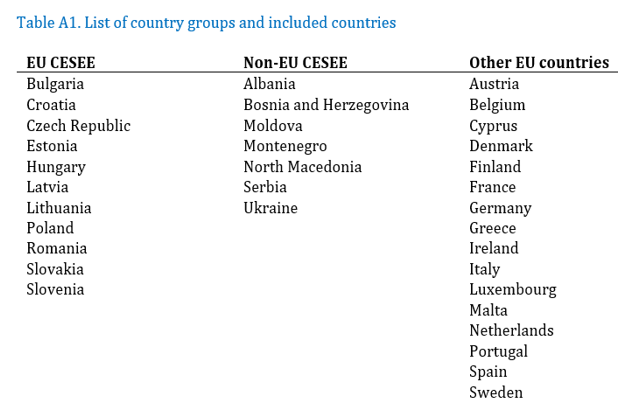

Besides being bank-centric, the CESEE financial sectors are also very stable over time, compared to the size of the economies. Bank balance sheets in EU CESEE countries mostly fluctuated between 80 to 90% of GDP between 2015 and 2022 (Chart A1). This is a substantially smaller aggregate banking sector that in the EU as a whole and may in fact be smaller than optimal, given the state of economic development (Popov, 2017). This in turn raises the question why CESEE banking sectors are not further developing and what potential solutions could look like.

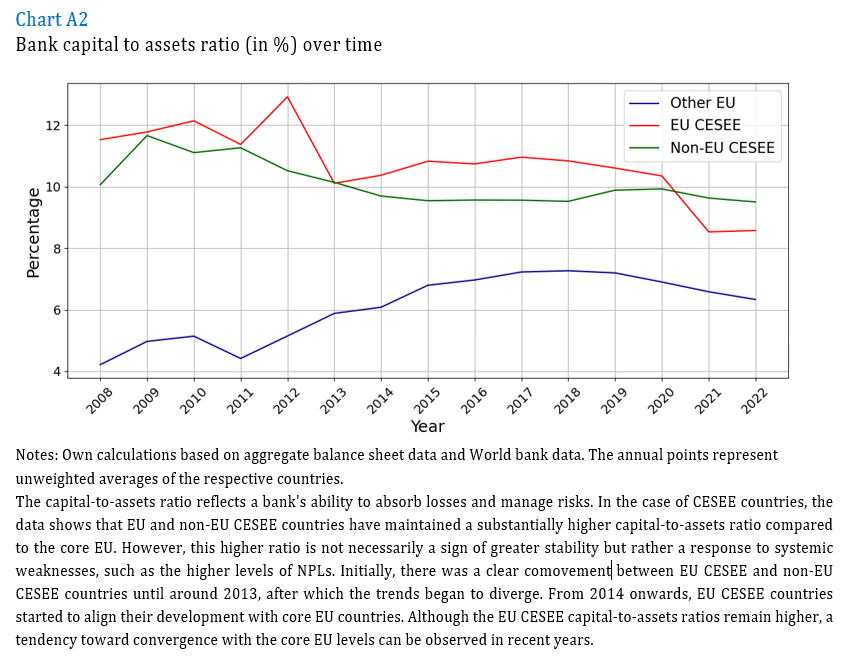

CESEE financial sectors have become a lot more stable after the GFC, which is very good news. Stable financial systems are essential for economic growth, ensuring that banks can absorb shocks and continue lending during times of stress. As far as stability is concerned, banking sectors in EU CESEE-countries benefit from EU-membership and common prudential banking regulation. By contrast, non-EU CESEE countries have in general more costly banking services and their financial markets are usually riskier for investors (Vunjak et al., 2020).

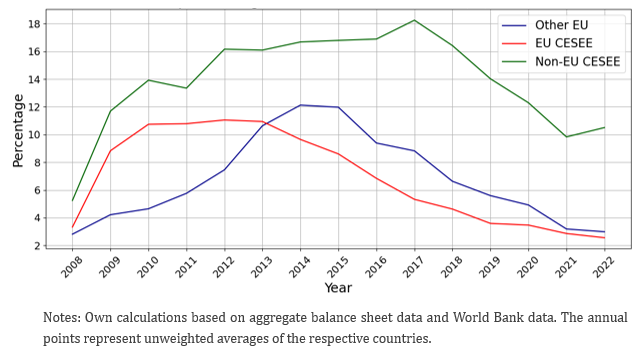

NPL ratios of EU CESEE countries are now more aligned with those of other EU countries. To assess banking sector stability, we look at non-performing loans (NPL) and solvency ratios over time. The NPL ratio practically measures the percentage of loans that have not been serviced for more than 90 days (Chart 5). Until around 2011, there was a clear comovement between the NPL ratio in non-EU CESEE and EU CESEE countries. After2011, the trends began to diverge5.From 2014 onwards, EU CESEE countries started to exhibit a pattern similar to that of the other EU countries, with NPL ratios declining steadily to very low levels. This suggests that the integration of EU CESEE countries into the broader European financial and regulatory framework took considerable time and required substantial structural and regulatory enhancements, including more conservative lending practices, which make it harder to receive a loan. Second, however, the alignment with the EU eventually helped to stabilize the financial systems of EU CESEE countries.

Chart 5. Bank nonperforming loans to total gross loans ratio (in %) over time

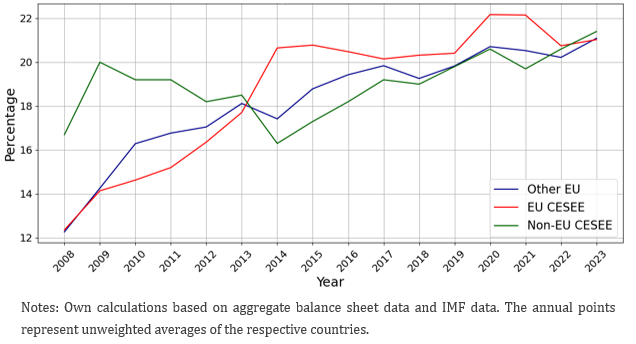

Solvency ratio shows an upward trend in all country groups during the period followed. The solvency ratio, which measures the capital relative to risk-weighted assets, reflects a bank’s capacity to absorb losses and manage risks effectively. Throughout the period we see an upward trend and a strong comovement between EU CESEE countries, the rest of the EU and since 2014 also the non-EU CESEE financial sectors. For most of the period, capital ratios in the CESEE financial sectors were, however, somewhat higher suggesting again a more conservative approach than in the rest of the EU.

Chart 6. Solvency ratio (in %) over time

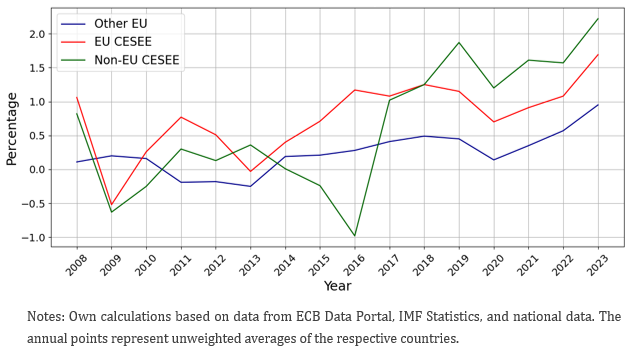

Profitability of EU CESEE banks is sound and outperforms banks in other EU countries. A banking sector’s stability is strongly impacted by the profit the sector can generate, as retained earnings are an important source of own funds. Similar to NPLs, developments in EU CESEE and other EU financial sectors are broadly aligned although EU CESEE financial sectors tend to be more profitable. Developments in non-EU CESEE financial sectors tend to be a lot more volatile. Whereas banking sector profitability tends to have a positive impact on banking sector stability, the relatively high profitability of EU CESEE and – more recently – also non-EU CESEE can also indicate a lack of competition, which can potentially hamper efficient and affordable lending.

Chart 7. Bank return on assets (in %) over time

Overall, the data suggests that CESEE financial sectors, in particular those of EU countries came a long way towards lasting financial stability with fewer distressed assets, higher capital levels and sound profitability, often exceeding the figures for the non-CESEE EU countries.

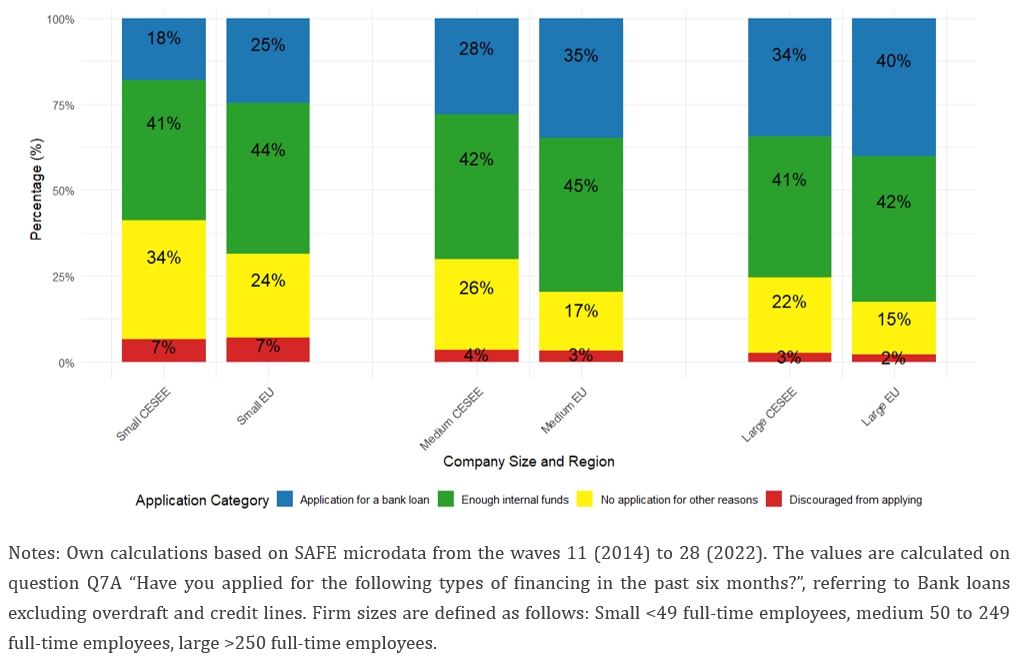

Access to bank-based financing is a particularly important economic factor for SMEs throughout Europe, especially in heavily bank-centric financial systems, such as those in CESEE. While the preceding sections have focused on structural features of the banking sector, a complementary perspective can be gained by looking at firm-level applications for bank loans. The Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE) is particularly valuable in this regard as it captures not only whether firms apply for loans but also their reasons for not applying.

Survey results from SAFE show that some categories of bank loan application behaviour differ substantially across regions. In both CESEE and other EU countries, the share of firms discouraged from applying—those who feared rejection—is relatively small and comparable (Chart 8). Likewise, the share of firms reporting sufficient internal funds is broadly similar across regions. However, CESEE firms are significantly more likely to not apply for loans for “other reasons”. This behavior is especially strong among small firms, but it is evident across all size classes. As a result, the overall loan application rate in CESEE is consistently lower than in the rest of the EU. The data suggest that CESEE firms are holding back not because they cannot access finance, i.e. fearing or expecting rejection either wazy, or do not need it, but because they choose not to engage with the formal bank loan application system.

A potential explanation of the lack of applications for loans can be the negative perception of firms in CESEE. Firms in CESEE may anticipate unfavorable loan conditions, including high interest rates, excessive collateral demands, or extensive administrative processes. These perceptions might reflect real structural issues: as discussed earlier, CESEE banks exhibit high profitability, which may also indicate limited competition and a less favorable environment for affordable and inclusive lending. Research using similar surveys suggests that such firms often do not update their beliefs, even when financing conditions improve. Past negative experiences, or simply the expectation of a negative outcome, can result in persistent credit avoidance—particularly among SMEs (Fidrmuc & Horky, 2023). This dynamic implies a risk of self-constraining behavior, where firms forgo growth opportunities due to outdated or pessimistic beliefs about access to finance. However, a negative and reinforcing cycle can potentially occur: If viable firms do not seek funding, financial markets cannot evolve to support innovation and growth.

Chart 8. Comparison of firms’ bank loan application behavior in CESEE and other EU countries

The financial sectors of CESEE countries have made significant progress. The integration into the EU regulatory and supervisory framework has played a crucial role in successfully stabilizing these financial systems, especially after the Great Financial Crisis in 2007/2008. At the same time, some CESEE-specific structural features remain in place. Foreign ownership remains a defining characteristic of CESEE banking systems and CESEE financial sectors remain relatively small compared to the size of these economies, heavily bank-centric and strongly oriented towards ‘plain vanilla’ type of banking activities, in particular loans to households and corporates.

There are some concerns that CESEE banks may be over-conservative in their lending practices, raising questions about the financing for corporate growth and innovation. CESEE banks generate higher returns on assets while maintaining very low risk portfolios. This suggest that they operate with a particularly conservative business model, which in turn may unduly restrict financial access, especially for smaller and younger firms including start-ups. Banks and corporates may, however, face a chicken-and-egg problem. Without viable business models and innovative firms seeking funding, financial markets will struggle to expand. At the same time, without more competitive and dynamic financial markets, firms lack the necessary capital to grow and innovate. If this diagnosis is correct, policy intervention is required to break this cycle, e.g. in the form of public loan guarantees to start-ups and a simplification of banking regulation.

Moving beyond banks, alternative, market-based financial mechanisms should be strengthened to provide more flexible and innovative funding opportunities for businesses. Small and developing financial markets such as in the CESEE countries, often struggle to muster a critical mass of financial activity. Deeper European integration as envisaged through Capital Markets Union or the Savings and Investment Union is crucial to overcome this problem and to “…achieve simplification through European harmonization“(Elderson, 2025). Beyond banking and market-based finance, fintech provides opportunities for enhancing competition in CESEE financial sectors. Digital lending, cross-border peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms, and decentralized financial solutions could provide alternative funding sources for businesses and households.

For potential future EU enlargement, key lessons emerge from the CESEE experience: First, the regulatory trajectory for future accession countries may need to be reconsidered. Full regulatory exposure of still developing financial sector may not be optimal. Instead, new member states should be granted a more gradual transition period to allow their financial systems to develop sufficiently. Second, the development of the European capital market should be seen as a priority not just for current but also for future member states, all of which currently have low levels of financial intermediation. Third, future member states should be encouraged to develop alternative financing options. Initiatives such as cross-border investment frameworks and regulatory sandboxes for fintech could play a crucial role in accelerating financial sector development.

Black, B. S., & Gilson, R. J. (1998). Venture capital and the structure of capital markets: banks versus stock markets. Journal of financial economics, 47(3), 243-277.

Bokros, L. (2001). Banking Sector Reform in Central and Eastern Europe. In: Saleh, M., Nsouli, M. & Havrylyshyn, O. (2001) A Decade of Transition. Achievements and Challenges. IMF, ISBN: 9781589060135

Cornelli, G., Frost, J., Gambacorta, L., Rau, P. R., Wardrop, R., & Ziegler, T. (2023). Fintech and big tech credit: Drivers of the growth of digital lending. Journal of Banking & Finance, 148, 106742.

Efthyvoulou, G., & Yildirim, C. (2014). Market power in CEE banking sectors and the impact of the global financial crisis. Journal of Banking & Finance, 40 , 11-27.

Elderson, F. (2025). Resilience offers a competitive advantage, especially in uncertain times. Keynote speech by Frank Elderson, at the Morgan Stanley European Financials Conference. London, 19 March 2025

Fidrmuc, J., & Horky, F. (2023). Experience and Firms’ Financing Behavior: A Behavioral Perspective. German Economic Review, 24(3), 233-269.

Iwanicz-Drozdowska, M., & Witkowski, B. (2020). Dancing the Viennese waltz or just doing business? The policy of parent banks in CESEE countries. Post-Communist Economies, 32 (6), 726-748.

Lahnsteiner, M. (2020). The refinancing of CESEE banking sectors: What has changed since the global financial crisis?. Focus on European Economic Integration, (Q1/20), 6-19.

Lerner, J., & Nanda, R. (2020). Venture capital’s role in financing innovation: What we know and how much we still need to learn. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(3), 237-261.

Popov, A. (2017). Evidence on finance and economic growth. European Central Bank Working Paper Series, (2115).

Thimann, C. (Ed.). (2002). Financial sectors in EU accession countries (Vol. 488). Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

Vunjak, N., Dragosavac, M., Vitomir, J. & Stojanovic P. (2020). Central and South-Eastern Europe banking Sectors in the Sustainable Development Function. Economics, 8(1), 51-60

Weik, S., Achleitner, A. K., & Braun, R. (2024). Venture capital and the international relocation of startups. Research Policy, 53(7), 105031.

The median share of foreign subsidiaries and branches in total assets among CESEE countries was 70% as of end-2023 based on the ECB’s Consolidated Banking Data, distributed as follows: Croatia 87%, Slovakia 87%, Latvia 86%, Czechia 83%, Bulgaria 73%, Lithuania 70%, Romania 66%, Slovenia 48%, Estonia 46%, Poland 42% and Hungary 36%.

While Chart 1 and 2 below compare CESEE banking sectors with the biggest parent companies, they serve well for illustrational purposes.

As in most of CESEE countries domestic banks are even smaller than the foreign subsidiaries, this higher focus on financing the domestic economy is probably due to the size effect.

Lahnsteiner (2020) notes that most CESEE banking systems have reoriented their funding from net foreign liabilities toward domestic deposits. He argues that this shift increases resilience, although supervisors and policymakers must still address several remaining vulnerabilities. One of his suggestions particularly calls for improving the alignment of funding structures with new regulations through deeper integration of European capital markets. Iwanicz-Drozdowska and Witkowski (2020) show that parent banks first seek geographic diversification of group assets in host countries, then enforce strict capital discipline and aim for subsidiary returns on equity that exceed local market averages. When a subsidiary’s ROE surpasses that benchmark, the parent typically halts further credit expansion and instead maximizes extraction of existing investments. In this way, parent banks are both pushed to find profits beyond their home markets and focused on securing the profitability of their foreign subsidiaries in CESEE countries.

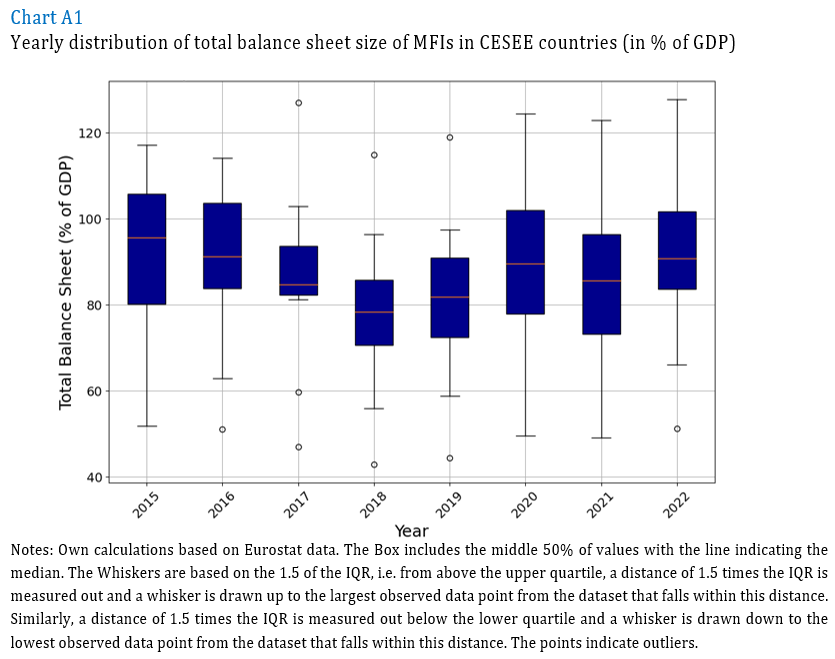

In the appendix in Chart A2, we provide the capital-to-assets ratio, which shows similar patterns.