Basic household safety is a principle embodied in a deposit insurance system deliberately capped to target public safety provision and containing moral hazard.

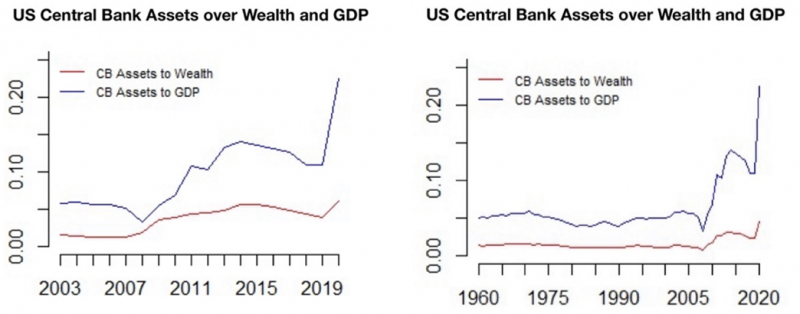

There are concerns that the financial sector become accustomed to abundant liquidity upon rapid expansions of central bank support, such as during the COVID epidemics. Once a policy reversal occurs to contain inflation, banks may struggle during a sustained QT phase to absorb a large stock of demandable promises and credit lines (Acharya ea. 2022). More than ever, assigning liquidity risk to the private sector is essential to contain excess creation of demandable promises.

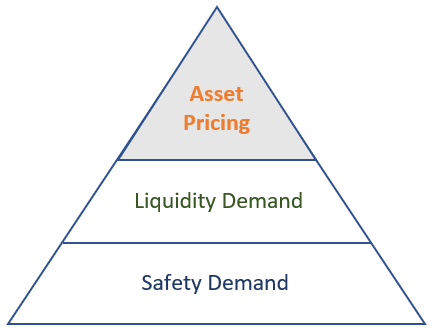

Protecting the safe asset foundation implies a full liquidity backstop to support trading and funding for safe claims, not a mandate to repay.

Once distress starts, the safety border can be ambiguous. As the central bank expands financial safety by easing haircuts on collateral, it implicitly redefines what it is safe.

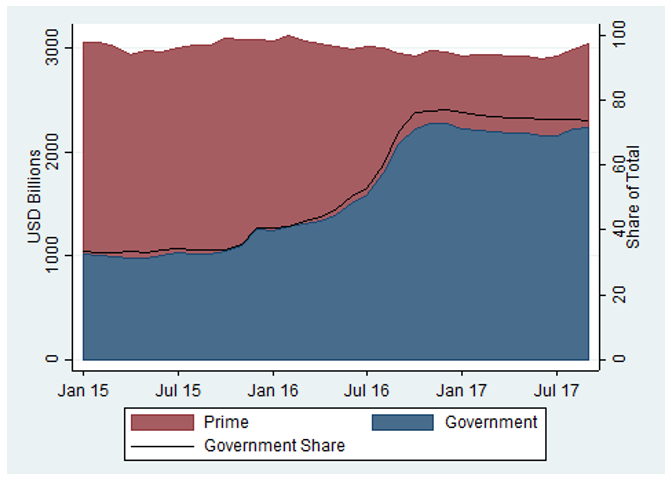

Excess promises of liquidity backed by illiquid assets were vividly denounced by the Bank of England Governor Mark Carney (2019), as a classic warning for shadow banks not to expect support in case of runs.

Reversing large purchase programs, such as the Bank of Japan’s purchase of 80% of the local ETF market or the vast foreign stock holdings accumulated by the Central Bank of Switzerland to contain currency appreciation, create an open ended fiscal exposure with redistributive effects. Programs outside the safe core clearly reflect political priorities (eg economic growth) assigned to the central bank beyond its core function.

Simple benchmarks are unsophisticated but also much harder to game (Shleifer and Glaeser, 2001).

Their result shows how the optimal timing of suspension in general comes after some illiquid assets are sold. However, when intermediaries have discretion on the timing of suspension, the resulting choice is an excessive delay (as the behavior of MMF in March 2022 proved). This insight is consistent with the proposed shift of emphasis on mandatory charges directly activated by large outflows in the proposed MMF regulatory reforms.

In the economic analysis of externalities, runs are driven by fears of dilution, a form of risk externality that may be dealt with by either price or quantity norms (Weitzman 1986, Perotti and Suarez 2011).

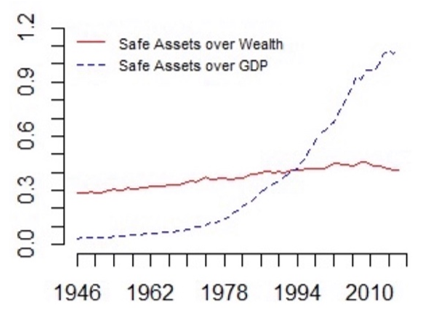

Historical concerns about the inflationary impact of public debt monetization have proven unfounded at times of high demand for safe assets. The massive QE purchase programs adopted by all central banks since 2011 proved successful at supporting demand for safety at a minimal inflationary cost until the COVID shock.