All opinions expressed here in this policy brief are our own and do not necessarily reflect those of Bank of Finland or the Eurosystem.

Abstract

This paper examines the role that price differences within the EU can play in aggregate inflation. To do so, we scrutinize these price differences over time and across commodities, and we attempt to quantify their potential inflationary effects by estimating convergence coefficients with respect to price-level gaps between countries. We find that convergence is a dominating factor, although its role has decreased since the early 2000s. We also find that convergence is asymmetric, reflecting price rigidity, which suggests that it is much stronger when price levels are below the EU average.

In this paper, we examine the contribution of cross-country price-level convergence to overall inflation in Europe. The Balassa-Samuelson theory underpins this convergence: rapid productivity growth leads to increases in wages and prices in the economy’s open or capital-intensive sectors. This results in inflation due to differences in growth rates across sectors, particularly the slow growth in the service sector. Because wages are not indexed to productivity but rather to those in the high-growth sectors, there is continuous pressure to increase prices, which manifests as overall inflation. Thus, high-growth countries experience higher inflation. The story is essentially the same in the Baumol model of public-sector growth: wage growth in the public sector leads to a higher level of public expenditure and to higher taxes

In an open-economy setting, the Balassa-Samuelson theory explains how a country’s real exchange rate is influenced by productivity differentials between its tradable and non-tradable goods sectors. When a country experiences productivity growth in the tradable goods sector, this leads to higher wages across the entire economy. For non-tradable goods (such as services), this results in higher prices, causing overall price increases and real exchange rate appreciation. Although the Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis is well known, European economists typically overlook it in their everyday work, even though irrevocably fixed exchange rates are a fundamental feature of the European Monetary Union.

In the context of inflation analysis, all attention is paid to current output (measured, e.g., by the output gap or the unemployment rate) and current expectations of future price developments. Thus, past developments are deemed irrelevant for future outcomes, and economists focus excessively on short-run developments in the economy, with the maximum time horizon typically being half of the current business cycle.

In a fixed exchange rate regime, this is not an innocent oversight, because if a country (similarly to a firm) prices itself out of the market in real exchange rate terms, it would certainly affect future price and inflation developments. This point is crucially important in a Euro area–type fixed exchange rate system, where cross-border trade is becoming increasingly important. If prices were perfectly flexible and there were no obstacles to trade, we would expect price levels to converge to some sort of average value.

These ideas can be turned on their head to ask whether we can measure the level of integration among Euro area (EA20) countries simply by scrutinizing price-level discrepancies. Such an analysis would also reveal how much the level of integration has deepened over the past 26 years of EMU. Thus, we consider this integration issue alongside our examination of how price disparities affect inflation in different countries and in the Euro area or the entire European Union as a whole. How much inflation is due to this convergence component? In doing so, we pay a great deal of attention to the nature of convergence. The most obvious question concerns the symmetry of convergence—that is, do high-price countries approach the “average level” in the same way (or “speed”) as low-price countries?

Even though the issue of convergence in the EMU context is undoubtedly important, there have been relatively few analyses that focus on it from a macro perspective using price level data. Égert (2010) and Garcia-Hiernaux et al. (2023) represent notable exceptions. However, they do not consider item-level data or changes in weights over time.

We have basic price collection data from EU countries, in addition to constructed (annual) time series and, finally, official monthly HICP data. Needless to say, the basic data presents a significant challenge. The basic “raw” data consists of 23,911 items, comprising 9,457 food items, 6,864 household appliances, and 7,890 service items. The data is far from complete in terms of included commodities, measurements, and sampling years (measurements were taken at three-year intervals). We have also constructed time series indexes using only 276 items for the years 2003–2024 (data for 2008 is missing for some reason). In addition to these annual observations, we have monthly data for 20 Euro countries across 12 commodity groups from 1996M1 to 2025M8. This data is used to assess inflation developments in the Euro area, for instance, by the ECB. This latter dataset also plays a big role in our work as we construct price indexes using the basic price-level data to combine price-level information with the respective change rates.

As for the content of the analysis, we compute values for rebased consumer price indexes, which provide information on inflation rates and, at the same time, the differences between member countries’ price levels and the average level (or other possible benchmark levels). Given this data, we estimate convergence indicators: coefficients of variation and error-correction coefficients for different commodities and countries. Then, we evaluate the properties of these indicators using nonlinear threshold models.

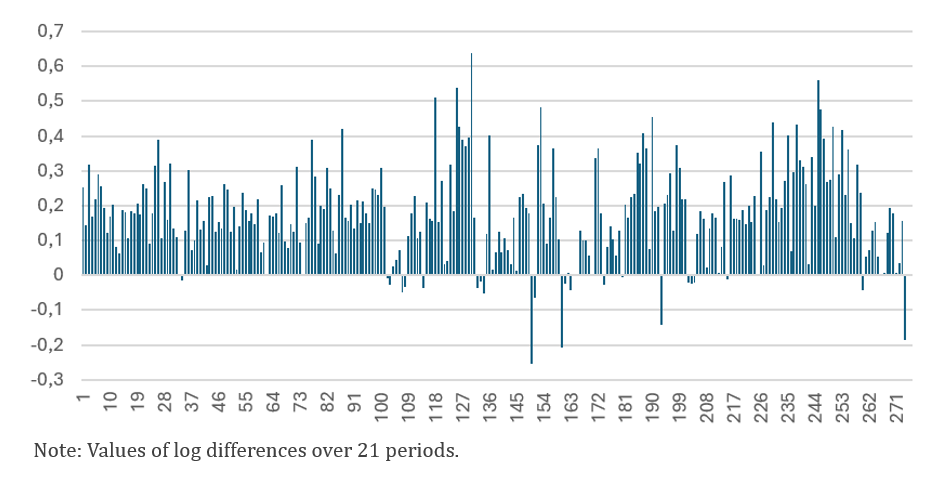

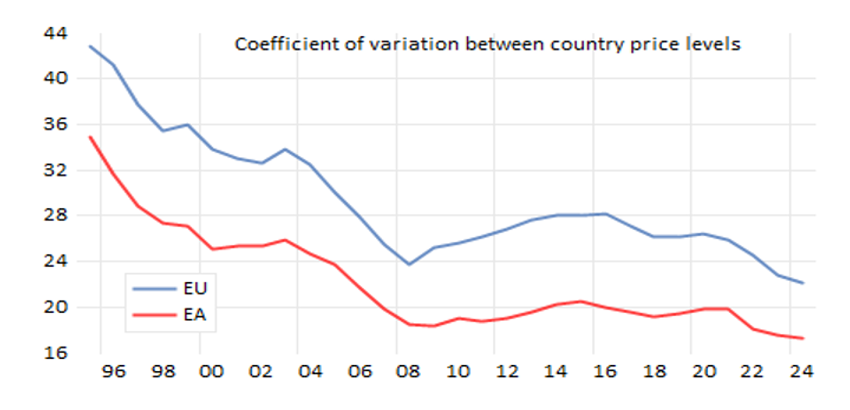

Start with some descriptive data. Figure 1 shows the growth rates of prices for the 276 commodity price-level indexes over the period 2003–2024. Clearly, there is considerable heterogeneity in these growth rates, including even negative values in several cases (probably reflecting items with rapid quality improvements). Even so, we can detect a clear trend in cross-country heterogeneity (see Figure 2). No surprise: dispersion is larger in the EU and in the Euro area. The more interesting point, however, is that dispersion has not markedly decreased after the financial crisis period of 2008/09. From the perspective of integration, this is surely a somewhat disappointing outcome.

Figure 1. Change in price levels for 2003-2024 with 276 commodity groups

Figure 2. Converge of price levels 1995-2024

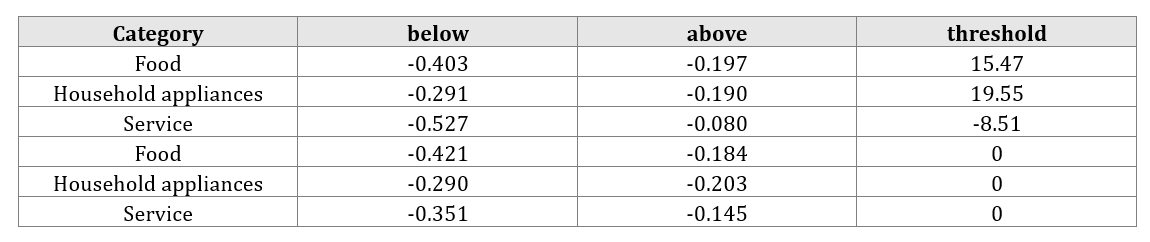

Now, turning to the estimation results, we start with the “raw data” for 2006–2024. Table 1 presents the values, categorized such that the convergence coefficients have been estimated with a threshold allowing the convergence coefficient to differ for large (positive) and small (negative) values. The values represent panel data outcomes for 20 EU countries. In all cases, the coefficients are negative and of reasonable magnitude (given that the sampling period is three years). The message of the results is quite clear: high (relative to the country) prices approach the average values more slowly than negative (below-threshold) values. In other words, prices appear to be sticky downward—a result that is consistent with data from individual countries.

Table 1. Results from the threshold model for the convergence coefficient

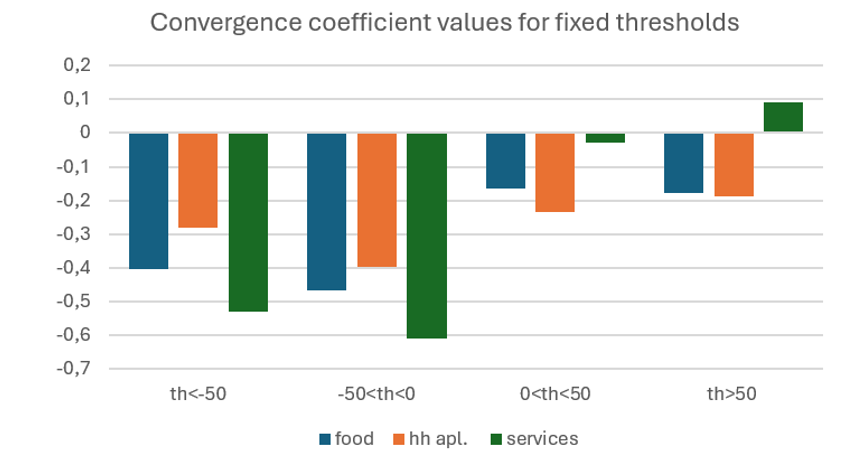

It is only that the convergence pattern appears to be more complex, in the sense that the increase and decrease of coefficient values is not monotonic (see Figure 3). This applies in particular to the lower end of relative prices. Thus, in countries where the price level has been exceptionally low, price-level convergence is not necessarily higher than in countries where prices are closer to the EU average. This probably reflects the fact that in very low price-level countries, markets (and institutions) may function differently. A similar pattern cannot really be detected in high price-level countries.

Figure 3. Converge coefficients for different values of the price level gap

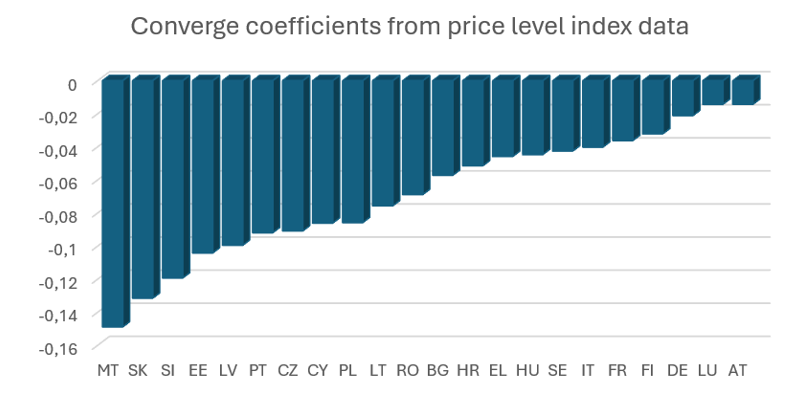

Figure 4 gives the country-specific convergence values estimated from the pooled cross-country data for 22 EU countries over 2003–2024. The estimate for all countries combined is -0.051; in other words, five percent of the price-level gap is eliminated every year on average. Quite clearly, low-income countries have the largest coefficients, while high price-level countries have very small ones (even though the coefficients are statistically significant).

Figure 4. Converge coefficient values

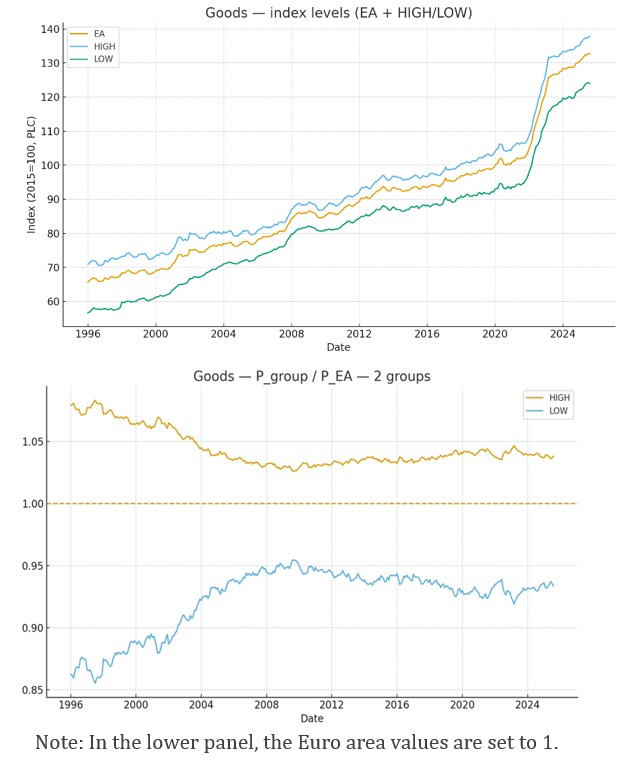

Finally, we give an illustrative example of the price indexes that can be constructed on a monthly basis by using the existing Euro area price index data (Figures 4 and 5). However, instead of assuming the same base values (e.g., 2015=100) for all countries, we have computed the indexes by allowing for the price level of each country and commodity group be determined by the “true” market prices expressed in Euros. We have selected two groups of countries on the basis of their position in 1996, so that “low” (“high”) denotes countries below (above) the average value. In absolute terms, the gap between these groups appears to be almost constant, but in relative terms there has been marked convergence, even though it has been far from monotonic. Here we just show the indexes for the aggregate index of goods but the same pattern can be detected with other commodity groups as well.

Figure 5. Rebased price index of goods, actual and rescaled values

Convergence is the dominant feature across all countries. There are signs of asymmetry in convergence, reflecting downward price rigidity: it is “easier” to increase prices than to decrease them. Moreover, increased price-level dispersion implies a higher rate of convergence. However, there is considerable heterogeneity in country-specific results, as well as in estimates for different time periods—generally indicating strong convergence in the early 2000s, followed by a standstill and then renewed momentum during the high-inflation period of 2021–2023. The fact that convergence is important forces us to reconsider models of inflation in which past price-level developments play no role in current price setting. Instead, the idea of a more state-dependent view appears more appealing (cf., e.g., Golosov and Lucas 2007). The accession of new members to the EU/EA is not the only case in which state-dependent pricing is relevant. There may well be failures, e.g., in income policies or the functioning of markets, which will later come back to haunt the possibilities for price setting.

Egert, B. (2010) Catching-up and inflation in Europe: Balassa-Samuelson, Engel’s law and other culprits. OECD Economics department Working papers no. 792

Garcia-Hiernaux, M. Gonzales-Perez and D. Guerrero (2023) Eurozone prices: A tale of converge and divergence. Economic Modelling 126, 1-20.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264999323002304

Golosov, M. and R. E. Lucas, Jr. (2007) Menu Costs and Phillips Curves”, Journal of Political economy, 115 (2) 171–199.