This policy brief is based on “Political polarization in Europe”, Banco de España Working Paper No. 2533, September 2025, by Marina Diakonova, Corinna Ghirelli, and Javier J. Pérez. All data and quotations are drawn from that study. The views expressed here are those of the authors of the original paper and do not necessarily represent the Banco de España or SUERF.

Abstract

This study introduces two high-frequency indices—the Political Polarization Index (PPI) and Legislative Gridlock Index (LGI)—to track partisan conflict and policy stalemates across France, Germany, Spain, and Italy using news media analysis. Results show that while polarization has increased sharply since the late 2000s, its consequences for legislative gridlock vary: polarization and gridlock move in tandem in France and Germany, but diverge in Spain and Italy, where institutional reforms have shaped outcomes. These findings highlight that the impact of polarization on governance depends on political structures. By separately monitoring polarization and gridlock, policymakers can better anticipate risks and design reforms to safeguard effective governance.

Political polarization—the growing ideological gap between parties and their supporters—has become a defining challenge for European democracies. When partisan rifts deepen, governments may find it harder to build consensus, risking legislative gridlock that stalls reforms and complicates policymaking. For economists, the stakes are high: polarization can undermine fiscal discipline, fuel policy reversals, and generate economic uncertainty as businesses and households delay investment decisions amid unpredictable political climates. Yet, the link between polarization and its institutional consequences is far from straightforward.

Recent research by Diakonova, Ghirelli, and Pérez (2025) introduces a fresh approach to this debate, separating the measurement of political polarization from legislative gridlock across France, Germany, Spain, and Italy. Using high-frequency media analysis, they construct two new indices—the Political Polarization Index (PPI) and the Legislative Gridlock Index (LGI)—to track shifts in partisan conflict and policy stalemates over the past two decades. This method allows for a clearer view of when and how polarization matters for economic and political stability, equipping policymakers and economists with sharper tools to anticipate dysfunction and design resilient institutions.

This study applies a straightforward, text-based approach to monitor changes in political polarization and legislative gridlock on a monthly basis, providing policymakers and analysts with up-to-date indicators of partisan conflict and policy stalemate. Using the Dow Jones Factiva archive, the analysis examines articles from major national newspapers in France, Germany, Spain, and Italy—including Le Monde, Le Figaro, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Die Welt, El País, El Mundo, Corriere della Sera, and La Repubblica. By processing a large number of news reports, the researchers generate two country-specific time series: one that measures references to partisan division and another that captures mentions of legislative deadlock.

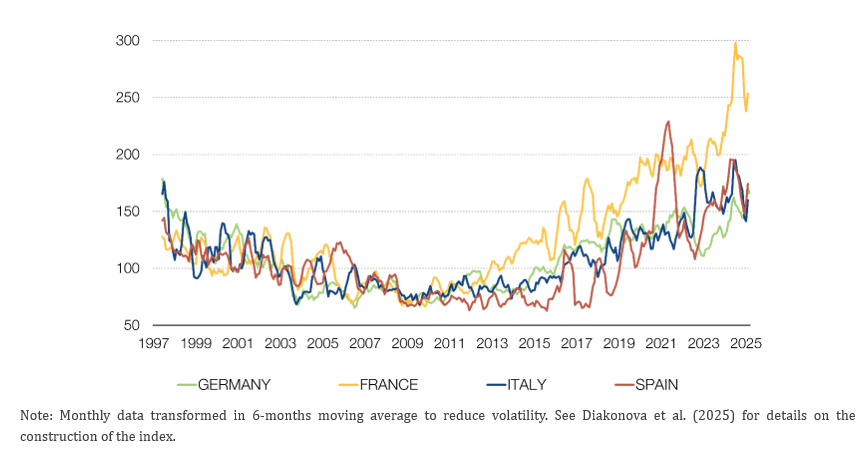

To build the Political Polarization Index (PPI), the team counts articles that feature not only explicit markers of ideological conflict—terms like “polarization” or “ideological division”,—but also references to political actors and institutions such as “government”, “parliament”, “party”, or “policy” (see Fig.1).

Figure 1. Political Polarization Index

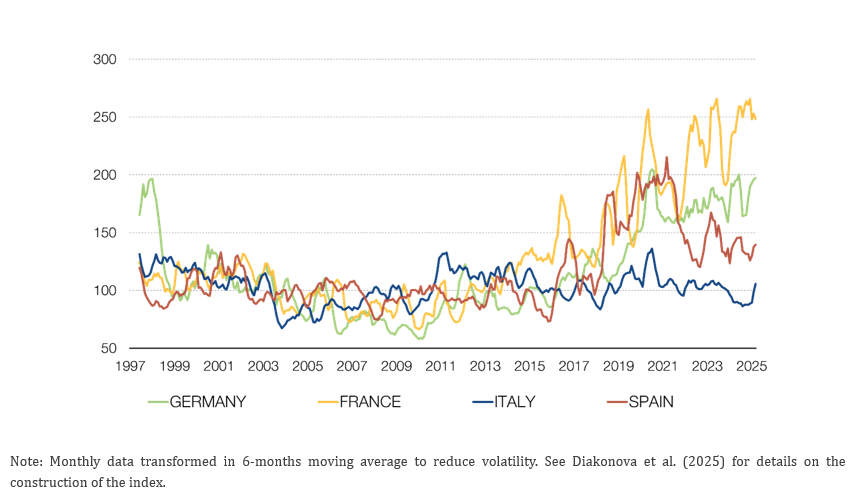

This dual filter ensures the index reflects genuine partisan rifts within the political arena, rather than capturing generic social discord. Meanwhile, the Legislative Gridlock Index (LGI) applies a similar approach, zeroing in on articles that spotlight stalled policymaking—phrases like “legislative impasse”, “policy deadlock,” “stalemate”, or “blocked reform”—again, in the context of government and political processes. Only when the reporting describes the government or parliament as paralyzed (due to, for example, failed votes, blocked budgets, collapsed coalitions, or emergency decrees invoked to bypass normal procedures) does it count towards the LGI (see Fig.2). Furthermore, the authors require that the relevant articles for both indices focus on domestic matters, in order to minimise signal coming from polarization in other countries.

Figure 2. Legislative Gridlock Index

Both indices are normalized by the total volume of news for each country and month, which allows the analysis to gauge the prominence of polarization or gridlock relative to the overall news cycle. This adjustment levels the playing field for comparing different countries and time periods: a score of 150 in the PPI, for instance, means that polarization-related coverage is running 50% above the national monthly average during the 1997–2009 baseline (which is set to 100). This normalization is crucial for tracking trends across the diverse environments of national media, each with its own idiosyncratic characteristics.

To ensure the indices mirror real-world developments, researchers cross-validate spikes against historical events. Whenever the PPI or LGI jumps, they review headlines and stories to pinpoint the catalyst—be it a heated debate around a reform, a snap election, or a coalition collapse. This narrative crosscheck confirms that spikes in the indices are tightly aligned with periods of genuine partisan confrontation and institutional stalemate and are not merely random noise. Peaks in the PPI consistently coincide with major political flare-ups, while LGI surges map to episodes of legislative paralysis.

This approach stands out for its immediacy and comparability. Unlike traditional measures based on elections or surveys, these indices offer high-frequency, up-to-date insights, capturing sudden swings—such as a spike in polarization during a fractious budget debate or a burst of gridlock talk after a hung parliament—without the lag of electoral cycles or annual polls. Moreover, by applying a uniform method across languages and institutional settings, the study delivers a cross-country perspective that has long been missing from the literature, which has tended to focus on single countries such as the United States. The result: a robust set of tools to monitor and compare partisan conflict and policy stalemate across Europe, empowering policymakers and researchers to anticipate risks and design responses with new precision.

Since the late 2000s, political polarization has surged across Europe, a trend that closely follows the fallout from the Global Financial Crisis and the subsequent sovereign debt turmoil. While polarization was relatively subdued in the early 2000s, all four countries in the study—France, Germany, Spain, and Italy—saw a marked increase afterward, with the PPI showing both gradual rises and sharp event-driven spikes. This broad pattern underscores how economic shocks and emerging political challenges, such as the eurozone crisis, migration waves, and the rise of populist movements, have tested political consensus and deepened partisan divides.

The relationship between polarization and legislative gridlock, however, varies significantly across countries. In France and Germany, periods of heightened polarization almost invariably coincide with higher values of legislative deadlock, validating concerns that deeper ideological rifts can paralyze policymaking. For instance, mass protests and partisan clashes in France, as well as coalition formation hurdles and divisive policy debates in Germany, have translated into real difficulties in passing legislation and sustaining consensus.

By contrast, Spain and Italy present a more nuanced picture. Although both experienced rising polarization, the impact on gridlock was shaped by their institutional structures. Spain’s political fragmentation led to challenges in government formation and the occasional gridlock, particularly amid new party emergence and regional tensions. Yet, even during intense crises like the Catalan standoff, the major political parties sometimes found common ground sufficient to avoid prolonged paralysis. In Italy, polarization intensified with the rise of new parties, but electoral reforms and a flexible coalition system helped insulate legislature from political turmoil. Frequent government changes occurred, but outright gridlock was often averted by the system’s capacity to produce workable majorities or caretaker administrations.

These findings indicate that while rising polarization is a common European trend, it has not necessarily been accompanied by more political gridlock in all the countries in our study. Institutional design—electoral rules, parliamentary practices, and coalition mechanisms—plays a decisive role in determining whether partisan divides lead to policy paralysis or whether they can be managed within functioning democratic frameworks.

From an economic policy perspective, both the PPI and the LGI provide timely indicators of political risk, serving as early warning signals for potential delays in fiscal measures or rising policy uncertainty. Integrating these indices into risk assessments can enhance policymakers’ ability to respond to evolving political conditions.

The increase in political polarization across Europe, as tracked by the PPI, has significant consequences for economic governance and policy implementation. Importantly, our research finds that heightened polarization does not necessarily go hand in hand with legislative gridlock; the relationship depends on the unique institutional framework and political traditions of each country. In France and Germany, the strong connection between polarization and gridlock highlights the need for policymakers to proactively address the risks posed by extreme partisanship. Strategies such as cross-party agreements, coalition arrangements, and procedural innovations can help maintain legislative productivity. For example, Germany’s broad coalitions and France’s use of constitutional measures like Article 49.3 have ensured continuity of governance, though sometimes at the expense of consensus or democratic norms. These experiences suggest that reforms geared toward promoting compromise—such as changes in electoral or parliamentary rules—are valuable in highly polarized environments.

Spain’s transition to a more fragmented party system brought new challenges, including increased polarization and shorter government lifespans, but showed that persistent gridlock can be avoided if major parties collaborate on critical issues. It would seem that mechanisms to streamline government formation and encourage dialogue, as well as clear constitutional processes for managing regional disputes, can help prevent systemic paralysis. Italy demonstrates that even in a turbulent political setting, electoral reforms can foster workable majorities and minimize persistent gridlock, offering a model for countries facing similar challenges. Italy shows that institutions matter: despite becoming more polarized, it did not suffer the same political gridlock as other countries. Italian polarization increased significantly over the past decade, yet the country did not experience prolonged legislative deadlock. We speculate that that is because internal electoral reforms brought greater stability to Italy’s political system, enabling the formation of stronger governing majorities. As a result, Italy maintained governability even amid high polarization—unlike Spain, where parliamentary fragmentation after the 2018 general elections led to a period of failed investiture attempts and fragile coalitions and minority governments.

Overall, the varied experiences of France, Germany, Spain, and Italy underline that increased polarization does not inevitably lead to governance breakdown. Instead, targeted policy actions and institutional adaptation can help maintain democratic functionality and public trust, even during periods of intense disagreement.

In summary, while political polarization has risen across Europe, its effects on governance depend on institutional design and the legislature’s flexibility. The study shows that with proactive reforms and consensus-building, democracies can remain functional and resilient in the face of division. Using tools like the PPI and LGI, policymakers are better equipped to anticipate risks and tailor responses to their country’s specific challenges.