This policy brief is based on IMF Working Papers, Volume 2025: Issue 171. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

Cross-border payments are changing. Existing intermediaries are upgrading their networks and new platforms based on novel digital forms of money are being explored, even as geoeconomic fragmentation is introducing new frictions. We develop a stylized model to assess the potential implications for the level and volatility of capital flows and exchange rates. On levels, we find that lower frictions in cross-border payments reduce UIP deviations and increase capital flows. On volatility, we find that the impact of lower frictions depends on the type of shock and the degree to which frictions decline. For real shocks, lower frictions increase capital flow volatility and reduce exchange rate volatility. For financial shocks, lower frictions increase exchange rate volatility while the impact on capital flow volatility is ambiguous. Specifically, when frictions decline by a small amount, capital flow volatility increases, while the opposite holds when the reduction in frictions is large. An increase in frictions reverses these results.

Cross-border payments are evolving quickly amid technological and policy shifts. Many initiatives are underway to upgrade established infrastructures (CPMI, 2024; FSB, 2024) or introduce new rails for cross-border payments (such as central bank digital currencies and stablecoins). At the same time, geopolitical tensions risk erecting new barriers between some countries (IMF, 2023; WEF, 2025), potentially amplifying cross-border payment frictions (Eichengreen, 2022).

Understanding how changes in cross-border payment frictions affect capital flows and exchange rates is particularly important for policymakers. In emerging and developing economies, volatile capital flows have often been a source of financial instability, and exchange rate swings have at times amplified such vulnerabilities (Goldberg and Cetorelli, 2011; Laeven and Valencia, 2020).

In a new IMF Working Paper, we provide a framework to analyze this important question. Our model (which builds on Gabaix and Maggiori (2015) and Kekre and Lenel (2024)) features two economies where financial institutions intermediate household savings, enabling current and capital account imbalances. The model thus captures the key role that financial intermediaries play in facilitating cross-border payments.

Intermediaries face both fixed and variable costs when conducting cross-border transactions. Such costs represent payment frictions—for example, fees, settlement delays, and limited connectivity—which produce deviations from Uncovered Interest Parity (UIP). Each intermediary weighs the potential profits from investing abroad against the risks created by currency fluctuations and the costs of making cross-border payments. Some intermediaries are more risk-tolerant than others, so their participation depends on whether expected returns outweigh both the risks and the costs.

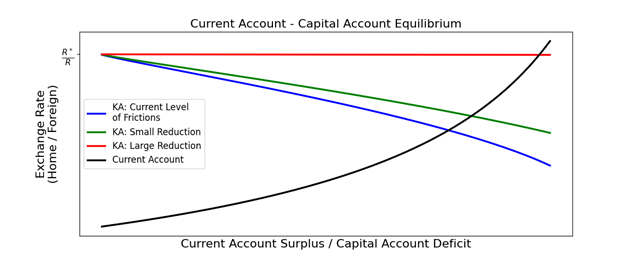

The capital account reflects the aggregate intermediation decisions of all intermediaries whose costs are sufficiently low that they are outweighed by the expected risk-adjusted profits from intermediation. These profits, in turn, result from UIP deviations, on which the intermediaries can capitalize. The capital account thus has the same sign as the UIP deviation: a capital account deficit is associated with a UIP deviation in favor of the foreign currency, while a capital account surplus implies a UIP deviation in favor of the domestic currency. In turn, the equilibrium exchange rate is that which brings the current account and capital account into balance.

Reducing payment frictions increases capital flows. Lower fixed costs allow more intermediaries to enter the market and lower variable costs increase the quantity of intermediation that each chooses to provide. Together, these forces increase total intermediation for any given UIP deviation, leading to greater capital mobility. In graphical terms, a reduction in frictions flattens the capital account curve, indicating that capital flows become more responsive to differences in expected returns.

Figure 1. Capital Flows, Exchange Rates, and Reductions in Payment Frictions

Source: Reuter et al. (2025). This figure shows the current account and capital account balances as a function of the exchange rate, with an initial level of frictions and after frictions are reduced.

The effect of lower payment frictions on volatility depends on the type of shock hitting the economy:

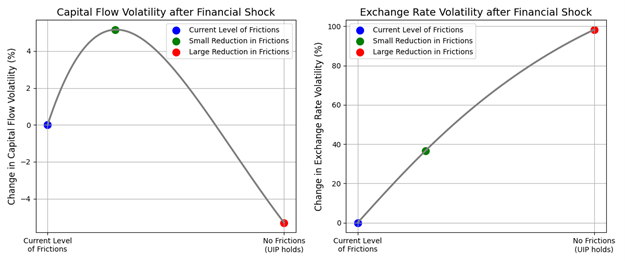

In the case of financial shocks — such as changes in global interest rates or risk appetite — lower frictions increase exchange rate volatility and have ambiguous effects on capital flow volatility. This result reflects the interaction between two opposing forces. As frictions decline, the capital account becomes more responsive to shocks. At the same time, lower frictions alter the equilibrium between the current and capital accounts. The resulting expansion of cross-border intermediation increases external imbalances and leads to an equilibrium at a point where the current account is steeper. Consequently, a larger share of the adjustment to shocks occurs through exchange rate movements rather than through capital flows. This second effect raises exchange rate volatility but dampens capital flow volatility. Taken together, these forces imply that exchange rate volatility rises unambiguously when payment frictions decline, while the effect on capital flow volatility depends on which of the two dominates. When the reduction in frictions is small, the amplification effect prevails and capital flow volatility increases. When frictions fall significantly, the adjustment effect becomes stronger, leading to lower capital flow volatility as the economy moves toward the steeper part of the current account curve.

Figure 2. Capital Flows and Exchange Rate Volatility in Response to a Financial Schock

Source: Reuter et al (2025). This figure shows how capital flow and exchange rate volatility following a financial shock change as the level of frictions is reduced from a benchmark level. Given the stylized nature of our model, the values on the vertical axes should be considered illustrative rather than quantitative.

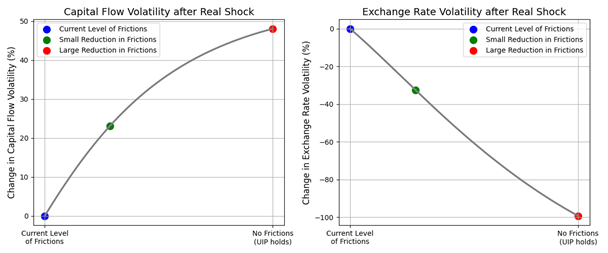

For an economy facing real shocks—such as changes in productivity or the terms of trade—lower frictions increase capital flow volatility but reduce exchange rate volatility. Real shocks cause shifts in the current account. How these shifts translate into movements in capital flows and exchange rates depends on the slope of the capital account, which in turn reflects the frictions faced by financial intermediaries. When frictions are lower, intermediaries can respond more easily to changes in the exchange rate, expanding aggregate intermediation capacity. As a result, the capital account becomes flatter, meaning that a given shock to the current account is absorbed more through capital flows and less through movements in the exchange rate.

Figure 3. Capital Flows and Exchange Rate Volatility in Response to a Real Schock

Source: Reuter et al (2025). This figure shows how capital flow and exchange rate volatility following a real shock change as the level of frictions is reduced from a benchmark level. Given the stylized nature of our model, the values on the vertical axes should be considered illustrative rather than quantitative.

Against the backdrop of a rapidly changing landscape in cross-border payments, we provide a framework to examine how changes in payment frictions could influence both the level and volatility of capital flows and exchange rates.

Reduced frictions unambiguously lead to increased capital flows. The impact of frictions on volatility depends on the type of shock and the direction and magnitude of the change. Lower frictions increase capital flow volatility in response to real shocks while decreasing exchange rate volatility. Conversely, for financial shocks, lower frictions increase exchange rate volatility and have an ambiguous effect on capital flow volatility.

Policymakers could combine our framework with knowledge of countries’ characteristics to identify the most likely implications in their contexts. By preparing for such potential outcomes, policymakers could better navigate the evolving landscape of cross-border payments and mitigate the risks associated with changes in the level and volatility of capital flows and exchange rates.

CPMI (2024). “Linking Fast Payment Systems Across Borders: Governance and Oversight – Final Report,” Tech. rep., Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures, Bank for International Settlements.

Eichengreen, B. (2022): “Sanctions, SWIFT, and China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payments System,” CSIS Briefs.

FSB (2024): “Annual Progress Report on Meeting the Targets for Cross-border Payments: 2024 Report on Key Performance Indicators,” Tech. rep., Financial Stability Board.

Gabaix, X. and M. Maggiori (2015): “International Liquidity and Exchange Rate Dynamics.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130, 1369–1420.

Goldberg, L. and N. Cetorelli (2011): “Global Banks and International Shock Transmission: Evidence from the Crisis,” IMF Economic Review, 59, 41–76.

IMF (2023): “Geopolitics and Financial Fragmentation,” Global Financial Stability Report, Chapter 3, International Monetary Fund.

Kekre, R. and M. Lenel (2024): “Exchange Rates, Natural Rates, and the Price of Risk,” NBER WP 32976, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Laeven, L. and F. Valencia (2020): “Systemic Banking Crises Database II,” IMF Economic Review, 68, 307–361.

Reuter, M., I. Agur, A. Copestake, M.S. Martinez Peria, and K. Teoh: “Payment Frictions, Capital Flows, and Exchange Rates,” IMF Working Paper 2025/171.

WEF (2025): “Navigating Global Financial System Fragmentation,” Tech. rep., World Economic Forum.