This Policy Brief summarises the main insights from my report “Overcoming myopia in the ECB’s 2025 monetary policy strategy review” (2025, EMPN & Dezernat Zukunft, Berlin).

Executive Summary

The European Central Bank (ECB)’s monetary policy strategy specifies its price stability objective and how it goes about achieving it. Since starting operations in 1998, the ECB has reviewed that strategy and made minor changes in 2003 and 2021. A new review is set to be finalised this summer. What lessons should the ECB draw from the dramatic experience of inflation of the past years, the first major inflationary episode since the 1970s?

This Policy Brief argues that the ECB’s current monetary policy strategy is unduly myopic. It focus on medium-term inflation expectations, which reflects the inflation of the 1970s. The strategy’s narrow focus led the central bank to miss the build-up of long term, structural risks – brittle supply chains, energy dependence, changes in competition and pricing behaviour.

In its review the ECB should adopt a long-term interpretation of its price stability objective. It should also introduce a dedicated analytical pillar that covers the economic preconditions of price stability, paying special attention to topics such as geopolitical risks, climate and energy, market power, and supply chain resilience. Finally, the ECB should position monetary policy within a broader EU inflation policy framework and be more precise about where other policymakers have more appropriate tools to prevent or absorb shocks.

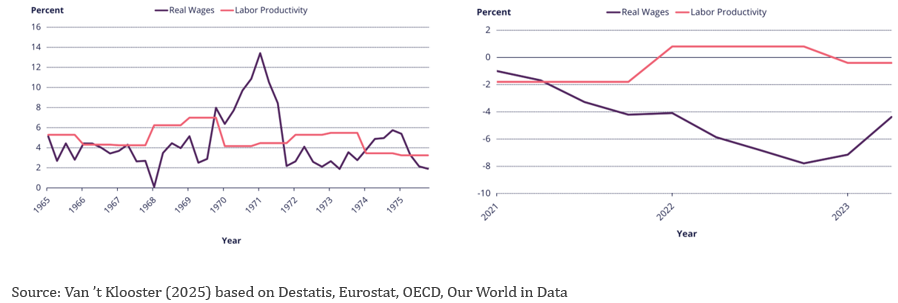

The ECB’s current strategy is shaped by the historical experience of the 1970s, when the German Bundesbank successfully used monetary policy measures to subdue inflation resulting from the First Oil Crisis (von Hagen, 1999). This strategy worked well to stop inflation that originated in double-digit wage growth, and rapidly increasing government spending (Hall, 1994, p. 199). At the time, wages and government spending were out of whack already before the cost shock of the 1973 oil crisis (Figure 1). By credibly committing to bring down economy-wide demand through its interest rate instrument, the German Bundesbank shifted inflation expectations. This stopped the ongoing wage-price spiral.

Figure 1. Year-over-Year Change in Real Wages vs. Labor Productivity During Two Inflationary Periods. Real wages are calculated as the hourly wage rate in manufacturing minus CPI inflation. Labor productivity is defined as GDP divided by total hours worked

The experience of the 1970s continues to profoundly shape how central banks define their inflation-fighting task. It informs the view that demand-side drivers are the main risk to price stability. Via a credible commitment to act in response to excessive wage increases and government spending, the ECB seeks to “anchor” society-wide inflation expectations. This strategy served the central bank well until recently. During the Great Moderation, interest rate policy was more than enough to keep inflation low and stable.

In the post-pandemic inflation, however, the monetary policy strategy misdirected the ECB’s attention. The inflation had new, previously neglected drivers (Hansen et al., 2023; Weber and Wasner, 2023; Dao et al., 2024). First, supply constraints and food and energy shocks hiked key input prices in a few specific sectors (BIS, 2022). In this context, firms were well-positioned to raise their prices. Knowing that their competitors faced the same shocks, they felt they could pass on the cost shock by hiking prices. In a recent study (Weber, et al., 2024), we study what corporate executives said about cost shocks in presenting quarterly earnings reports to investors between 2007 and 2022. Using sentiment analysis through both dictionary-based natural language processing and a large language model approach, we show that large cost shocks (as well as their co-occurrence with supply constraints) correlates with positive sentiments expressed in executives’ statements about cost increases. Corporate executives explain that because they knew that their competitors would raise their prices synchronously they could do the same without fear of losing market share. In stark contrast to the 1970s, real wages declined (See Figure 1).

The new drivers of inflation largely fell outside the ECB’s analytical framework, newly revised in 2021, which has two pillars. An economic pillar covers potential drivers of inflation, all of which relate to decision-making on the short or medium-term monetary policy stance to ensure well-anchored expectations (ECB, 2021, p. 13):

As a consequence, the strategy pays little attention to anticipating potential future drivers and understanding the structural causes of, or (potential) risks to, price stability. In the earlier 2003 strategy, a monetary pillar focused on the analysis of monetary aggregates for the purpose of identifying long-term risks to price stability. The 2021 review replaced this pillar with a monetary-financial pillar focused on the transmission of monetary policy.

While central bank research departments were relatively quick to identify both costs shocks and firm pricing strategies as important drivers (Schnabel, 2022), this did not translate into a rethinking of inflation governance (Goutsmedt and Fontan, 2024). In line with the 2021 strategy, the governing council initially took the view that the inflationary effect of supply shocks could be transient and required only a modest policy response (e.g. ECB, 2022). While the central bank waited, inflation struck hardest at low-income households, and real wages declined steeply. In the years that followed, incumbent governments lost their election as voters often turned to authoritarian parties.

Four lessons from the post-pandemic inflation

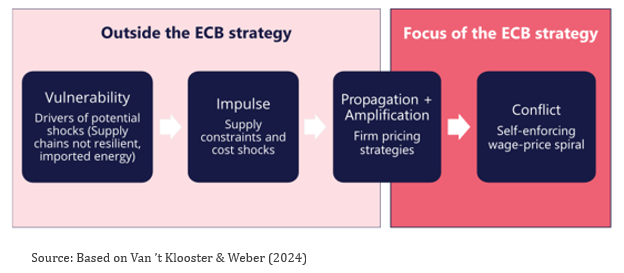

The ECB’s strategy, accordingly, led it to miss the build-up of these risks, while spending precious time looking for signs of an incipient wage-price spiral (See Figure 2). Going forward, every effort should go towards preventing another round of inflation, which may again have new drivers – climate and environmental crises, demographic pressures from an aging workforce, rearmament, trade conflicts, or geopolitical shocks including war.

Figure 2. The ECB’s strategy only made new drivers a concern for the central bank once inflation was already well under way

Four lessons are crucial for the ongoing review of the ECB’s monetary policy strategy.

First, the strategy should assign a more prominent role to the preparation and anticipation of new shocks. It became clear that even if monetary policy measures bring the economy closer to the 2% target, the economy can at the same time get more vulnerable to future inflationary or deflationary shocks. For example, supply constraints built up over the years preceding 2022 as firms increasingly relied on longer value chains and just in time production. These developments reflect a specific market failure, where upstream sectors in which firms underinvest in capacity see their market power increase (Capponi et al., 2024). A too narrow focus on the medium term can undermine long-term price stability.

Second, conventional monetary policy is not always an adequate tool to respond to an inflationary environment, even if it has an important demand component. Ex-ante well-anchored inflation expectations ameliorated the inflationary surge, but were ultimately not a sufficient bulwark against inflation, in particular as amplified by firm pricing strategies. Firms are relatively insensitive to expected inflation. Rather they look first and foremost to their cost structure and what competitors do. Firms can rapidly change prices in response to surprise cost developments, while central banks lack instruments to directly shape their pricing behaviour. This is different from wage bargaining or fiscal policy, which involves coordination and takes into account the expected central bank reaction.

A third lesson to draw from the post-pandemic experience is that the central bank cannot always simply wait for shocks to happen and see through them. Letting major inflationary waves ripple through the economy had a dramatic impact on households’ cost of living , with real wages declining at 5.1% year-on year at the peak of inflation in the third quarter of 2022 (EC, 2024). While wages did go up that year, this only compensated around 20% of the cost shock (Adolfsen et al., 2024) (see Figure 1).

Finally, however, using conventional monetary policy tools can also have important downsides from the perspective of long-term price stability. High rates create an additional shock to households with flexible mortgage payments. Curbing demand via interest rate increases can also undermine long-term price stability by increasing the cost of crucial investments, particularly in clean energy. A myopic approach can make the EU economy more vulnerable to future inflationary shocks.

In sum, facing new shocks, the optimal policy is often neither to hike aggressively nor to do nothing; it is to avert such situations in the first place. This, however, requires a conception of price stability that is not limited to a medium-term time horizon.

A new, forward-looking strategy should recognise the structural preconditions of price stability, and coordinating more effectively with other EU-level tools. The ECB should do three things.

First, change concerns the objectives of the strategy. The ECB should broaden the time horizon of its strategy to make the long-term preconditions of price stability themselves part of the price stability objective. Contrary to common belief, the ECB mandate does not prescribe an account of what price stability is or how to pursue it. In 1990, the drafters of the mandate deliberately left the monetary policy strategy open, allowing it to “respond adequately to changing market conditions” (CoG, 1990, p. 16). The ECB’s objective is “price stability” without qualification, which clearly requires keeping an eye on latent long-term drivers. The medium-term orientation is too narrow.

Second, to ensure adequate study of these topics in Governing Council deliberations, the ECB should expand its analytic framework with a third pillar focused on long term price stability. This pillar should cover:

Finally, The EU’s current governance framework assigns a key role to the ECB’s monetary policy in preventing inflation. For a wide range of shocks, this neither addresses their root causes nor does it effectively deal with the negative economic and social effects of inflation. The optimal policy is neither to react nor to do nothing; it is averting such situations in the first place, which, however, the central bank cannot do alone.

Effectively dealing with inflation, therefore, is impossible without supporting measures from other EU-level policymakers (van ’t Klooster and Weber, 2024). The ECB should accept that it lacks a simple button to bring down inflation. While strictly safeguarding its independence, the ECB should look into ways to embed monetary policy in a broader EU inflation-fighting framework that enables strategic coordination with fiscal, industrial, and competition policies.

Adolfsen, J.F., Ferrari Minesso, M., Mork, J.E., Van Robays, I., 2024. Gas price shocks and euro area inflation (Working Paper Series No. 2905). European Central Bank.

BIS, 2022. Annual Economic Report. Bank for International Settlements, Basel.

Capponi, A., Du, C., Stiglitz, J.E., 2024. Are Supply Networks Efficiently Resilient? (Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2024-031). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington.

CoG, 1990. Draft statutes of the European System of Central Banks and the European Central Bank with an introductory report and a commentary. Europe Agence, Brussels.

Dao, M.C., Gourinchas, P.-O., Leigh, D., Mishra, P., 2024. Understanding the international rise and fall of inflation since 2020. Journal of Monetary Economics 103658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2024.103658

EC, 2024. Labour market and wage developments in Europe – Annual review 2023. European Commission, Brussels.

ECB, 2022. Monetary policy statement (with Q&A).

ECB, 2021. An overview of the ECB’s monetary policy strategy. European Central Bank, Frankfurt.

Goutsmedt, A., Fontan, C., 2024. The ECB and the inflation monsters: strategic framing and the responsibility imperative (1998–2023). Journal of European Public Policy 31, 999–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2281583

Hall, P., 1994. Central Bank Independence and Coordinated Wage Bargaining: Their Interaction in Germany and Europe. German Politics & Society 1–23.

Hansen, N.-J., Toscani, F., Zhou, J., 2023. Euro Area Inflation After the Pandemic and Energy Shock: Import Prices, Profits and Wages. International Monetary Fund.

Schnabel, I., 2022. The globalisation of inflation.

van ’t Klooster, J., 2025. Overcoming myopia in the ECB’s 2025 monetary policy strategy review. EMPN & Dezernat Zukunft, Berlin.

van ’t Klooster, J., Weber, I.M., 2024. The EU’s inflation governance gap: The limits of monetary policy and the case for a new shockflation toolbox (Study requested by the ECON Committee). European Parliament, Brussels.

von Hagen, J., 1999. Money growth targeting by the Bundesbank. Journal of Monetary Economics 43, 681–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(99)00009-4

Weber, I.M., Wasner, E., 2023. Sellers’ inflation, profits and conflict: why can large firms hike prices in an emergency? Review of Keynesian Economics 11, 183–213. https://doi.org/10.4337/roke.2023.02.05

Weber, I.M., Wasner, E., Lang, M., Braun, B., Van ’t Klooster, J., 2024. Implicit Coordination in Sellers’ Inflation: How Cost Shocks Facilitate Price Hikes (No. Manuscript).