This policy brief is based on NBER Working Paper 34114. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

Intermediate inputs are central to production costs and consumer prices, making their pricing a critical policy concern. This study makes two contributions. First, it links aggregate input markups to both exporter and importer concentration, showing how oligopoly and oligopsony power interact in global supply chains. Second, it develops network-based concentration measures that adapt traditional indices to reflect the rigidity of buyer–supplier links. Using Colombian import data from 2011–2020, we document rising exporter concentration alongside stable importer concentration. Our framework interprets these trends as evidence of rising markups, driven primarily by exporters’ market power. By contrast, conventional approaches that proxy markups with industry-wide seller concentration misrepresent these dynamics. By explicitly incorporating two-sided market power and the rigidity of trading relationships, our approach offers a more accurate and policy-relevant measure of markups in firm-to-firm trade, while preserving the tractability of standard concentration analysis.

The expansion of global supply chains (GSCs) has placed intermediate inputs at the center of economic activity. From car parts to semiconductors, they make up a significant portion of international trade and production costs, especially in manufacturing and goods-producing sectors. Markets for intermediate goods often function as bilateral oligopolies, where a small number of large exporters and importers repeatedly negotiate prices in environments marked by high entry and switching costs (Antràs, 2015). Such dominance by a few global firms raises questions about the evolution of market power in input trade.

Measuring market power is notoriously difficult. Markups—the difference between prices and costs—are not directly observable, so economists and policymakers often use concentration indices as proxies. The logic comes from standard Cournot oligopoly theory: when sellers are more concentrated and face price-taking buyers, they gain greater ability to raise prices. This reasoning underpins much of merger review and antitrust analysis, where industry-level HHIs are widely used to assess competition.1

Firm-to-firm trade, however, departs from this textbook setting in two important ways. First, importers are far from passive: large buyers can exert oligopsony power and push prices down. Second, standard concentration indices like the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) rely on the assumption that buyers and suppliers can switch trade partners freely. In reality, establishing a trading relationship is costly, and switching is uncommon, with firm-to-firm trade taking place within sparse and stable buyer–supplier links.2

Our study (Alviarez et al., 2025b) tackles both these challenges by offering a theoretical and empirical framework for when and how concentration measures can inform about pricing power in global supply chains.

Our first contribution is to show that overall input markups can be expressed as a linear function of exporter and importer concentration. Building on the bargaining model of firm-to-firm trade in Alviarez et al. (2025a), we demonstrate that markups rise when exporters are concentrated, reflecting oligopoly power, but fall when importers are concentrated, reflecting their countervailing oligopsony power. Which side dominates depends on three factors: the relative bargaining power of buyers and sellers, the elasticity of demand, and the elasticity of input supply.

Our second contribution is to adapt standard concentration measures to a setting where network rigidities matter. Our model defines markets based on observed trading relationships, so that firms compete only with others connected to the same partners. This makes the relevant market much narrower than the overall industry. The resulting network-based concentration measures reduce to the standard HHI only in the limit case of a single buyer or supplier. These measures remain easy to calculate—they are weighted averages of HHIs across individual buyers and suppliers—even though they rely on transaction-level price and quantity data.

Our study extends the well-known insights from textbook oligopoly theory to the case of GSCs.3 Our approach accommodates settings with heterogeneous firms and complex trading networks, while maintaining the tractability of traditional concentration analysis, making it straightforward to implement with firm-to-firm trade data.

We apply our framework to Colombian customs data covering all imports from 2011 to 2020. These records identify both importers and exporters and report product codes, quantities, and values, allowing us to compute conventional industry-wide concentration indices alongside our network-based counterparts.

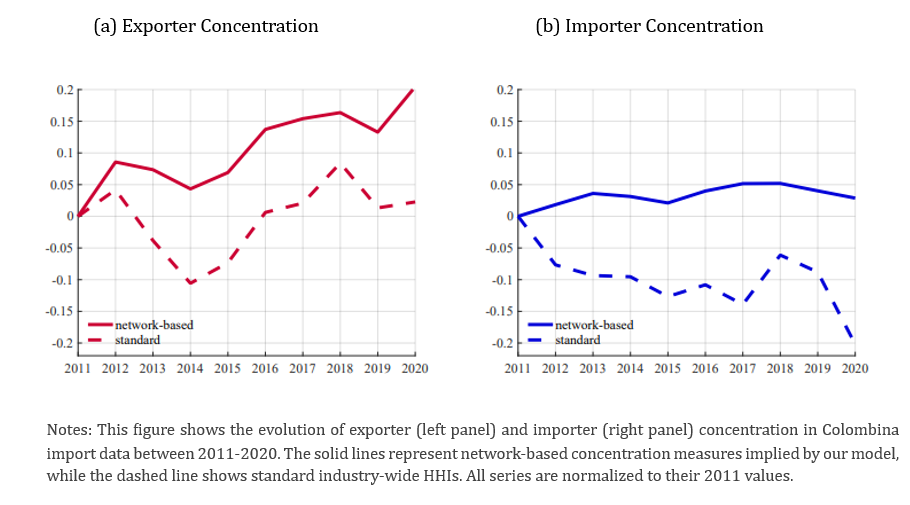

Figure 1 compares concentration trends computed using the two approaches. It shows that, between 2011 and 2020, network-based exporter concentration rose steadily, while importer concentration remained high. Industry-wide HHIs, by contrast, fluctuate or even decline over this period, giving the misleading impression that markets are becoming more competitive.

Figure 1. Concentration Trends, 2011-2020

Estimating bargaining parameters, we find that power is roughly balanced between importers and exporters. Using demand and supply elasticity estimates from the trade literature, and combined with the concentration trends in Figure 1, our framework suggests a modest but persistent increase in aggregate input markups of about 0.5 percent over the decade, driven mainly by rising exporter concentration. Stable importer concentration provided some countervailing force but was insufficient to offset the upward trend.

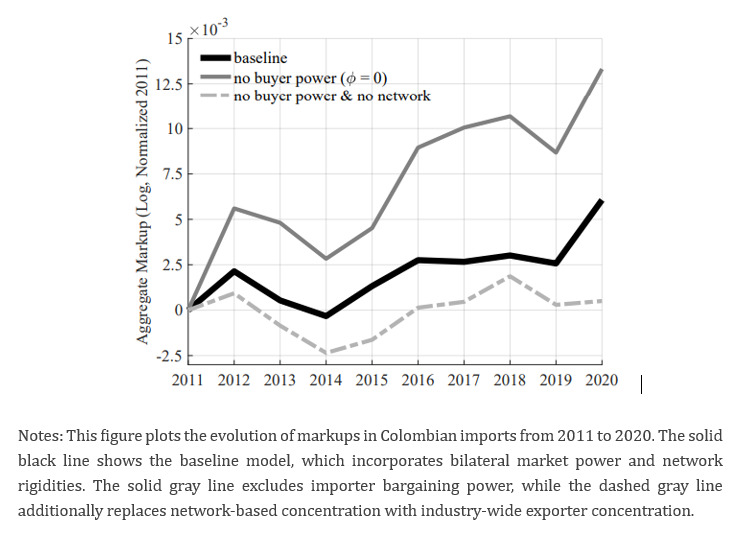

Figure 2 illustrates these dynamics. The thick black line shows our baseline estimates, while the thick grey line demonstrates that ignoring importer bargaining power more than doubles the pace of markup growth. The dashed grey line, which both ignores importer bargaining power and substitutes industry-wide concentration measures for network-based ones as in conventional concentration analysis, produces patterns largely uncorrelated with the actual trend. Together, these results highlight the importance of incorporating both buyer power and the network structure of trade when assessing markup dynamics in GSCs.

Figure 2. Markup Trends, 2011-2020

Our findings carry important implications for trade, competition, and industrial policy. Conventional concentration indices remain a cornerstone of merger review and competition cases, yet our results reveal critical shortcomings when applied to production networks and firm-to-firm trade. We show that with simple extensions, concentration analysis can be adapted to account for both sides of the market and for network rigidities, while preserving its value as a practical tool for competition policy.

Realizing the full policy potential of this approach, however, requires broader access to firm-to-firm trade data. Many countries already collect such information through customs systems, but it is rarely exploited for competition or industrial policy analysis. Comparable data for domestic transactions exist but are even less common. Expanding the use of these data would provide policymakers with timely, evidence-based indicators of supply chain concentration and pricing power. This, in turn, would improve the monitoring of global value chains and support the design of policies that promote resilience, flexibility, and fair competition.

Antràs, P. (2015). Global Production: Firms, Contracts, and Trade Structure. Princeton University Press.

Alviarez, V., Fioretti, M., Kikkawa, K., & Morlacco, M. (2025a). ‘Two-Sided Market Power in Firm-to-Firm Trade.’ NBER Working paper.

Alviarez, V., Fioretti, M., Kikkawa, K., & Morlacco, M. (2025b). ‘Concentration and Markups in International Trade.’ NBER Working paper.

Hendricks, K., & McAfee, R. P. (2010). ‘A Theory of Bilateral Oligopoly.’ Economic Inquiry, 48, 391-414.

Martin, J., Mejean, I., & Fontaine, F. (2023). ‘Relationship stickiness, international trade, and economic uncertainty,’ Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–45.

Nocke, V., & Whinston, M. D. (2022). Concentration thresholds for horizontal mergers. American Economic Review, 112(6), 1915-1948.

Syverson, C. (2019). Macroeconomics and market power: Context, implications, and open questions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(3), 23-43.

As Nocke and Whinston (2022) explain, concentration thresholds are widely used in merger review, but these measures typically assume one-sided market power.

Martin, Méjean, and Parenti (2023) show that firm-to-firm trade relationships are highly persistent.

Hendricks and McAfee (2010) is an earlier contribution linking bilateral concentration to markups in a bilateral oligopoly setting.