This policy brief is based on Foschi et al. (forthcoming), and previous versions circulated as NBER Working Paper No 33755 and Bank of Italy Working Paper No 1489. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Italy or the Eurosystem.

Abstract

Is labor migration still an important adjustment mechanism in the United States? While gross migration rates have declined over the past decades, we show that labor mobility remains responsive to local labor demand shocks. Drawing on annual data going back to the 1950s and on several instrumental variables, we demonstrate that, following an increase in regional labor demand, more than 60 percent of the ensuing rise in employment is accounted for by net immigration into that region. Young workers and populations in urban, high-income, and well-educated regions are particularly responsive to changes in labor demand. Furthermore, we find no evidence of a decline in migration elasticities over time. These results call into question the narrative that the American labor market has become increasingly rigid and underscore the importance of migration as a channel for regional adjustment. Our findings have important implications for the design of place-based policies and programs aimed at supporting economically distressed areas.

The narrative that labor mobility in the United States has structurally declined has gained traction in recent years. Lower gross migration rates and declining job-switching have raised concerns that regional labor markets may be less able to adjust to local shocks. These concerns have profound implications for the effectiveness of spatial economic policy. If workers are less likely to move, economic shocks may become more persistent, leading to rising regional disparities and calling for policies tailored towards regional business cycles rather than aggregate conditions.

In a recent paper (Foschi et al., forthcoming), we revisit the role of migration in regional adjustment. Rather than focusing solely on the level of gross migration, we ask whether labor mobility remains responsive to regional labor demand shocks. In other words, even if fewer people move overall, do they still respond to economic incentives to relocate?

To answer this question, we study how employment, unemployment, labor force participation, and population adjust in response to labor demand shocks across U.S. states, counties, and commuting zones. Using multiple instruments to capture exogenous variation in labor demand, we identify the causal effects of shocks and isolate the contribution of net migration to changes in local employment.

Our identification strategy relies on four well-established instruments for local labor demand commonly used in the literature: a Bartik-style industry composition instrument (Bartik, 1993), a military spending instrument (Nakamura and Steinsson, 2014 and Auerbach et al., 2020), a regional housing instrument (Mian and Sufi, 2014), and an import competition instrument (Autor et al., 2021). Using these instrumental variables, we capture exogenous variation in local labor demand that is plausibly unrelated to unobserved local labor supply conditions or migration preferences. Combining the results across the four instruments allows us to test the robustness of our findings across different types of shocks, geographies, and time periods.

We use data from multiple sources, including the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and the U.S. Census. This comprehensive dataset captures regional employment, population flows across regions and changes in the labor force composition back to the 1950s.

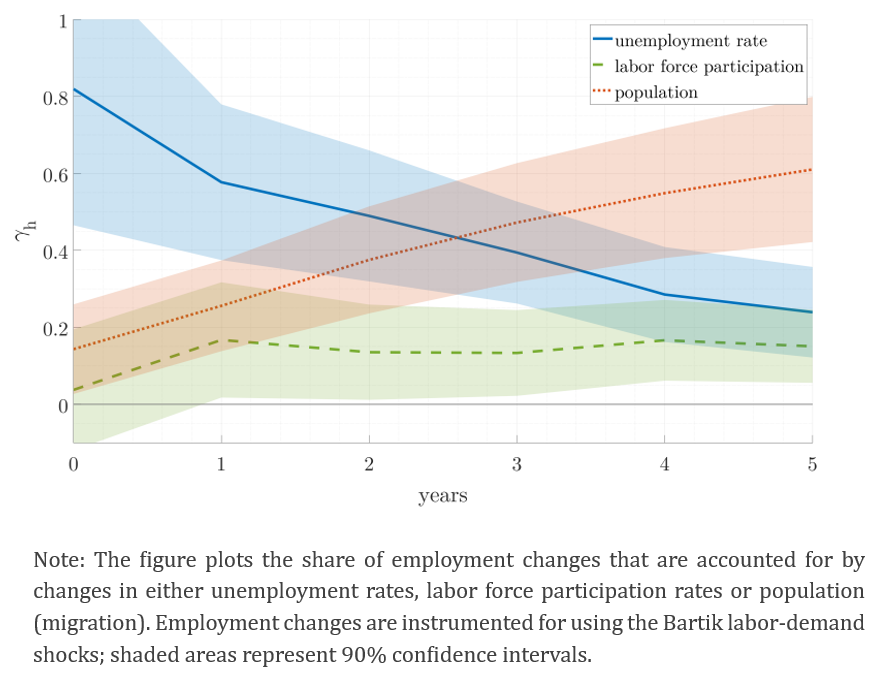

Our central finding is that net migration accounts for most long-run local employment changes following a labor demand shock. As shown in Figure 1, in the short run (1-2 years after a shock), an increase in labor demand pulls in unemployed workers. However, over longer horizons (3-5 years), net immigration becomes the dominant margin of adjustment.

Across specifications and shock types, we consistently find that approximately 50 to 70 percent of cumulative employment growth at 5-year horizons is accounted for by net migration. This is true across different geographies, including states, commuting zones, and counties. Migration remains an active and powerful force in reallocating labor to areas of opportunity.

Figure 1. Ratio between each labor market response and the employment response

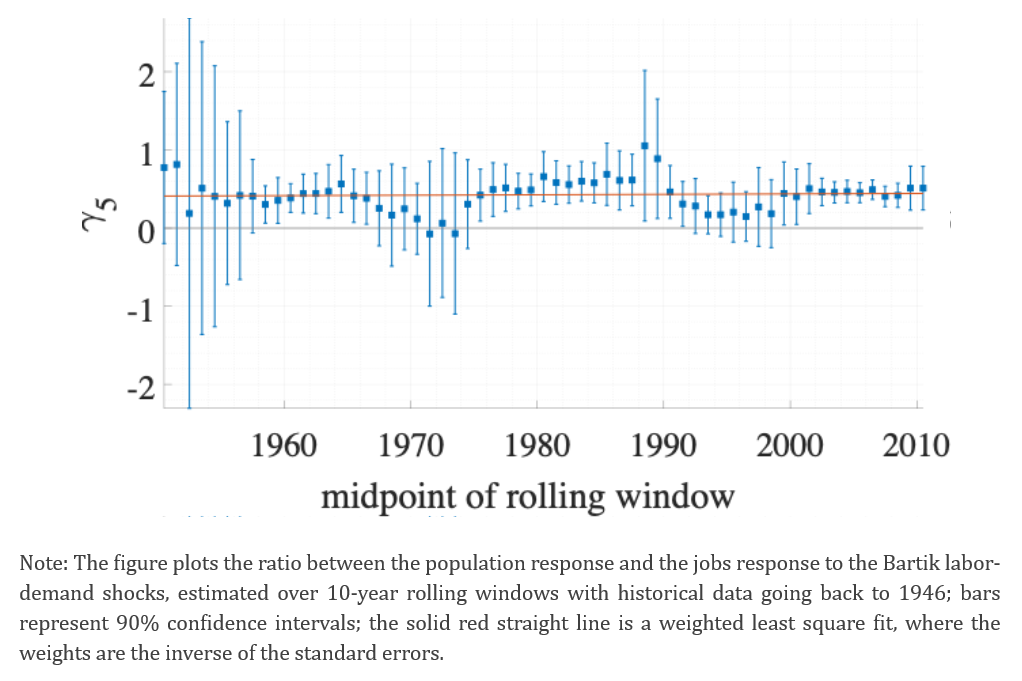

We also estimate our regressions across decades and find remarkable stability in how migration responds to labor demand shocks. The results are shown in Figure 2: the share of employment changes that is due to a change in population has not declined since the 1950s. This result challenges the view that declining gross migration implies a less responsive workforce. Instead, we show that while fewer people may be moving overall, workers still respond to differences in labor market conditions across space.

The findings also place other labor mobility research in historical context. In a seminal paper, Blanchard and Katz (1992) concluded that labor mobility is the dominant equilibrating mechanism following regional labor demand shocks. However, subsequent studies found a smaller role for mobility: for instance, Dao et al. (2017) conclude that the migration sensitivity to regional shocks has been strongly decreasing since the 1990s. While the period between 1990 and 2010 exhibited smaller migration flows, most of it can be explained by a less persistent employment response. In addition, the responsiveness of migration to regional employment differentials has since recovered and hovers around its long-run mean.

Overall, from the perspective of history, there is little evidence that the contribution of migration to labor adjustment has diminished, and policymakers should not interpret falling migration rates as evidence that labor markets are less flexible.

Figure 2. Ratio between population response and jobs response, historical data

Disaggregated analyses reveal important heterogeneity in migration responses. Younger workers – especially those aged 20 to 35 – are significantly more responsive to labor demand shocks than older ones. Moreover, migration responses are stronger in urban and high-income areas with a more educated population, relative to rural and lower-income regions with lower levels of education attainment. These differences suggest that regional characteristics mediate the effectiveness of migration as an adjustment channel.

Our findings have several implications for spatial and labor market policies. First and foremost, migration remains a vital tool for regional adjustment. Policymakers should not assume that the era of mobility is over. Policies aimed at reducing barriers to migration can enhance the effectiveness of labor market adjustments. This may include improving housing affordability in high-growth areas, reducing information frictions, and providing relocation assistance – particularly for young and low-income workers.

At the same time, this does not necessarily mean that place-based policies are unnecessary, and that policymakers can simply target the aggregate business cycle. In fact, our results also show that in-migration responds more than out-migration, suggesting that the population adjustment to regional downturns does not stem from workers leaving, but from fewer workers settling in those regions. Place-based policies may thus be warranted to help contracting labor markets by supporting the local population and attracting inflows of workers through targeted investment and job opportunities.

The decline in gross migration rates has led some to question whether labor mobility remains a meaningful force in the U.S. economy. Our research shows that this concern might be overstated. Migration continues to play a central role in reallocating labor across regions in response to economic shocks.

Net migration accounts for the majority of long-run employment responses to local labor demand shocks. Migration elasticities remain stable over time, and young workers in urban, high-income regions continue to respond strongly to job opportunities. These findings support the continued relevance of migration as a core mechanism of labor market adjustment.

As policymakers seek to design effective responses to regional disparities and economic shocks, they should recognize and support the enduring role of migration. By enhancing mobility where it is already strong and addressing constraints where it is weak, economic policies can preserve and foster the stability and dynamism of the American labor market.

Auerbach, A. J., Y. Gorodnichenko, and D. Murphy (2020). Macroeconomic Frameworks: Reconciling Evidence and Model Predictions from Demand Shocks. NBER Working Paper 26365.

Autor, D., D. Dorn, and G. H. Hanson (2021). On the Persistence of the China Shock. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Fall, 381–447.

Bartik, T. J. (1993). Who Benefits from Local Job Growth: Migrants or the Original Residents? Regional Studies 27(4), 297–311.

Blanchard, O. J. and L. F. Katz (1992). Regional Evolutions. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1992(1), 1–75.

Dao, M., D. Furceri, and P. Loungani (2017). Regional Labor Market Adjustment in the United States: Trend and Cycle. Review of Economics and Statistics 99(2), 243–257.

Foschi, A., House, C. L., Proebsting, C., & Tesar, L. L. (forthcoming). Should I Stay or Should I Go? The Response of Labor Migration to Economic Shocks. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

Mian, A. and A. Sufi (2014). What Explains the 2007–2009 Drop in Employment? Econometrica 82(6), 2197–2223.

Nakamura, E. and J. Steinsson (2014). Fiscal Stimulus in a Monetary Union: Evidence from US Regions. The American Economic Review 104(3), 753–792.