In a new paper, I shed light on how and why consumers respond to one-time payments. I administer a survey experiment in the Bundesbank Online Panel Households (BOP-HH), in which I elicit marginal propensities to consume (MPCs) out of transitory income shocks in various scenarios. Using hypothetical survey questions, I ask respondents how much they would spend out of unexpected one-time payments, exogenously varying the payment mode and the size of the payments between respondents. To explore heterogeneity in consumption responses, I use causal machine learning methods.

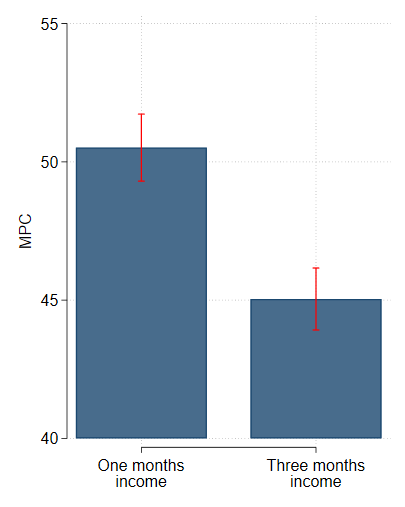

Notes: This figure shows the effect of varying the size of an income shock on individuals’ marginal propensity to consume (MPC). The bars indicate the average MPC for respondents receiving a one month’s income shock and a three months’ income shock, respectively. Solid lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

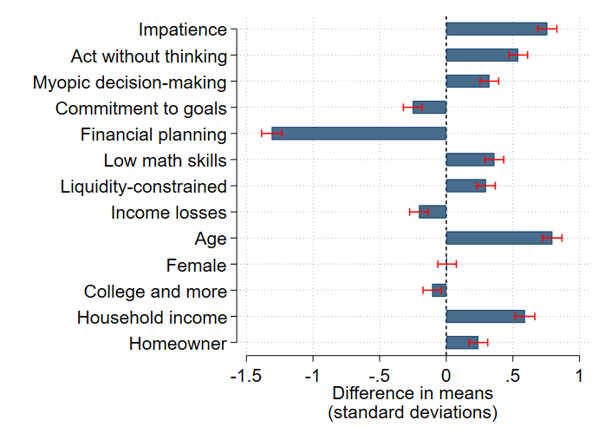

Notes: This figure compares observable characteristics between those adjusting their MPC most strongly in response to changes in the shock size and those who hardly react. The figure reports differences in means of characteristics between respondents located in the bottom and the top quartile of the shock size effect distribution. Units are standard deviations of the respective characteristic. Error bars (in red) indicate 95% confidence intervals. Behavioral and household balance sheet characteristics are elicited with the following statements to which respondents can disagree or agree with on a 7-point Likert scale: impatience – “I am generally a very patient person” (inverted scale); act without thinking – “I rarely do anything without thinking about it thoroughly” (inverted scale); myopic decision-making – “I live in the here and now and don’t really think about the future“; commitment to goals – “I actively follow through with the plans I make” (inverted scale); financial planning – “I plan major spending and investment decisions more than one year ahead“; low mathematical skills – “I have a lot of confidence in my mathematical skills” (inverted scale); liquidity-constrained – “I have put aside money for a possible emergency so that I can cover expenses for at least three months with no income” (inverted scale).

In contrast, low liquidity – as predicted by the buffer-stock model or lifecycle/permanent-income model with borrowing constraints (Carroll, 1997; Deaton, 1991) – can account for some heterogeneity in the shock size effect, while it cannot explain the differences in MPCs across payment modes.