This policy brief is based on SSRN Paper, What’s the Melting Pot Worth? Multiculturalism, House Prices and Demand. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

Would you pay a premium to live in a multicultural neighbourhood? New research from Northern Ireland finds that many homebuyers do exactly that. This finding is significant, not just because it reveals something about peoples’ preferences for their living environments, but because house prices can profoundly influence wealth inequality, community integration, and social mobility. Housing is often the largest source of wealth for households in many countries. When house prices rise, homeowners gain more wealth, potentially exacerbating inequalities between property owners and renters. Thus, understanding what drives house prices, including the cultural composition of neighbourhoods, can help policymakers shape fairer and more inclusive housing markets.

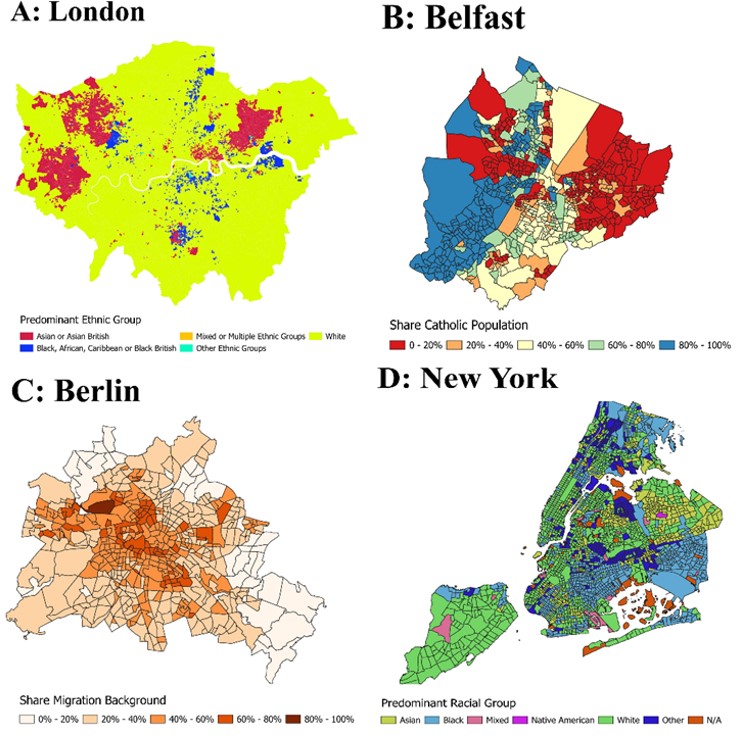

Across the world, neighborhoods’ residential composition varies sharply between segregated and multicultural. Figure 1 illustrates the high degree of variation along ethnic, racial, and religious lines in London, Belfast, Berlin, and New York.

Figure 1. Neighbourhood Composition Examples

Notes: Panel A maps London’s predominant ethnic group across Lower Super Output Areas using the 2021 UK Census (Office for National Statistics). Panel B depicts the percentage of Catholics in Belfast’s Data Zones from the 2021 Northern Ireland Census (NISRA). Panel C presents the share of residents with a migration background in Berlin’s LOR-Planungsräume based on register statistics as of 31 December 2024 (Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg). Panel D shows the predominant racial group in each 2020 census tract of New York City using the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020 Redistricting (P.L. 94-171) data.

The relationship between cultural diversity and house prices is complex. Historically, research suggested people often prefer living near others like themselves, a phenomenon known as homophily. In more culturally diverse areas, differences in cultural attitudes and norms can lead to lower levels of social cohesion and cooperation, or even – in rare cases – competition and conflict (Alesina & La Ferrara, 2000, 2005). These factors might reduce the desirability of more diverse neighbourhoods, exerting a negative effect on house prices.

However, an alternative perspective holds that diversity can lead to fruitful exchanges of different viewpoints and ideas improving human capital accumulation and learning in culturally mixed environments (Alesina et al., 2016, Chetty et al., 2016). Such positive spillovers would raise the attractiveness of diverse neighbourhoods and push up house prices.

To further investigate these competing theories, researchers from the Universities of Augsburg, Birmingham, Durham, Jena, and Halle Institute for Economic Research looked closely at Northern Ireland, a part of the UK that has historically experienced deep divisions between Catholic and Protestant communities. Specifically, Cho et al. (2025) found an ideal setting to causally investigate the effects of cultural diversity on house prices, which the existing literature found difficult to establish.

The roots of Northern Ireland’s contemporary neighbourhoods go back to the early 1600s when British colonization of Ulster created lasting cultural divisions between a predominantly Catholic native population and Protestant settlers transplanted from England and Scottland.

Due to the difficulty of administering the colonialization of the area from London, many estates were settled in a haphazard, quasi-random fashion, leading to some areas becoming more mixed, while others became almost exclusively Protestant or remained predominantly Catholic.

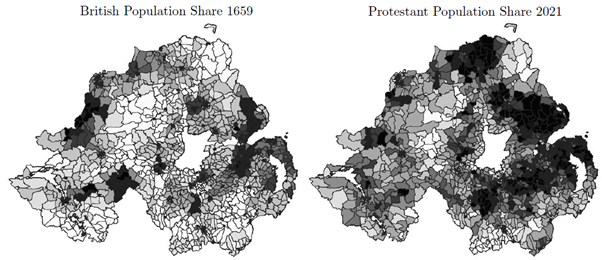

The fact that we have any quantitative evidence of this process is due to the hard work of Sir William Petty (1623 – 1687), who lead the first granular survey of the land and population of Ireland, known as Petty’s or Pender’s Census of Ireland, which was completed between 1654 and 1659. Using the detailed population information contained in the archival census, the researchers found a high degree of persistence in the cultural makeup of different parts of Northern Ireland, the details of which can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Historical and Contemporary Cultural Composition in Northern Ireland

Notes: Share of British settlers in the 1659 Census of Ireland (left); and share of Protestant population in the 2021 NI Census (right). Darker shading indicates a higher share.

Areas with a higher share of British settlers in 1659, consistently exhibit a higher share of Protestant population in the most recent census of Northern Ireland. Despite a gap of nearly 400 years, the events of the colonialization of Ulster, still affect the cultural makeup of communities to this day. This unique historical accident allowed the researchers to measure how diversity, rather than associated socioeconomic factors, affects house prices in the 21st century.

The researchers use data on contemporary house sales (2021-2025) in conjunction with statistical techniques to isolate the causal effect of diversity on house prices. They discover a clear “diversity premium”: on average, properties in culturally diverse neighbourhoods sell for nearly 10% more than those in culturally segregated areas.

Why might people value multicultural neighbourhoods more highly? One key reason is that these areas attract a broader spectrum of potential buyers. When a neighbourhood appeals to a broader section of society, homes become easier to sell, reducing the risk associated with property investment. Moreover, multicultural neighbourhoods often boast better schools, public services, and opportunities for social interaction, indicators of the positive spillovers of cultural diversity.

A key question related to the diversity premium is to what extent it reflects discrimination and intra-cultural buyer-seller networks. Many studies (Wong, 2013; Agarwal et al., 2019) find that sellers are often willing to give a considerable discount to potential buyers from a similar ethnic or cultural background. In diverse neighbourhoods, where more inter-cultural transactions occur, higher prices might therefore reflect discrimination rather than true desirability.

To investigate this the researchers, turn to property title deeds which allows them to study the ownership history of different houses. They identify the likely cultural background of the transacting parties and analyse if there are significant differences in transactions involving both Catholics and Protestants.

They find that as hypothesised, there are more inter-cultural transactions in more diverse neighbourhoods, supporting the idea that these areas attract more buyers from both cultural communities. Further they find no evidence of a discriminatory price premium in inter-cultural transactions. These additional findings suggest that the diversity premium broadly reflects the increased willingness of both Catholic and Protestant buyers to purchase properties in more diverse neighbourhoods rather than any form of price discrimination.

While the diversity premium tells a broadly positive story about the role of cultural diversity and integration in Northern Ireland, these findings have further important implications for economic and social inequality. If multicultural neighbourhoods command higher house prices, homeowners in these areas gain disproportionately from rising property values, amplifying wealth differences between those who own property in diverse neighbourhoods and those who do not.

Rising house-price differentials between mixed and segregated areas might mean that those who own properties in less diverse neighbourhoods become increasingly shut out of vibrant, diverse neighbourhoods. This might be particularly problematic since diverse areas are associated with better access to opportunities for learning, working and investing. In the long run this might hurt social mobility and create a sense of alienation amongst those that are priced out of the opportunities that diversity can bring, entrenching the divisions society has worked so hard to overcome.

However, there is also a positive side. The attractiveness of multicultural areas suggests that encouraging diversity could be a powerful policy tool to regenerate neighbourhoods, improve public services, and foster social integration. Targeted investments in promoting diversity, through schools, community projects, or urban planning, might help lift less desirable neighbourhoods economically and socially, reducing overall inequality and creating sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

Agarwal, Sumit, Hyun-Soo Choi, Jia He, and Tien Foo Sing. “Matching in housing markets: The role of ethnic social networks.” The Review of Financial Studies 32, no. 10 (2019): 3958-4004.

Alesina, Alberto, and Eliana La Ferrara. “Participation in heterogeneous communities.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115, no. 3 (2000): 847-904.

Alesina, Alberto, and Eliana La Ferrara. “Ethnic diversity and economic performance.” Journal of Economic Literature 43, no. 3 (2005): 762-800.

Alesina, Alberto, Johann Harnoss, and Hillel Rapoport. “Birthplace diversity and economic prosperity.” Journal of Economic Growth 21 (2016): 101-138.

Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz. “The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment.” American Economic Review 106, no. 4 (2016): 855-902.

Cho, Rachel, Hisham Farag, Christoph Görtz, Danny McGowan, Huyen Nguyen and Max Schröder. “What’s the Melting Pot Worth? Multiculturalism and House Prices.” IWH Discussion Papers No. 11 (2025).

Wong, Maisy. “Estimating ethnic preferences using ethnic housing quotas in Singapore.” Review of Economic Studies 80, no. 3 (2013): 1178-1214.