We would like to thank the co-leads of the Strategy Review Workstream on Employment (Claus Brand, Guenter Coenen, Reamonn Lydon, Meri Obstbaum and David Sondermann), and Jelena Zivanovic. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect views of the Bank of Portugal, the Central Bank of Ireland, or the European Central Bank. Any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the authors.

A particular feature of the euro area is that monetary policy is conducted based on area-wide considerations, while labour market institutions differ between countries in the union. These differences in labour market institutions between countries of the monetary union can give rise to heterogeneous responses to shocks across countries within the union, even when the shocks hit all monetary union regions symmetrically. Moreover, different households within an economy can be affected to a different degree by a shock. These considerations play some role in monetary policy frameworks, as can be seen from the fact that the ECB in its last Strategy Review considered the interaction of monetary policy and labour markets (Brand et al., 2021).

We first compute responses to a common expansionary and inflationary demand shock, which increases inflation and reduces unemployment, and therefore does not create a direct trade-off between inflation and unemployment stabilisation. We next compute the responses to a contractionary and inflationary supply shock, which increases both inflation and unemployment and therefore implies a trade-off for a central bank between inflation and unemployment stabilisation.

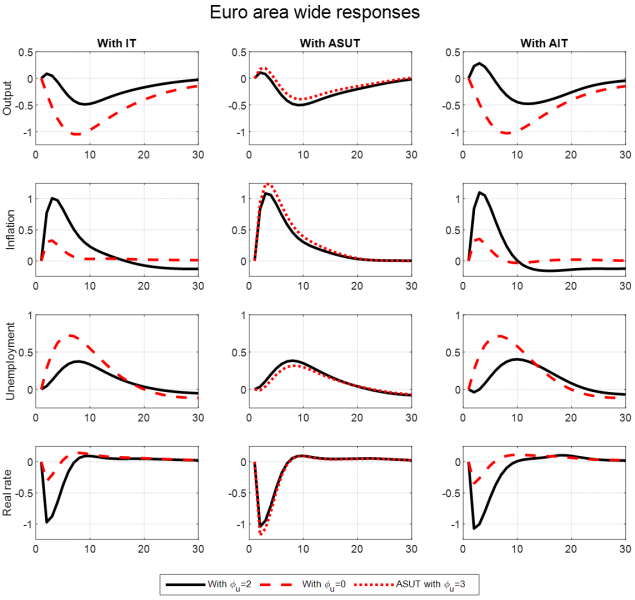

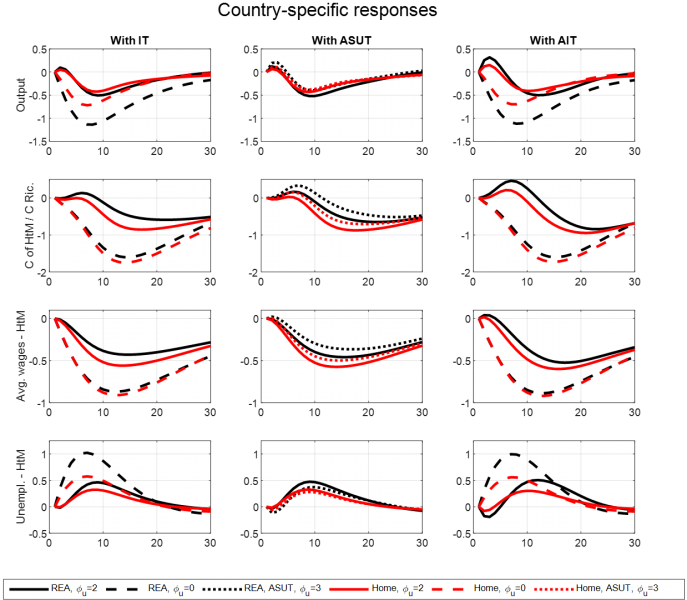

For the expansionary demand shock, we consider a combination of a preference shock and an investment technology shock, symmetrically in both euro area regions. Shock sizes are standardised to achieve a 1 p.p. maximum increase in inflation (annualised) under the benchmark IT rule with a positive weight on unemployment, and this size of shocks is kept fixed across simulations with different monetary policy rules. Figure 1 shows the euro-area-wide variables for the three interest rate rules, one in each column and for different weights placed on unemployment. The full black line shows the case when the central bank responds to the unemployment rate and the dashed red line shows the case where the central bank does not respond to unemployment. For the ASUT rule the case where the weight on unemployment is zero always corresponds to the strict inflation targeting rule, i.e., to dashed red lines in the leftmost column of the figure.

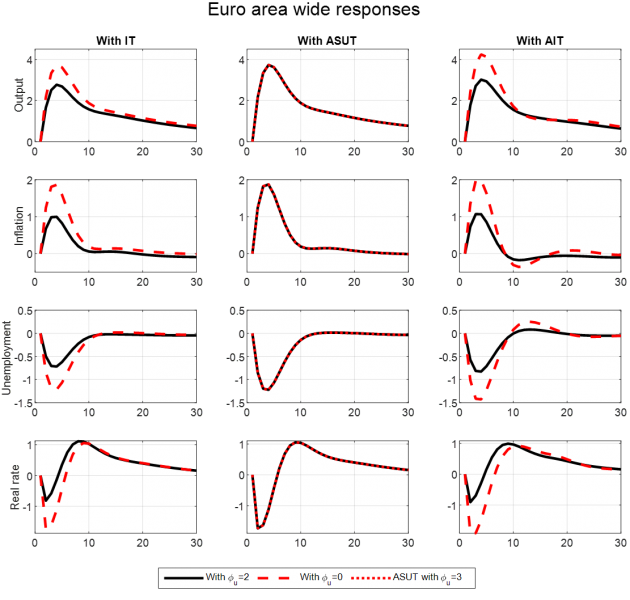

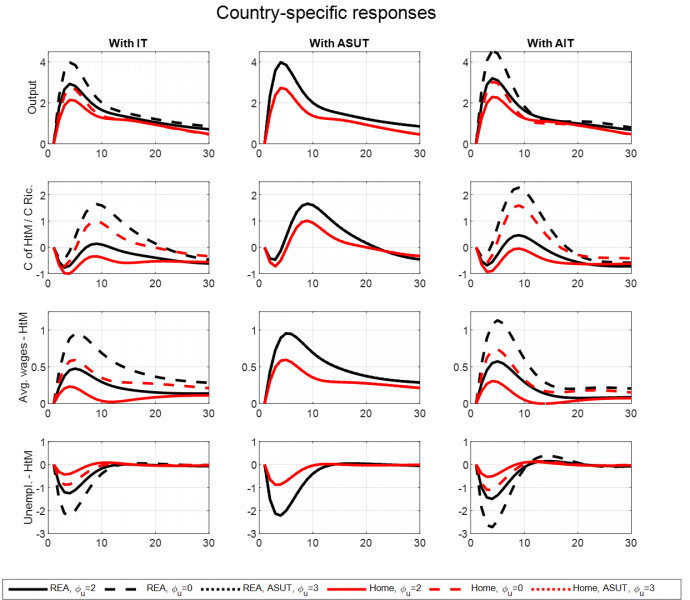

We now investigate the performance of monetary policy rules under the shock scenario that induces a trade-off between stabilizing inflation and unemployment. To achieve this, we simulate an asymmetric and equal increase in markups in tradable and non-tradable sectors in both blocs of the euro area. As before, the size of the shock is calibrated to achieve a 1 p.p. maximum increase in the euro-area-wide inflation under the benchmark rule and the size of the shock is kept the same across policy rules.

Figure 3 shows the euro area-wide outcomes. The supply shock generates an increase in inflation and a negative impact on economic activity. As in the previous case, the fluctuations in (un)employment, aggregate demand and its components are stronger if the central bank pays no attention to unemployment, while in this case inflation shows a much milder increase. Compared to the other two rules, AIT tends to attenuate or even neutralise the negative real impact of the shock in the first few quarters when the central bank reacts to unemployment, mainly because this rule stipulates a slower increase in the nominal rate, which results in a stronger drop in the real interest rate and hence an increase in Ricardian households’ consumption in the short run. Because these households represent 75% of all households, they have a strong influence on aggregate consumption.